A Sense of Doubt blog post #2175 - Baseball Players who Died in 2020

I have been working on this post for a while. Sadness. I love Baseball, and I am sad to see so many greats die in a single year, many of Covid-19.

And Aaron, who died in 2021, just after making a public show of getting his vaccine.

Here's tributes to the passing of so many greats and so many heroes. I previously wrote of Al Kaline and Tom Seaver, two of my greatest heroes. But here are the tributes for Joe Morgan, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Whitey Ford, Phil Niekro, and Don Sutton.

Thank you, gentlemen, for all the amazing Baseball.

I did the Hank Aaron post yesterday.

The older I get, the more my childhood heroes pass on. Goodbye Hammerin' Hank. Thank you for being AWESOME. #HammerinHank #HenryAaronRIP #BaseballLegends

A Sense of Doubt blog post #2174 - Hammerin' Hank Aaron - RIP

Hank Aaron Career Highlights

ESports Highlights - Hammerin Hank

Hank Aaron Memorial Service

14,753 views•Streamed live on Jan 26, 2021

Atlanta Braves

LIVE: A Celebration of Henry Louis Aaron

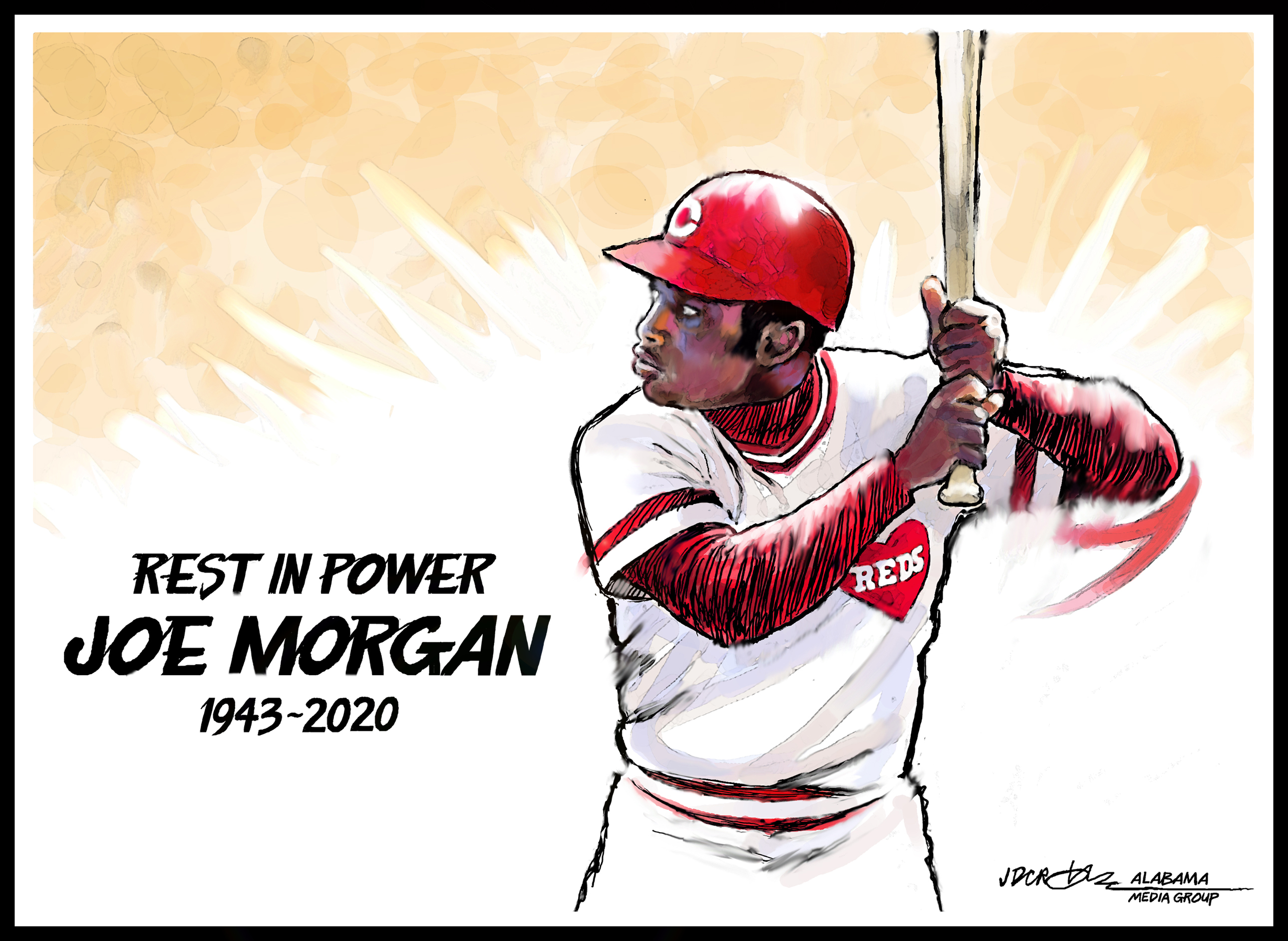

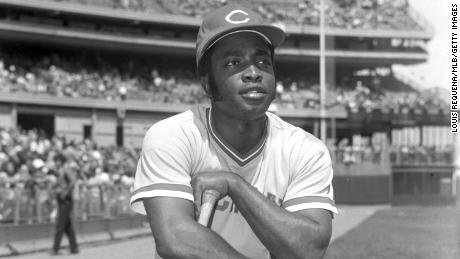

JOE MORGAN

MLB great Joe Morgan remembered by Mike Schur, creator of 'Parks and Recreation' and 'The Good Place'

Pablo Torre - Oct 14 - 2020

On Sunday, former Cincinnati Reds' second baseman and baseball broadcasting legend Joe Morgan died at the age of 77. The Hall of Famer's accomplishments are legion. The guy had two MVPs, two World Series titles, 10 All-Star appearances ... and one sports blog, named in his dishonor, called FireJoeMorgan.com.

For years FJM critiqued Morgan's baseball commentary through a sabermetric lens, becoming a cult hit in the early blogosphere. And it turned out that the man behind it, Mike Schur, was also the guy behind TV shows like "Parks and Recreation," "The Good Place," "Brooklyn Nine Nine," and "The Office."

In this Q&A, which originally aired on The ESPN Daily podcast, Schur discusses the site and what Morgan meant to him.

Pablo Torre: I just want to know first off, what went through your mind when you heard the news?

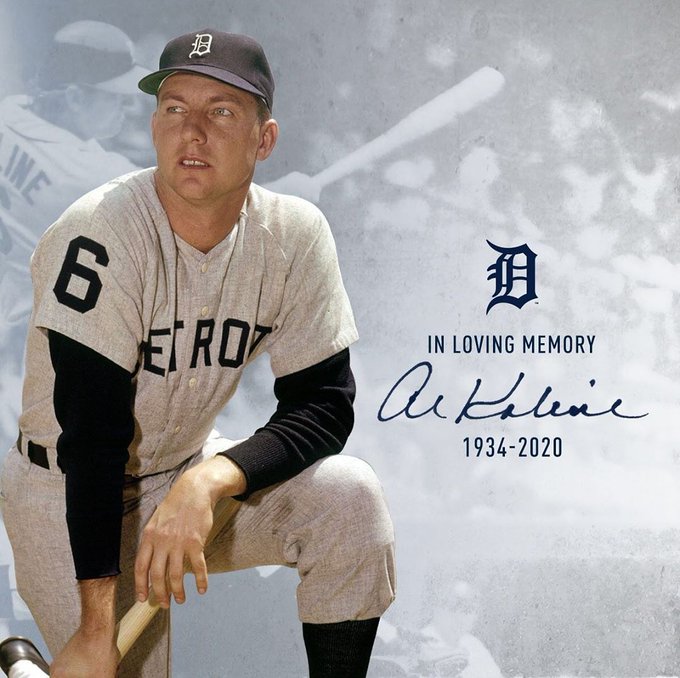

Mike Schur: Um, what went through my mind, purely sadness. Baseball's my favorite sport and I felt nothing but sadness that he was gone, especially in a week and a month that has also seen the passing of, uh, you know, a lot of other baseball greats, Tom Seaver and Al Kaline and Whitey Ford and all these people.

Kurkjian: Baseball keeps losing legends and Morgan might have been the mightiest.

Pablo: Describe for those who aren't familiar, the kind of tension, the dichotomy between being a site that considers Joe Morgan, maybe the best, second baseman ever, or one of the two best ever while also being a site that obviously criticized him quite publicly.

Mike: Yeah, we always regretted that we named the site Fire Joe Morgan, because we didn't want the guy to be fired, really. It was a crass sort of early internet version of, um, you know, making noise and banging on a pot and calling attention to yourself.

What we were complaining about was that this guy who, in his career did everything right, every single aspect of his game was incredible. He was an incredible defensive second baseman. He led the league in on base percentage four times. He was a 5-foot-7, second baseman who wants to lead the league in OPS. In fact, twice, I think led the league in OPS. He was a marvel.

Pablo: That's wild.

Mike: Yeah. And not only did he do everything right, he specifically did the things right that the sort of modern analytic movement has shown to be the most valuable possible things you can do. He was just an incredible player in exactly the ways that the sort of "Moneyball" era was beginning to point out how undervalued guys like him actually were.

And then he got into the broadcast booth. And it also spoke to this kind of generational divide where this sort of old-school, '60's, '70's kinds of players we're fighting against the modernization of the way that we look at the game analytically. And so he became a sort of poster child for us and for other people, because he was the flagship commentator on the Sunday Night Baseball broadcast on ESPN. He was there all the time, calling games and analyzing games. And so as a result, we just kind of located all of our discontent onto him specifically.

But it really could have been ... we really could have located it on any other of a hundred different people.

Pablo: How should we be remembering Joe Morgan?

Mike: Joe Morgan was a phenomenal baseball player. So I think we should first remember him that way, because that's the more important thing. And then maybe you remember him as a guy who transitioned into a broadcasting career, unfortunately at the exact moment that this gigantic argument between the past and the future was boiling over.

And the generation that's come after him, uh, now, you know, we used to say, when we were writing the site, we used to joke that we would give it up, and stop working on it at the moment that you would be watching a baseball game and instead of showing batting average, home runs and RBI for a hitter's statistics, you would see like OPS+ and wins created above average and whatever. And that happens now. It was the beginning of that process at the exact moment that he was doing the flagship baseball broadcast on ESPN.

And I think it's unfortunate that he happened to be in that place at that time. Because if he hadn't been, I think we would only remember him the way we should, which is the greatest or second-greatest, second baseman of all time.

Baseball Hall of Famer Joe Morgan dies at 77

ESPN NEWS SERVICES - OCTOBER 12, 2020

Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Morgan, a key member of the Cincinnati Reds' famed Big Red Machine, died Sunday. He was 77.

Morgan died Sunday at his home in Danville, California, family spokesman James Davis said in a statement Monday.

Morgan struggled with various health issues in recent years, including a nerve condition, a form of polyneuropathy.

Morgan was a two-time National League Most Valuable Player, a 10-time All-Star and a five-time Gold Glove Award winner. He is widely regarded as one of the best second basemen in baseball history, and he gained renown for his 25-plus years as a broadcaster after his playing career.

"Major League Baseball is deeply saddened by the death of Joe Morgan, one of the best five-tool players our game has ever known and a symbol of all-around excellence," MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. "Joe often reminded baseball fans that the player smallest in stature on the field could be the most impactful."

Morgan spent the majority of his 22-year career with the Reds and the Houston Astros franchise. Along with Pete Rose and fellow Hall of Famers Johnny Bench and Tony Perez, Morgan helped the Reds win back-to-back World Series championships in 1975 and 1976. Cincinnati also reached the World Series in 1972, Morgan's first year with the Reds.

"Joe Morgan was quite simply the best baseball player I played against or saw,'' Bench texted to The Associated Press.

Morgan was the NL MVP in 1975 and 1976 and was named an All-Star in each of his eight seasons with the Reds. He was a .271 career hitter, with 268 home runs, 1,133 RBIs, 1,650 runs scored and 689 stolen bases, 11th in baseball history.

There were moments of silence held at Petco Park in San Diego before the Tampa Bay Rays and Astros played Monday in Game 2 of the American League Championship Series and at Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas, before the Los Angeles Dodgers and Atlanta Braves met in the NL Championship Series opener.

"He meant a lot to us, a lot to me, a lot to baseball, a lot to African Americans around the country. A lot to players that were considered undersized,'' said Astros manager Dusty Baker, a longtime friend and National League rival. "He was one of the first examples of speed and power for a guy they said was too small to play.''

Morgan first played in the majors in 1963, when the Astros were the Houston Colt .45s. He was traded to Cincinnati in November 1971 as part of an eight-player deal. He played the next eight years with the Reds.

"The Reds family is heartbroken. Joe was a giant in the game and was adored by the fans in this city," CEO Bob Castellini said in a statement. "He had a lifelong loyalty and dedication to this organization that extended to our current team and front office staff. As a cornerstone on one of the greatest teams in baseball history, his contributions to this franchise will live forever. Our hearts ache for his Big Red Machine teammates."

Morgan spent the 1980 season with Houston, helping the Astros to an NL West title. He played two years with San Francisco -- hitting a home run on the final day of the 1982 season against the rival Dodgers to knock the defending champions out of the playoffs -- and later was reunited with Rose and Perez in Philadelphia.

Morgan hit two home runs in the 1983 World Series, in which the Phillies lost in five games to Baltimore, and he tripled in his final at-bat.

Morgan finished as a career .182 hitter in 50 postseason games. He played in 11 series and batted over .273 in just one of them, a stat that surprises many, considering his big-game reputation.

Raised in Oakland, California, Morgan returned to the Bay Area and played the 1984 season for the Athletics before retiring at the age of 41. He set the NL record for games played at second base and ranked among the career leaders in walks.

He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990. The Reds inducted him into their hall of fame and retired his number (8).

"He did it all, and he did it all the time,'' said Bench, the first member of the Big Red Machine to enter the Hall. "Great father and outstanding businessman. He was a friend to so many and respected by all."

Morgan started his broadcasting career in 1985 and worked at ESPN from 1990 to 2010, serving as a member of the network's lead baseball broadcast team. Morgan parted ways with ESPN after the 2010 season, when he returned to the Reds in the role of special adviser to baseball operations.

He also was board vice chairman of baseball's Hall of Fame and on the board of the Baseball Assistance Team.

"Joe was a close friend and an advisor to me, and I welcomed his perspective on numerous issues in recent years," Manfred said. "He was a true gentleman who cared about our game and the values for which it stands."

Morgan is survived by his wife of 30 years, Theresa; their twin daughters, Kelly and Ashley; and daughters Lisa and Angela from his marriage to Gloria Morgan. Funeral details were not yet set.

Morgan is among several Hall of Famers who have died this year, including Whitey Ford, Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, Tom Seaver and Al Kaline.

"All champions. This hurts the most,'' Bench said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Baseball keeps losing legends in 2020, and Joe Morgan might have been the smallest and mightiest of them all

Tim KurkjianESPN Senior WriterOctober 12, 2020

It has been a terrible year for so many people, for all of us, including baseball fans of a certain age.

Al Kaline.

Tom Seaver.

Lou Brock.

Bob Gibson.

Whitey Ford.

They were among our baseball heroes. They showed us how to play the game. I'm 63 years old and they were my childhood. And they all died in 2020.

And now, the littlest and mightiest, Joe Morgan, has died.

"There was no one better than Joe," said Johnny Bench, a former teammate and fellow Hall of Famer. "And I'm not just talking about second basemen. I'm talking about any position."

Morgan is regarded as one of the three greatest second basemen of all time. He is the only second baseman to win back-to-back MVP awards, which he did in 1975 and 1976 for the Cincinnati Reds' famous Big Red Machine. He made 10 All-Star teams, won five Gold Gloves and was elected to the Hall of Fame on the first ballot in 1990.

He had the fifth-most walks of all time, trailing only Barry Bonds, Rickey Henderson, Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. Morgan had 850 more walks than strikeouts. He had the 11th-most stolen bases ever. He hit 268 home runs; Henderson is the only player in history to match Morgan's totals in home runs and stolen bases.

"We played against the Reds in the '70 World Series," said Jim Palmer, a former Baltimore Orioles pitcher and a Hall of Famer. "But they weren't the Big Red Machine until they got Joe Morgan."

Sparky Anderson, manager of the Big Red Machine, once told me that Morgan "was a great player until the games counted most. Then he became one of the greatest players of all time."

Morgan's 1975 and 1976 seasons were historically great. He led the National League in OPS in both seasons, including a 1.020 in 1976. In those seasons combined, he stole 127 bases and was caught only 19 times. He grounded into five double plays. He walked 246 times and struck out 93 times. He scored 220 runs and drove in 205. He won a Gold Glove both seasons. Those teams were among the greatest of all time, maybe the best in the history of the NL, and their best player those two years was Joe Morgan.

"He did everything," said Bench, the Reds' catcher. "If you needed a walk, he walked. A hit, he got a hit. A double, he hit a double. A homer, he hit a homer. A stolen base, he stole a base. He was great defensively; the telepathy that he and I had going was amazing. It's because he was so smart, he understood every situation. He affected the outcome of every game. To those who knew him, no words were necessary. To those who didn't know him, no words are adequate."

Palmer was inducted into the Hall of Fame the same year as Morgan.

"I will never forget the call I got from Jack Lang [of the Baseball Writers' Association of America] that I had been inducted," Palmer said. "And then he told me that I would be going in with Joe. I thought, 'Oh my, I am going in with Joe Morgan!' He was that good of a player."

And to accomplish all of this at his size -- 5-foot-7, 160 pounds -- was the most remarkable part of Little Joe. He is, with Yogi Berra, perhaps one of the two best players of all time under 5-foot-8.

"Pound for pound,'' Palmer said, "Joe might be the best player of all time.''

Eduardo Perez is the son of Tony Perez, a former teammate of Morgan's in Cincinnati. "My dad always told me that Joe might have been a little guy, but he had the biggest heart of anyone on the field," Eduardo said. "And it wasn't just in baseball, it was in business, it was anything else he did. He was so competitive. He always had to be the best."

Morgan's favorite player of all time was another second baseman -- Hall of Famer Nellie Fox of the White Sox. Fox -- a left-handed hitter, as was Morgan -- finished with 2,663 hits and a .288 batting average, never struck out as many as 20 times in a season, made 15 All-Star teams and won the American League MVP in 1959. He was listed at 5-foot-10, but was closer to 5-foot-8.

"Why wouldn't Nellie be his favorite player?'' Bench said. "Nellie was a short second baseman that played with a lot of heart. And no one played with more heart than Joe Morgan.''

Morgan always used the smallest glove, the smallest I have ever seen used by a major leaguer. He wore such a small glove because, especially on the double play, he never had to search for the ball in his glove. As he once told me, with a smile, "you better have good hands to wear a glove that small."

I got to know Joe Morgan in the 21 years that he worked for ESPN in the booth on Sunday Night Baseball with Jon Miller. When Joe talked, I listened, because I have met very few people who knew the game better.

"He was the smartest baseball man I ever met," Hall of Famer Frank Robinson said. "No one understood the game better than Joe."

The only time I ever had an issue with Morgan was when I wrote many years ago that Dave Winfield was the oldest player ever to hit a home run in the postseason.

"You missed someone on that list," Morgan said.

I triple-checked. I told Morgan that, at the time, he was the second-oldest player to hit a homer in the postseason.

"OK, you're right," he said. "This time."

That was Morgan. A little guy, always fighting, always having to finish first. It is what he shares with the others who have died in 2020: Kaline, Seaver, Gibson, Brock, Ford. It was a different era, a different game, a different kind of player. And the passing of each has brought another loss.

"How much more gut-wrenching can we get?" Bench said. "Today, I lost my buddy, my teammate, my comrade, my dear friend for 40 years."

And then, with a crack in his voice, Johnny Bench did what he often does. He sang.

"To know, know, know you is to love, love, love you."

Remembering Joe Morgan

MLB Network

MLB Network looks back on the life and Hall of Fame career of the great Joe Morgan.

The Baseball Hall of Fame Remembers Joe Morgan

•Oct 12, 2020

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum mourns the passing of Class of 1990 member Joe Morgan. September 19, 1943 – October 12, 2020.

Johnny Bench remembers Joe Morgan on High Heat

Johnny Bench remembers Joe Morgan on High Heat

Bob Costas on Joe Morgan's passing, working in booth

Bob Costas on Joe Morgan's passing, working in booth

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21961550/78600492.jpg.jpg)

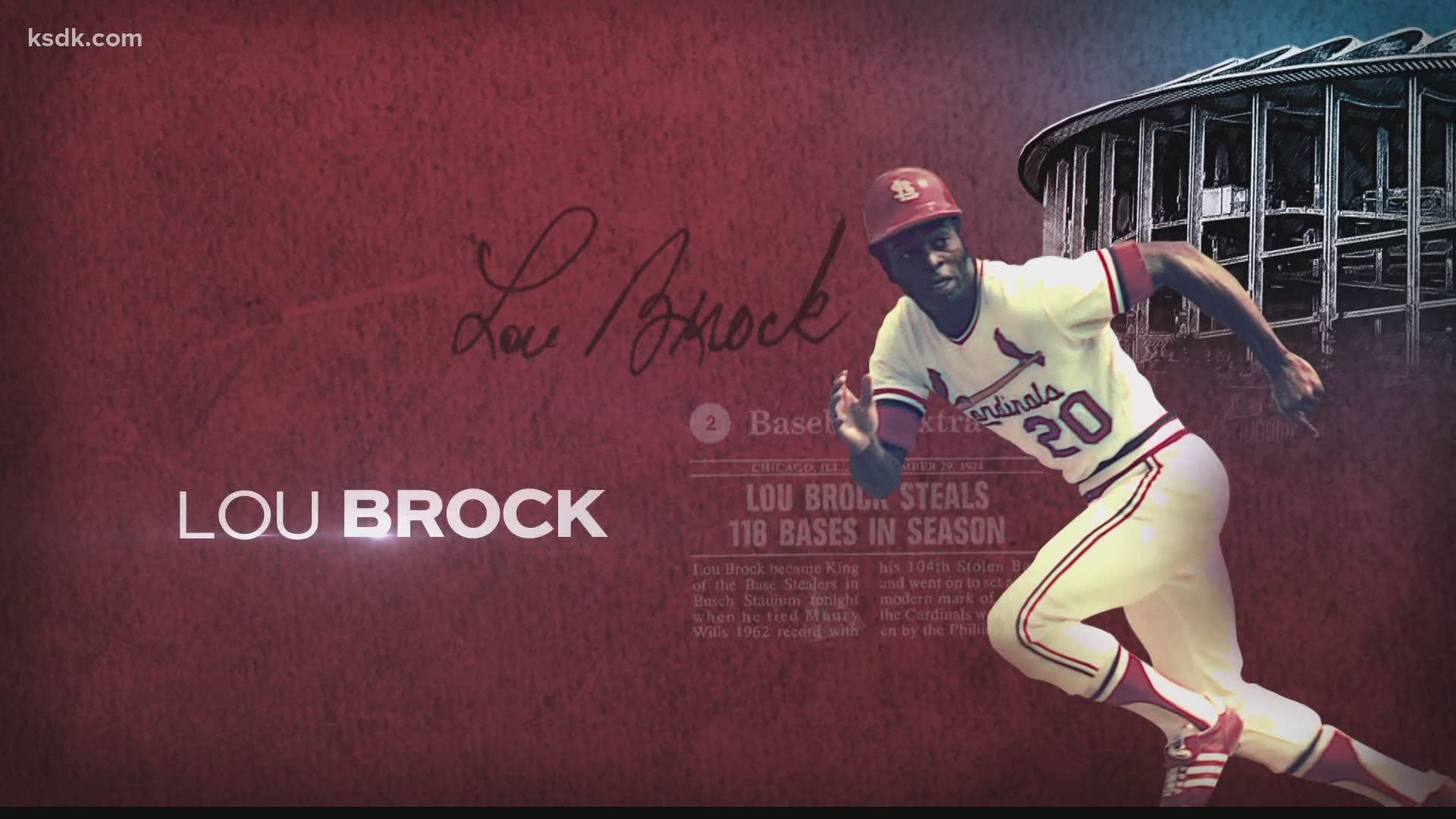

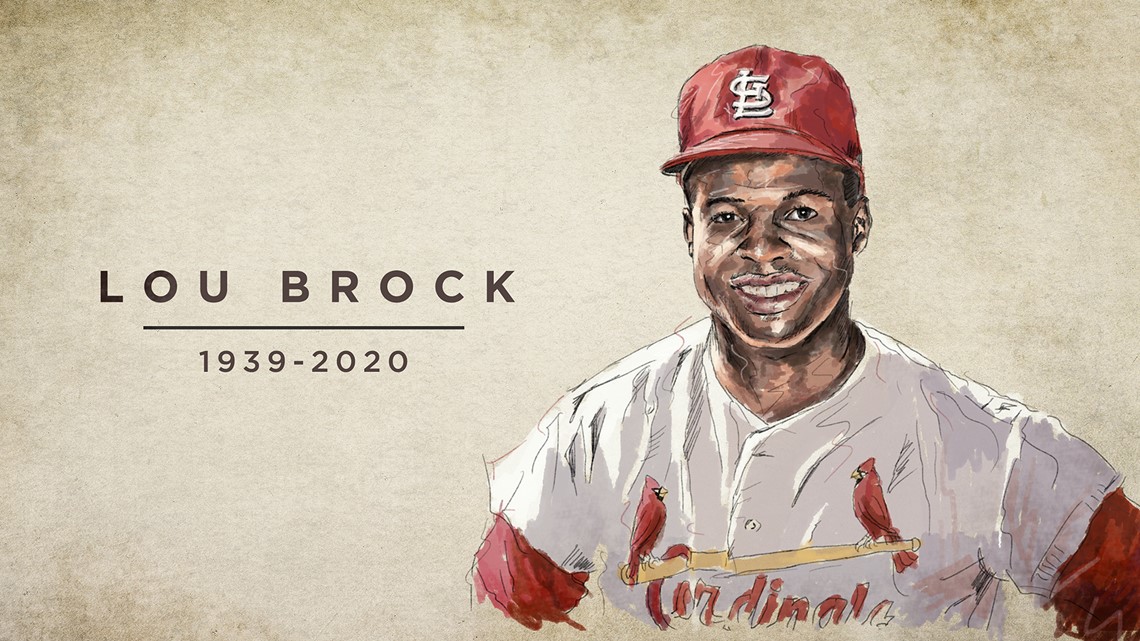

LOU BROCK

Hall of Famer Lou Brock, Cardinals base-stealing icon, dies at 81

September 06, 2020

Hall of Famer Lou Brock, one of baseball's signature leadoff hitters and base stealers who helped the St. Louis Cardinals win three pennants and two World Series titles in the 1960s, died Sunday at 81.

The Cardinals and Chicago Cubs observed a moment of silence in the former outfielder's memory before their game at Wrigley Field.

"Lou Brock was one of the most revered members of the St. Louis Cardinals organization and one of the very best to ever wear the Birds on the Bat,'' Cardinals chairman Bill DeWitt Jr. said in a news release.

"He will be deeply missed and forever remembered.''

Brock retired in 1979 as the single-season and all-time leader in stolen bases -- marks since surpassed by Rickey Henderson. Brock was elected into the Hall of Fame in 1985.

"Lou was an outstanding representative of our national pastime and he will be deeply missed,'' baseball commissioner Rob Manfred said in a release.

Although he showed flashes of his potential with the Cubs, Brock's career took off after he was traded to the Cardinals on June 15, 1964. Acquired in a swap for pitcher Ernie Broglio, Brock became St. Louis' left fielder and hit .348 with 12 homers, 44 RBIs and 33 steals in 103 games.

The Cardinals won the World Series in seven games against the New York Yankees in 1964.

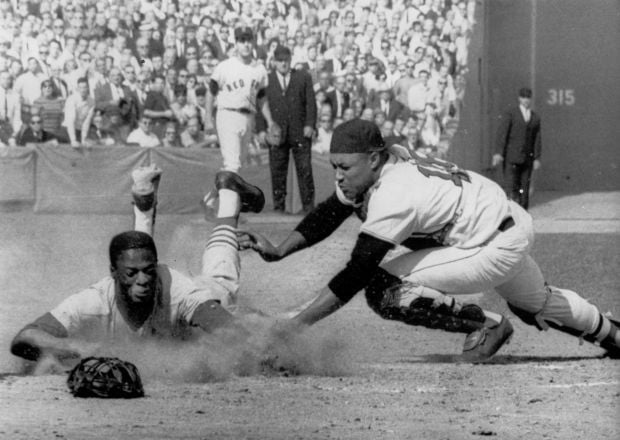

Brock led the team back to the Series in 1967 and 1968. He had 12 hits in 1967, when St. Louis beat the Boston Red Sox in seven games, and had 13 hits a year later, when the Detroit Tigers took the title.

Those two years were part of a 12-season stretch starting in 1965 in which Brock averaged 65 steals and 99 runs scored, with a batting average above .300 in six of those years. He hit 21 homers and stole 52 bases in 1967, making him the first player to hit more than 20 homers with at least 50 steals in a season.

In 1974, Brock surpassed Maury Wills' single-season mark with 118 stolen bases, and he eclipsed Ty Cobb for the career mark in 1977, finishing with 938.

Brock's death came after Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver died Monday. Brock faced Seaver 157 times in his career. That was Brock's most plate appearances against any pitcher, and he was the batter Seaver faced the most, according to ESPN Stats & Information research.

Along with starter Bob Gibson and center fielder Curt Flood, Brock was an anchor for St. Louis as its combination of speed, defense and pitching made it a top team in the '60s and a symbol of the National League's more aggressive style at the time in comparison to the American League.

"There are two things I will remember most about Lou,'' former Cardinals teammate Ted Simmons said in a statement. "First was his vibrant smile. Whenever you were in a room with Lou, you couldn't miss it -- the biggest, brightest, most vibrant smile on earth. The other was that he was surely hurt numerous times, but never once in my life did I know he was playing hurt.''

The El Dorado, Arkansas, native ended his 19-year career with 3,023 hits, 149 homers, 900 RBIs and a .293 average.

Brock was even better in postseason play, batting .391 with four homers, 16 RBIs and 14 steals in 21 World Series games. He had a record-tying 13 hits in the 1968 World Series, and in Game 4, he homered, tripled and doubled as the Cardinals trounced Detroit and 31-game winner Denny McLain 10-1.

Brock never played in another World Series after 1968, but he remained a star for much of the final 11 years of his career.

He was so synonymous with base-stealing that in 1978 he became the first major leaguer to have an award named for him while still active: the Lou Brock Award, for the National League's leader in steals. For Brock, base-stealing was an art form and a kind of warfare. He was among the first players to study films of opposing pitchers and, once on base, relied on skill and psychology.

In his 1976 memoir, "Lou Brock: Stealing is My Game," he explained his success. Take a "modest lead" and "stand perfectly still." The pitcher was obligated to move, if only "to deliver the pitch." "Furthermore, he has two things on his mind: the batter and me," Brock wrote. "I have only one thing in mind -- to steal off him. The very business of disconcerting him is marvelously complex."

Brock closed out his career in 1979 by batting .304, making his sixth All-Star Game appearance and winning the Comeback Player of the Year award. The Cardinals retired his uniform number, 20, and he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1985.

The soft-spoken Brock was determined, no matter the score, and sometimes angered opponents and teammates by stealing even when the Cards were far ahead.

He also made two damaging mistakes that helped cost St. Louis the 1968 World Series.

In Game 5, with the Cards up 3-2 in the top of the fifth and leading the Series 3-1, Brock doubled with one out and seemed certain to score when Julian Javier lined a single to left. But Brock never attempted to slide, and left fielder Willie Horton's strong throw arrived in time for catcher Bill Freehan to tag him out.

The Tigers were among many who cited that moment as a turning point. They rallied to win 5-3 in Game 5 and take the final two in St. Louis. In Game 7, won by Detroit 4-1, Brock made another critical lapse: He was picked off first by the Tigers' Mickey Lolich after singling to lead off the sixth inning, when there was no score.

After his playing career was over, Brock worked as a florist and a commentator for ABC's "Monday Night Baseball" and was a regular for the Cards at spring training. He served as a part-time instructor while remaining an autograph favorite for fans, some of them wearing Brock-a-brellas, a hat with an umbrella top that he designed.

"Our hearts are a little heavy for the passing of Lou, but we know he's in a better place,'' Cardinals manager Mike Shildt said.

Brock was a nominal churchgoer since childhood, but his faith deepened after he endured personal struggles in the 1980s, and he and his third wife, Jacky, became ordained ministers, serving at Abundant Life Fellowship Church in St. Louis. He spoke of having a "Holy Ghost-Filled Alarm Clock'' whenever tempted to resume his previous ways.

"Your old lifestyle's not going away; it's going to be around you for a long time. But you'll find it has no room to enter,'' he once told the Christian Broadcasting Network.

Brock was married three times and had three children, among them Lou Brock Jr., a former NFL cornerback and safety.

The seventh of nine children, Lou Brock was born in Arkansas and grew up in a four-bedroom house in rural Collinston, Louisiana. His introduction to baseball came by accident. Brock spat on a teacher and for punishment had to write a book report about baseball, presumably to teach him about life beyond Collinston.

A star athlete in high school, he was accepted into Southern University on a work-study scholarship and nearly failed but remained with the college when a baseball tryout led to an athletic scholarship. Brock signed with the Cubs as an amateur free agent in 1960, made his major league debut late the following season and was in the starting lineup by 1962.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

The greatness of the late Lou Brock went beyond baseball

Tim KurkjianESPN Senior WriterSept 06, 2020

Lou Brock will be remembered for being part of one the most lopsided trades of all time in Major League Baseball history, the 1964 deal that sent him from the Chicago Cubs as part of a package to the St. Louis Cardinals for veteran pitcher Ernie Broglio. Brock will be remembered for his 3,023 hits -- 2,713 of them for the Cardinals. His having the second-most stolen bases in history and his postseason greatness are things that won't just be remembered in St. Louis or in Cooperstown, where you will find his plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

On top of all of that, I will remember Lou Brock as one of the kindest, sweetest, gentlest men I have ever met.

In 1991, when Rickey Henderson broke Brock's career record for stolen bases, the two became close friends, and together they wrote a short speech that Rickey would read, on the field, immediately after he eclipsed the milestone. Rickey would keep the speech in the pocket of his uniform. But when Henderson stole base No. 939 to set the new standard, he was understandably caught up in the moment. He pulled the third-base bag out of the ground, raised it above his head and announced to the crowd at Oakland Coliseum, "Today, I am the greatest of all time."

Brock could only smile and say, "No, Rickey, the speech?! What about the speech?" He saw Henderson after the game. Brock smiled again and said, "Rickey told me, 'Sorry, I forgot.'"

Brock told that story to my son, Jeff, and me in the golf pro shop in Cooperstown 10 years later. My son was 10 years old. Lou Brock talked to us, mostly to my son, for 20 minutes, not just about baseball -- mostly about life.

"You have a great smile," he told Jeff. "Let everyone see it. A great smile can disarm people like nothing else. Smile as much as you can. We don't smile enough in the world today."

Today is a sad day. But every time I have ever thought of, and will ever think of, Lou Brock, I will smile.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67365768/75569515.jpg.0.jpg) |

| https://www.bleedcubbieblue.com/2020/9/7/21425506/lou-brock-trade-cubs-cardinals-racism |

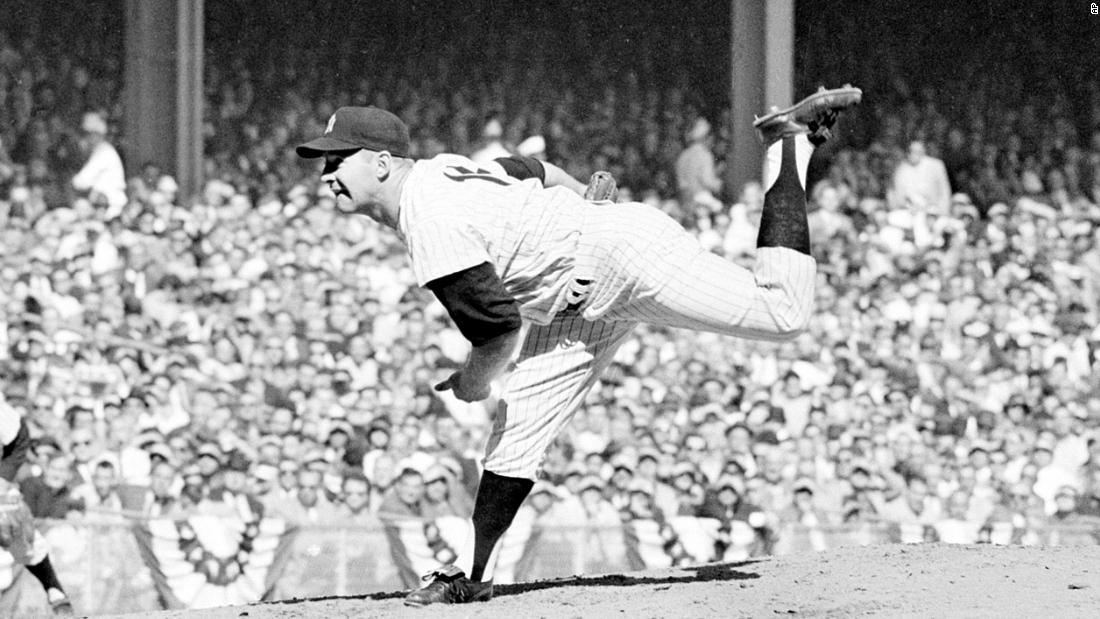

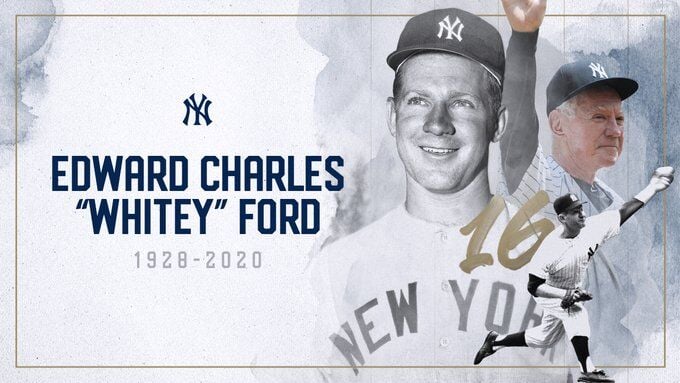

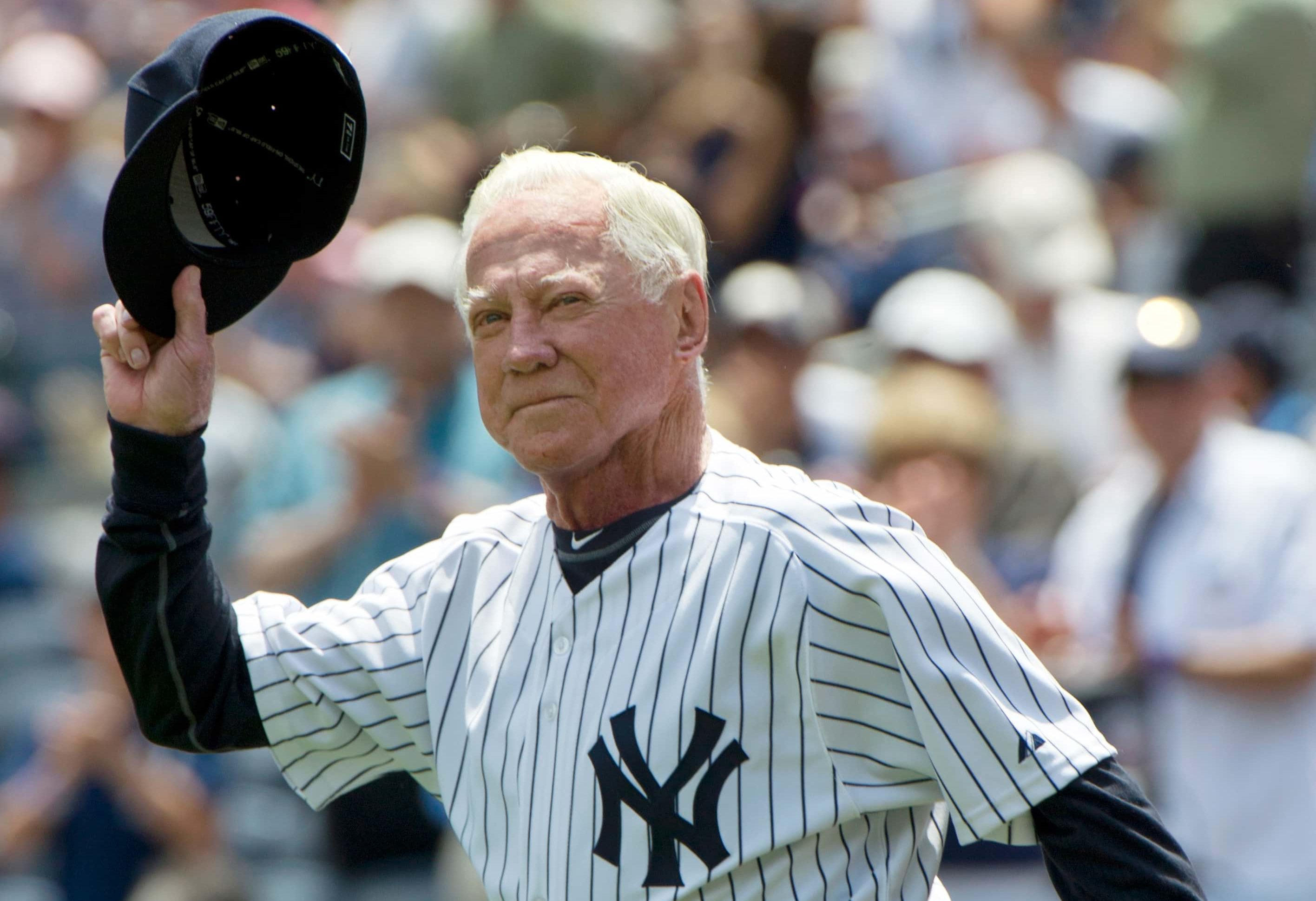

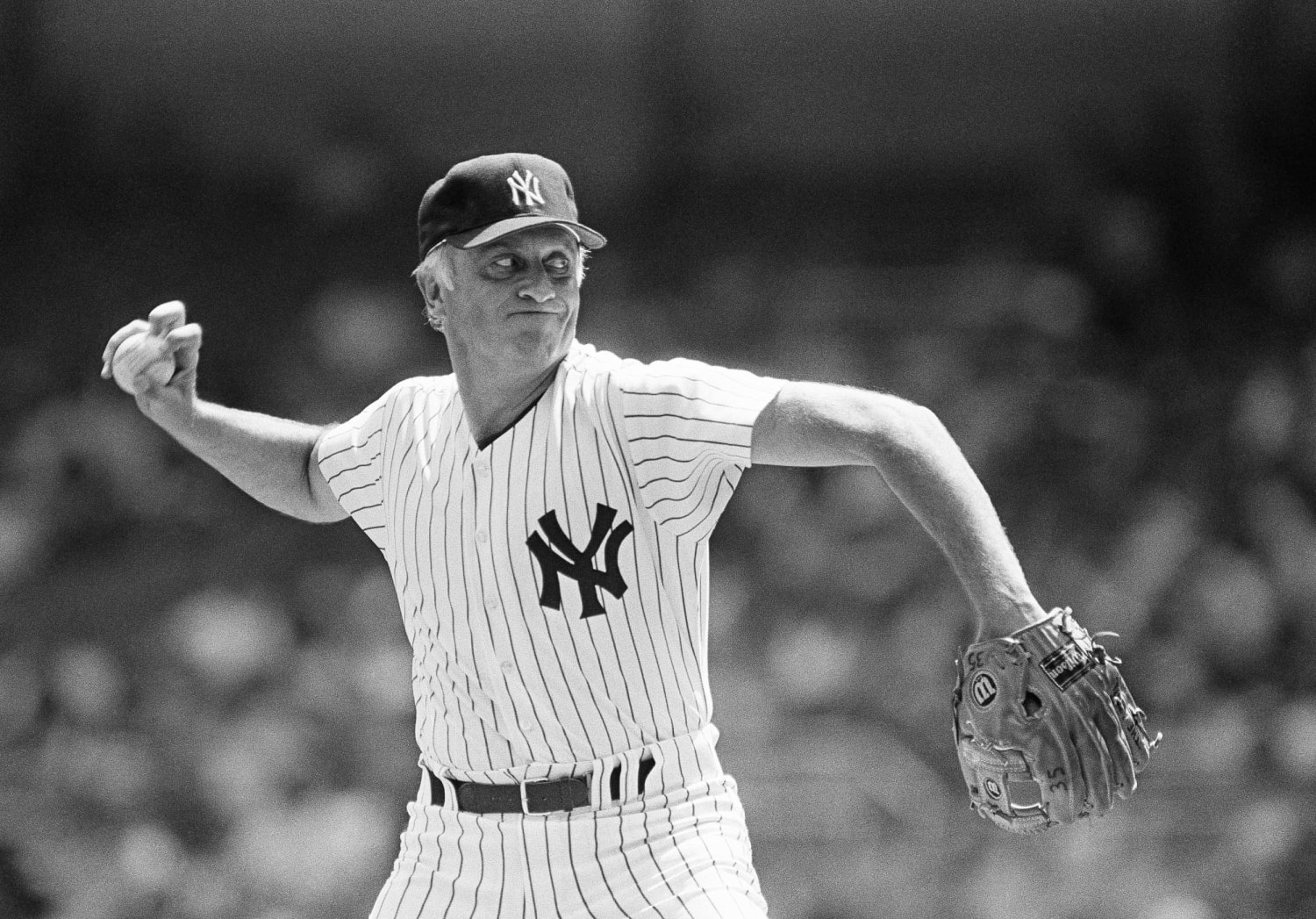

WHITEY FORD

Hall of Famer Whitey Ford, New York Yankees' all-time wins leader, dies at age 91

Whitey Ford, a Hall of Famer for the New York Yankees who won more World Series games than any other pitcher, died at the age of 91, the Yankees announced Friday.

A family member told The Associated Press on Friday that Ford died at his Long Island home Thursday night. Ford had suffered from the effects of Alzheimer's disease in recent years.

Manager Aaron Boone told reporters Friday that Ford died, with his family by his side, while watching the Yankees beat the Tampa Bay Rays in Game 4 of the ALDS.

"I feel like there was some comfort in that," Boone said.

Edward Charles "Whitey" Ford was born on Oct 21, 1928, and grew up in Queens. He made his major league debut for the Yankees in 1950 and spent his entire career with the Bronx Bombers.

In the 1950s, when Pulitzer Prize-winning sports columnist Jim Murray wrote that rooting for the Yankees was like rooting for General Motors or U.S. Steel, there was one man who was "Chairman of the Board."

"Whitey's name and accomplishments are forever stitched into the fabric of baseball's rich history," Yankees owner Hal Steinbrenner said in a statement. "He was a treasure, and one of the greatest of Yankees to ever wear the pinstripes. Beyond the accolades that earned him his rightful spot within the wall of the Hall of Fame, in so many ways he encapsulated the spirit of the Yankees teams he played for and represented for nearly two decades."

The Yankees tweeted a No. 16 patch on their jerseys' left sleeve that they wore in Friday night's Game 5 loss to the Rays.

Ford helped the Yankees win six World Series titles and 11 American League pennants in his 16 seasons. Ford had a career record of 236-106, setting the Yankees' record for victories. His career winning percentage of .690 is the best for any pitcher with at least 300 career decisions. Ford was the Cy Young Award winner in 1961, when he was 25-4, and was a 10-time All-Star.

"Today all of Major League Baseball mourns the loss of Whitey Ford, a New York City native who became a legend for his hometown team. Whitey earned his status as the ace of some of the most memorable teams in our sport's rich history. Beyond the Chairman of the Board's excellence on the mound, he was a distinguished ambassador for our National Pastime throughout his life. I extend my deepest condolences to Whitey's family, his friends and admirers throughout our game, and all fans of the Yankees," commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement.

Ford's status as the best pitcher on the best team was exemplified by his marks in the World Series, where he was chosen as a Game 1 starter eight times. His 10 World Series victories are the most for any pitcher, and he pitched 33⅔ consecutive scoreless innings in World Series play, breaking a record set by Babe Ruth. He also still holds records for World Series starts (22), innings pitched (146) and strikeouts (94).

Ford's best seasons came in 1961 and 1963, in the midst of a stretch of five straight AL pennants for the Yankees, when manager Ralph Houk began using a four-man rotation instead of five. Ford led the league in victories with 25 in 1961, won the Cy Young Award and was the World Series MVP after winning two more games against Cincinnati. In 1963, he went 24-7, again leading the league in wins. Eight of his victories that season came in June. He also led the AL in earned run average in 1956 (2.47) and 1958 (2.01).

"If you were a betting man, and if he was out there pitching for you, you'd figure it was your day,'' former teammate and World Series MVP Bobby Richardson told The Associated Press on Friday.

Ford and Mickey Mantle were the icons for their edition of the Yankees dynasty and, fittingly, they went into the Hall of Fame together in 1974. Ford's No. 16 was retired by the Yankees that year.

Ford often called his Hall of Fame election the highlight of his career, made more meaningful because he was inducted with Mantle, who died in 1995.

"It never was anything I imagined was possible or anything I dared dream about when I was a kid growing up on the sidewalks of New York,'' he wrote in his autobiography. "I never really thought I would make it as a kid because I always was too small.''

Ford's death is the latest of a number of baseball greats in 2020. Al Kaline, Tom Seaver, Lou Brock and Bob Gibson also died this year.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

BOB GIBSON

Hall of Famer Bob Gibson, St. Louis Cardinals ace, dies at 84

Baseball Hall of Famer Bob Gibson died Friday at age 84, the St. Louis Cardinals confirmed to ESPN.

Gibson, who was born in Omaha, Nebraska, played all of his 17 MLB seasons with the Cardinals from 1959 through 1975.

He announced in July 2019 that he had pancreatic cancer.

The nine-time All-Star and two-time World Series champion earned 251 wins, struck out 3,117 and had a 2.91 ERA and was known as a fierce competitor who rarely smiled.

The two-time Cy Young Award winner was named the World Series MVP in the Cardinals' 1964 and 1967 championship seasons. He was the National League MVP in 1968.

At his peak, Gibson might have been the most talented all-around starter in history, a nine-time Gold Glove winner who roamed wide to snatch up grounders despite a fierce, sweeping delivery that drove him to the first-base side of the mound and a strong hitter who twice hit five home runs in a season and batted .303 in 1970, when he also won his second Cy Young.

Averaging 19 wins per year from 1963 through 1972, he finished 251-174 and was only the second pitcher to reach 3,000 strikeouts. He didn't throw as hard as Sandy Koufax or from as many angles as Juan Marichal, but batters never forgot how he glared at them (or squinted, because he was nearsighted) as if settling an ancient score.

In 1968, "The Year of the Pitcher," Gibson made a case for one of the greatest seasons ever produced by a starter. He went 22-9 with a 1.12 ERA and 13 shutouts, leading to the pitcher's mound being lowered from 15 to 10 inches. Gibson completed 28 of his 34 starts.

"I was pissed," Gibson later remarked about the rule change brought on by his dominance.

Even with the change, Gibson remained a top pitcher for several years and in 1971 threw his only no-hitter, against Pittsburgh.

"This is a very sad day for all of Baseball," MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. "Bob Gibson produced one of the most decorated pitching careers in history with his intelligence, athleticism, durability and toughness. One of only three players to be a two-time MVP of the World Series, this legend of October will always be remembered as one of our sport's fiercest competitors. His performance in 1968 with the Club he represented all his life, the St. Louis Cardinals, is on the short list of the best pitching seasons ever.

"Bob was a loyal friend to many people throughout the National Pastime, and he will be deeply missed. On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my deepest condolences to Bob's family, friends, Cardinals fans, and all those who respected one of the greatest pitchers who ever lived."

Gibson's death came on the 52nd anniversary of perhaps his most overpowering performance, when he struck out a World Series-record 17 batters in Game 1 of the 1968 Fall Classic against the Detroit Tigers.

"It was just so hard to beat him," Chicago Cubs slugger and fellow Hall of Famer Billy Williams once said about Gibson. "One year, Roberto Clemente hit a line drive that hit him right in the shin. He pitched another five, six innings to finish the game, then it turned out he had a broken leg."

Jack Flaherty, who was the starting and losing pitcher for the Cardinals in Friday's season-ending loss to the San Diego Padres, shared his condolences on Twitter.

St. Louis catcher Yadier Molina, who has played his entire career with the Cardinals, said the news of Gibson's death put Friday's defeat in perspective.

"It's kind of hard losing a legend. You can lose a game, but when you lose a guy like Bob Gibson, just hard," Molina said. "Bob was funny, smart, he brought a lot of energy. When he talked, you listened. It was good to have him around every year. We lose a game, we lose a series [Friday], but the tough thing is we lost one great man."

Gibson's tenacity set him apart from many of his peers. He snubbed opposing players and sometimes teammates who dared speak to him on a day he was pitching, and he didn't even spare his own family.

"I've played a couple of hundred games of tic-tac-toe with my little daughter, and she hasn't beaten me yet," he once told The New Yorker's Roger Angell. "I've always had to win. I've got to win."

Equally disciplined and impatient, Gibson worked so quickly that broadcaster Vin Scully joked that he pitched as if his car were double-parked. He had no use for advice, scowling whenever catcher Tim McCarver or anyone else thought of visiting the mound.

"The only thing you know about pitching is you can't hit it," Gibson was known to say.

His concentration was such that he seemed unaware he was on his way to a World Series single-game strikeout record (surpassing Koufax's 15) until McCarver convinced him to look at the scoreboard.

During the regular season, Gibson struck out more than 200 batters nine times and led the National League in shutouts four times, finishing with 56 in his career. His 13 shutouts in 1968 led McCarver to call Gibson "the luckiest pitcher I ever saw. He always pitches when the other team doesn't score any runs."

He was, somehow, even greater in the postseason, finishing 7-2 with a 1.89 ERA and 92 strikeouts in 81 innings. Despite dominating the Tigers in the 1968 Series opener, that year ended with a Game 7 loss -- hurt by a rare misplay from star center fielder Curt Flood.

Gibson's 1.12 ERA in that regular season was the third lowest for any starting pitcher since 1900 and by far the best for any starter in the post-dead ball era, which began in the 1920s.

Signed by the Cardinals as an amateur free agent in 1957, Gibson had early trouble with his control, a problem solved by developing one of baseball's greatest sliders, along with a curve to go with his hard fastball. He knew how to throw strikes and how to aim elsewhere when batters stood too close to the plate.

Hank Aaron once counseled Atlanta Braves teammate Dusty Baker about Gibson.

"Don't dig in against Bob Gibson; he'll knock you down," Aaron said, according to The Boston Globe. "He'd knock down his own grandmother if she dared to challenge him. Don't stare at him, don't smile at him, don't talk to him. He doesn't like it. If you happen to hit a home run, don't run too slow, don't run too fast. If you happen to want to celebrate, get in the tunnel first. And if he hits you, don't charge the mound, because he's a Gold Glove boxer."

Only the second Black player, after Don Newcombe, to win the Cy Young Award, Gibson was an inspiration while insisting otherwise. He would describe himself as a "blunt, stubborn Black man" who scorned the idea he was anyone's role model and once posted a sign over his locker reading, "I'm not prejudiced. I hate everybody."

But he was proud of the Cardinals' racial diversity and teamwork, a powerful symbol during the civil rights movement, and his role in ensuring that players did not live in segregated housing during the season.

He was close to McCarver, a Tennessean who would credit Gibson with challenging his own prejudices, and the acknowledged leader of a club that featured whites (McCarver, Mike Shannon, Roger Maris), Blacks (Gibson, Flood, Lou Brock) and Hispanics (Orlando Cepeda, Julian Javier).

"Our team, as a whole, had no tolerance for ethnic or racial disrespect," Gibson wrote in "Pitch by Pitch," published in 2015. "We'd talk about it openly and in no uncertain terms. In our clubhouse, nobody got a free pass."

Flaherty, who is Black, grew close to Gibson in recent years. The right-handers would often talk, the 24-year-old Flaherty soaking up advice from the great who wore No. 45.

"That one hurts," Flaherty said. "He's a legend, first and foremost, somebody who I was lucky enough to learn from. You don't get the opportunity to learn from somebody of that caliber and somebody who was that good very often."

"I had been kept up on his health and where he was at. I was really hoping it wasn't going to be today. I was going to wear his jersey today to the field but decided against it,"

Jim Palmer, a contemporary of Gibson's and a Hall of Famer for the Baltimore Orioles, shared his thoughts on Twitter.

"Dave Johnson would sometimes run in from 2nd base and say give them the Bob Gibson! I'd say, there is only 1 Bob Gibson," Palmer wrote. "Wasn't that the truth. Talented, competitive, a warrior on the hill! So glad I got to know him. Will dearly miss him."

Gibson -- who went by the nickname "Hoot" after cowboy and silent movie star Hoot Gibson -- was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility, in 1981. He was inducted into the team's hall of fame in 2014.

Among his other honors, Gibson was ranked No. 31 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players and was elected to the MLB All-Century Team in 1999.

After retiring, Gibson was an "attitude coach" for Joe Torre, his former teammate, with the New York Mets then followed Torre to the Braves, where Gibson was pitching coach. Before that, he was a backup color analyst for ABC's Monday Night Baseball in 1976, and briefly was a color commentator for the New York Nets of the American Basketball Association.

In 1990, Gibson was a color commentator for baseball games on ESPN, and in 1995, he again worked with Torre as a pitching coach, this time with the Cardinals.

Gibson died less than a month after the death of a longtime teammate, Hall of Fame outfielder Lou Brock. Another pitching great from his era, Tom Seaver, died in late August.

Information from The Associated Press was used in this report.

Tim KurkjianESPN Senior Writer

Oct. 2, 2020

In his day, St. Louis Cardinals great Bob Gibson was feared like no other pitcher

In 2006, less than an hour after Tony La Russa had won his first World Series as the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, he was greeted in the hallway at Busch Stadium by an iconic figure.

"Bob Gibson just shook my hand," said La Russa, who had won a World Series with Oakland, and won nearly 2,500 games by that time, yet he was glowing, in awe of what had just happened. "I just got welcomed to the club by Bob Gibson."

That's the reverence paid to Bob Gibson, not just in St. Louis, but across major league baseball: Something, or someone, becomes official when endorsed by Bob Gibson. He was one of the greatest pitchers of all time, he was arguably the greatest athlete ever to pitch in the big leagues, and when it came to competing, no one was more ferocious than Gibson.

Gibson, who announced in July 2019 that he had pancreatic cancer, died Friday at age 84.

"I loved facing him because he wanted to win so much," said Frank Robinson, a fellow Hall of Famer. "If I won the battle against him, I knew that I had beaten the absolute best."

Gibson went 251-174 with a 2.91 ERA for the Cardinals from 1959 to 1975, making him, without a doubt, the greatest pitcher in Cardinals history, and after Stan Musial, the greatest player in Cardinals history. Gibson won two Cy Young Awards, in 1968 and 1970, the first Cardinal to win the Cy Young, the only Cardinal to win the award twice.

In his 1968 season, he posted a 1.12 ERA, the lowest by any pitcher in the live ball era (since 1920), and the second lowest to the Cubs' Mordecai "Three Finger" Brown (1.04 in 1906) in the modern era (since 1900). That season, Gibson threw 47 consecutive scoreless innings, which, at the time, was the third-longest streak in history. He completed 28 out of 34 games, and he was removed for a pinch hitter eight times: meaning, he was not replaced on the mound, in mid-inning, by another pitcher all season. He threw 13 shutouts, he had 56 in his career, nearly as many as Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine had combined.

Gibson made nine All-Star teams.

"I hated the All-Star Game," Gibson said years after retirement. "I hated having to talk to guys that I spent the rest of the season trying to kick their ass. They were the enemy to me."

"Gibby was no fun at the All-Star Game," Willie Mays said, smiling. "He didn't talk to anyone."

"No pitcher I faced competed like Gibson," Hank Aaron said. "He hated you when he pitched."

Gibson especially hated hitters, it seems, in the postseason. He made nine starts, all in the World Series, and completed eight, went 7-2 with a 1.89 ERA. In 81 innings, he gave up 55 hits, walked 17 and struck out 92.

In Game 7 of the 1964 World Series, he pitched a complete game to beat Mickey Mantle and the Yankees.

In 1967 against the Red Sox, Gibson won Games 1, 4 and 7, making him the first pitcher to record a complete-game victory in a Game 7 of two World Series. In Game 1 of the 1968 Series against the Tigers, Gibson struck out 17, which remains a postseason record.

"We had no chance," former Tiger Norm Cash said. "That was the best stuff I had ever seen."

Gibson was the second pitcher -- joining the great Walter Johnson -- in major league history to reach 3,000 strikeouts, a distinction Gibson held at the time of his retirement in 1975. The Cardinals retired Gibson's uniform No. 45 before his final season had even ended.

"The best I ever played with," ex-teammate Mike Shannon said. "There was no one like Gibby."

Gibson was perhaps as good an athlete as has ever pitched in the major leagues. He was a great hitter, with 24 home runs, a mark only seven pitchers surpassed in the game's history. In 1970, he joined a select group of pitchers who won 20 games in a season in which he batted .300. Gibson was also one of the best fielding pitchers of all time, winning nine Gold Gloves.

Gibson was an all-state basketball player in high school in Omaha, Nebraska, then averaged 22 points a game his junior year at Creighton University. He signed with the Cardinals in 1957 but delayed his baseball career so he could play a year for the Harlem Globetrotters.

"Playing basketball made me a better baseball player," Gibson said. "It helped with my footwork, my hand-eye coordination, my stamina. I loved basketball just like I loved baseball."

And he showed that love by competing, by overpowering hitters, by intimidating hitters.

"If you showed him up in any way on the field," Robinson said, "you were going down."

"I was told by Hank Aaron never to mess with Bob Gibson," Astros manager Dusty Baker said. "I was told never to stare at him, or talk to him, or smile at him. And if he hit you with a pitch, I was told never to charge the mound because he would beat your ass."

Tim McCarver caught Gibson for many years, becoming close friends with him. And yet, when McCarver went to the mound to talk to Gibson, he wasn't always given a kindly welcome. McCarver famously said that Gibson was particularly ornery during one trip to the mound, and said to McCarver, "The only thing you know about pitching is you can't hit it."

Gibson retired after the 1975 season in part because a knee injury took away his greatness, and he wasn't about to pitch to an ERA above 5.00. In his final seasons, Gibson had a brief confrontation with Pirates third baseman Richie Hebner, but Gibson never got to finish it on the field. In retirement, he saw Hebner on an elevator and, only half-joking, went after him.

That was Bob Gibson, a fighter, a ferocious competitor, to the end.

PHIL NIEKRO

Hall of Fame pitcher Phil Niekro, famous for signature knuckleball, dies at 81

Phil Niekro, a pitcher who used his signature knuckleball to fool generations of hitters and craft a Hall of Fame career, died Saturday night in his sleep after a long battle with cancer, the Atlanta Braves announced Sunday. He was 81.

Niekro, inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1997, was one of baseball's most prolific and durable pitchers, using his "butterfly" pitch to win 318 games in a career that spanned 24 seasons, including 21 with the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves.

"We are heartbroken on the passing of our treasured friend, Phil Niekro," the Braves said in a statement. "Knucksie was woven into the Braves fabric, first in Milwaukee and then in Atlanta. Phil baffled batters on the field and later was always the first to join in our community activities. It was during those community and fan activities where he would communicate with fans as if they were long lost friends.

"He was a constant presence over the years, in our clubhouse, our alumni activities and throughout Braves Country and we will forever be grateful for having him be such an important part of our organization.

"Our thoughts and prayers are with his wife Nancy, sons Philip, John and Michael and his two grandchildren Chase and Emma."

Niekro joined Lou Brock, Whitey Ford, Bob Gibson, Al Kaline, Joe Morgan and Tom Seaver as Hall of Famers who died in 2020 -- the most ever to pass away in a calendar year, according to Hall of Fame spokesman Jon Shestakofsky.

As with many knuckleball pitchers, age proved no barrier to Niekro. He amassed 121 victories after he turned 40 -- a major league record -- and pitched until he was 48. By the end of 1987, his final season, Niekro ranked 10th among major leaguers in number of seasons played. Only Cy Young, "Pud" Galvin and Walter Johnson pitched more innings than Niekro's 5,404. No pitcher since the dead ball era spent more time on a major league mound.

"Phil Niekro was one of the most distinctive and memorable pitchers of his generation," MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. "In the last century, no pitcher threw more than Phil's 5,404 innings. His knuckleball led him to five All-Star selections, three 20-win seasons for the Atlanta Braves, the 300-win club, and ultimately, to Cooperstown.

"But even more than his signature pitch and trademark durability, Phil will be remembered as one of our game's most genial people. He always represented his sport extraordinarily well, and he will be deeply missed. On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my condolences to Phil's family, friends and the many fans he earned throughout his life in our National Pastime."

Dale Murphy, who won two straight National League MVP awards as a teammate of Niekro's, was among those who mourned his death.

"Knucksie was one of a kind,'' Murphy wrote on Twitter. "Friend, teammate, father and husband. Our hearts go out to Nancy Niekro, the kids and grandkids. So thankful for our memories and time together. We'll miss you, Knucksie.''

The symbol of both the success and longevity of Niekro's career was the knuckleball, that whimsical floater that baffles not only hitters and catchers but also the pitchers who never really know how the rotationless pitch will dance toward the plate.

Niekro was the king of the knuckleballers, ranking first in victories and strikeouts (3,342). Tom Candiotti, a notable knuckler in his time and a teammate of Niekro's with the 1986 Cleveland Indians, said that talking to Knucksie was "like talking to Thomas Edison about light bulbs."

If staying in the majors could be owed to the knuckler, the same factor might also explain Niekro's initial difficulty in reaching the big leagues. Perplexed catchers and managers wary of passed balls and wild pitches were reasons often cited for Niekro's extended stay in the Braves' minor league system. Signed in 1958, he didn't break through for good for nearly a decade. Yet the knuckler was all Niekro had, all he believed in.

"I never knew how to throw a fastball, never learned how to throw a curveball, a slider, split-finger, whatever they're throwing nowadays," he said. "I was a one-pitch pitcher."

First called up by Milwaukee in 1964, Niekro seesawed between the majors and minors, a pitcher struggling to find a niche and willing catchers. He found both in 1967, when he was united with Bob Uecker, a veteran reserve backstop with many quips and sage advice.

"Ueck told me if I was ever going to be a winner to throw the knuckleball at all times and he would try to catch it," Niekro said. "I led the league in ERA [1.87], and he led the league in passed balls."

Uecker acknowledged he did a lot of chasing.

"Catching Niekro's knuckleball was great," said Uecker, now a Hall of Fame announcer. "I got to meet a lot of important people. They all sit behind home plate."

By 1969, Niekro was an All-Star. His 23 victories that season earned him second place in the National League Cy Young Award vote. He would go on for two more decades living inside hitters' heads.

"There aren't many hitters who like facing knuckleball pitchers," Niekro said. "They may not be intimidated by them, but they sure are thinking about them before they go into the box."

"Trying to hit Phil Niekro is like trying to eat Jell-O with chopsticks," former New York Yankees All-Star outfielder Bobby Murcer said.

"He simply destroys your timing with that knuckleball," Hall of Famer Ernie Banks said. "It comes flying in there dipping and hopping like crazy, and you just can't hit it."

"It actually giggles at you as it goes by," former outfielder Rick Monday said.

Niekro, born in Blaine, Ohio, on April 1, 1939, was the proud scion of a family dynasty of sorts. Phil Niekro Sr., a laborer and part-time semipro pitcher, had mastered the knuckler after an arm injury threatened to end his playing days. He would teach his sons, Phil Jr. and Joe, the pitch when they were youngsters. Phil and Joe, known as "Knucksie" and "Little Knucksie," respectively, learned well, going on to pitch a total of 46 major league seasons, earn six All-Star Game berths and, in perhaps their proudest achievement, combine for 539 victories.

Their win total still stands as a major league record for siblings, as they surpassed another brother combination featuring a Hall of Famer: Gaylord and Jim Perry (529 wins combined).

Though Phil and Joe Niekro did twice team together, with the 1973-74 Braves and the 1985 Yankees, the two self-declared best friends were more often friendly rivals. In 1979, Phil, pitching for the Braves, and Joe, for the Astros, tied for the most victories in the National League, with 21 each. They clawed against each other as mound opponents, with Joe defeating his big brother 5-4 in their careers. That edge was made possible by a game-winning home run Phil gave up to Joe, the only homer Joe hit in his 22-year career.

When Phil Niekro won his 300th game, Joe was at his side, and it was arguably the most unique victory of the elder brother's career. It was Oct. 6, 1985, the final day of the season. The Yankees had fallen short of the postseason the day before with a loss in Toronto. In the finale, manager Billy Martin handed pitching coach duties to Joe Niekro and the ball to Phil Niekro. Phil, trying for a fifth time to win No. 300, entered the bottom of the ninth having shut out the Jays on curveballs, slip pitches, fastballs and screwballs -- everything but a knuckleball.

He would say later that he wanted to prove he was a pitcher, not just a knuckleballer. Then sentiment finally took over with two out in the ninth. Facing Jeff Burroughs, an old friend and former Braves teammate, Niekro threw four pitches -- the final three knucklers. Burroughs struck out, giving the Yankees an 8-0 victory and Niekro his milestone.

"I figured if there's any way I'm going to win my 300th game by striking the guy out, I was going to do it with the pitch that won the first game for me," Niekro said.

Phil Niekro's playing days ended in 1987, but he would don a uniform one more time, as manager of the women's barnstorming Colorado Silver Bullets (1994-97). His pitching coach? Joe Niekro.

Phil Niekro was preceded in death by Joe Niekro, who suffered a fatal brain aneurysm in 2006. He is survived by his wife, Nancy, sons Philip, John and Michael, and two grandchildren, Chase and Emma.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

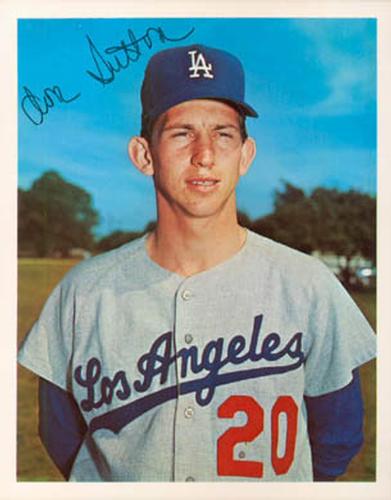

DON SUTTON

https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/30743861/hall-fame-pitcher-don-sutton-dies-75

Hall of Fame pitcher Don Sutton dies at 75

Don Sutton, the longtime Los Angeles Dodgers right-hander who won over 300 games in his Hall of Fame career, died Monday night, his son Daron announced on social media.

The Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, said Don Sutton died of cancer at his home in Rancho Mirage, California. He was 75.

"Saddened to share that my dad passed away in his sleep last night," Daron Sutton wrote on Twitter. "He worked as hard as anyone I've ever known and he treated those he encountered with great respect...and he took me to work a lot. For all these things, I am very grateful. Rest In Peace."

Sutton's career began and ended with the Dodgers, with whom he spent 16 of his 23 seasons -- spanning from 1966 to 1980 and returning for a final tour in 1988. He was a four-time All-Star with a career 324-256 mark and a 3.26 ERA. His 324 wins rank 14th in major league history.

"Today we lost a great ballplayer, a great broadcaster and, most importantly, a great person," Dodgers president and CEO Stan Kasten said in a statement. "Don left an indelible mark on the Dodger franchise during his 16 seasons in Los Angeles and many of his records continue to stand to this day. I was privileged to have worked with Don in both Atlanta and Washington, and will always cherish our time spent together."

Sutton also pitched for the Houston Astros, Milwaukee Brewers, Oakland Athletics and Los Angeles Angels.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998.

"Don Sutton was one of our game's most consistent winning pitchers across his decorated 23-year career," MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement, calling Sutton "a model of durability on the mound."

"Throughout his career, Don represented our game with great class, and many will remember his excitement during his trips to Cooperstown," Manfred continued. "On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my deepest condolences to Don's family, friends and the many fans he earned throughout a memorable life in our National Pastime."

The durable Sutton never missed a turn in the rotation in 756 big league starts. Only Cy Young and Nolan Ryan made more starts than Sutton, who never landed on the injured list. A master of changing speeds and pitch location, Sutton recorded just one 20-win season, but he earned 10 or more wins in every season except 1983 and 1988. Of his victories, 58 were shutouts, five were one-hitters and 10 were two-hitters. The right-hander is seventh on the career strikeout list with 3,574.

He ranks third all-time in games started and seventh in innings pitched (5,282⅓). He worked at least 200 innings in 20 of his first 21 seasons, with only the shortened 1981 season interrupting his streak.

Born Donald Howard Sutton on April 2, 1945, in Clio, Alabama, he was the son of sharecroppers. The family moved to northern Florida, where Sutton was a three-sport star in high school who showed an affinity for baseball as a youngster. He played the sport in junior college before the Dodgers signed him as a free agent in September 1964, months before the first MLB draft.

After going 23-7 during one season in the minors, Sutton won a spot in the Dodgers' rotation in 1966. He made his big league debut for the defending World Series champions on April 14, 1966, and earned his first victory four days later.

Sutton immediately found himself in a rotation with Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Claude Osteen as the fourth starter. Sutton recorded 209 strikeouts that season, the highest total for a rookie since 1911. He helped the team win the National League pennant but didn't pitch in the World Series as the Dodgers were swept in four games by the Baltimore Orioles. He also led the Dodgers to NL pennants in 1974, 1977 and 1978.

Sutton left the team as a free agent in 1980 and signed with Houston. A trade in 1982 sent Sutton to Milwaukee, where he pitched the Brewers to their first American League pennant. He worked for his sixth postseason team in 1986 with the AL West champion Angels and then returned to the Dodgers in 1988, retiring before the end of a season that saw them win the World Series.

After his playing career, Sutton served as an analyst for the Atlanta Braves for 28 seasons, calling games on both television and radio.

"We are deeply saddened by the passing of our dear friend, Don Sutton," the Braves said in a statement. "A generation of Braves fans came to know his voice. ... Don was as feared on the mound as he was beloved in the booth. A 300-game winner who was a four-time All-Star, Don brought an unmatched knowledge of the game and his sharp wit to his calls. But despite all the success, Don never lost his generous character or humble personality."

He joined the Braves in 1989 when they were one of baseball's worst teams but had developed a national following through TBS and its trio of broadcasters: Skip Caray, Pete Van Wieren and Ernie Johnson Sr.

Sutton was part of the soundtrack for Atlanta's worst-to-first season in 1991, its dominating run of 14 straight division titles, and the 1995 World Series championship. He called Braves games on television and radio for 28 of 30 seasons, interrupted only by his move to the Washington Nationals in 2007. He returned to the Braves in 2009 and continued to broadcast games through the 2018 season.

"Don Sutton's brilliance on the field, and his lasting commitment to the game that he so loved, carried through to his time as a member of the Hall of Fame," Jane Forbes Clark, chairman of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, said in a statement. "I know how much he treasured his moments in Cooperstown, just as we treasured our special moments with him. We share our deepest condolences with his wife, Mary, and his family."

Sutton's death comes on the heels of seven Hall of Famers dying in 2020, the most sitting members of Cooperstown to die in a calendar year. They were Lou Brock, Whitey Ford, Bob Gibson, Al Kaline, Joe Morgan, Phil Niekro and Tom Seaver.

Sutton pitched for Dodgers Hall of Fame manager Tommy Lasorda, who died on Jan. 7.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2101.31 -10:10

- Days ago = 2039 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.