Even though Impossible Burgers had been on the market and were being eaten by vegetarians for a couple of years, when Burger King started selling its Impossible Whopper last year along with places like Red Robin and others, reactionaries and nay-sayers started to freak out about its safety.

Even the president of Whole Foods dissuaded people from eating it too often because it's processed food and not "whole" food, which plays in the marketing campaign of a company called WHOLE foods but is also not terrible advice. Diet should be about variety, like in paleolithic times when we hunted gathered just whatever was around, which was not limited to one thing unless you lived on an island with one coconut tree like in that old Looney Tunes cartoon.

Like everything in the world these days, wading through all the rhetoric is an exercise in a person's critical thinking skills and ultimately boils down to whom one trusts and why.

Like cnet, a go to news source for me since it was exclusively a computer-tech industry site, is such a source:

This unprecedented burger concoction is built on four ingredient foundations: protein, fat, binders and flavor.

The juicy sizzle when an Impossible Burger hits the pan or grill comes from coconut oil and sunflower oil, the burger's fat sources. To hold everything together, Impossible Foods uses methylcellulose, a bulk-forming binder that also serves as a great source of fiber.

As for flavor, well, this is where things get interesting. Impossible Foods employs heme as the main flavor compound in its burger. Heme is an iron-containing compound found in all living organisms. Plants, animals, bacteria, fungi... if it's alive, it contains heme.

In animals, heme is an important part of the protein hemoglobin, which carries oxygen throughout your body via blood. Know how your mouth tastes metallic when you accidentally bite your lip? That's heme.

In plants, heme still carries oxygen, just not via blood. The Impossible Burger contains heme from the roots of soy plants, in the form of a molecule called leghemoglobin. Food scientists insert DNA from soy roots into a genetically modified yeast, where it ferments and produces large quantities of soy heme.

.....................Okay, GMO is actually a bit of a misnomer as there is no O; there is no ORGANISM as will be explained later. It's more like GMP, Genetically-Modified Protein.

So, there's that. A Google search of "hormones in impossible burger" or "impossible burger safe" yields some interesting results.

Okay, this non-profit has a good reputation -- hey, Michael Pollan endorsed it -- unfortunately, their dismissal of Impossible Burger is riddled with inaccuracies and errors.

And so, this is just not true. It has been studied. It has been regulated, and it is part of a solution to our factory and farm and climate crisis.

You can read the "science" this organization reported, which has no actual science in it, no corroboration of "facts," and many things that are just wrong as reported and corroborated by many other sources.

One of the attempted take downs on Impossible Burger is that it contains human estrogen, and ridiculous conspiracy theory is that it will give men breasts. That's so absurd it makes me Laugh Out Loud.

Here's just two of the many sources, two very historically credible sources, that reported the Impossible Burger does not contain human estrogen.

There's criticisms that IMPOSSIBLE BURGER is "processed" and contains too many ingredients and is not a "whole" food. Well, BEEF:

This VOX article reviews all the science and misinformation and makes a clear determination about where the backlash is coming from and what the truth really is. Read the whole thing, but I will share a nugget.

I have become a huge fan of Rebecca Watson and her videos. I agree with her about 98% of the time. There's a few opinions within videos and a couple of videos, I find problematic, but I am still forming my counter arguments, so I am not inclined to dismiss anything she says outright. She is smart, funny, and uses great critical thinking based firmly in SCIENCE.

To conclude all evidence you need for the safety of plant-based burger substitutes, especially IMPOSSIBLE BURGER, here her video, the transcript, followed by the article she touts highly, which is quite excellent.

Debunking Some Impossible Burger Myths

Transcript:

As I’ve mentioned in the past, I’m mostly vegetarian. I occasionally eat fish, but I avoid all other meat and I don’t eat cephalopods because they’re too damn smart. It’s like they’re alien lifeforms. I can’t do it. It’d be like eating ET.

I think if most people drastically cut down on the amount of meat they eat, whether that means going vegan, or vegetarian, or just incorporating a “meatless Mondays” kind of mindset, the world would be a better place. We’d put out less pollution, take up less land, and contribute less to the otherwise senseless torture and murder of innocent animals.

It’s actually very easy to be vegetarian these days, especially if you live in the developed world and are middle class. I’m excited to say that it’s getting even easier, with new options like Impossible Burgers hitting the market in more places than ever. The Impossible Burger is a marvel of science -- it’s made entirely of plant material, but it “bleeds” like a real hamburger. Meat eaters who I know who have tried it generally say that if you gave it to them and didn’t tell them it was a veggie burger, they’d have no idea. That’s never been super important to me, because I prefer the taste of vegetables and mushrooms and things to the taste of hamburger, but it IS important for millions of people who can’t imagine giving up meat.

Impossible Burgers have been in select restaurants for awhile now, but they just hit a huge new milestone with Burger King picking them up to make an Impossible Whopper. That kind of visibility and accessibility is honestly a dream come true for people who realize that we’re not just going to make everyone go vegan overnight, and that we have to take small steps to get people on board with reducing their meat consumption and thinking more critically about what they’re eating.

And speaking of thinking critically, just this week I stumbled upon two delightful arguments against the Impossible Burger. I will deal with them in order of seriousness.

First up,

Right Wing Watch drew my attention to Rick Wiles, an internet radio pundit who has appeared on Fox News and once worked for various Christian television networks. Wiles is sort of like Alex Jones, but he has actually criticized Jones in the past for his “controversial” statements about the Sandy Hook murders, saying that Jones’s polemics could cause a government crackdown on shows like theirs.

So Wiles is like a moderate Alex Jones. Got it? So Wiles hears about Impossible Burgers coming to Burger King and he announces this:

This is a nightmare world that they’re taking us into. They’re changing god’s creation. Why? They wanna change human dna so that you can’t be born again. (Hmm.) That’s where they’re going with this, to change the dna of humans so it will be impossible for a human to be born again. They want to create a race of soulless creatures on this planet.”

Yeah that’s pretty moderate for 2019 I gotta admit. A few things about this -- first, I had no idea that being born again is something that happens on a genetic level. Silly me, I didn’t know scientists had found the soul, or that modern Christians claimed it even could be found after, you know, two millennia of trying. Second, I had no idea that eating a veggie burger could literally change my DNA. I didn’t know that, probably because it’s not actually true. There’s nothing in an Impossible Burger that will affect your DNA, either that of your soul or otherwise.

And third, my favorite thing about this clip is that guy off-camera who audible reacts with a “hmm” just after Wiles announces his thesis, as if they’re at a cocktail party and Wiles just proposed a new interpretation he thought of during his recent rereading of Ulysses.

So that’s one negative take on the Impossible Burger. The other was brought to my attention

by someone else on Twitter, who replied to me when I reported that the Impossible Whopper was, in fact, delicious. They wrote:

“Staying clear of these until I know a bit more about the genetically modified soy they're using. Apparently, there are open questions about how safe the genetically modified soy is for human consumption.

“SO, if you grow gills or something…”

I knew immediately that this was bullshit, because honestly not to be all “the government will protect us” but Impossible Burgers have been on the market for literally three years next month. Not only would the FDA not have let them put out a product that’s unsafe, but people have been eating the absolute FUCK out of them and there have been no reports of any problems. In fact,

Impossible Foods performed their own completely voluntary recall back in March because a restaurant worker found a small piece of plastic in one. No other problems were found and the issue never affected a consumer in the least. Meanwhile, back in September a factory had to recall 100,000 pounds of ground beef because they were infected with E. coli, which led to one person dying and dozens more falling ill.

I also know it’s bullshit because the idea of “growing gills” is the sort of thing said only by people who know absolutely nothing about genetically modified food, but who hate genetically modified food anyway.

But I was curious to know if this person’s misinformation came from a particular source, and sure enough they provided me with a link to a

Huffington Post article. As an aside, I regret to inform you that the Huffington Post still exists. No idea if they ever started paying their writers.

The HuffPo article is from 2017 and is titled “FDA casts doubt on safety of Impossible Burger’s key GMO ingredient.” It’s written by contributor Ken Roseboro who says he’s the editor of The Organic & Non-GMO Report. Hmm.

Ken reports that the FDA “told lab meat manufacturer it hadn’t demonstrated safety of burger’s genetically engineered heme, which has never been in the food supply. Company put product on the market anyway.”

So what’s going on here?

Well, first of all, let’s not bury the lede:

you can relax because the FDA has, in fact, approved Impossible Burgers as being safe to eat. There was a bit of back and forth before that happened, though, and here’s why: the Impossible Burger is so much like meat because of heme, a protein that meat releases when you cook it. They found a way to get heme from a plant source, and that source is soy leghemoglobin. Leghemoglobin is the plant form of myoglobin, the thing in animals that releases heme.

Impossible Foods didn’t actually need FDA approval to use leghemoglobin because all their ingredients, including soybeans, already qualify as “generally recognized as safe,” or GRAS, which is used for foods with ingredients that the FDA has already looked at and agreed that they’re okay for people to eat. But to be on the safe side, they basically went to the FDA and said “here is the exact special ingredient we’re using. Here’s research we’ve funded to prove that it’s safe. Can you please confirm that it’s safe.” They did that because they knew people like misinformed dudes on Twitter and HuffPo would worry.

The FDA pointed out, though, that while they’ve previously recognized soybeans as safe, the leghemoglobin is contained in the root node of soy, which technically people don’t usually eat. So to be safe, they wanted some more tests done. The product could stay on the market while they cross these Ts and dot these Is.

This was unfortunate, in part because it made a bunch of hippies lose their damned minds and in part because it forced Impossible Foods to test their product on rats by feeding them loads of Impossible Burgers and making sure they don’t explode. They did it, and the product was found to be perfectly safe, but now of course you have hippies losing their minds again. How dare this company test on rats! Seriously, look at this fucking douchebag in the Independent saying

Impossible Burgers are as vegan as foie gras, and PETA

ran a fucking press release decrying them. 188 rats were killed in the testing, so that means we should just throw all the burgers in the trash, right? Even though millions of cows won’t be slaughtered in the future. Even though this paves the way for other meatless options to hit the mass market. Even though this makes vegan diets accessible to millions of people who never considered it before. The utter close-minded hypocrisy of that blows my mind. Fuck you, PETA. And fuck you, random hippies who are saying these burgers are unsafe because of FDA says so out of one side of your mouth and then saying the 188 rats who died to prove they’re safe to the FDA is a price too high out the other side of your mouth. Dear lord that was a convoluted sentence. Sorry.

I’ll close by encouraging you to go read Patrick Clinton’s incredibly informative and well-written breakdown of much of this over at the

New Food Economy, written back in 2017 but apparently missed by a lot of misinformed dipshits. And lastly I will encourage you to go to Burger King and eat an Impossible Whopper, if you were planning to hit a fast food joint anyway. You’ll be doing the Earth a favor compared to eating a regular hamburger, it’ll be (marginally) healthier for you, and you’ll be telling the food industry that you want more meatless options. Everyone wins.

https://thecounter.org/plant-blood-soy-leghemoglobin-impossible-burger/

https://thecounter.org/plant-blood-soy-leghemoglobin-impossible-burger/

The Impossible Burger is probably safe. So why is everyone worked up about “heme”?

The

flap over a key ingredient in the plant-based patty missed the real point: The

future of an important kind of food tech is being written right now

So what the hell is soy leghemoglobin, and

why is everybody so worked up about it?

I ask because of the outpouring of articles

I’ve seen in the last week or so, including some that cast aspersions on the

plant-based food startup Impossible Foods and the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA), written in response to Stephanie Strom’s recent article in The New York Times.

The piece described a set of documents, obtained by FOIA request, in

which the company and the agency exchanged views about soy leghemoglobin, and

whether it’s safe to eat.

This

stuff is only going to matter more down the line, as food technology continues

to evolve. It pays to get it right.

Make no mistake: This is a critical

distinction for Impossible. The company’s futuristic vegan burger is designed

to be meat-like enough to satisfy carnivores, down to the plant-based “blood”

it oozes when cooked medium rare. (Our review is here.) That added touch, which Strom called Impossible’s

“special sauce,” is made from the stuff the company discussed with FDA,

and took years and many millions to develop.

Though the original story, apparently

inspired mostly by dedicated anti-GMO activists, left a lot to be desired—as

you can read in Nathanael Johnson’s level-headed critique for Grist—the best part of the

story seems to have been swallowed in the subsequent debate. The real point

here is not the controversy. It’s what the back-and-forth reveals about how

cutting-edge plant-based technology works, and how scientists, for better or

worse, make their determinations about what’s safe or not. This stuff is only

going to matter more down the line, as food technology continues to evolve. It

pays to get it right.

First off, what is soy leghemoglobin,

and why is it in the Impossible Burger in the first place?

Leghemoglobin is a globin—one of a group

of globe-shaped proteins found in animals and plants. The globin you are

probably most familiar with is hemoglobin, which transports oxygen from your

lungs to the rest of your body, and which gives blood its red color.

Leghemoglobin is a plant globin, and soy leghemoglobin is the variant found on

the root nodules of the soy plant. There, it cooperates with colonies of

specialized bacteria to convert nitrogen into forms that the plant can use to

nourish itself. Anything left over when the plant dies goes back into the soil,

where other plants can use it. That’s why “nitrogen-fixing” plants like soy and

alfalfa are built into crop rotation schemes: They increase the available

nitrogen in the soil.

When

you heat up an Impossible Burger, the leghemoglobin releases its heme, just the

same way myoglobin in beef would release its heme.

The active ingredient of globins, the

thing that lets them work their magic with oxygen and nitrogen, is a molecule

called heme, which sits wrapped up in the amino acid chain of the globin. When

you heat up an Impossible Burger, the leghemoglobin releases its heme, just the

same way myoglobin in beef would release its heme. Iron-rich heme is part of

the characteristic flavor of meat—which is why Impossible wanted it in the

first place.

If it’s just part

of soy, what’s the problem? There are actually two problems. First, though humans

consume all sorts of globins in all sorts of forms, it appears that they

haven’t gotten around to eating soy leghemoglobin before. People eat soy beans,

of course, and they also consume a variety of plant products that contain

various sorts of leghemoglobin—think bean sprouts. Cows grazing on alfalfa

sometimes consume root and all, taking in leghemoglobin with no apparent ill

effects. But if people or livestock have been eating soy root nodules, they

haven’t gone public with it.

The second problem: The soy

leghemoglobin Impossible uses in its burgers doesn’t come directly from soy

plants. Instead, Impossible has implanted the soy gene responsible for creating

it in yeast cells—specifically Pichia pastoris, one of the

workhorses of biotech. The manufacturers brew up the modified yeast, much the

way you’d brew beer, but with the yeast releasing a globin instead of alcohol,

and then they filter out the yeast and other byproducts until the leghemoglobin

is about 80-percent pure.

The

lab did a literature search and found that not only was leghemoglobin not

associated with allergies, but the whole globin class was free from allergy

reports.

So is Impossible’s

leghemoglobin a GMO? Nope. It’s not an organism at all. It’s a protein produced by genetically

modified yeast cells. That’s an important distinction under current law, though

it doesn’t seem to matter much to the most ardent anti-GMO folks. For what it’s

worth, let’s not forget that modified cells—yeast, E. coli, Chinese hamster

ovary cells, and even human cancer cells—have been used for decades to produce

dozens of drugs that couldn’t be manufactured any other way using current

technology. Recombinant human insulin has largely replaced the earlier form

that was extracted from pigs, and we’ve seen the arrival of a host of

recombinant antibodies and other proteins to treat cancers, rheumatoid

arthritis, and other diseases. Like any drugs, they have their dangers, and

they’re expensive to develop and manufacture, but the overall safety of the

approach seems beyond question at this point. Which doesn’t mean that anything

you create through cell culture is automatically going to be safe.

So how do you tell

whether it’s safe? The big concern with proteins is food allergies. All of the “big eight”

allergens—eggs, milk, soy, fish, shellfish, wheat, peanuts, and tree

nuts—contain protein in varying amounts, and most are high in protein. So

Impossible hired an outside lab to analyze its leghemoglobin. The lab did a

literature search and found that not only was leghemoglobin not associated with

allergies, but the whole globin class was free from allergy reports, with the

exception of a single report of a reaction to cow myoglobin.

Impossible’s

leghemoglobin was 90 percent digested in 30 seconds and completely gone in a

minute.

Next it compared the structure of the

protein to analogous hemoglobins, known to be safe (from a variety of plants

and animals) and concluded that the soy leghemoglobin had no features—that is,

external structures it could use to hook itself onto cells in the body of

someone who had eaten an Impossible Burger) It compared the amino acid sequence

of Impossible’s protein with known allergens, looking for shorter stretches that

might be allergenic. They noted a stretch that bore a 35-percent resemblance to

a minor allergen found in potatoes, but concluded it wasn’t a strong enough

resemblance to cause problems.

Finally, they conducted a digestion

test. Apparently foods that cause an allergic reaction tend to be not very

digestible. If you find a protein that isn’t digested in a lab version of

gastric juices in eight minutes or so, that’s a red flag. Impossible’s

leghemoglobin was 90 percent digested in 30 seconds and completely gone in a

minute.

(Here’s a point worth noting: A protein

is a long chain of amino acids folded into a specific shape. It’s the shape

that gives it its ability to get things done in the body. A protein can be

“denatured”—unfolded and robbed of its bioactivity—by a number of factors

including heat and acidity. The leghemoglobin in the Impossible Burger is

supposed to denature during cooking: that’s the thing that releases the heme,

and it’s the whole point of including the leghemoglobin in the first place. So

most of the leghemoglobin is supposed to be biologically inactive by the time

it hits the gut. It’s highly digestible, but it’s not really supposed to get

the chance to be digested.)

Impossible

didn’t need FDA approval. Its leghemoglobin falls under the GRAS (generally

recognized as safe) regulations.

Meanwhile, the yeast and the nutrients

it feeds on are well known, widely used, and safe. The non-modified version of

the yeast is a permissible part of chicken feed, and modified versions have

been used in several FDA-approved drugs. The process of fermenting the yeast

and the techniques used to separate out the protein from the soup are well

known and understood. (In particular, in case you were wondering, the burger

doesn’t contain any of the yeast or the DNA the yeast once contained, though it

does contain small amounts of the proteins it naturally produces.)

And FDA said

what? You have to

understand two things: First, Impossible didn’t need FDA approval. Its

leghemoglobin falls under the GRAS (generally recognized as safe) regulations.

The company certifies the stuff as safe itself. It doesn’t have to consult FDA.

It did, though, and that was a smart idea. On the one hand, it helps head off

inevitable lawsuits. On the other, if Impossible wants to bring novel

ingredients to market, it needs to be good at GRAS, and FDA is happy to help.

Lots of companies seek FDA input on their GRAS filings.

Thing two: FDA is not known for saying,

“Yup, this application is perfect.” It tends to want a bit more. That’s what it

did this time, asking for more characterization of the yeast proteins and an

animal trial and some other minor modifications to the documentation. By FDA

standards, not a big deal at all, and very typical. The Impossible dream is

still alive.

If

you dive down into the documents, it really looks like a tale of conscientious

professionals on both sides doing their job in a confusing new realm.

So what should we

take away from all this? Honestly, not all that much. If you dive down into the documents,

it really looks like a tale of conscientious professionals on both sides doing

their job in a confusing new realm of activity, sometimes disagreeing,

sometimes talking at cross-purposes, but doing what they’re supposed to. (Could

there be hidden villainy here? Of course, but at least it’s not obvious. These

days that should count for at least something.)

If you weren’t aware of how important

molecular-level analyses have become to food safety, that’s something you want

to know—though I suspect not everyone will regard it as an improvement. If you

look at the GRAS process and are horrified at the idea of self-certification,

you might want to write your congressman, though realistically there are much

bigger fish to fry at FDA, and you might not want to distract those poor

overworked people. I personally note that the Times let us

down on this one. Their story kind of missed the boat.

One last little irony: In the end,

what’s going to confirm the safety of recombinant soy leghemoglobin (or

“modified soy protein,” as Impossible plans to call it) is a test where someone

will feed vast quantities of the stuff to lab rats—animals suffering to prove

the safety of a plant-based burger.

Picture a late-night meeting in the rat

lab. A grizzled old vet harangues his fellow rodents: “Rats gotta suffer so

cows can live,” he says. “Ain’t that always the way.”

Well, ain’t it?

Patrick Clinton is The Counter's contributing editor. He's also a long-time journalist and educator. He edited the Chicago Reader during the politically exciting years that surrounded the election of the city’s first black mayor, Harold Washington; University Business during the early days of for-profit universities and online instruction; and Pharmaceutical Executive during a period that saw the Vioxx scandal and the ascendancy of biotech. He has written and worked as a staff editor for a variety of publications, including Chicago, Men’s Journal, and Outside (for which he ran down the answer to everyone’s most burning question about porcupines). For seven years, he taught magazine writing and editing at Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism

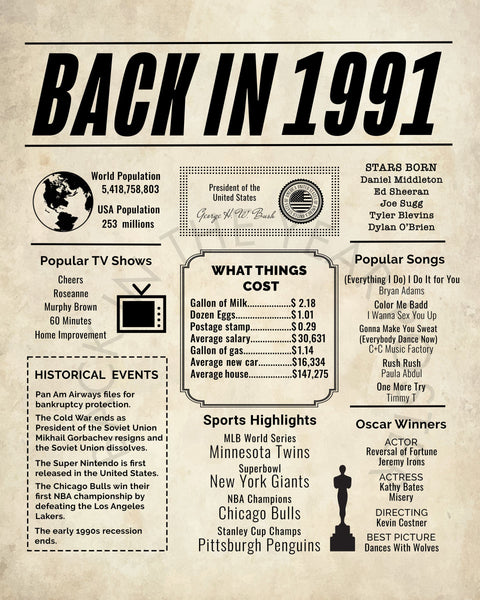

THE YEAR IN NUMBER - 1990

Continuing my series of the year in number.

At the end of 1989, I would get involved with a woman named Christine, who would be one of the most significant relationships of my life and would last almost a year, finally ending in early October of 1990.

I would finish my graduate school course work, though I would not finish my MA thesis until 1993 and though I finished my MFA project in 1994, I would not be able to secure faculty approval and my degree until 1997.

It was a good year for me, a pivotal year in my life, and for the world, which entered a new decade, the last of both the Twentieth Century and the second millennium.

A good year, but a transition year as I contemplated what to do after graduate school, even though I had to complete work, I was done with classes. When Christine and I broke up, I was devastated and would not say her name out loud for three years, instead using various nicknames I had invented for her. I felt betrayed, but then I had also betrayed her, in a sense, let her down. I still carry shame for my behavior that year, but I do think I have let myself off the hook for what happened.

1990 was an important year in the

Internet's early history. In the fall of 1990,

Tim Berners-Lee created the first

web server and the foundation for the

World Wide Web. Test operations began around December 20 and it was released outside

CERN the following year.

[2] 1990 also saw the official decommissioning of the

ARPANET, a forerunner of the Internet system and the introduction of the first content

web search engine,

Archie, on September 10.

[3]

September 14, 1990 saw the first case of successful somatic

gene therapy on a patient.

[4] http://www.thepeoplehistory.com/1990.html

1990 Following the Iraq invasion of Kuwait on August 2nd Desert Shield Begins as the United States and UK send troops to Kuwait. The US enters a bad recession which will have repercussions over the next few years throughout the world. This is also the year "The Simpsons " is seen for the first time on FOX TV. Following the Berlin Wall falling East and West Germany reunite. In technology Tim Berners-Lee publishes the first web page on the WWW and it shown that there is a hole in the Ozone Layer above the North Pole, also the First in car GPS Satellite Navigation System goes on sale from Pioneer.

http://www.thepeoplehistory.com/1990.html

1990 Following the Iraq invasion of Kuwait on August 2nd Desert Shield Begins as the United States and UK send troops to Kuwait. The US enters a bad recession which will have repercussions over the next few years throughout the world. This is also the year "The Simpsons " is seen for the first time on FOX TV. Following the Berlin Wall falling East and West Germany reunite. In technology Tim Berners-Lee publishes the first web page on the WWW and it shown that there is a hole in the Ozone Layer above the North Pole, also the First in car GPS Satellite Navigation System goes on sale from Pioneer.

https://rateyourmusic.com/list/RustyJames/songs-of-the-year-1990/

https://rateyourmusic.com/list/RustyJames/songs-of-the-year-1990/

[List18116] |

|

+1

+1

The Breeders

The Breeders

<-- 1989="" a=""> 1991-->

TEN BEST:

1. The Clean - "Diamond Shine"

2. The Charlatans - "The Only One I Know"

3. Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds - "The Weeping Song"

4. Sun City Girls - "The Shining Path"

5. Daniel Johnston - "Some Things Last a Long Time"

6. The Breeders - "Hellbound"

7. Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds - "The Ship Song"

8. Ride - "Drive Blind"

9. Daniel Johnston - "True Love Will Find You in the End"

10. Depeche Mode - "Enjoy the Silence"

Me and my then girlfriend in 1990

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2007.30 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1854 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6972643-1439835744-8441.jpeg.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64833626/ULlqdEa.0.jpg)