|

| https://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=7668 |

A Sense of Doubt blog post #2100 - Being Extraordinary in the face of disaster

This post may be anti-climactic for a milestone like THREE THOUSAND posts, but that's okay. I am busy with grading and conferences with students.

And this is still a very relevant set of articles from WONKETTE, even though they were published months ago.

That's it.

LOW POWER MODE.

Back to work.

A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster

Paperback –

August 31, 2010

by Rebecca Solnit

A quick suggestion: When disaster strikes, and at any other time, don't pick Yr Doktor Zoom to be the leader. He has the organizational skills of a hyperactive chihuahua. Also, "Hyperactive chihuahua" is probably redundant. My point here is that in last week's Nice Things, I pointed out that the book I'd picked for Wonkette Book Club, Rebecca Solnit's 2009 A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, seems only to be widely available in ebook and audio formats. I set up a Twitter poll to ask if we should go ahead and read the book together anyway, and out of the 19 responses, only one chose "nah, I prefer print."

Just one small problem: I never actually said "OK then, hooray for us we are going ahead and reading this fine book!" So while I did include a tentative reading schedule in last week's column, I would feel pretty darn silly going ahead and trying to lead a discussion of the first two sections of the book, only to find a lot of you saying in the comments, "Oh shoot, I was waiting to hear back before spending $12.99 on it in any of the popular e-book formats like Amazon Kindle (with a portion of sales going to Wonkette).

OK, consider it official: We shall be reading and discussing A Paradise Built in Hell through Section II (that's up through the chapter on disaster movies, "Hobbes in Hollywood") for next week.

Yes, I was almost exactly this chaotic and loosely organized when I taught college writing classes, too. It's a wonder anyone ever learned anything.

Fortunately, I did ask you to give a listen to this excellent Chris Hayes interview with Rebecca Solnit about her book's thesis, which is that when the norms of everyday life are torn apart by disaster, there's lots of evidence to suggest that we don't turn into Lord of the Flies monsters, but instead, humans tend to help each other. It's often "anarchy" in the ideal sense, characterized by mutual aid and sharing, not panicked mobs running amok. So that's our more scaled-down topic for today: Give a listen to the interview, from Hayes's terrific podcast "Why Is This Happening?" (or, if you prefer, read the transcript here), and we shall discuss! Oh, look, I even found an embeddable version. Thanks, MSNBC overlords!

Here are the things that stood out for me:

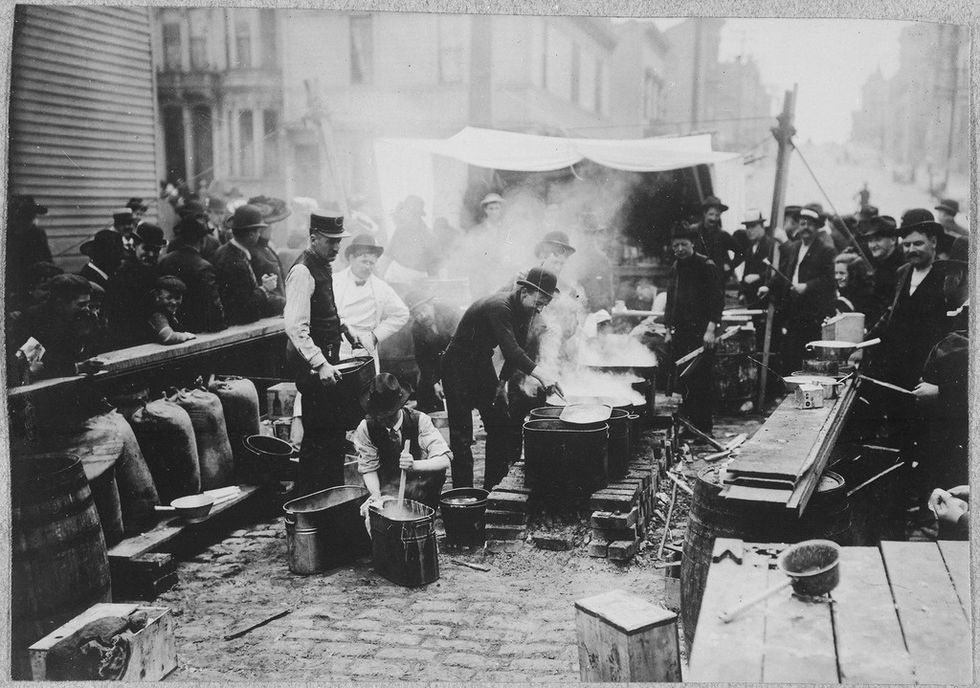

Tough-minded optimism: Solnit explicitly rejects the Hobbesian idea that, without the constraints of law and social order, people descend into a war of all against all for scarce resources. Instead, people tend to help each other, creating on the fly ways to get by, like the outdoor community kitchens that sprung up all over San Francisco following the 1906 earthquake. It wasn't safe to have fires inside, so they went outdoors. But instead of just cooking for their own families, neighbors set up kitchens to feed whoever needed food, with food brought in by those who had it or could get it, often from butchers and meat packers who wanted to see their stock put to use rather than let it spoil. (Fast-forward to 2020 and restaurateurs giving away their perishables or preparing meal boxes on a pay-what-you-can basis.)

But Solnit's no starry-eyed idealist either; she acknowledges "not everybody behaves well in these moments," like the white supremacist vigilante in a New Orleans suburb who, following Hurricane Katrina, shot three black men evacuating from the disaster. The shooter appears to have attacked Donelle Harrington and two other evacuees simply because he thought he could get away with it. Harrington was rescued by some good Samaritans who got him to a hospital, but the horrifying thing is that the shooter's assumption was almost right: the world only learned about Harrington's shooting years later when ProPublica reporter AJ Thompson started digging into the case. (Solnit merely says the shooter "pretty much did" get away with it, although Thompson's reporting did lead to a federal investigation. After repeatedly being found incompetent to stand trial, the shooter was found competent in 2018 and pled guilty. But in February 2019, five days after being sentenced to ten years, he died in jail while awaiting transfer to prison, apparently of natural causes. Did he "get away" with the shooting? He had 13 more years of freedom, if nothing else.)

The authorities may make things worse: While Solnit acknowledges that sometimes political leaders do pretty well in a disaster (she says Gavin Newsom is doing a fine job in response to the pandemic, though national "leadership" is flailing), she argues that the more authorities fear the populace getting out of control following a disaster, the more likely those authorities are to cause their own disaster. In San Francisco, the mayor gave a shoot to kill order against looters, and Gen. Frederick Funston, who commanded troops at The Presidio, was happy to get tough. Over 500 civilians may have been shot to death because they'd committed petty theft, or because solidiers thought they might have. Says Solnit,

One of the horrible stories of 1906 was a storekeeper who'd opened his store for people to haul stuff away before it burned down, because the fire was approaching and some of the armed authorities deciding that these must be looters and shooting people, shooting somebody who was taking something the storekeeper had invited him to take.

The fires that destroyed much of the city were largely the result of inept attempts to create firebreaks to prevent fires spreading. San Francisco's fire chief died in the earthquake, and the military geniuses who took over tried to blow up buildings to prevent fires. But they did it all wrong, in some cases using flammable powder that set new fires, and in other cases blowing up buildings full of flammable chemicals and other materials that spread burning debris even farther.

And also, they were trying to force people to evacuate their own neighborhoods. So, instead of allowing people to do what was really effective firefighting, which was wet gunny sacks and bucket brigades, putting out fires by hand, they were often driving people away from their own homes and neighborhoods. I believe some of the people they shot were because they were trying to defend their neighborhood. And so, they were actually doing the right thing, and the authorities were doing the wrong thing.

See also Katrina, where the authorities and the media spread untrue rumors of massive outbreaks of looting, rape, and murder based on nothing. People were scared, but — as further documented in the excellent podcast Floodlines — nobody was shooting at rescuers or at police helicopters. There were no rape gangs. It just didn't happen. But the myths spread anyway.

Racism is deadly: See New Orleans again. In addition to the racist shootings of black evacuees by white civilians and police, there was also the ugly stereotyping of people trying to survive, summed up in this notorious pair of photo captions:

Solnit also points out that "looting" is a word that's generally only applied during disasters, to refer to property crimes that would normally be petty theft or shoplifting. And she recounts this shameful media response:

One of the most heartbreaking things, and you can probably still find the video on YouTube, is a major network personality inside the [...] Walmart in new Orleans, where a lot of stuff was being taken, including by the police in one of the country's most corrupt police forces at the time. But a small black boy has taken a pink t-shirt and this undoubtedly wealthy hosts sneers at him, "I don't think that's your color." I just watched that and I'm like, "Do you understand that this kid's mom could've swamped through raw sewage, or his aunt could have swamped through benzene and toxic chemicals in this incredibly hot city with 80% underwater? This kid is probably a hero trying to find clean clothes for the woman in his little community, and you're making fun of him on the national news."

She also suspects that weird regard for protecting private property in a cataclysm (the store's entire stock would surely have been written off as an insurance loss anyway) is at least in part behind some of the push to "reopen" America right now. Citing people who say we need to get the economy going no matter how many might get sick or die, Solnit says,

I feel like, in a way, I never quite recognized before, these are people for whom dead things like money are alive and beloved in a tender hearted way, and living beings are dead to them in some way.

And so on. So let's discuss a few things before we start really talking about the book next week:

1) What surprised you in the interview? What's going to stick with you?

2) What do you think of Solnit's suggestion that people in a disaster tend to be more cooperative than competitive?

3) What about her point about authorities' tendency to make things worse by trying to reimpose "order"? What warnings does that suggest for liberal lovers of Big Gummint?

4) How do you see Solnit's ideas playing out in the current pandemic?

5) What other stuff have you read/watched that looks at similar themes? Particularly, can you think of any post-apocalyptic fictions where instead of a Walking Dead hellscape where fellow survivors are as deadly as the zombies, people do the mutual aid thing? I can think of at least one recent example, Cory Doctorow's novel Walkaway. It's about a failing USA where large parts of the country are abandoned, while some urban centers are still enclaves of wealth and privilege. With widespread availability of DIY 3D printing tech, lots of people just drop out and build communes, but they aren't necessarily safe, because there are indeed assholes out there too, not to mention those in power who don't like anarchy. It's a novel of ideas that I just loved when I read it a few years back. See also Ursula K. Le Guin's The Dispossessed for another anarchic not-quite-utopia.

Have a great Sunday, and next week we'll start discussing Solnit's book for sure! So let's try this updated schedule!

May 24: A Paradise Built in Hell through Section II. ("Hobbes in Hollywood")

June 7: finish the rest of the book.

Clear as mud? Indeed it is!

Programming Note: As with other Book Club posts, I'd like to keep discussion focused just on this topic, even though there's not technically a "book" yet. Please save your off-topic comments for the Open Thread, which will be along in a while. Thanks! I will be deleting off topic comments, but don't worry, you wont' get in trouble for that.

["Why Is This Happening" podcast and transcript / Floodlines / A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster at Amazon: $12.99 Kindle e-book. Links to other e-book versions here, also $12.99]

On a weekend where America will mark 100,000 deaths from COVID-19 and the New York Times print edition's front page is dedicated to listing some of them (about a thousand), this seems like a good time to talk about the questions Rebecca Solnit asks at the beginning of in her 2009 book A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster: "Who are you? Who are we?" And in times of crisis, she says, those are life and death questions.

Here is some of who we are:

Unfortunately, here too is another snapshot of some of who we are, in reply to a tweet of that front page:

There's also been a bit of rightwing crowing over an error in the front page list, which mistakenly included a murder victim, so perhaps the pandemic isn't real. And others just said hurr-hurr, you said the losses are "incalculable" but you put a number on it, hurr.

But look at the small number of "likes" for those tweets up there. Polls consistently show Americans are not on the side of the idiots, however much noise they make. While it's easy to forget that the noisy jerks aren't representative — good lord, I've just given them too much attention already here — that noise-to-signal ratio illustrates a misunderstanding Solnit wants to dispel.

When things fall apart, most people don't become frenzied mobs, and the post-disaster landscape isn't a hell world of survivors who are as dangerous to each other as the disaster was. Most people just quietly get to the business of helping other people, and out of disaster can come solidarity and new ways of seeing the world.

And if that's who we are — or can be — in a disaster, Solnit asks, why aren't we more like that all the time?

For this week, we'll be discussing Paradise Built in Hell through the end of Section II, the chapter titled "Hobbes in Hollywood."

In some ways, I've been reading Paradise Built in Hell as a reply to this single illustration from that hilariously bad 2006 National Rifle Association comic book about why America needs all the guns it can get. Here's the NRA's answer to the inevitable nightmare of societal breakdown, John Q. Whiteguy grimly defending his concerned (but not terrified) family with a shotgun as the mob advances:

Not surprisingly, it's also the image of post-disaster chaos we see in Hollywood productions and, all too often, the media: Panic, literally, in the streets (which was also the title of a 1950 movie about a hero coroner trying to prevent same, by keeping a lid on news of a possible plague outbreak getting out. People just couldn't handle such information, supposedly).

But as we mentioned last week when we discussed that Chris Hayes interview with Solnit, this is the reality of people in the streets following the 1906 earthquake: they set up soup kitchens and fed anyone who showed up.

They also put up joking signs about the shared privations, like "Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may have to go to Oakland."

Also as we mentioned last time, the problem is that institutions and political leaders all too often assume they need to prepare for the first image, not the latter, so they may do more harm than good. The military in San Francisco shot people for looting, but also on suspicion of looting, or even carrying things away from their own homes. And rumors about mobs of marauding gangs in New Orleans slowed getting help to survivors of Hurricane Katrina, not to mention reinforcing racial stereotypes.

Here's a useful term for that "fear-driven overreaction," in which suddenly authorities think it makes all sorts of sense to issue shoot-to-kill orders over looting: "Elite panic." The term was coined by disaster sociologist Kathleen Tierney, who said its elements include "fear of social disorder; fear of poor, minorities and immigrants; obsession with looting and property crime; willingness to resort to deadly force; and actions taken on the basis of rumor." Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

But that's not right at all, as Solnit demonstrates again and again. In the 1930s, British military planners worried that if Germany bombed British cities, there'd be massive outbreaks of insanity, panic, and depression among the civilian population; even Winston Churchill feared the populace would be reduced to helplessness and would be such mental basket cases that they'd overwhelm the government. Historian Mark Connelly wrote, after the war, that the the working class

was thought to be particularly susceptible to panic and disillusionment in the face of an aerial onslaught. . . . When it came to shelters, the government considered it best to protect people in small groups. Communal shelters, it was argued, would create conditions for an agitator's field day. It would also encourage a '"deep shelter'"mentality, leading people to become molelike tunnel dwellers who would never resume their jobs in vital war industries.

Instead, during the Blitz, Britons adapted, and while only a small percentage of Londoners actually used Underground stations as bomb shelters (there goes another myth), the overall attitude was endurance, not panic.

And wouldn't you know it, British and American leaders still took away the wrong conclusion: Londoners' fortitude, they decided, had more to do with the British "character," not with any universal human tendencies of resilience and community. Solnit notes the postwar US Strategic Bombing Survey found that massive bombings of cities didn't "break" the enemy population's spirit, and that specifically, German civilians were no more "demoralized" than the British population. But then the analysts came to this weird conclusion:

Under ruthless Nazi control they showed surprising resistance to the terror and hardships of repeated air attack, to the destruction of their homes and belongings, and to the conditions under which they were reduced to live. Their morale, their belief in ultimate victory or satisfactory compromise, and their confidence in their leaders declined, but they continued to work efficiently as long as the physical means of production remained. The power of a police state over its people cannot be underestimated.

Britons: Resilient despite terrible suffering because of their special national character. Germans: Resilient despite terrible suffering because their Nazi oppressors maintained mind control over them.

And we wonder why "bombing them back to the stone age" — whichever "them" we're bombing at the moment — doesn't seem to work.

Another idea that really stood out for me in this part of the book was this observation from Charles E. Fritz, who worked on the US Strategic Bombing Survey, went on to graduate work in sociology, and helped found the field of disaster studies. Fritz rejected the notion that disaster weakens social bonds; rather, he believed, the breakdown of normality can strengthen them. Solnit summarizes Fritz's "first radical premise":

everyday life is already a disaster of sorts, one from which actual disaster liberates us. [... due to] "the failure of modern societies to fulfill an individual's basic human needs for community identity."

Later he describes more specifically how this community identity is fed during disaster: "The widespread sharing of danger, loss, and deprivation produces an intimate, primarily group solidarity among the survivors, which overcomes social isolation, provides a channel for intimate communication and expression, and provides a major source of physical and emotional support and reassurance."

And so it's reasonable to ask: If we're capable of great compassion, sharing, and solidarity in a disaster, how can we bring such capacities to everyday life? The solution can't be a permanent state of disaster, thank you very much. I think of the Misfit in Flannery O'Connor's "A Good Man is Hard to Find," saying of the grandmother he's just murdered: "She would have been a good woman [...] if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life." How can we come to that radical recognition of shared humanity, without a crisis?

So there's Discussion Question One, I'd say. Especially, how does that relate to your experience of this crisis, right now (if it does)?

A couple more:

Discussion Question Two: Solnit writes, "The elite often believe that if they themselves are not in control, the situation is out of control, and in their fear take repressive measures that become secondary disasters." That sounds about right to me; how do you see it playing out in the pandemic? To what degree does it explain the short-sighted insistence on "reopening," even if it leads to more illness?

Discussion Question Three: Um ... are you guys reading this book? I'm enjoying talking about it, but if nobody else is actually reading the book, should I finish up discussing the thing in two weeks (June 7)? Let me know in the comments. I'm inclined to keep on yapping about it; the next chapters discuss the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, the 9/11 attacks, and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the failure of a) the levees and b) the state and federal response.

Programming Note: As ever with Book Cub posts, please limit your discussion to the book itself and current events observations related to this post. Please save your off-topic comments for the actual Open Thread, which will be along in a bit. So yes, if you want to talk about COVID-19 as it relates to Solnit's book or the ideas in this here post, that's definitely on topic. But if it's just the latest stupid thing Trump said, maybe save it for later. Thanks! I will be deleting off-topic comments, but don't worry, you wont' get in trouble for that.

[A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster at Amazon: $12.99 Kindle e-book. Links to other e-book versions here, also $12.99]

LOW POWER MODE: I sometimes put the blog in what I call LOW POWER MODE. If you see this note, the blog is operating like a sleeping computer, maintaining static memory, but making no new computations. If I am in low power mode, it's because I do not have time to do much that's inventive, original, or even substantive on the blog. This means I am posting straight shares, limited content posts, reprints, often something qualifying for the THAT ONE THING category and other easy to make posts to keep me daily. That's the deal. Thanks for reading.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2011.17 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1964 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment