A Sense of Doubt blog post #2038 - What is poetry

I want to make a video for my current creative writing class on "what is poetry." This is my planning stage, accumulating articles that speak to this idea.

Funny, though, I was teaching creative writing last semester, too, and I wanted t make this video and never managed to do so.

I kept delaying the video because I thought that I had to take it on myself to write something to explain poetry rather than just using the Internet to see what others, far more learned and articulate than I, have written on this subject.

I will keep my comments simple as I am still in "break" mode.

As for poetry, I know it when I see it. A poem can be many things, and so definitions are slippery. I like the Ferlinghetti idea below as well as the ideas of Wordsworth, Dickinson, and Thomas in the opening paragraph of the first article.

A poem does not have to rhyme. It does not need to follow a set form, though it should be artful and have it own internal logic and structure.

And so, I know it when I see it.

Also, to be a GOOD poem, it must start strong and have a killer last line. That's my own subjective feeling of what I like best. It really should have many other elements (figurative language), but my favorite poems start strong and have a killer last line.

On to the definitions.

Thanks for tuning in.

On that, this is a poem:

Mary Oliver - "Wild Geese"

Wild Geese

by Mary Oliver

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

· · · · · ·

Mary Oliver, born in 1935 in Cleveland, Ohio, is part of the Modern American Poetry genre. A post-Romantic naturalist, Oliver has won many awards (Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award...). She has published ten collections of poems and is a professor at Bennington College in Vermont. You can buy her books at your local bookstore, through Booksense.com. Wild Geese was first published in Dream Work, Atlantic Monthly Press, 1986, © 1986 Mary Oliver.

Published under the provision of U.S. Code, Title 17, section 107.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Poetry_is_the_shadow_cast_by_our_streetlight_imaginations_by_Lawrence_Ferlinghetti_-_Jack_Kerouac_Alley-9a1d0634117645d2af7f7ac6208dc45e.jpg)

https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-poetry-852737

Updated July 19, 2019

There

are as many definitions of poetry as there are poets. William Wordsworth

defined poetry as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings."

Emily Dickinson said, "If I read a book and it makes my body so cold no

fire ever can warm me, I know that is poetry." Dylan Thomas defined poetry

this way: "Poetry is what makes me laugh or cry or yawn, what makes my

toenails twinkle, what makes me want to do this or that or nothing."

Poetry

is a lot of things to a lot of people. Homer's epic, "The Odyssey,"

described the wanderings of the adventurer, Odysseus, and has been called the

greatest story ever told. During the English Renaissance, dramatic poets such

as John Milton, Christopher Marlowe, and of course, William Shakespeare gave us

enough words to fill textbooks, lecture halls, and universities. Poems from the

Romantic period include Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's "Faust" (1808),

Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Kubla Khan" (1816), and John Keats'

"Ode on a Grecian Urn" (1819).

Shall

we go on? Because in order to do so, we would have to continue through

19th-century Japanese poetry, early Americans that include Emily Dickinson and

T.S. Eliot, postmodernism, experimentalists, form versus free verse, slam, and

so on.

What Defines Poetry?

Perhaps

the characteristic most central to the definition of poetry is its

unwillingness to be defined, labeled, or nailed down. Poetry is the chiseled

marble of language. It is a paint-spattered canvas, but the poet uses words

instead of paint, and the canvas is you. Poetic definitions of poetry kind of

spiral in on themselves, however, like a dog eating itself from the tail up.

Let's get nitty. Let's, in fact, get gritty. We can likely render an accessible

definition of poetry by simply looking at its form and its purpose.

One of

the most definable characteristics of the poetic form is the economy of

language. Poets are miserly and unrelentingly critical in the way they dole out

words. Carefully selecting words for conciseness and clarity is standard, even

for writers of prose. However, poets go well beyond this, considering a word's

emotive qualities, its backstory, its musical value, its double- or

triple-entendres, and even its spatial relationship on the page. The poet,

through innovation in both word choice and form, seemingly rends significance

from thin air.

One may

use prose to

narrate, describe, argue, or define. There are equally numerous reasons

for writing poetry.

But poetry, unlike prose, often has an underlying and overarching purpose that

goes beyond the literal. Poetry is evocative. It typically provokes in the

reader an intense emotion: joy, sorrow, anger, catharsis, love, etc. Poetry has

the ability to surprise the reader with an "Ah-ha!" experience and to

give revelation, insight, and further understanding of elemental truth and

beauty. Like Keats said: "Beauty is truth. Truth, beauty. That is all ye

know on Earth and all ye need to know."

How's

that? Do we have a definition yet? Let's sum it up like this: Poetry is

artistically rendering words in such a way as to evoke intense emotion or an

"ah-ha!" experience from the reader, being economical with language

and often writing in a set form. Boiling it

down like that doesn't quite satisfy all the nuances, the rich history, and the

work that goes into selecting each word, phrase, metaphor, and punctuation mark to

craft a written piece of poetry, but it's a start.

It's

difficult to shackle poetry with definitions. Poetry is not old, frail, and

cerebral. Poetry is stronger and fresher than you think. Poetry is imagination

and will break those chains faster than you can say "Harlem

Renaissance."

To

borrow a phrase, poetry is a riddle wrapped in an enigma swathed in a cardigan

sweater... or something like that. An ever-evolving genre, it will shirk

definitions at every turn. That continual evolution keeps it alive. Its

inherent challenges to doing it well and its ability to get at the core of

emotion or learning keep people writing it. The writers are just the first ones

to have the ah-ha moments as they're putting the words on the page (and

revising them).

Rhythm and Rhyme

If

poetry as a genre defies easy description, we can at least look at labels of

different kinds of forms. Writing in form doesn't just mean that you need to

pick the right words but that you need to have correct rhythm (prescribed

stressed and unstressed syllables), follow a rhyming scheme (alternate lines

rhyme or consecutive lines rhyme), or use a refrain or repeated line.

Rhythm.

You may have heard about writing in iambic

pentameter, but don't be intimidated by the jargon. Iambic just

means that there is an unstressed syllable that comes before a stressed one. It

has a "clip-clop," horse gallop feel. One stressed and one unstressed

syllable makes one "foot," of the rhythm, or meter, and five in a row

makes up pentameter. For example, look at this

line from Shakespeare's "Romeo & Juliet," which has the stressed

syllables bolded:

"But, soft! What light through yonder window breaks?"

Shakespeare was a master at iambic pentameter.

Rhyme

scheme. Many set forms follow a particular pattern

to their rhyming. When analyzing a rhyme scheme, lines are labeled with letters

to note what ending of each rhymes with which other. Take this stanza

from Edgar Allen Poe's

ballad "Annabel Lee:"

It was

many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

The

first and third lines rhyme, and the second, fourth, and sixth lines rhyme,

which means it has an a-b-a-b-c-b rhyme scheme, as "thought" does not

rhyme with any of the other lines. When lines rhyme and they're next to each

other, they're called a rhyming couplet. Three in a row is called a rhyming triplet. This

example does not have a rhyming couplet or triplet because the rhymes are on

alternating lines.

Poetic Forms

Even

young schoolchildren are familiar with poetry such as the ballad form

(alternating rhyme scheme), the haiku (three lines

made up of five syllables, seven syllables, and five syllables), and even the

limerick — yes, that's a poetic form in that it has a rhythm and rhyme scheme.

It might not be literary, but it is poetry.

Blank verse poems are written in an iambic format, but they don't carry a rhyme scheme. If you want to try your hand at challenging, complex forms, those include the sonnet (Shakespeare's bread and butter), villanelle (such as Dylan Thomas's "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night."), and sestina, which rotates line-ending words in a specific pattern among its six stanzas. For terza rima, check out translations of Dante Alighieri's "The Divine Comedy," which follows this rhyme scheme: aba, bcb, cdc, ded in iambic pentameter.

Free

verse doesn't have any rhythm or rhyme scheme, though its words still need to

be written economically. Words that start and end lines still have particular

weight, even if they don't rhyme or have to follow any particular metering

pattern.

The more poetry you read, the better you'll be able to internalize the form and invent within it. When the form seems second nature, then the words will flow from your imagination to fill it more effectively than when you're first learning the form.

Masters in Their Field

The

list of masterful poets is long. To find what kinds you like, read a wide

variety of poetry, including those already mentioned here. Include poets from

around the world and all through time, from the "Tao Te Ching" to

Robert Bly and his translations (Pablo Neruda, Rumi, and many others). Read

Langston Hughes to Robert Frost. Walt Whitman to Maya

Angelou. Sappho to Oscar Wilde. The list goes on and on. With poets of all

nationalities and backgrounds putting out work today, your study never really

has to end, especially when you find someone's work that sends electricity up

your spine.

Source

Flanagan,

Mark. "What is Poetry?" Run Spot Run, April 25, 2015.

Grein,

Dusty. "How to Write a Sestina (with Examples and Diagrams)." The

Society of Classical Poets, December 14, 2016.

Shakespeare,

William. "Romeo and Juliet." Paperback, CreateSpace Independent

Publishing Platform, June 25, 2015.

What Is Poetry?

by Dan Rifenburgh

I.

We may feel we know what a thing is, but have trouble defining it. That holds as true for poetry as it does for, say, love or electricity. The American poet Emily Dickinson, though shrinking from offering a definition of poetry, once confided in a letter, "If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry." A well-known British poet, A.E. Housman, could identify poetry through a similar response. He said that he had to keep a close watch over his thoughts when he was shaving in the morning, for if a line of poetry strayed into his memory, a shiver raced down his spine and his skin would bristle so that his razor ceased to act. What is this thing that can so physically affect some persons?

One poet called a poem "a thought, caught in the act of dawning." Another said a poem is a means of bringing the wind in the grasses into the house. Yet another stated, even more enigmatically: "Poetry is a pheasant disappearing in the brush." It is just like poets, of course, to talk this way: poetically. It often seems they refrain from saying a thing straight if they can give it a little twist. Such tendencies make you want to lay hands on a good dictionary, where the facts are. The trouble with this approach is, most dictionary definitions of poetry are so dry, limiting, vague, or otherwise unsatisfactory, they eventually send you back to beating the bushes for that elusive, beautiful pheasant you once glimpsed. It's certainly not there in the dictionary. Even so, it is possible to describe the general elements of poetry and to at least indicate the power, range, and magic of this ancient, ever-renewing art form.

Like other forms of literature, poetry may seek to tell a story, enact a drama, convey ideas, offer vivid, unique description or express our inward spiritual, emotional, or psychological states. Yet, poetry pays particularly close attention to words themselves: their sounds, textures, patterns, and meanings. It takes special pleasure in focusing on the verbal music inherent in language.

When we hear a poem, we may recognize certain patterns, such as a regular beat, a rising rhythm, or a series of rhymes. When we see a poem printed on a page, we might notice another kind of pattern that cues us we are not looking at standard prose: those ragged right-hand margins, indicating the lines must stop there and nowhere else. Whether we hear a poem read aloud or read it on a page, it ought to be clear we are experiencing a special patterned arrangement of language, differing from ordinary speech or prose writing.

This formal patterning, considered aside, for a moment, from poetry's higher aims or its subject matter, has long been one of the chief identifying hallmarks of poetry. Roughly speaking, the devices by which poets achieve these patterned arrangements of language are called the elements of verse. The word "verse" comes to us from the Latin versus, a "turning," and denotes the turning from the end of one line to the beginning of the next line. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, as for us today, the line was the basic unit of poetry, just as the sentence is the basic unit of prose. Greek and Roman lines were regular in their structure and could be classified and analyzed according to their component elements, the poetic feet in each line, which gives the line's meter. Over time, verse has come to mean poetic composition in regular meter, or metrical composition. Here is an example of English poetry written in a regular meter:

Like as the waves make toward the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

To a person acquainted with verse, the predominant meter here will be readily seen as iambic pentameter, the standard meter of English literary poetry. An iamb is a metrical foot consisting of two syllables. The first syllable is unstressed and the second syllable receives a stress, as in "ta-DA." There are five of these feet in each line, which is why it is called "pentameter."

Below are two of these lines divided by stroke marks into their component metrical feet (iambs) and the stressed syllable in each foot is capitalized:

Each CHANG/ing PLACE/ with THAT/ which GOES/ beFORE

In SE/quent TOIL/ all FOR/wards DO/ conTEND.

Not every line of the four lines first quoted above is a perfect iambic pentameter line. Good poets change their meters occasionally to provide variety or for other reasons, but since the predominant meter is iambic pentameter, we can say that is the meter of the poem. Having established the meter, we may also note the end words of each line rhyme in an alternating scheme we can denote as "A-B-A-B." Those end words are "shore," "end," "before" and "contend." So, we have an example here of rhymed iambic pentameter, a charming snippet of metrical verse from the pen of William Shakespeare.

Verse is poetic composition in regular meter, whether rhymed or not. (If unrhymed, it is called blank verse, as in Milton's Paradise Lost or Shakespeare's dramatic verse.) The exception to this is free verse, which abandons metrical regularity altogether. Yet it, too, "turns" on the basic unit of the line and may rightfully be called verse. The long, rolling, repetitive lines of American poet Walt Whitman and the passionate Hebrew psalms found in the Holy Bible are well-known older examples of free verse. Free verse has grown in popularity since the early twentieth century and has now pretty well "swept the field," as poet Stanley Kunitz observed. The majority of poets today choose to work in free verse, though there are many fine poets still working in meter.

Having loosely established what verse is, it should now be emphasized that verse is not what we mean by the word "poetry." Devices such as rhythm, rhyme, alliteration, meter, and regular line length are elements of verse which aid poets in producing patterned arrangements of language called "poems," yet, supplemental to these, certain qualities of imagination, of emotion, and of language itself must be added before we can properly call a piece of writing by the name of "poetry." Poetry is considered a higher thing than mere verse, and for good reasons. This is an important point, to which we'll want shortly to return, but let's consider verse and its patternings a little farther.

It is surprising to some people to learn that more than ninety percent of the poems in any standard anthology of English poetry are written in formally structured, highly patterned metrical verse. Similarly high percentages would obtain for anthologies of the poetry of most other languages, including Greek, German, French, Latin, Russian and Spanish. Why?

Formal patterns seem to help preserve and hold the ideas, emotional power, and verbal energy of poetry as a bottle holds wine. Devices such as repetition, alliteration, rhythm, rhyme, and meter also greatly aid the human mind in memorizing poetry. This was vital to poetry's existence before the invention of writing. Homer's vast epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, were oral compositions committed to and transmitted by human memory before they were eventually written down. Much of early Greek poetry was transmitted by rhapsodes, or human reciters. The same was true of the lengthy historical narratives composed and memorized by the bards of Ireland and Wales, who were the official repositories of their peoples' histories. This same phenomenon appears in cultures all around the globe.

There is a very old saying, "Art is long; life is short." Poetic art has a better chance of becoming long-lasting art when it takes advantage of the devices of verse which serve to pattern language. One American poet once said that a poem is "a time machine" made out of words, by means of which people in the past may speak to us and we may speak to people in the past, present, and future. It is a famous conceit of poets that they have the ability to "immortalize" in verse their lovers, for instance. Consider this concluding couplet from one of Shakespeare's sonnets:

So long as men can breath or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The urge to defeat death and escape the ravages of time is a basic motive underlying the creation of all art. If one wishes to fashion immortal verse, to construct, as it were, "a time machine," one would want one's words to bememorable, and that is part of the job description of the several devices of verse: to aid in giving a poem memorability.

Sooner or later it dawns on most poets that, happily, they have entered a vast, ongoing, and varied conversation that spans the centuries. Through their acts of creative composition they can join the great poet John Donne in saying, "Death, be not proud." Every poet has at least the hope that his or her work will survive an individual life's span, and art is one of the few tools we have to kick a little sand in the eye of the Grim Reaper. Notice that in this particular bid for eternal fame, Shakespeare chose a rhymed iambic pentameter couplet to preserve his living words. Patterned arrangements of language gain in memorability and offer a leg up in the quest for that immortality poetic art seeks for itself.

II.

Aside from the charm, musicality, and memorability verse lends to poetry, we expect great poetry to display qualities of invention and imagination. The word "poet" means, in Greek, "maker." To the early Greeks the poet was a creator with singular gifts of inspiration, invention, and composition. The poet invented fables, fictions, myths, and stories that conveyed deep truths about the world and human life. This ability of the poet to create something new and interesting was remarked upon by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night's Dream:

The poet's eye in a fine frenzy rolling

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven,

And as imagination bodies forth

The form of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Of course, the poet doesn't create out of "nothing" and make a world out of whole cloth. His compositions, to have any meaning, must have some relation to the world of human beings and to nature. Given that relation, however, the poet enjoys a great deal of creative freedom. As Sir Phillip Sydney wrote in "An Apology For Poetry,"

Only the poet . . . lifted up with the vigor of his own invention . . . goeth

hand in hand with nature, not enclosed within the narrow warrant of her

gifts, but freely ranging within the zodiac of his own wit.

The English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge considered the faculty of imagination to be a repetition in our finite minds of the immeasurable creativity within the imagination of the infinite "I Am," or, God. If poets are human exemplars of this divine creative quality, it is little wonder the philosopher Plato stated, "A poet is a light and winged thing, and holy." One such poet was the American poet Emily Dickinson. A recluse in life, she found an immortal voice in short, powerful verses, such as her 1862 poem, "This Is My Letter to the World":

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me--

The simple News that Nature told--

With tender MajestyHer Message is committed

To Hands I cannot see--

For love of Her--Sweet--countrymen

Judge tenderly--of Me

While many great poets such as Dickinson best express themselves in brief lyrical works, others give us more fully sustained displays of the power of invention: the Italian Dante Alligheri takes us on an incredible tour of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise in his Divine Comedy; John Milton gives us the rebellious angel Lucifer fighting eternal war against God, with all humanity as both prize and witness, inParadise Lost; Homer tells of the long homeward journey of a veteran after the Trojan War in The Odyssey, with fascinating episodes of shipwreck, survival, and suspense, building to the final homecoming of Ulysses to his wife and child on the island kingdom of Ithaca, where one final battle awaits him.

We may note that these stories, legends, and fictions are never told in sweeping, hollow generalities, but the poet always hones in on specific, tactile details, pungent with sensuous imagery, all of which paint startlingly realistic portraits through the use of vivid, accurate language.

Along with making use of lively detail, the ability of the poet to notice correspondences, similarities, and analogies and to employ these in constructing fresh and original metaphors lies at the heart of great poetry, and is part of its imaginative sweep. The often sensuous, figurative language of simile and metaphor seems to appeal greatly to the human mind. Consider the opening stanza and fifth stanza of "First Snow in Alsace," by World War II veteran and Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Wilbur:

The snow came down last night like moths

Burned on the moon; it fell till dawn

Covered the town with simple cloths.

* * *

You think: beyond the town a mile

Or two, this snowfall fills the eyes

Of soldiers dead a little while.

Here the magical beauty of the first snow is described against the backdrop of war, a contrast made more powerful by the simile comparing of falling snowflakes to dead moths. (Wilbur reads this poem on the Operation Homecoming CD.)

Similarly, the seventeenth-century Welsh poet Henry Vaughan formulates a luminous simile and extends it at some length in "The World." Here is the art of poetry at the top of its form, as revelation through metaphor of profound spiritual vision.

I saw eternity the other night

Like a great ring of pure and endless light,

All calm as it was bright

And round beneath it, time, in hours, days, years,

Driven by the spheres,

Like a vast shadow moved, in which the world

And all her train were hurled.

We can be reasonably sure that we have risen above mere verse at this point and shifted into the higher plane of full-bodied poetry, where qualities of imagination, vision, and invention are seen coming clearly into play. And yet, we have still not touched on one final, vital ingredient of great poetry.

III.

In addition to qualities of memorability, musicality, imagination, and invention, we expect poetry to touch us at an emotional level. Take the passion out of poetry, and we are left with something dry and rather ridiculous. "A poem begins with a lump in the throat, a homesickness or love-sickness," said Robert Frost. "It is a reaching out toward expression; an effort to find fulfillment." The great English poet William Wordsworth said, "Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." According to Wordsworth, the urge to write begins with a person's strong feelings. This is what impels human beings to break from silence into utterance.

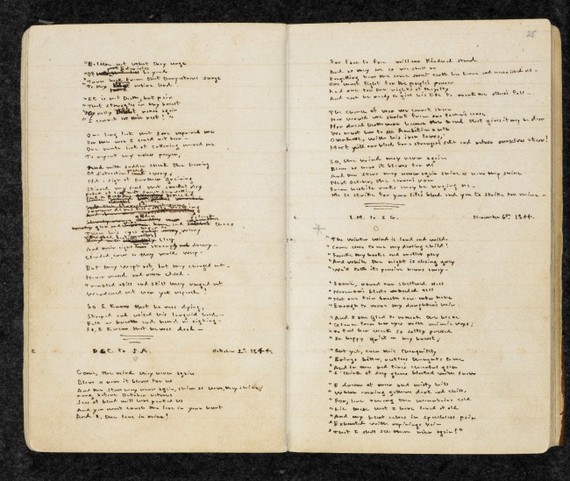

A poem may be admirable because it grants us an insight into some truth about ourselves or the universe we inhabit. It may engage in abstruse aesthetic projects or metaphysical speculations that are intellectually quite sophisticated. Conversely, it may be simple and direct, and those are often the most powerful kinds of poems. Think, for instance, of how we might savor a sad blues song. One doesn't need advanced degrees to appreciate a line like, "I woke up this morning, blues all around my bed," or "Oh, I hate to see that evenin' sun go down." Lines like these come from the heart and are meant to touch other hearts. Consider this anonymously written fragment of English poetry from the early sixteenth century:

Western wind, when wilt thou blow

That the small rain down can rain?

Christ, that my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

We don't know the full situation of the speaker here, but there is no mistaking the heartfelt longing for home in the voice. It is that unmistakable human passion that has caused this scrap of poetry to live for more than five hundred years.

There is a fine line between the poem which makes an authentic claim upon the core of our emotional being and the poem which seems to wish to manipulate us, to play insincerely, or ineptly, upon our heartstrings. When dealing with emotionally charged matter, the poet faces the danger of lapsing into sentimentality or bathos, of buttonholing the reader and trading upon what has been called "unearned emotion." One could fill up Yankee Stadium several times over with all of the mawkishly sentimental drivel passing itself off as genuine poetry that has fallen on the wrong side of this line. It is perhaps the commonest of faults among inexperienced writers, and even great poets are not immune to this kind of error. Consider this line by Shelley:

I fall upon the thorns of life—I bleed!

The question arises, has Shelley gone too far into self-pity and sentimentality here? Many readers and critics tend to think he shows a momentary lapse of taste.

Though quite real, self-pity is often considered an unlovely human emotion. Yet, because it is human and because nothing human is outside the scope of the poet's pen, a great poet like Shakespeare can examine it, even confess it, honestly. Fortunately, in the following sonnet, he also points the way out of the emotional swamp of self-pity.

Notice how, toward the end of the poem, there is a change in the direction of the thought, a swerving or veering, as if from a thesis to an antithesis, or from a problem stated to a resolution discovered. This shift is quite typical of the sonnet's structure, and is one of its traditional hallmarks. At the beginning the author is wallowing in self-pity, down on himself, and depressed. He discovers that the way out of his thoughts of self is to think on another, his lover, and the entire mood of the poem is lightened, ending on a note of celebration.

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes,

When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon myself, and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man's art and that man's scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee; and then my state

Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate;

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

If there are hidden laws of the operation and economy of our human emotions, no class of investigators or interpreters have studied and observed them more closely or with greater results than the poets. The founder of psychotherapy Dr. Sigmund Freud resorted time and again to the poets and playwrights to discover the terms with which to describe fundamental motives and workings of the human mind. Shakespeare's plays and poems alone constitute a veritable textbook on the inner workings of human behavior.

Poets not only accurately describe and analyze powerful emotions, they also convey or evoke them. Sometimes, as in the following poem by William Blake, they seem to do both. Some inner laws of the operations of malice and vengeance are described, and the speaker finally embodies these emotions, which gives the analysis an added, high-voltage charge.

A POISON TREE

I was angry with my friend:

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

And I watered it in fears,

Night and morning with my tears;

I sunned it with smiles

And with soft deceitful wiles.

And it grew both day and night,

Till it bore an apple bright;

And my foe beheld it shine,

And he knew that it was mine,

And into my garden stole

When the night had veiled the pole:

In the morning glad I see

My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

Emotion is also the motivating force of most poems of political protest and social criticism. The smarting wince we feel when we witness an injustice may turn quickly to anger, outrage, and indignation. The same cry against oppression and the abuse of power and wealth sounded by the Old Testament prophets (such as Isaiah or Jeremiah) can be heard throughout English and American poetry and down to the present day.

At the time of the great flowering of English Romanticism, the British government had retrenched into a reactionary stance, halting or reversing much-needed societal reforms in fear and horror of the excesses of the French Revolution, raging across the English Channel. It was a time of abject political reversal for the liberal poets, who envisioned mankind progressing toward a freer and more equable society. Witness part of Shelley's devastating summary of the situation from "England in 1819":

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying king;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,---mud from a muddy spring:

Rulers, who neither see, nor feel, nor know,

But, leech-like, to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow;

A people starved and stabbed in the untilled field;

An army which liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

This same despair of wretched social, moral and political conditions brought this damning indictment from Blake a few years earlier in "London."

I wander through each chartered street,

Near where the chartered Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

Near where the chartered Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

Reforms envisioned by the British poets eventually came to England, and it is not far fetched at all to state that England's poets spurred this progress. Perhaps Shelley did not overreach when he said, "Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world." When poets harness their outrage and channel it into emotionally powerful poems of social or political persuasion, their art is often in service to humanity in its quest for liberty and justice.

IV.

With the music of verse, richness of description, the wonder of creative imagination, marvels of metaphor, and the force of emotion, poetry can educate, ennoble, motivate, and enlighten us. Poetry can also help us appreciate the plenitude, brevity, and beauty of human life. I hope I have given in this essay some idea of how these elements, coming together, constitute what we might mean by the word "poetry." Poetry need not be hemmed in by a formulaic definition, and would be sure to break out of it if it were.

Many of you reading this are presently wearing the uniform of one of the branches of the Armed Services, or are perhaps closely related to a service member. I want to tell you briefly about four men who served in the military during World War II. One of these studied the rhymes of Edgar Allen Poe while scrunched down in a foxhole in Italy, trying not to get his head blown off. Another was present at the liberation of the Nazi extermination camps, and grappled with this in his poetry. Another fought at the Battle of the Bulge. In later life, each of these four went on to publish their own work, and each of them in their turn received the coveted Pulitzer Prize in poetry. Two of them were appointed United States Poet Laureate. Today their poems have entered into the great canon of American literature, where they will remain for succeeding generations to enjoy. Their names are Richard Wilbur, Louis Simpson, Howard Nemerov, and Anthony Hecht, and they were soldiers as well as poets. Some sixty years after they faced battle as young men, Wilbur and Simpson recorded their war poems for the Operation Homecoming CD to help today's troops better process their own wartime experiences. The lives and works of these four men indicate that there is no inherent conflict between military service and a love of poetry.

© Dan Rifenburgh

|

| https://www.pinterest.com/pin/422353271305202172/ |

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/11/what-is-a-poem/281835/

When I used to ask students what a poem is, I would get answers like “a painting in words,” or “a medium for self-expression,” or “a song that rhymes and displays beauty.” None of these answers ever really satisfied me, or them, and so for a while I stopped asking the question.

Then one time, I requested that my students bring in to class something that had a personal meaning to them. With their objects on their desks, I gave them three prompts: first, to write a paragraph about why they brought in the item; second, to write a paragraph describing the item empirically, as a scientist might; and third, to write a paragraph in the first-person from the point-of-view of the item. The first two were warm-ups. Above the third paragraph I told them to write “Poem.”

Here is what one student wrote:

PoemI might look weird or terrifying, but really I’m a device that helps people breathe. Under normal circumstances nobody needs me. I mean, I’m only used for emergencies and even then only for a limited time. If you’re lucky, you’ll never have to use me. Then again, I can see some future time when everybody will have to carry me around.

The item he had brought to class? A gas mask. The point of this exercise wasn’t only to illustrate the malleability of language or the playfulness of writing, but to present the idea that a poem is a strange thing which operates as nothing else in the world does.

I suppose most of us have known poems are strange ever since we were infants being put to bed with lullabies like “Rock-a-bye baby,” or were children being taught prayers that begin “Our Father who art in Heaven….” The questions soon arose: What idiot put that cradle in a tree? And what’s art got to do with my Daddy-God? But this kind of strangeness we got used to. And later, at some point in school, we asked or were made to ask again: What is a poem?

For example, in high school my English teacher handed me Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” and said I had to write an essay about what it meant. I couldn’t make heads or tails out of the assignment, and the poem became the object of my hatred. The poem seemed willfully not to make sense. I soon found every poem to be an irritation, a blotch of words, a ludicrous puzzle that got in the way of true understanding as well as true feeling.

Unless you are a poet or writer, it’s likely that poems have apprehended you less and less as the years have passed. Occasionally, in a magazine or online you see one—with its ragged right edge and arbitrary-looking line breaks—and it announces itself by what it is not: prose that runs continuously from the left to the right margins of the page. A poem practically dares you not just to look but to read: I am different. I am special. I am other. Ignore me at your peril.

And so you read it and too often become disappointed by its blandness, how it can be paraphrased with an easy moral, such as “this too shall pass” or “getting old sucks”—how essentially it’s no different in content than most of the prose around it. Or, you become disappointed because the poem baffles initial comprehension. It’s inaccessible in its fragmented syntax and grammar, or obscure in its allusions. Nevertheless, you pat yourself on the back just for the trying.

How many of us believe poetry is useless? How many of us don’t even care to ask the question, “Is poetry useless?”

Comparatively, a poem moves a reader, physically or emotionally, very rarely. Other media are much better at bringing us to tears—television, the movies. And if we want the news, we read an article online or glean our Twitter feed. If we want something between tears and the news, we just stare at our children when they ask a question that sounds more like a statement: “Why do grown-ups drink so much beer?”

But seriously, isn’t a poem a home for deep feelings, stunning images, beautiful lyricism, tender reflections, and/or biting wit? I suppose so. But, again, other arts or technologies seem better at those jobs—novels offer us real or imaginary worlds to explore or escape to, tweets offer us poignant epigrams, painting and design offer us eye candy, and music—well, face it, poetry has never been able to compete with that sublime combo of lyrics, instruments, and melody.

There is at least one kind of utility that a poem can embody: ambiguity. Ambiguity is not what school or society wants to instill. You don’t want an ambiguous answer as to which side of the road you should drive on, or whether or not pilots should put down the flaps before take-off. That said, day-to-day living—unlike sentence-to-sentence reading—is filled with ambiguity: Does she love me enough to marry? Should I fuck him one more time before I dump him?

But such observations still don’t tell us much about what a poem really is. Try crowd-sourcing for an answer. If you search Wikipedia for “poem,” it redirects to “poetry”: “a form of literary art which uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language—such as phonoaesthetics, sound symbolism, etc.” Fine English-professor speak, but it belies the origins of the word. “Poem” comes from the Greek poíēma, meaning a “thing made,” and a poet is defined in ancient terms as “a maker of things.” So if a poem is a thing made, what kind of thing is it?

I’ve heard other poets define poems in organic terms: wild animals—natural, untamable, unpredictable, raw. But the metaphor quickly falls apart. Such animals live on their own, utterly unconcerned with the names humans put upon them. In inorganic terms, the poet William Carlos Williams called poems “little machines,” as he treated them as mechanical, human-engineered, and precise. But here too, the metaphor breaks down. A worn-out part on an automobile can be switched out with a nearly identical part and run as it did before. In a poem, a word exchanged for another word (even a close synonym) can alter the entire functioning of the poem.

The most productive thing about trying to define a poem through comparison—to an animal, a machine, or whatever else—is not in the comparison itself but in the arguing over it. Whether or not you view a poem as a machine or a wild animal, it can change the machine or wild animal of your mind. A poem helps the mind play with its well-trod patterns of thought, and can even help reroute those patterns by making us see the familiar anew.

An example: the sun. It can be dictionary-defined as “that luminous celestial body around which the earth and other planets revolve.” But it can also be described as a four-year-old intuits while staring out the car window on a long winter’s drive: “Mom, isn’t the sun just a kind of space-heater?” Another example: honey. According to the dictionary, it’s “a sweet, sticky yellowish-brown fluid made by bees from the nectar they collect from flowers.” According to mothers everywhere, it’s “bee spit which can kill an infant.”

The poem as mental object is no difficult reach, especially if we consider the extent to which pop song lyrics can literally get stuck, as the neuroscientists tell us, in the form of “earworms” in the synapses of the brain. The intermingling of words and melody has an historied potency going back to schoolyard rhymes that call attention to metalanguage: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” That line itself can hurt, paradoxically, as it perhaps invokes the memory of being called hideous names, whether personalized (Yakich jock-itch) or generalized (camel-jockey).

But when are words most like sticks and stones?

Consider a poem lurking in the pages of The New Yorker. There it is staring you in the face: Do you read it as well as it reads you? In terms of ink on paper, it does nothing more than the prose around it, but in terms of apprehension, it draws in your eye and places the poem in a rarefied position and a totally ignorable one all at once. Oh, look, it’s a precious little chit of words! What a waste of my time!

But there’s also all that white space surrounding it. How much did that cost? The magazine gave up valuable space to print the poem instead of printing a longer article or an advertisement. Nobody bought the copy of The New Yorker for the poem, except perhaps for the poet who wrote it. A poem is a text—a product of writing and rewriting—but unlike articles, stories, or novels, it never really becomes a thing made in order to become a commodity.

A new novel, a memoir, or even a short story collection has the potential for earning big bucks. Of course, this potential is often not realized, but a new book of poems that yields its author more than a thousand-dollar advance is exceedingly rare. Publicists at publishing houses, even the largest ones, dutifully write press releases and send out review copies of poetry collections, but none will tell you that they expect a collection to sell enough copies to break even with the costs of printing it. Like no other book, a book of poems presents itself not as a thing for the marketplace, but as a thing for its own sake.

The epitome of such “sake-ness” are poems that put their “made-ness” right in your face. Variously called visual poems, concrete poems, shape poems, or calligrammes, George Herbert’s “Easter Wings” is a canonical example from the 17th century:

The poem’s wings, of birds or angels, coincide or illustrate the textual content: the speaker’s desire to reach skyward toward the Lord. The visual form provides what we might call a little bonus or lagniappe in meaning, and it also makes us notice the poem as more than a raggedly blotch—the blotch itself is meaning.

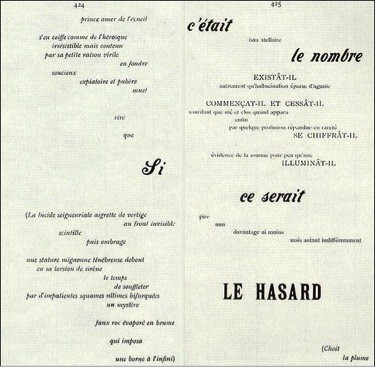

In the 19th century, the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé pushed this page-as-canvas idea even further in Un Coup de Dés (“A Throw of the Dice”). His book-length poem not only manipulates black type, font styles, and white space, but also it exploits the boundaries of the page itself, including the gutter—the seam in the middle of a book—which serves as the alley in which the “dice” (i.e., words) are thrown.

|

| A spread from Stéphane Mallarmé's book-length poem Un Coup de Dés. |

Which brings us back to poetry’s contemporary predicament: a poem that is so strange, so other, is also a poem many feel they might as well ignore. Here’s a poem from the 1960s by Aram Saroyan:

lighght

Yes, that’s the whole poem. I know, it seems asinine. When I wrote it on the board and asked my students to examine it, one said, “How do you even read it aloud?” When we tried, we began to understand the intent of the poem. The word “light” seems to be implied, but what’s with the apparent typo? After a long silence, another student said, “That’s the point—in the ordinary word ‘light’ we don’t pronounce the ‘gh’—the ‘gh’ is silent, and the double ‘gh’ makes us realize that even more.” The poem calls attention to the system of language itself—the stuff of letters in combination—and the relationship between sound and sense. The familiar—a plain word such as “light”—has been made new if only for a brief moment. In Saroyan’s own words: “[T]he crux of the poem is to try and make the ineffable, which is light—which we only know about because it illuminates something else — into a thing.”

When we come across a poem—any poem—our first assumption should not be to prejudice it as a thing of beauty, but simply as a thing. The linguists and theorists tells us that language is all metaphor in the first place. The word “apple” has no inherent link with that bright red, edible object on my desk right now. But the intricacies of signifiers and signifieds fade from view after college. Because of its special status—set apart in a magazine or a book, all that white space pressing upon it—a poem still has the ability to surprise, if only for a moment which is outside all the real and virtual, the aural and digital chatter that envelopes it, and us.

One might argue that the page is just a metaphor for all that can’t be put on it, and that a poem is merely a substitution, for better or for worse, for a lived feeling or event. And yet, one Jewish tradition admonishes that parents teach their children to love the Talmud not by reading it to them first, but by having them lick honey from its pages. That would seem, to me, an ideal way to experience both bee spit and poetry.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2009.16 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1902 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/reading-in-mexico-56a1c0f23df78cf7726da4d7.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment