A Sense of Doubt blog post #1911 - Florian Schneider - KRAFTWERK - RIP

Welcome to a bonus music post for the second day in a row because of the passing of a great one.

I have a startling revelation of possible psychic reality to share. Read on.

I learned about the death of Florian Schneider via Warren Ellis' Orbital Operations newsletter delivered on 2005.10. Here's what he wrote and shared:

Noting also the passing of Florian Schneider, co-founder of Kraftwerk, one of the most important bands of the 20th Century. I was just talking to Gillen about being a kid in 1982 when the reissue of "Showroom Dummies" dropped right next to the Mobiles' "Drowning In Berlin" and thereby guiding me into a very specific path.

So here's the full version of "Autobahn," which features Schneider's flute. A central piece of 20th Century classical music.

Want to hear something weird? I started to listening to a lot of Kraftwerk last week inspired to do so for no discernible reason.

I dialed up Autobahn as I got ready in the morning last week... on May 6th, the day Schneider died.

Why did I suddenly know that I wanted to listen to Kraftwerk even though I did not learn of Schneider's death for four days?

Why did I suddenly know that I wanted to listen to Kraftwerk even though I did not learn of Schneider's death for four days?Not only did I listen on Wednesday May 6th. I continued to listen for the rest of the week.

I featured two posts on my T-shirt blog about Kraftwerk in 2013-14.

This post seemed a perfect fit in discussing my work as "grading robot," which is something I mention quite a lot on this and my previous blog.

T-shirt #36: Kraftwerk: We are the robots.

However, when I featured the next t-shirt, I created one of my most popular blog posts both for others and for myself:

T-shirt #97 - KRAFTWERK

In this post I asked the question, what albums have you listened to most often?

I consider this a different question than "favourite albums" because sometimes it's not quite the same as for one reason or another an album gets played over and over and over and becomes a frequent listen and yet not be a top ten favourite.

The first Kraftwerk album I owned. Trans-Europe Express, made that top ten list.

I love Kraftwerk.

I am sad to learn that another musical giant has passed away.

I will miss you, Mr. Schneider. Thankfully, your music endures.

Florian Schneider and Kraftwerk helped shape the sound of modern music

There are few bands whose influence was such that it can unequivocally be said that modern music would sound different without them. Kraftwerk, co-founded by Florian Schneider, whose recent death at the age of 73 was announced on May 6, was one such act. The band left an indelible imprint on the sound of popular music by bringing synthesised instruments to the forefront and electronics into the mainstream.

Schneider trained as a flautist at the Dusseldorf Conservatory, which might seem an odd background for a musician whose work did so much to shape the synth-pop and electronic dance music of the 1980s and beyond. But he and band-mate Ralf Hütter – an alumnus of the same music school – exemplified an exploratory approach to music making that traverses musical fields.

Emerging initially from an experimental milieu, their early albums were free-form improvisations that mixed electronic and traditional instruments. Alongside other German electronic acts, including Can and Neu!, they came to represent “krautrock” (as English critics dubbed it) or “Kosmische Musik” (‘cosmic music’, a term used by the German muscians).

The big breakthrough for Kraftwerk (the name means “power plant”) came with the release in 1974 of their fourth album Autobahn. The title track was a sonic depiction of the modernity of long-distance highway travel in their native Germany. Imbued with the sound effects of cars and horns, you could find distant echoes in the lyrics of the driving songs of Beach Boys and Chuck Berry. The album was a Top 10 hit, in Germany, the US and the UK, with a radio edit of the title track – 21 minutes long on the album – confounding expectations by charting as a single in the UK, US, Australia and the Netherlands.

Although some acoustic instruments could still be heard, Autobahn saw the band’s line-up stabilise around Schneider, Hütter and percussionists Wolfgang Flür and Karl Bartos. Its sound crystallised into something precise, evocative, human and yet simultaneously uncanny, laid over rhythmic grooves created with customised electronic instruments.

Influencing the influencers

While subsequent albums, including Radioactivity, Trans-Europe Express and The Man Machine, performed respectably – if not earth-shatteringly – in the commercial realm, Kraftwerk’s true impact was not so much about blazing a trail through the charts as expanding the parameters of popular music and opening up the ears of a generation of innovators to new possibilities. David Bowie’s late 1970s albums recorded in Berlin were heavily indebted to Kraftwerk, and he name-checked its co-founder on V-2 Schneider from Heroes.

Electronically synthesized instruments weren’t new, but had often been regarded as the preserve of experimenters on the commercial fringe, of the soundtrack artists in the more rarefied environs of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, or as a kind of novelty. Their presence in rock music was tolerated, but rarely celebrated or centralised until Kraftwerk.

Schneider and Hütter paved the way for pop that used electronics as a foundation, rather than a garnish, and cleared the way for the likes of Gary Numan, Depeche Mode and the Human League in the 1980s.

But their shadow was cast much wider than the straight line of synth-driven pop. The exactitude of their tracks, and sonic distinctiveness, made them ideal fodder for the sampling that was emerging as a recording practice. Their songs Numbers and Trans-Europe Express served as the lynchpin of Afrika Bambaata’s Planet Rock at the roots oft the roots of hip-hop. Likewise, techno pioneer Derrick May has been explicit about their extensive influence on the formation of the genre. He would recall their popularity with the originators of techno in Detroit: “They were doing this thing that was from another planet … everybody latched onto Kraftwerk.”

Enriching pop’s sonic vocabulary

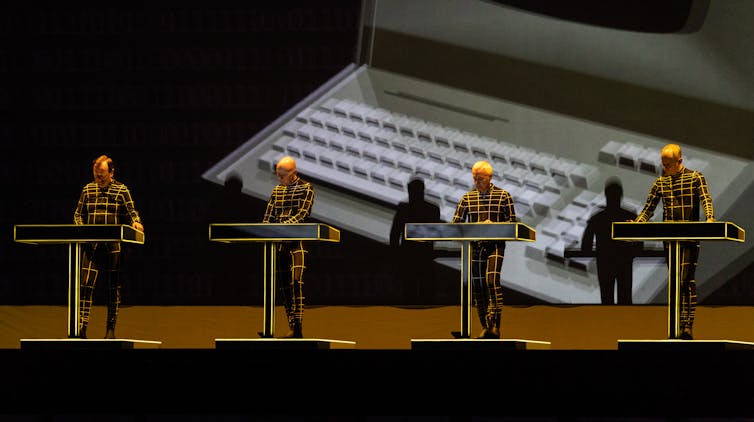

Key to their impact, and their work, was that they operated at a tangent to the pop world, as they had with the world of classical music. Their robotic stage act allowed them to eschew the celebrity game and the band, Schneider in particular, tended to be reticent about giving interviews in later years. Running their own studio: Kling Klang – their “electronic garden” as they called it – along with control of their business affairs allowed them to exercise aesthetic autonomy. As they told biographer Pascal Bussy in 2004:

We have invested in our machines, we have enough money to live, that’s it. We can do what we want, we are independent, we don’t do cola adverts, even if we might have been flattered by such proposals, we never accepted.

Their emphasis was on constructing sounds, first and foremost, with an omnivorous approach to source materials and subject matter. “We make compositions from everything,” Hütter told journalst Sylvain Gire. “All is permitted, there is no working principle, there is no system.” Mass appeal, it turned out, was a byproduct.

There’s a degree of irony in a band so tangentially concerned with pop so definitively reshaping it. Their singular approach has yet to be replicated, even as its echoes resound across pop, rock and dance music.

What makes them distinctive is that they didn’t just stand at a crossroads between different generic approaches, but uncovered those pathways, growing popular music’s sonic vocabulary and revealing its boundless capacity for incorporating new ideas.

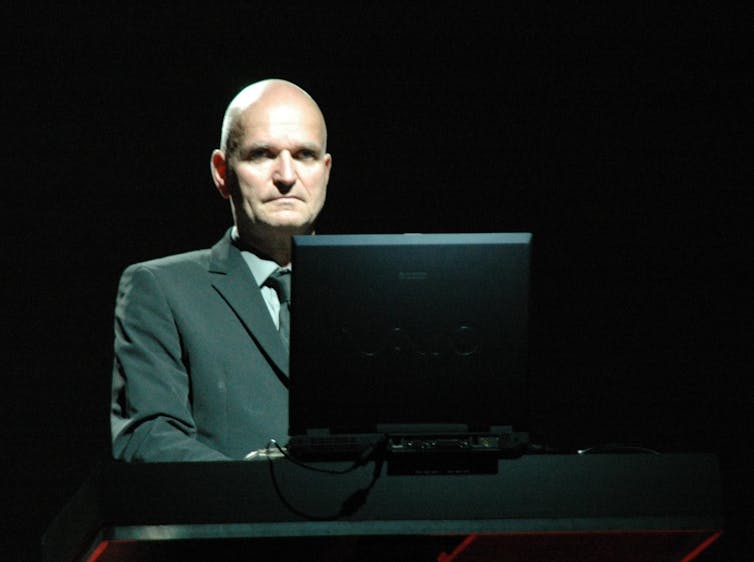

The ghost in the machine: Florian Schneider

Remembering a true pioneer.

Florian Schneider’s passing is a clear testament that Kraftwerk is so much more than the idea of ‘Man-Machine’. With the German outfit, he had an impact on modern music like very few have. By embracing the notion that electronic music was the creation of machines, they somehow humanized the concept more than most of us could. Kraftwerk unveiled the ghost in the machine.

Schneider bought his first synthesizer back in 1970, although he had been playing with Ralf Hütter since 1967, in Organisation (an improvisational music project). Gradually, the concept grew and morphed into what would become known as the first ‘versions’ of Kraftwerk. In 1974, their first material ‘Autobahn’ would be released to critical and popular acclaim, breaking into the top 5 of the BBC and Billboard charts.

But Kraftwerk and their music is just the beginning of this (neverending) story. Because the band is so much more than their own discography, or their iconic performances. Their influence has powered everything beyond modern electronica, techno, house, and even popular music, given the implementation of technology in the genre, making them, perhaps, the biggest contributors to electronic music.

Remember Them...

Europe Endless: Remembering Florian Schneider

Europe Endless: Remembering Florian Schneider

Jude Rogers , May 7th, 2020 07:07

Jude Rogers celebrates the life and times of a wry and humble musical pioneer dedicated to the reconfiguration of German identity

In 1977, as Trans-Europe Express clanged and glimmered, firing its way into the world, Florian Schneider graced the pages of New York’s Interview Magazine. Alongside Ralf Hütter, his musical collaborator of nearly a decade at that point, he answered Glenn O’Brien’s questions with sharpness, and occasional relish. Schneider told O’Brien he liked The Ramones, the Velvet Underground and The Doors: “They have some tradition behind them… they can go further now." What was his favourite sandwich? “We prefer cake.” Will he go bald? “Maybe.” Do you think that can be prevented? “I don’t care.”

There was often a wryness to Schneider in his words and in his image. It was there in his surprising grin at the end of Kraftwerk’s debut appearance on British television, on a 1975 edition of Tomorrow’s World. It was there in his hand-wiggling dance in the video to 'Showroom Dummies'. It was there in the way he rocked lipstick the best on the cover of The Man-Machine.

His humour also went beyond the existence of his band. Look online, and you’ll find a 2001 interview with Florian by German musician Uwe Schmidt, who had just made an album of Kraftwerk covers as Señor Coconut, in which he hides behind a false moustache. (“In 1947 in Mexico City, I devised the concept of humanoid sequencers,” Schneider hams.) There’s also his 2007 cameo as a wig-wearing double bassist in German film, Klassentreffen, alongside Klaus Schulze, playing a cover of 'Those Were The Days', or the way he promoted his and Dan Lacksman of Telex’s 2016 single, 'Stop Plastic Pollution', by wearing a jacket made out of recycled woven bags.

Back in the Glenn O’Brien encounter, he also explained where the concept of Kraftwerk came from in simple, magical terms: “We started with amplified instruments and then we found that the traditional instruments were too limited for our imaginations.” He also believed in technological progress, “but also we have to adjust our brains to this world”. Over the next few years, and in the decades that followed, many musicians, ravers, thinkers and fans adjusted their brains too, to follow him.

Florian Schneider-Esleben died last month, after a short time with cancer, at the age of 73. His sister and Wolfgang Flür posted pictures of him on social media last week, without comment. After a day of spiralling Twitter rumours, his family and one of his oldest friends confirmed his death yesterday.

For this fan, who still remembers Kraftwerk’s 1997 Tribal Gathering performance like a moment of pure, serene religious conversion, what seemed to ripple in Schneider’s presentation was always humanity, the element of Kraftwerk that is often forgotten. A crackle of electricity has always joined together humans and the machine. To make what David Bowie translated as folk music for the factories (“industrielle volksmusik”, they called it) also feels more compassionate and tender an act as the years roll on by.

Between 1970 and 2006 – his last official commitment with the band, at a gig in Zaragoza in Spain – Schneider helped give Kraftwerk their consistent, thrilling pulse. He lit the concert up in the most brilliant neon.

It wasn’t a particularly surprising journey for someone of Schneider’s family background, in hindsight, to devote his life to artistry, engineering and reconfiguring his German identity. Schneider’s great-grandfather, Peter, was a 19th century altar carver and sculptor who sent all seven of his sons to art school. One generation down, Schneider’s grandfather, Franz, built some beautifully stark early 20th century churches, and helped train Schneider's father, Paul, who became one of post-war Germany’s most celebrated architects.

Paul had to break his apprenticeship for military service in the second world war (he wasn't a Nazi party member). During pilot training in occupied France, he met several architects who rebuilt war-torn villages and towns, which interested him; after the war, he repaired buildings his father had started, and re-ignited the modernism that had been destroyed in its prime by the National Socialists in Germany. Two of his sisters also died in the war, during bombing raids. He was a man who wanted to rebuild German identity after the war ended, just as his son would, in new ways.

Schneider was born in the French occupation zone in Germany in 1947 (the family moved to Düsseldorf three years later). His father went on to design the passenger terminal for West Germany's biggest airport, Cologne Bonn, which would become a model for other international hubs (one wonders why Kraftwerk never went beyond cars and trains in their songs about international travel). He also worked with the artist Joseph Beuys, who by the late 1960s, was a huge artistic presence in the Düsseldorf Kunstacademie, an artist who talked about the potential of a gesamtkunstwerk, a total multi-disciplinary work of art with the potential to transform society.

Florian later took this idea and ran with it with the same zeal, and also took the roots of pre-war German culture, reigniting them to create a new future.

The connections with his father didn't stop there. Florian even played one of his first gigs with Joseph Beuys at the town’s Creamcheese Club, as part of the avant-garde ensemble, Pissoff (he was only 21). Schneider was studying flute at the Robert Schumann Hochschule at the time, pushing its tones to their limits with experimental techniques and delays. Soon after he formed Organisation with piano student Ralf Hütter, and such was the warm reception of experimentalism at the time, that by 1969 they’d release a record on RCA in the UK, Tone Float (it sold little; they were dropped shortly after). Propulsive rhythms underpinned its folkish psychedelia, giving clear clues about what they would become.

Schneider’s flute is all over Kraftwerk’s first three albums, despite his moves towards the future, including on Ralf And Florian’s glorious 'Tongebirge' (Mountain Of Sound). It’s also on the second side of 1974’s Autobahn, on 'Morganspaziergang' (Morning Walk), a conceptual opposite to the album’s whizzing title track. In this, birdsong and electronics start to fizz and sing together.

But in terms of the image and conceptual identity which would come to define Kraftwerk, Schneider was the first member of the band to mark himself out. On the original cover of Ralf And Florian, the pair are set against a passport curtain, just as they would be again, four years later, as part of a neat, pristine four-piece on the back of Trans Europe-Express. But in 1973, Ralf looks like a lank-haired late 60s throwback. Florian is, as he will be in the future, in a jacket, shirt and tie, wearing the same diamanté semi-quaver brooch on his lapel. He looks like an 80s synth-pop god arriving to the party ahead of time. (A live clip online from that period also shows the newly-recruited Wolfgang Flür, with long hair and moustache, like he’s wandered in from a Creedence Clearwater Revival convention.)

Schneider got much more obsessed with sonic possibilities as Kraftwerk developed as a band. He had the money from his father to buy groundbreaking electronic machines, like the Vako Orchestron and Synthia Vocoder used on 1975’s Radio-Activity. At this point, both were only a few years old.

He also talked about his innovative approach to the quality of sound. “We don’t make a distinction between an acoustic instrument as a source of sound and any sound in the air outside or on a manufactured tape,” he told Rolling Stone in 1975. ‘It’s all electric energy, anyway.” In an otherwise toe-curling encounter with Geoff Barton for Sounds the same year, he’s described listening to a vacuum cleaner being pushed back and forth over focusing on the whirring sound of the apparatus. Barton was one of many journalists who dismiss the band’s interest in electronics as clinical, manipulative German behaviour, but these days, their prose reads as lumpenly as the music these writers preferred. Kraftwerk’s records from the rest of that decade are all about texture which set out new template for the future, for which the man behind the vocoder deserves many plaudits.

By 1977, Kraftwerk’s influence also started to extend quickly beyond their original hit ('Autobahn' was described by many on its release as a bit of a novelty). Bowie’s 'V-2 Schneider' on “Heroes” remains the most notable tribute of those times, although the mention of Nazi bombs in its title seems ill-advised at best. Iggy Pop said in a 2009 BBC documentary that he played 'Geiger Counter' to help get him to sleep; he also once went asparagus shopping with Schneider, and they had a lovely time. Kraftwerk of course mentioned both artists on the title track of Trans-Europe Express, a rare foray on their part into the celebrity world.

Nevertheless, Schneider always remained humble when describing who Kraftwerk were doing. “We’re just private people,” he said in 1975. “In the evening we set up, turn on the knobs and play.” Such a statement must have sounded alien then, given the popularity of florid rock, and the virtuosity many people expected from artists to signify their talent. A few years later, after the three-chord DIY simplicity of punk and the dawn of hip hop culture, the idea of simply setting up some gear, turning the knobs and just playing sounded like something else: a manifesto for opportunities that were now available to all.

As their fame grew, Kraftwerk refined their image and ideas in albums that happened to have glossy, accessible titles. The concept of The Man-Machine spoke powerfully to young people excited about the emergence of personal computers and robotics in 1978. Computer World followed in 1981, effectively rubber-stamping synth-pop, and helping to invent techno, house, trance and everything else that came after it. Kraftwerk’s legacy was sealed. This was their present, and our future, and we all wanted to live in it.

After that moment, Schneider’s role in Kraftwerk became more indistinct (as it should be, one would argue, within a conceptual man-machine of a band). Other Kraftwerk albums were released: 1986’s lacklustre Electric Café, later rebranded under its original working title, Technopop; 1991’s underrated album of punchy re-edits, The Mix, and 2003’s Tour De France Soundtracks, finally bringing together tracks inspired by Hütter and Schneider’s mutual appreciation of cycling (in the early 80s, they were dropped off before gigs two hours early on the tour bus, so they could do the rest of the journey themselves).

Kraftwerk’s live shows also became more frequent after 1997’s Tribal Gathering, although Schneider was never a fan of the touring life. In retrospect, when he went on eBay in 2005 to list the customised vocoder he used on Autobahn, it felt like a symbolic act (Mute’s Daniel Miller won with his bid of $12,500). Schneider was announced as having left the band in 2008.

But Hütter had admitted that he and his friend hadn’t really worked together for “many, many years”; Schneider had been “working on other projects: speech synthesis, and things like that.” They weren’t in touch by then either, Hütter told Guardian journalist, John Harris. Harris then asked Hütter if he missed his friend. "Oh, what can you say?” the musician replied. “You have to ask him."

The fact that Florian’s death was confirmed to Billboard magazine yesterday by Ralf Hütter felt very moving. After all, Hütter has now been touring the world without his co-founder for over a decade, playing residencies at New York’s MOMA and Tate Modern, as well as revisiting smaller British venues in which they began as a band. The choice of words for this statement were uncharacteristically emotive, as if they had come from the roots of the band itself: “Hütter has sent us the very sad news that his friend and companion over many decades Florian Schneider has passed away…”

The statement reminded us that all lives have endings, but friendships rarely do. They may become detached, but they linger, they pulse, they never die. A quote of Schneider’s from the 1975 Rolling Stone also speaks volumes about how you’d imagine he might want to be remembered: not in the humanity or humility of who he was, but in the sounds he left to ripple way in the world.

“There is no beginning and no end in music,” Schneider said, wisely and truly, as ever. “Some people want it to end. But it goes on.”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2005.12 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1774 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment