I posted about this situation once already.

Here: https://sensedoubt.blogspot.com/2018/06/hey-mom-talking-to-my-mother-1081.html

It's still happening. It's ongoing. It is not better.

Why aren't we all rising up against this?

Here's a reality check and a way for everyone to get involved.

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/06/why-its-fair-to-compare-the-detention-of-migrants-to-concentration-camps.html

THE WORLD

Not Every Concentration Camp Is Auschwitz

Why it’s fair to use the controversial phrase in the debate over U.S. immigrant detentions.

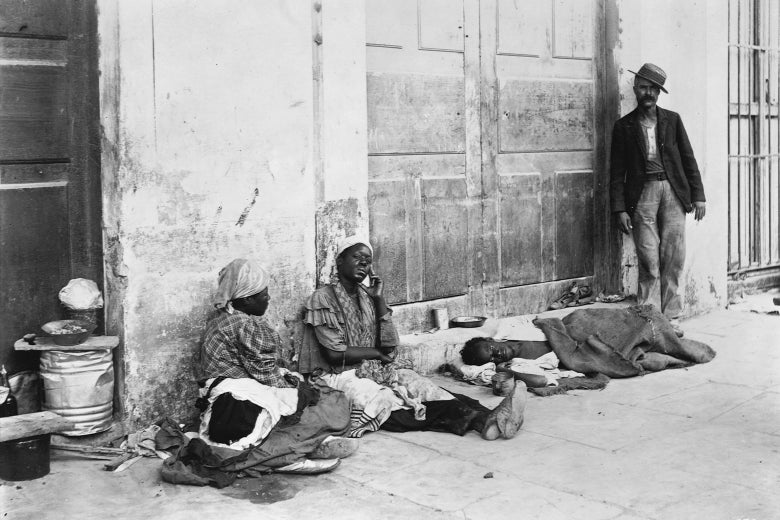

Poor refugees languish along the sidewalks of the reconcentrados, or concentration camps, of Havana.

Hugh L. Scott/Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

As one of the few journalists permitted to tour the government’s new internment camp, about 40 miles from the southern border, the New York Times correspondent tried to be scrupulously fair. Forcing civilians to live behind barbed wire and armed guards was surely inhumane, and there was little shelter from the blazing summer heat. But on the other hand, the barracks were “clean as a whistle.” Detainees lazed in the grass, played chess, and swam in a makeshift pool. There were even workshops for arts and crafts, where good work could earn an “extra allotment of bread.” True, there had been some clashes in the camp’s first days—and officials, the reporter noted, had not allowed him to visit the disciplinary cells. But all in all, the correspondent noted in his July 1933 article, life at Dachau, the first concentration camp in Nazi Germany, had “settled into the organized routine of any penal institution.”

This is not just a debate over semantics. How we categorize what is happening on the Southern border has everything to do with how the public and lawmakers will respond. That is why Trump administration officials have spent so much time trying to justify, lie, and shift blame for their new policy. Even Attorney General Jeff Sessions was forced to confront the concentration camp label on Fox News, which he tried incoherently to deflect. It’s obviously true that the Customs and Border Protection camp at Tornillo is no Auschwitz. But in dismissing any such historical comparisons out of hand, people are making the common mistake of reading history backward—looking only at the endpoint of a decadeslong process and ignoring the hard lessons humanity has learned, again and again, about where a policy like the one President Donald Trump and his supporters are now implementing can go. To see what I mean, you have to start at the beginning of the short and brutal history of the concentration camp.

Concentration camps were born out of war—not in Europe, but Latin America. In 1896, the Spanish empire was trying desperately to hold onto one of its last remaining colonies, Cuba. Independence wars had been raging there for three decades, and the fight wasn’t going well for Spain. Cuban revolutionaries, known as mambises, used ambushes, dynamite, and their deep knowledge of Cuba’s mountainous countryside to defeat colonial reinforcements. Believing the mambises’ advantage lay in the support and intelligence they received from rural communities, the island’s Spanish governor, Gen. Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, declared a new policy he called, euphemistically, reconcentración. Starting on Oct. 21, 1896, all civilians had to move behind the barbed wire of a handful of garrison towns controlled by the Spanish army. Any Cuban found moving freely or transporting food through the countryside was subject to execution. Knowing from the start that controlling the people required controlling information, Weyler also set out to aggressively censor any news critical of what he was doing.

The immediate result was a humanitarian catastrophe. Hundreds of thousands died of disease and hunger. An assistant U.S. attorney, Charles W. Russell, who toured the island in January 1898, told the New York Times he had seen “women and children emaciated to skeletons and begging everywhere about the streets of Havana” and cities where a fifth of the population had died in the previous three months. A previous Spanish governor-general had considered, then decided against, implementing the policy, knowing full well how brutal its effects would be. But Weyler was a hard-liner who saw no difference between mambises and Cuban civilians. He believed it was his duty to starve and demoralize the people into surrender. But the unintended consequences of reconcentración doomed his war effort. Even Cubans who had been ambivalent about independence now resolved to fight to the death, since that seemed to be the only option either way. Worse for Spain, the horrific reports scandalized Cuba’s neighbors in the United States. When the battleship USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor in February 1898, for reasons that still remain unknown, advocates for U.S. entry into the war only had to remind the public of the concentration camps to convince them the fading European power was capable of any evil.

But Americans would be next to put concentration camps into action. America’s entry into the Spanish-Cuban war mushroomed into a conflict on two continents, in which the United States annexed the Spanish territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, as well as previously independent Hawaii. (We effectively took over Cuba, too, and established a naval station at Guantánamo Bay, where a century later another infamous prison camp would be built.) U.S. officials were especially pleased with the capture of the Philippines, a resource-rich archipelago and source of new land on China’s doorstep. Filipinos were not as enthusiastic about one imperial overlord replacing another, and in 1899 a new war broke out. As a guerrilla insurgency mounted, Gen. James Franklin Bell ordered Filipinos herded into “protected zones,” where they would be prisoners of the U.S. Army. As in Cuba, violators would be shot. “While Army officers … claimed that the camps were healthy and not overcrowded,” the military historian Brian McAllister Linn has written, the cost in human suffering was “unquestionably high.” Americans were shocked to learn their forces had adopted the tactics of “Butcher Weyler.” An anti-imperialist senator read into the record an anonymous U.S. soldier’s letter describing an American concentration camp in the Philippines as “some suburb of hell.” Such reports helped undermine public support for the war, though the U.S. occupation of the Philippines would continue until after World War II.

Those first experiments helped establish a pattern that concentration camps would follow from then on: punishing civilians through mass detention and keeping them separate from society. Some observers, looking even further back, see foreshadows in other parts of history, including the breaking up of African and black American families during slavery, and the forcible displacement of Native Americans in the conquest of North America. But researchers note key, specific characteristics that set the concentration camp apart from other atrocities. Camps “require the removal of a population from society with all its accompanying rights, relationships, and connections to humanity,” author Andrea Pitzer writes in her 2017 book One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps. “This exclusion is followed by an involuntary assignment to some lesser condition or place, generally detention with other undesirables under armed guard.”

Removal, exclusion, denial of rights, mass detention—those tactics appeared again in the concentration camps Britain used to subdue the Dutch-descended Boers of South Africa in 1900, the imprisonment of “enemy alien” civilians on all sides in World War I, and the Soviet Union’s “corrective labor camps,” better known by the Russian acronym for the agency that administered them: Gulag. The United States used them on its own territory in World War II to imprison its own citizens of Japanese descent. Not yet fully discredited as a term, President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself suggested in a 1936 memo, written five years before the attack on Pearl Harbor that, should Japan strike, the Navy should prepare to put Hawaii residents of Japanese descent into a “concentration camp in the event of trouble.”

Which brings us back, historically speaking, to Nazi Germany. When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, he made no secret of his intentions to punish those he viewed as enemies, stamp out “undesirables,” and restore an imagined Teutonic greatness of the past. His government built its first concentration camp at Dachau just over a month after he became chancellor, to house political opponents of the new regime. Hitler knew the histories of Spain, Britain, and the United States. He had experienced the strategies of stripping citizenship from and forcibly imprisoning civilian populations during World War I. As he consolidated power, his staff ramped up pre-emptive arrests of anyone it deemed a target or threat, gaining confidence with every step.

It is important to understand that at the time, no one—not even Nazis—thought of such camps as places for extermination. Concentration camp—Konzentrationslager in German—was still a euphemism for forcible relocation and imprisonment, not murder. Even Auschwitz wasn’t “Auschwitz” at first—at least not in the sense we mean it today. When the Nazis built what would become their most notorious camp in German-occupied Poland, in 1940, it was used first for criminals, then expanded in anticipation of receiving Soviet prisoners of war. Despite seeming in retrospect to have been masterfully planned, historians believe, Nazi rule was mostly “chaotic and improvisatory,” taking advantage of circumstances as they arose. It was not until 1942, as the Nazi high command decided on a campaign of total genocide against the Jewish people, that camps were redesigned for mass murder. By the end, an initial population of a few thousand prisoners had ballooned to more than 1.3 million who passed through Auschwitz’s iron gates. Most would never return.

After the war, when the scale and horror of the genocide became clear to the world, anything associated with Nazism, including the term concentration camp, became an explosive insult. But as ridiculous as it would be for modern generals not to study tactics the Nazis used, it would be absurd for people today to ignore modern parallels with the most dangerous parts of history just because invoking them risks an imperfect comparison with the Holocaust. It’s an unavoidable fact that one of the major reasons the Nazis were able to kill so many people so easily, once they decided to, was the dehumanization and isolation created by their original concentration camps. Convincing a bureaucracy to massacre civilians is hard. Subjecting legal prisoners to Sonderbehandlung, or “special treatment,” as the killing of 6 million Jews and many others was officially called, was easier. As the philosopher Hannah Arendt, a refugee from the Nazis who spent time imprisoned in a French concentration camp before the German invasion, later observed: “All [concentration camps] have one thing in common: The human masses sealed off in them are treated as if they no longer existed, as if what happened to them were no longer of any interest to anybody, as if they were already dead.”

We are not there yet in this country. But what is happening near the Southern border is an unmistakable step down that road. In a Tuesday tweet defending his new policies, Trump blamed his political enemies, the Democrats, for being “the problem,” and accused them of conspiring with immigrants who want to “pour into and infest our Country.” He has repeatedly accused the people he is now detaining from across Central America, including presumably their children, of being reinforcements for a Salvadoran-American criminal gang. Forget for a second that illegal immigration to the United States has declined consistently since its peak more than a decade ago in 2007, that immigrants commit less crime than native-born Americans, or that most of the Central American children, women, and men imprisoned on the border are fleeing violence and poverty fueled by civil wars in which the United States played a leading role. Trump’s language, using a verb—infest—usually reserved for vermin or disease, is exactly in line with the kind of rhetoric and action that has defined concentration camps since 1896: the denial of rights, isolation, and concentration of undesirables by force.

Some may hope that these revitalized horrors will stay limited to the most vulnerable people—even including families who have risked everything to travel thousands of miles in hopes of reaching safety. But as the path from Spanish reconcentración to the gulags and death camps of the 20th century showed, once it is tolerated by society, a tactic does not tend to stay bottled up for long. Already the Trump administration has signaled its intention to begin stripping U.S. citizenship from those it feels don’t deserve it. Considering how even U.S. citizens deemed enemy combatants have already been treated under George W. Bush and Barack Obama, there is no telling what treatment people formally stripped of their most fundamental rights might expect if these new policies are allowed to continue.

Like with camps of the past, the Trump administration has tried to control the flow of information about what is going on inside the barbed wire. CBS News’ David Begnaud, one of the few allowed to see the cages at Central Processing Station “Ursula” in McAllen, Texas, reported after his visit that his team was not allowed to talk to anyone detained. Not only could the journalist not learn about the detainees’ experiences, but he was not allowed to put names or human faces on anyone being held. When information does get out, officials like Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen are instructing supporters not to believe it—a tactic that, as all authoritarian regimes have proved, often works.

Nonetheless, a clear majority of Americans are opposed to the most hard-line tactics being implemented on the border. Those numbers are likely to grow as stories mount about conditions in the sweltering heat at Tornillo and the baby jails of South Texas. Protests are underway, with nationwide marches planned for June 30. Some in the administration and its supporters are trying to stop the backlash by noting that inhumane deportation and detention practices existed under previous administrations as well—a fact that has been widely covered for years. But everyone builds on what comes before them.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 1906.29 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1456 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment