A Sense of Doubt blog post #2174 - Hammerin' Hank Aaron - RIP

I don't have much to write here.

Sad. Aaron is just one year older than my Dad.

Both are heroes of mine.

FROM MY TWITTER:

The older I get, the more my childhood heroes pass on. Goodbye Hammerin' Hank. Thank you for being AWESOME. #HammerinHank #HenryAaronRIP #BaseballLegends

https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/30759123/long-home-run-king-hank-aaron-dies-86

Longtime MLB home run king Hank Aaron dies at 86

Remembering Hank Aaron, one of the greatest MLB players ever

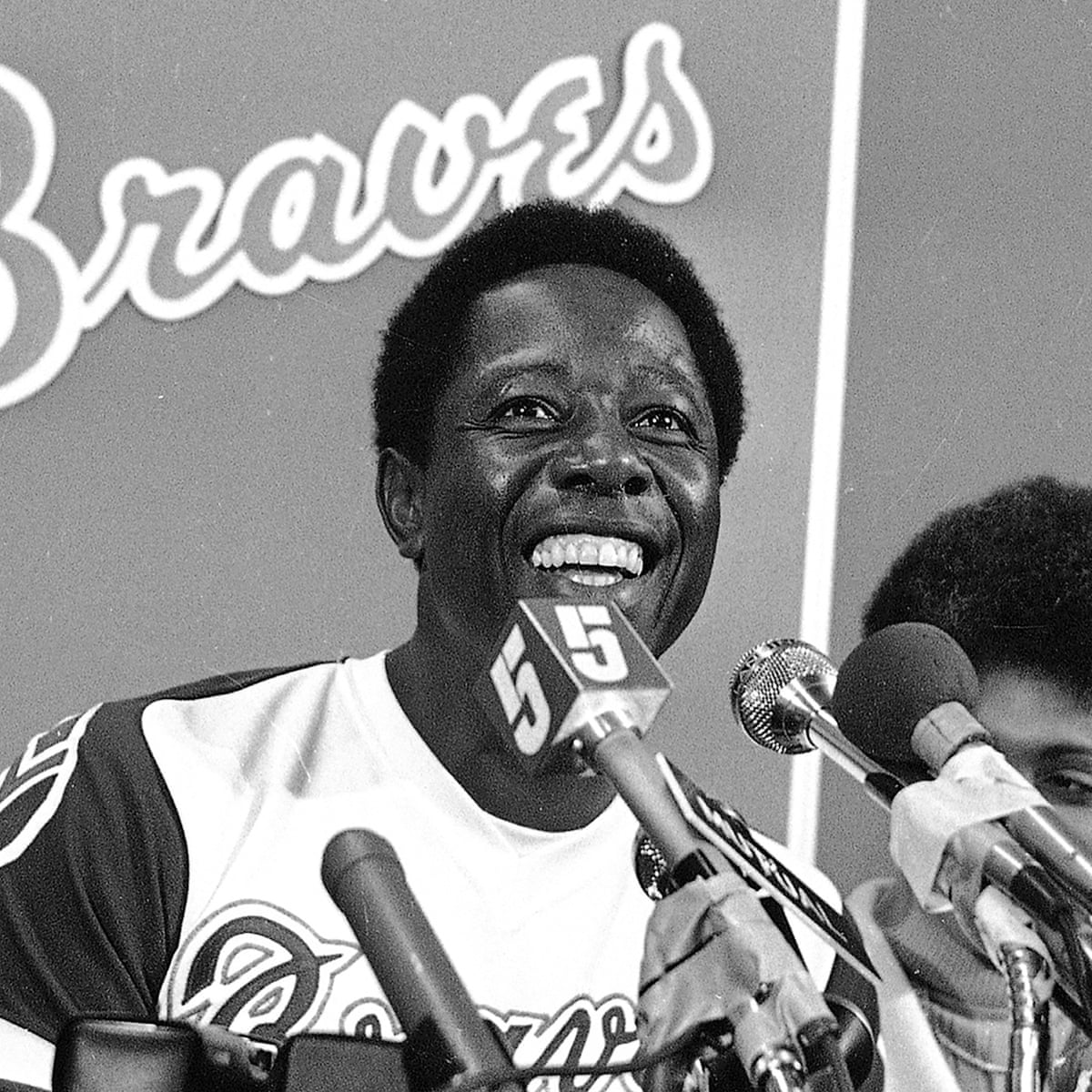

MLB - MLB is devastated by the passing of Hammerin’ Hank Aaron, one of the greatest players and people in the history of our game. He was 86.

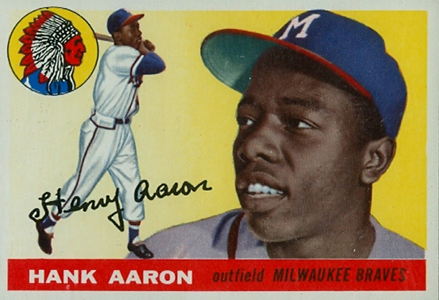

Henry Louis "Hank" Aaron, the Hall of Fame slugger whose 755 career home runs long stood as baseball's golden mark, has died. He was 86.

"Our family is heartbroken to hear the news of Hank Aaron's passing," Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp said in a statement on behalf of the Aaron family. "Hank Aaron was an American icon and one of Georgia's greatest legends. His life and career made history, and his influence was felt not only in the world of sports, but far beyond -- through his important work to advance civil rights and create a more equal, just society. We ask all Georgians to join us in praying for his fans, family, and loved ones as we remember Hammerin' Hank's incredible legacy."

The Atlanta Braves said in a release that Aaron died peacefully in his sleep.

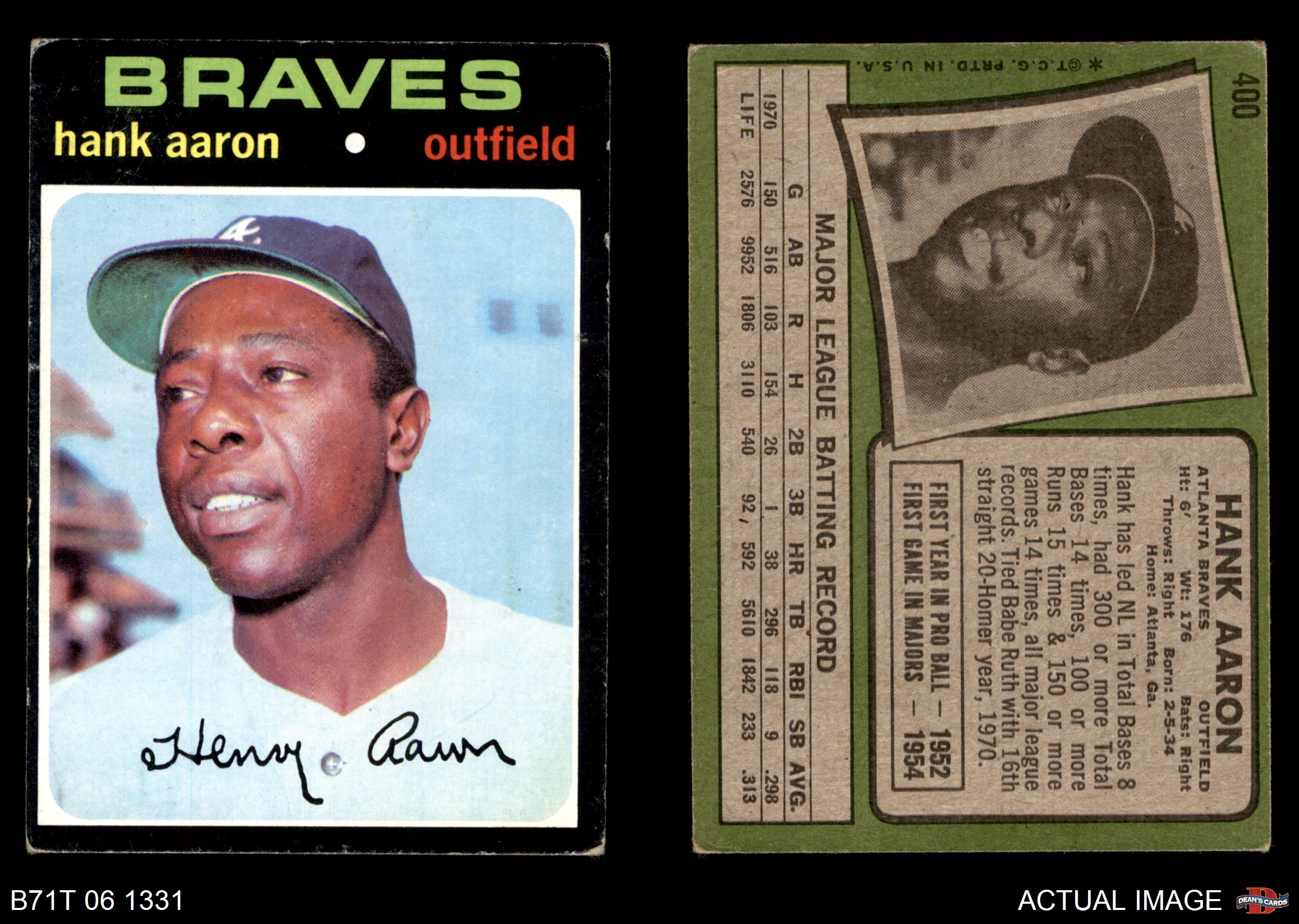

One of the sport's great stars despite playing for the small-market Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves throughout a major league career that spanned from 1954 to 1976, Aaron still holds major league records for RBIs (2,297), total bases (6,856) and extra-base hits (1,477), and he ranks among MLB's best in hits (3,771, third all time), games played (3,298, third) and runs scored (2,174, fourth).

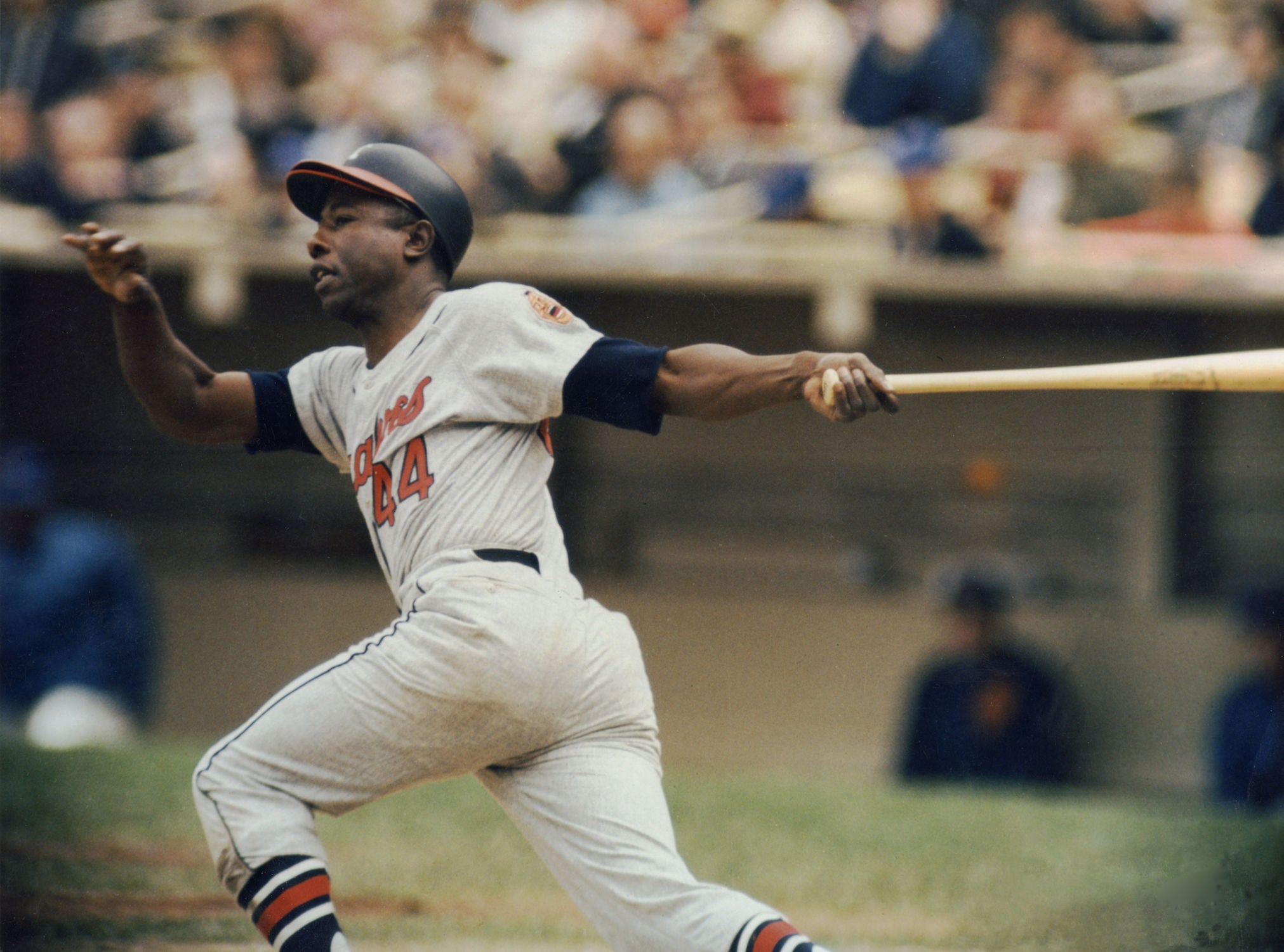

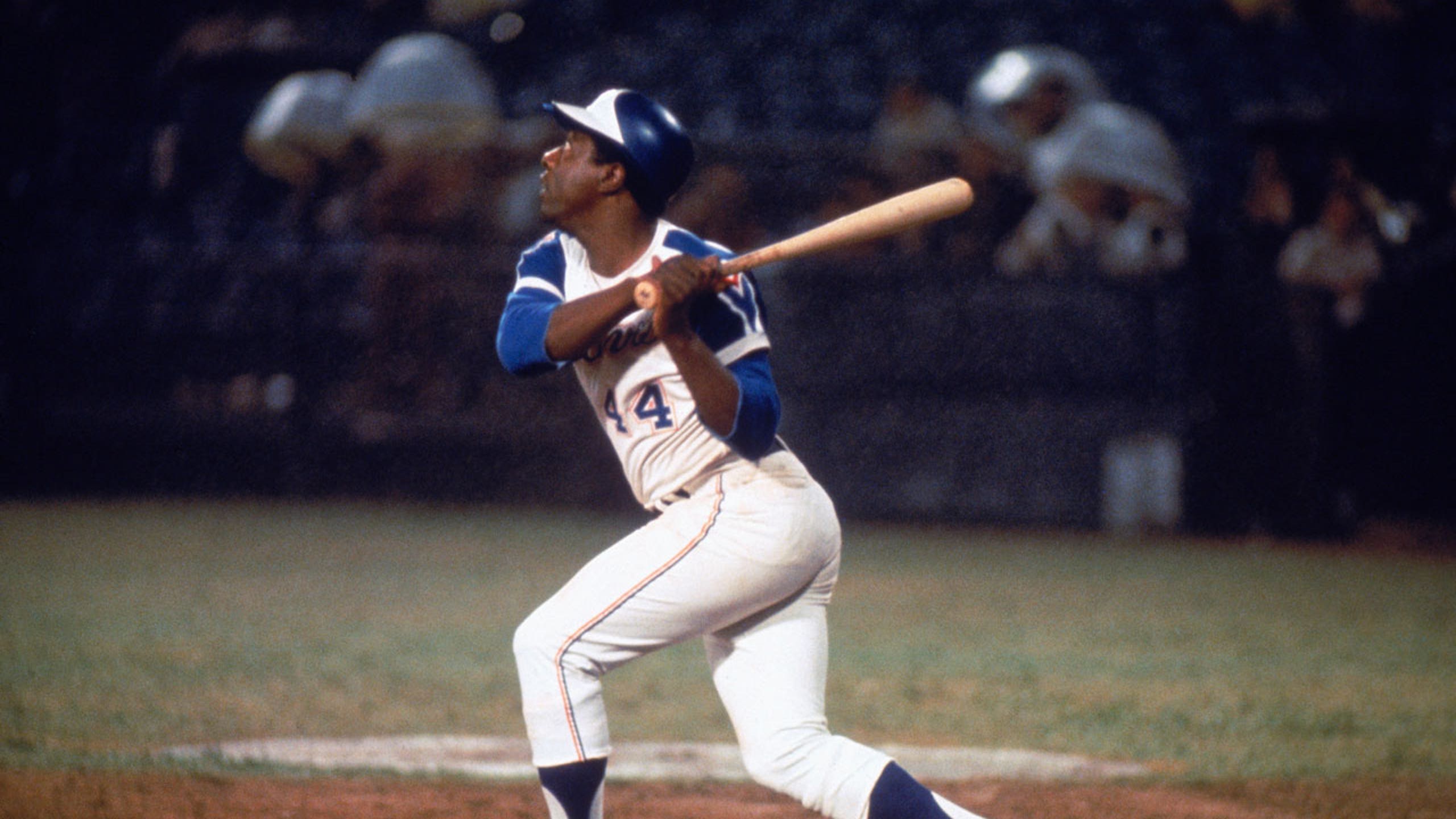

But it was Hammerin' Hank's sweet home run swing for which he was best known.

A 6-foot, 180-pounder, Aaron broke Babe Ruth's hallowed home run mark on April 8, 1974, slugging his record 715th off Los Angeles Dodgers left-hander Al Downing in the fourth inning as 50,000-plus fans celebrated in Atlanta. In one of baseball's iconic moments, Aaron trotted around the basepaths -- despite briefly being interrupted by two fans -- and ultimately touched home plate, where teammates hoisted him, his parents embraced him and he was interviewed by a young Craig Sager.

Aaron went on to play two more seasons and finished with 755 career home runs, a mark that stood as the major league record until Barry Bonds broke it in 2007.

"We are absolutely devastated by the passing of our beloved Hank," Braves chairman Terry McGuirk said in a statement. "He was a beacon for our organization first as a player, then with player development, and always with our community efforts. His incredible talent and resolve helped him achieve the highest accomplishments, yet he never lost his humble nature. Henry Louis Aaron wasn't just our icon, but one across Major League Baseball and around the world. His success on the diamond was matched only by his business accomplishments off the field and capped by his extraordinary philanthropic efforts.

"We are heartbroken and thinking of his wife Billye and their children Gaile, Hank, Jr., Lary, Dorinda and Ceci and his grandchildren."

Kemp issued an order to have the flags fly at half-staff at all state buildings in Georgia until sunset on the day of Aaron's funeral to honor his "groundbreaking career and tremendous impact on our state and nation."

#FirstTake #MLB

Tim Kurkjian remembers the life of baseball legend Hank Aaron | First Take

•Jan 22, 2021

Tim Kurkjian joins First Take and remembers the life and legacy of Baseball Hall of Famer and Atlanta Braves legend, Henry Louis “Hank” Aaron.

#FirstTake #MLB

Despite allegations that Bonds used performance-enhancing drugs, Aaron never begrudged someone eclipsing his mark. His common refrain: More than three decades as the king was long enough. It was time for someone else to hold the record.

Bonds expressed his "deepest respect and admiration" for Aaron in a statement on Twitter.

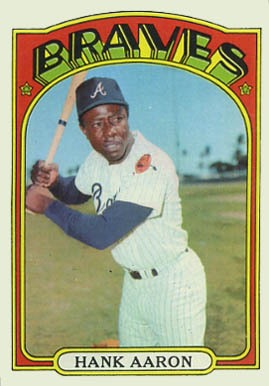

Aaron finished his career with a host of accolades. He was the National League MVP in 1957 -- the same year the Braves won the World Series -- a two-time NL batting champion (1956, '59), a three-time Gold Glove winner in right field (1958-60) and a record 25-time All-Star, earning that honor every season but his first and last.

He finished his career back in Milwaukee, traded to the Brewers after the 1974 season when he refused to take a front-office job that would have required a big pay cut.

The Brewers will wear No. 44 on their jersey sleeves throughout the 2021 season as a tribute to Aaron.

Aaron was enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, receiving 97.8% approval in his first year on the ballot, nine votes short of being the first unanimous choice ever. In 1999, MLB created the Hank Aaron Award, given annually to the best hitter in both the AL and NL.

"Hank Aaron is near the top of everyone's list of all-time great players," said MLB commissioner Rob Manfred in a statement -- one of many to appear on social media Friday. "His monumental achievements as a player were surpassed only by his dignity and integrity as a person. Hank symbolized the very best of our game, and his all-around excellence provided Americans and fans across the world with an example to which to aspire. His career demonstrates that a person who goes to work with humility every day can hammer his way into history -- and find a way to shine like no other."

Off the field, Aaron was an activist for civil rights, having been a victim of racial inequalities. Aaron was born Feb. 5, 1934, in Mobile, Alabama, and didn't play organized high school baseball because only white students had teams. During the buildup to his passing of Ruth's home run mark, threats were made on his life by people who did not want to see a Black man break the record.

"If I was white, all America would be proud of me," Aaron said almost a year before he passed Ruth. "But I am Black."

Aaron was shadowed constantly by bodyguards and forced to distance himself from teammates. He kept all those hateful letters, a bitter reminder of the abuse he endured and never forgot.

"This is a considerable loss for the entire city of Atlanta," Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said in a statement. "While the world knew him as 'Hammering Hank Aaron' because of his incredible, record-setting baseball career, he was a cornerstone of our village, graciously and freely joining Mrs. Aaron in giving their presence and resources toward making our city a better place. As an adopted son of Atlanta, Mr. Aaron was part of the fabric that helped place Atlanta on the world stage. Our gratitude, thoughts and prayers are with the Aaron family."

The NFL's Atlanta Falcons, MLS' Atlanta United and Georgia Tech's football team all said they would retire their No. 44 jerseys in Aaron's honor for the 2021 season.

Aaron, who initially hit with a cross-handed style, was spotted by the Braves while trying out for the Indianapolis Clowns, a Negro Leagues team. The Giants also were interested, but Aaron signed with Milwaukee, spent two seasons in the minors and came up to the Braves in 1954 after Bobby Thomson was injured in spring training.

Aaron's debut was hardly glowing: He struck out twice and hit into a double play while going 0-for-5. His first home run came before April was done, against Vic Raschi. By season's end, the rookie had put up promising numbers: 13 homers, 69 RBIs and a .280 average.

He was a full-fledged star by 1957, when he led the Braves to that World Series victory over Mickey Mantle's New York Yankees. The following year, Milwaukee made it back to the Series, only to blow a 3-1 lead and lose to the Yankees in seven games. Though he played for nearly two more decades, Aaron never came so close to a championship again.

After retiring as a player, Aaron made amends with the Braves for trading him away. He returned as a vice president and director of player development, a task he held for 13 years before settling into a largely ceremonial role as senior vice president and assistant to the president in 1989. He hoped more Black players could find front-office work after their playing days were finished.

"On the field, Blacks have been able to be super giants," he once said. "But once our playing days are over, this is the end of it and we go back to the back of the bus again."

Aaron showed he wasn't hesitant about speaking out on the issues of the day, often speaking bluntly but never bitterly on the many hardships thrown his way -- from the poverty and segregation of his Alabama youth to the ugly, racist threats he faced during his pursuit of one of America's most hallowed records.

"With courage and dignity, he eclipsed the most hallowed record in sports while absorbing vengeance that would have broken most people,'' President Joe Biden said. "But he was unbreakable.''

Former President Jimmy Carter, described Aaron as "a personal hero.''

"A breaker of records and racial barriers, his remarkable legacy will continue to inspire countless athletes and admirers for generations to come," said Carter, a Georgia native who often attended Braves games with his wife, Rosalynn.

George W. Bush, a one-time owner of the Texas Rangers, presented Aaron in 2002 with the Presidential Medal of Freedom -- the nation's highest civilian honor.

"The former Home Run King wasn't handed his throne," Bush said in a statement Friday. "He grew up poor and faced racism as he worked to become one of the greatest baseball players of all time. Hank never let the hatred he faced consume him."

Former MLB commissioner Bud Selig called Aaron, who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002, a "true Hall of Famer in every way."

"Besides being one of the greatest baseball players of all time, Hank was a wonderful and dear person and a wonderful and dear friend," Selig said in a statement. "Not long ago, he and I were walking the streets of Washington, D.C. together and talking about how we've been the best of friends for more than 60 years. Then Hank said: 'Who would have ever thought all those years ago that a black kid from Mobile, Alabama would break Babe Ruth's home run record and a Jewish kid from Milwaukee would become the Commissioner of Baseball?'"

Aaron's death follows that of seven other baseball Hall of Famers in 2020 and two more -- Tommy Lasorda and Don Sutton -- already this year.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/30761133/let-us-appreciate-grace-uncommon-decency-henry-aaron

Let us appreciate the grace and uncommon decency of Henry Aaron

SportsCentury Hank Aaron

•Nov 21, 2020

ESPN Classic's biographical series "SportsCentury" episode on MLB Hall of Fame outfielder Hank Aaron.

When I first reached out to Henry Aaron to tell him I was interested in writing a book about his life, he did not want to talk to me. He was convinced the public had no interest in him, except to have him serve as their proxy to criticize Barry Bonds as Bonds neared his all-time home run record. Henry's titanic statistical achievements cemented, he was tired of the constant misinterpretation of his worldview. The journalistic response to his critique of race relations had turned him inward. In print, he saw himself portrayed as bitter, always bitter, when in fact he was merely telling the story of his life -- answering the questions he was asked. When we first spoke, he was resigned to the idea that people did not want to really know him. Instead, they wanted him to reflect a sense of their own better selves. His perspective of his greatest moment -- breaking Babe Ruth's all-time home run record -- was somehow less important than theirs, and his view that the greatest moment of his career finally ended the worst period of his athletic life complicated their enjoyment that the night of April 8, 1974, brought them. The public reduced the effects of his own journey to him simply being bitter without cause.

I asked him whether he wanted to be known. "Yes, I do," he told me. "But whenever I say something, the writers get it wrong. Then they try to correct it, and then I have to correct the correction, and finally I just decided it wasn't worth it. Don't say anything. Keep to myself. If you don't say anything, they can't get it wrong."

Henry's critique was central to his life, and the critique was a simultaneously gentle yet ferocious indictment. Over the course of his 86 years, America asked him to do everything right. It asked him to pull himself up by his bootstraps: Henry's father had built the family house with saved money and leftover planks of wood and nails he scavenged from vacant lots around the Toulminville section of Mobile, while he had taught himself to play baseball. America asked him to put in the hours and the hard work and to not complain: Henry played 23 seasons and never once went on the then-disabled list after his rookie season ended three weeks early because of a broken ankle. No special favors. No handouts. America asked him to believe in meritocracy, the meritocracy of the record books and the scoreboard.

America asked him to do all of the things, and when he did them, he found himself at the top of his nation's greatest sporting profession through the merit of statistics. In return, the FBI told him his daughter was the target of a kidnapping plot. For nearly three years he required a police escort and an FBI detail for himself and his family. He finished the 1973 season with 713 home runs -- one shy of tying Ruth's record -- and believed he would be assassinated in the offseason. He had received enough letters to convince him so. He received death threats from 1972 to 1974 -- all for doing what America asked of him.

|

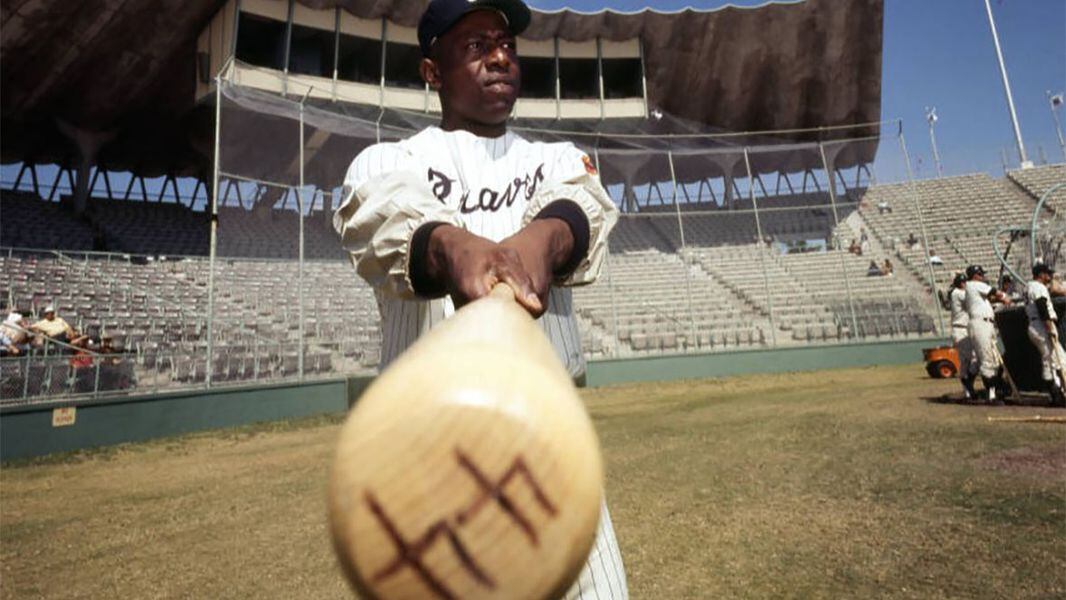

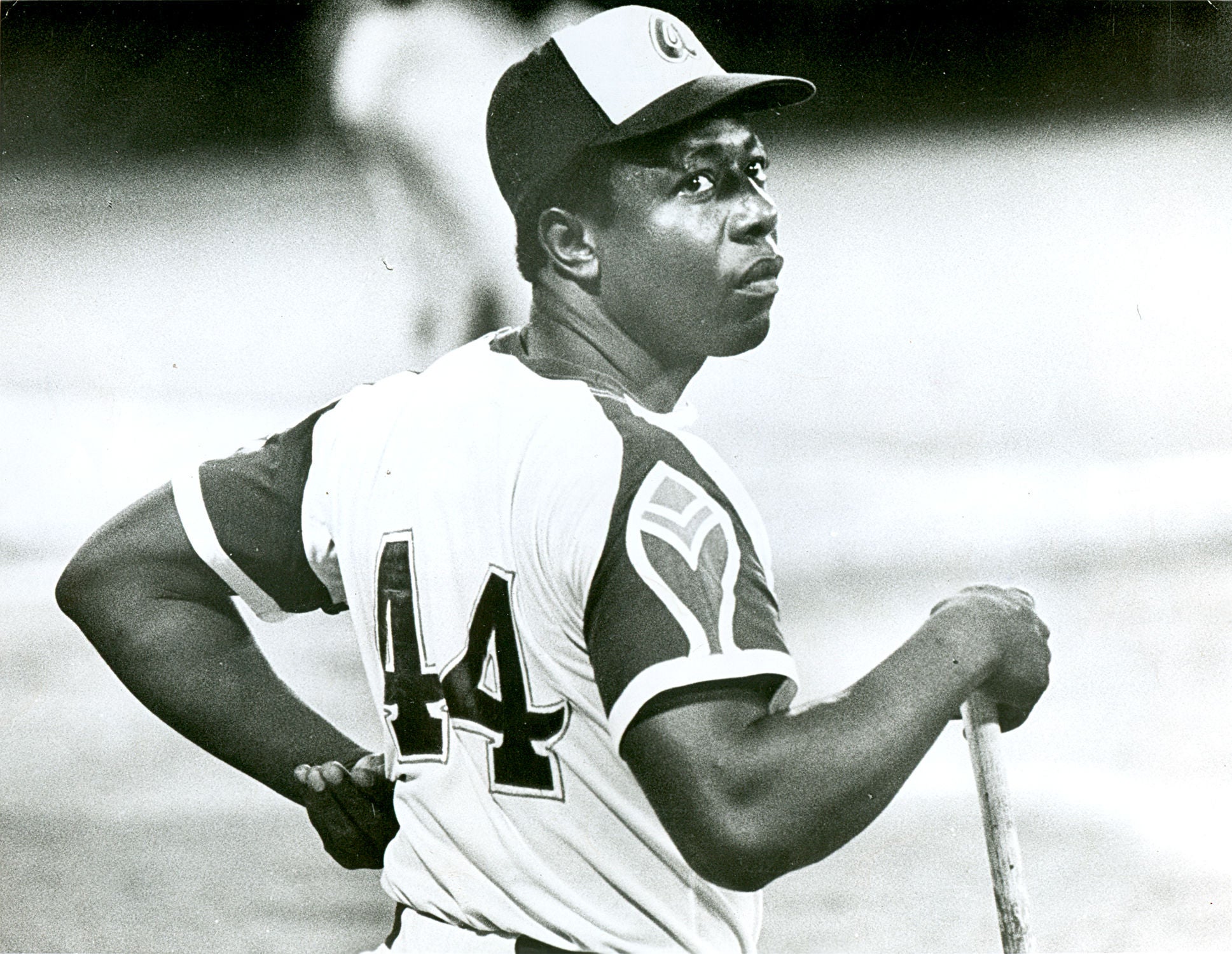

| Outfielder Hank Aaron, then with the Milwaukee Braves before a game in the 1960s. Focus on Sport/Getty Images |

He was unconvinced a writer would take him seriously, because over his lifetime precious few had. As he seemed to warm to the idea -- or at least not view it hostilely -- he asked me a question I would never forget: "How many pages will it be?" It seemed so odd -- yet the question was self-explanatory and my response would telegraph to him how seriously I took the project. Biographies of towering figures in the classically grand tradition are thick. They are doorstops. They are meaty paperweights that sit on the bookshelves whose girth scream importance -- even if 95% of the population never finishes them, even if I was thinking, "Mr. Aaron, the only thing worse than writing a lousy book is writing a really long, lousy book." To him, big people got big books, and because he did not yet have one, he did not think people cared. Henry wanted to make sure I was willing to put in the work to understand a life.

He possessed an uncommon decency, a quality in short supply today. His decency convinced him no one was interested in him, not because he did not believe his life was important, but because he was not an anti-hero whose deep flaws, scandal and misdeeds made him more marketable. He was just a solid person. No jail. No arrests. No substance abuse, falls from grace, or mistresses.

Henry understood at once his place in the world and how his talent had created a different lane for him. The people who once dismissed him, and his people, made exceptions for him because he was The Hank Aaron. He was rightfully distrusting of them. He watched the change in how America viewed him as his talent kept proving its cultural racism wrong. And instead of his constant defeat of its presuppositions, the culture did not change, but in its eyes, he did. Henry became dignified.

In the African American story, dignity is such a sly and deceptive word, simultaneously complimentary and condescending, and dignity was attached to Henry like a surname. Its affixation to him, of course, said more about his world than it ever did about him. For what was called dignity was simply an acceptable response to hostility, and it was easier for writers and broadcasters, fans and executives to concentrate on his response to hostility than the hostility itself. It is a common expectation of African Americans that they be more conciliatory and not vengeful, invested and not apathetic, constantly brave and aspiring and dignified in the hostile territory of indignity. When he smiled at the hostility, he was dignified. When he did not, he was bitter. Dignity has always felt like code for treating white incivility as inevitable behavior, of not ever punching the punchers.

His life seemed to mimic his career, a long, triumphant marathon where in the end his values proved sturdier than the temporary sensations of the moment. And through all the years -- like hitting 20 home runs for 20 straight years -- he was still there.

There was a hidden fear I felt for my own family that I also felt for him: the worry that Black people in their 80s and 90s would die before the 2020 election, and during the last part of their lives they would bear witness to both the elation of an African American president and a hostile response so severe it was reminiscent of the previous backlashes to Black success. I was with Henry at his house in Atlanta on Oct. 1, 2008. After we had finished talking, he and his wife, Billye, were heading to the polls to vote early for Barack Obama, the act of doing so its own statement. Her first husband was the late civil rights activist and Morehouse College professor Dr. Samuel Woodrow Williams, and before his death in 1970, Billye had long been part of the Atlanta civil rights movement. The Braves moved to Atlanta after the 1965 season, and Henry met with Andrew Young, Ralph Abernathy and Martin Luther King, Jr., and told them he did not believe he was sufficiently doing his part in the movement. King and Young assured him that as a Black pro sports star in the South, his role was significant. To cast a presidential ballot for a Black man 42 years later was for them a major emotional event.

When Henry and I last saw each other, in Atlanta in early 2018, this -- along with tennis ("Do you think Serena will get another one?" he asked) and the NFL playoffs -- is what we talked about. And he reminded me of his father working at the Mobile shipyard during World War II, when white workers rioted because African Americans were being hired, taking what they believed was theirs and theirs only. Henry was dignified, but he never forgot what was done to his people and by whom.

He never mentioned not surviving the vicious presidency of the past four years, but I worried about it for him, as I did for all the Black people of his generation for whom the vote was something some had literally died for -- a vote that today was being strategically suppressed and delegitimized. When I wished him a Happy New Year a few weeks ago, he was grateful for surviving, and excited for Georgia. What he saw in the country reminded him of where it had been, of how deeply the past had wounded him, and he feared seeing the past in the future. We talked about losing Joe Morgan and Jimmy Wynn, Tom Seaver and Whitey Ford and Bob Gibson and Lou Brock and Al Kaline with pain and absolutely no hints that day that he and I would never speak again.

Before we hung up the phone, he said what he always said, "Call, any time. I love when we talk," and I said I would, but I also knew the truth: I never called him nearly enough because he was the great man, Henry Aaron, and one does not respect an invitation by overstaying one's welcome. Now, that time cannot be recovered.

When he was behind Ruth, he was ahead of America. When he passed Ruth, America still had not caught up to him -- and now, respected as royalty, I asked him if there was ever a quiet moment when he could sit back with an umbrella in his drink and revel in triumph, that he indeed had made it. He said yes so many times, delighted in the happiness he had not felt in 1974, making bitterness the inappropriate adjective it always had been. He challenged baseball and had reconciled with it. He was an unquestioned immortal, no longer slighted. Jeff Idelson, former president of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, saw to that, as did his friend and former baseball commissioner, Bud Selig, who made it clear to all underlings at MLB that Henry was a made man, not to be harassed. President George W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 2009, Henry, his wife, Billye, and I were sitting in a conference room at the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. I was trying to comprehend the historical arc of Henry Aaron, and told him he represented so much of the Black American aspirational journey. I said to him, "You went from your mother hiding you under the bed when the Klan marched down your street as a toddler to sleeping in the White House as the invited guests of the president."

"No, no, no, Mr. Bryant," Billye Aaron interrupted me with a proud smile. "We didn't sleep at the White House. We slept at the White House twice."

A

real world legend: Henry 'Hank' Aaron's resolve made him an icon of the civil

rights movement

·Yahoo Sports Columnist

January 22, 2021·5 min

read

Bear down. Bow down to no one. Pay it forward.

These are the lessons that Jackie Robinson taught Henry Louis Aaron as Aaron embarked on his remarkable career in Major League Baseball, and Aaron took the words to heart.

Aaron, “Hammerin’ Hank” to generations of baseball fans, died on Friday at age 86.

The term “GOAT” and the word “legend” get thrown around too freely these days, but over the last century there are few athletes, few people of any background, for whom both are incredibly apt. Aaron is arguably the greatest baseball player of all time, and for what he did on the field while absorbing arrow after arrow, so many of them tipped with the poison of racism, he is a legendary figure.

As happened with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Muhammad Ali before him, Aaron’s death brought a flood of tributes and remembrances.

But Aaron, like King and Ali, only became beloved to a wider majority of Americans once he got older. Once his powerful swing and incredible consistency were diminished, once he was no longer in the headlines year after year for succeeding in a game so many believed he had no right to excel at, certainly not once he began threatening the numbers of Babe Ruth.

To say he persevered cheapens his greatness, because who among us could report for work every day to a ballpark with little (if any) security, thousands of fans who loathe you for the color of your skin, and the fear that one of them is there to make good on the promise to kill you they made in a written letter?

Aaron did that.

He never backed down.

Incredibly, he saved some of the very worst letters he received, the ones that called him the N-word over and over (one person had no issue typing out the slur, the most offensive and demeaning word in this country, in capital letters but would not type out “damn,” which is a window into the depths of that individual's sickness), and spoke of how the incessant hate mail — the Braves received up to 3,000 letters a day as he neared Ruth’s home run record — changed him and robbed him of being able to fully celebrate his achievement.

Aaron revered Robinson, and as Robinson had influenced him, taught him to never take no for an answer, so did Aaron teach other Black MLB players who followed him into the league. Current Houston Astros manager Dusty Baker began his playing career with the Atlanta Braves, and Aaron was so much more than a teammate; in a statement Friday, Baker called him a “the best person that I ever knew” and the second most influential person in his life after his father.

“He taught me how to be a man and how to be a proud African-American. He taught me how important it was to give back to the community, and he inspired me to become an entrepreneur,” Baker said.

Aaron helped integrate the Class A South Atlantic League while playing for Jacksonville, Florida, and he helped integrate Atlanta after the Braves moved there from Milwaukee. A native of Mobile, Alabama, Aaron initially wasn’t a fan of moving back to the Deep South; in Milwaukee, he didn’t experience the oppression of Jim Crow rules and segregation.

Once he arrived, however, he saw the burgeoning civil rights movement and realized it was his duty to become involved and help those that looked like him. He met Dr. King but befriended Andrew Young, who would become a U.S. congressman, mayor of Atlanta and ambassador to the United Nations.

Aaron and his wife, Billye, donated money and time, in ways known, as with his “Chasing the Dream” foundation, and in secret.

As a longtime Braves executive, Aaron never stopped pushing baseball to do better about its lack of diversity in all areas, never stopped speaking up for those that looked like him.

In 2017, he said Colin Kaepernick was getting “a raw deal” from the NFL, saying, “I don’t think anybody can do the things he can do” as a quarterback, and that he would love to see other players show support for Kaepernick.

Earlier this month he and Young were at the Morehouse Medical Center to receive their first dose of the Covid-19 vaccine — a way to show fellow Black citizens who are rightfully skeptical of medical research after the horror of the Tuskegee experiment and continuing, documented mistreatment of African-Americans by medical professionals, that it was safe to get the vaccine. The Black community is disproportionately suffering during the pandemic, from deaths to small business closures to unemployment that is only widening the staggering wealth gap.

As recently as last summer, immediately after the killing of George Floyd, Aaron lamented to MLB.com’s Mike Lupica, “Something is so wrong in our country.”

But he was heartened by the peaceful protests, the young people of all backgrounds marching for justice. He knew they could be the ones to bring change.

And he had a message for them: “I’m not able to move around much anymore. But if I could, I’d be out there marching. I’d be right there at the front of the line.”

https://sports.yahoo.com/remembering-day-fishing-hank-aaron-110711265.html?src=rss

Remembering my day fishing with Hank Aaron revealed his Hall of

Fame principles

Joe Lapointe, Special to

Detroit Free Press

·5 min read

A few days before Hank Aaron died on Friday at age 86, I came across an old Free Press story headlined “Henry Aaron: `I Believe Somehow Things Have to Change.’” I wrote it 40 summers ago (July 27, 1980) as part of a series called “Blacks and Baseball.”

At that time, Aaron held baseball’s career record with 755 home runs and he worked as a top executive for the Atlanta Braves. At his gracious Atlanta home, he walked me back to a lake behind his house to fish and to talk.

[ How Hank Aaron pumped up ex-Tiger Denny McLain in Atlanta ]

With his hook, he stabbed several worms soon to be stolen by fish. With his keen, hitter’s eyes, he spied snakes and other critters beneath the calm surface of the lake.

His voice was calm, too, but still waters run deep. Aaron said baseball was losing Black participants in part because there were few management opportunities for former players. He predicted a rupture between Black athletic talent and the national pastime.

“Black kids just aren’t going out for baseball like they used to,” Aaron said. “After the Black baseball player’s career is over, he’s gone, he’s no longer part of the system. That’s the end of it. Kids that could probably play baseball are ... going into basketball ... I can see baseball being a dying sport among Black people.”

When Aaron told me these things in 1980, 17.4% of major league players were Black. The following year, 1981, the Black percentage was 18.7, its highest ever. Since then, the Black percentage has plunged to as low as 6.7% in 2016. Last season, it was 7.8%.

[ 'Quiet confidence': Ex- teammate recalls Hank Aaron as a player and person ]

“I didn’t know much about Babe Ruth when I was growing up in Alabama,” Aaron said. “Back then, professional baseball was not even talked about. Only thing you’d talk about in baseball, you’d talk about the Negro Leagues.”

In 1952, Aaron started his baseball career in those leagues with the Indianapolis Clowns. In 1954, he joined the Milwaukee Braves, which had recently moved from Boston. In 1974, Aaron surpassed Ruth’s record of 714 home runs. (Both now trail Barry Bonds’ mark of 762).

But in 1980, our conversation was not about home runs but about management opportunities for Black people in baseball. Aaron was adamant.

To make his point, Aaron had recently snubbed MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who wanted to give him an award. Six years before that, in 1974, Kuhn missed Aaron’s record-setting 715th. home run due to a prior commitment.

But Aaron emphasized to me that his protest was more than personal. He said Black players were rarely considered for jobs as managers or executives. This drew a backlash.

[ Yes, Barry Bonds is baseball's home run king – but Hank Aaron's legacy runs deeper ]

He recalled an argument with Monte Irvin, another Black Hall-of-Fame player who worked for the commissioner. Irvin scolded Aaron for snubbing Kuhn. One word led to another.

“And we got in an argument, I mean a serious argument, right there in Club 21,” Aaron said.

“He said I made him look like an ass and I said `You serious?’ ... He was saying he thought for some reason that baseball has been fair with Blacks. And I can’t see that. I can’t buy it. I tell Monte, I don’t care if anybody believes me or not, as long as a breath is in my body, someone has to show me they’re going after a Black manager, they can have Black people working in the front office, they can have a Black trainer, I’ll say then that baseball has been fair to Blacks.”

When Aaron died Friday, baseball’s 30 teams had two Black managers: Dave Roberts of the World Series champion Los Angeles Dodgers and Dusty Baker of the Houston Astros.

There are no Black general managers; Ken Williams is an executive vice-president of the Chicago White Sox.

At the time, Aaron told me he might boycott his Hall of Fame induction in 1982.

“I’m having second thoughts about going to Cooperstown,” he said. “If things don’t get any better, then I’m going to have to think about it.”

In the end, he went.

It is fascinating to re-read my piece from 1980 and realize how much has changed and how much has stayed the same. In the course of our conversation, Aaron said “Black kids know they can’t be president.”

Twenty-eight years later, Barack Obama won the presidential election, becoming the Jackie Robinson of politics.

Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947, only 33 years before Aaron and I spoke that day on the fishing dock.

Aaron expressed dismay at criticism he’d read from white sports journalists who called him ungrateful.

Challenging me in an earnest tone, he said newspapers needed Black sports journalists. At the time, the Free Press had none; Aaron said it was the same in Atlanta.

“The basketball team is almost entirely Black,” Aaron said, “and you mean they can’t find a Black sports writer?”

Aaron said a Black reporter might relate better to Black athletes.

“Some (white) people may say 'I realize where you’re coming from,’” Aaron said, “but nobody realizes how Henry Aaron grew up in Mobile, Alabama, with eight kids, mother and father didn’t know where they were going to get a piece of bread the next day. These people who write about Henry Aaron, they don’t know me. They’ve never lived across a railroad track.”

At one point, Aaron stopped himself and his tone turned almost apologetic.

“I don’t mean to hop on every little thing,” he said, reeling in his empty line.

As the sun set in the summer dusk, he seemed unburdened. As he headed back to his house without a fish, I went to my rental car with a full notebook and the realization that fishing isn’t always about catching fish.

Joe Lapointe is a former Detroit Free Press and New York Times sports reporter. Now retired, contact him at joenytimes@yahoo.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Remembering my day with Hank Aaron revealed Hall of Fame principles

Hank Aaron remembered at funeral by Bill Clinton, Bud Selig, others

ATLANTA -- The Hammer made one last trip to the spot where he hit No. 715.

After a nearly three-hour funeral service Wednesday that featured two former presidents, a long-time baseball commissioner and a civil rights icon, the hearse carrying Hank Aaron's body detoured off the road bearing his name to swing through the former site of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

That's where Aaron broke an iconic record on April 8, 1974, eclipsing the home run mark established by Babe Ruth.

The stadium was imploded in 1997 after the Braves moved across the street to Turner Field, replaced by a parking lot for the new ballpark. But the outer retaining wall of the old stadium remains, along with a modest display in the midst of the nondescript lot that marks the exact location where the record-breaking homer cleared the left-field fence.

A steady stream of baseball fans have been stopping by the site -- comprising a small section of fence, a wall and a baseball-shaped sign that says "Hank Aaron Home Run 715" -- since "Hammerin' Hank" died Friday at age 86. The fence is covered with flowers, notes and baseball memorabilia.

Fittingly, Aaron's funeral procession went by the display on the way to his burial at South-View Cemetery, the oldest Black burial ground in Atlanta and resting place for prominent civil rights leaders such as John Lewis and Julian Bond.

The police-escorted line of cars passed near the gold-domed Georgia state capitol, went under the tower that displayed the Olympic torch during the 1996 Atlanta Summer Games, and headed down Hank Aaron Drive.

At the bottom of a hill, the procession took a sharp right turn toward the site of the former stadium. Aaron's flower-covered hearse and all the vehicles that followed did a loop through the circular parking lot, which covers the footprint of the cookie-cutter stadium that became home of the Braves after they moved from Milwaukee in 1966.

It was a touching tribute that capped off several days of remembrances for one of baseball's great players. The Braves held a memorial ceremony Tuesday at their current home, suburban Truist Park.

The funeral service touched as much on Aaron's life beyond the field as it did his unparalleled baseball accomplishments, honoring his business acumen, charitable donations, and steadfast determination to provide educational opportunities for the underprivileged.

"His whole life was a home run,'" former President Bill Clinton said. "Now he has rounded the bases."

Clinton said the two became close friends after Aaron endorsed him during the 1992 presidential campaign, when he pulled out a narrow victory in Georgia. Clinton had been the last Democrat to win the state until Joe Biden edged Donald Trump in November.

"For the rest of his life, he never let me forget who was responsible for winning," Clinton quipped, drawing a few chuckles during the mostly somber ceremony. "Hank Aaron never bragged about anything -- except carrying Georgia for me in 1992."

Bud Selig, who was commissioner of Major League Baseball for more than two decades and another close friend of Aaron's, said one of his fondest memories was being at Milwaukee's County Stadium as a fan for the pennant-clinching homer that sent the Braves to the 1957 World Series.

"The only ticket I could get was an obstructed-view seat in the bleachers behind a big, metal post," the 86-year-old Selig said. "The image of the great Aaron, deliriously happy, being hoisted on the shoulders of his teammates and carried off the field is indelibly imprinted in my memory."

Andrew Young, a top lieutenant of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil right movement and a former Atlanta mayor, said Aaron helped transform his adopted hometown into one of America's most influential cities.

The Braves moved to the Deep South during an era of intense racial strife, Young pointed out, but having one of the game's greatest Black players helped ease some of the tensions.

Atlanta continued its explosive growth, eventually landing such major sporting events as the Olympics, multiple Super Bowls and World Series, as well as numerous college sports championships.

"Just his presence, before he hit a hit, changed this city," Young said. "We've never been the same."

Only about 50 people attended the funeral service because of COVID-19 restrictions. Other sent videotaped messages, including another former president, Jimmy Carter.

Remembering his tenure as governor of Georgia, the 96-year-old Carter joked that after the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce gave Aaron a new Cadillac, he followed up with "a $10 tag" to go on the vehicle. It said "HLA 715," a nod to the initials for Henry Louis Aaron.

The two became close friends and even took vacation trips to Colorado with their wives. In one pursuit, at least, Carter was the better athlete.

"Hank and I both learned how to ski together," Carter said. "He skied fairly well. I was a little bit better than that on skis."

A longtime Braves fan, Carter noted that he was at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium the night Aaron hit his iconic home run.

On Wednesday, the Hammer went there for the final time.

Hank Aaron diversity fund starts with $2M in pledges from Atlanta Braves, MLB, players' association

The Atlanta Braves plan to honor Hank Aaron during the upcoming season, with the first of those initiatives being a $1 million donation to establish the Henry Louis Aaron Fund, which will work to increase minority participation among players, managers, coaches and front-office personnel.

That was an issue Aaron took a keen interest in throughout his life. He often criticized the lack of Black managers and general managers in Major League Baseball. He fretted that fewer Black people were playing the game.

"We want to continue Hank's amazing work in growing diversity within baseball now and in the years to come," Braves chairman Terry McGuirk said in a statement. "I believe this seed money is just the beginning for this growing fund and I'm certain other companies and organizations who have worked with Hank over the years will join us and add to this call to action to develop talent and increase the diversity on the field and in the front offices across the league."

The Braves' donation will be matched by $500,000 apiece from MLB and the players' association.

"Henry Aaron was a Hall of Fame player, a front office executive, a mentor, a colleague and a friend. In each of these roles, he was a tireless advocate for better representation of people of color throughout our sport," MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. "As a philanthropist and businessman, this celebrated power hitter was most passionate about empowering others. We are proud to honor his legacy through this joint donation to the Henry Louis Aaron Fund, and commit ourselves to continue building toward greater diversity and representation in the game Hank loved dearly."

Aaron, whose 755 career home runs long stood as baseball's all-time best, died last week from natural causes at the age of 86, and a memorial service in his honor was held Tuesday at Truist Park in Atlanta.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

|

| https://6abc.com/hank-aaron-death-did-die-hammerin-baseball-hall-of-fame/9905703/ |

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2101.30 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2038 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/68715884/lex_hank_aaron_getty_ringer.0.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/68707904/51455615.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment