|

| https://tidal.com/browse/playlist/33068580-c54b-4319-a48c-3a319b8c9986 |

A Sense of Doubt blog post #2365 - Hypnagogic Pop: Musical Monday for 2108.09

Welcome to the first of many installments about HYPNAGOGIC POP and other micro-genres of music, such as hauntology, IOP (Italian Occult Psychedelia). Witch House, Chillwave, Vaporwave, Glo-Fi, and more.

Hey, Mom! Talking to My Mother #279 - MUSICAL MONDAY: Music for April 11th

Hey, Mom! Talking to My Mother #573 - Kieron Gillen's Best of for 2016 - Musical Monday 1701.30.

Hey, Mom! Talking to My Mother #636 - Voodoo In My Blood - Musical Monday for 1704.03

A Sense of Doubt blog post #1896 - The Blackening and Isolation - More from the Orbital Operations vault.

The quotes below about hypnagogic pop demonstrate this, as they could well be describing hauntology:

Hypnagogic pop artists have a tendency to: “turn trash, something shallow and determinedly throwaway, into something sacred or mystical” and to “manipulate their material to defamiliarise it and give it a sense of the uncanny”. (Adam Harper, Dummy magazine)

The genre has been likened to: “sonic fictions or intentional forgeries, creating half-baked memories of things that never were—approximating the imprecise nature of memory itself” (Stone Blue Editors)

It has been described as “tak(ing) aspects of modern culture and nostalgia and transform(ing) them into new collective memories”. (Luna Vega)

Hypnagogic pop (abbreviated as h-pop) is pop or psychedelic music[5][6] that evokes cultural memory and nostalgia for the popular entertainment of the past (principally the 1980s). It emerged in the mid to late 2000s as American lo-fi and noise musicians began adopting retro aesthetics remembered from their childhood, such as radio rock, new wave pop, lite rock, video game music, synth-pop, and R&B. Recordings circulated on cassette or Internet blogs and were typically marked by the use of outmoded analog equipment and DIY experimentation.

The genre's name was coined by journalist David Keenan in an August 2009 issue of The Wire to label the developing trend, which he characterized as "pop music refracted through the memory of a memory."[7] It was used interchangeably with "chillwave" or "glo-fi" and gained critical attention through artists such as Ariel Pink and James Ferraro.[5] The music has been variously described as a 21st-century update of psychedelia, a re-appropriation of media-saturated capitalist culture, and an "American cousin" to British hauntology.

In response to Keenan's article, The Wire received a slew of hate mail that derided hypnagogic pop as the "worst genre created by a journalist".[5] Some of the tagged artists rejected the label or denied that such a unified style exists.[5] During the 2010s, critical attention for the genre waned, although the style's "revisionist nostalgia" sublimated into various youth-oriented cultural zeitgeists. Hypnagogic pop evolved into vaporwave, with which it is sometimes conflated.

Hypnagogic Pop

62 videos

Last updated on Jul 5, 2021

Avalons Messenger

Characteristics[edit]

Hypnagogic pop is pop or psychedelic music that draws heavily from the popular music and culture of the 1980s[8][6][9] – also ranging from the 1970s[10] to the early 1990s.[11] The genre reflects a preoccupation with outmoded analog technology and bombastic representations of synthetic elements from these epochs of pop culture, with its creators informed by collective memory as well as their personal histories.[12] Per the imprecise nature of memory, the genre does not faithfully recreate the sounds and styles popular in those periods.[1] In this way, hypnagogic pop distinguishes itself from revivalist movements. As authors Maël Guesdon and Philippe Le Guern write, the genre can be described as "revisionist nostalgia, not in the sense that 'everything used to be better' but because it rewrites collective memory with a view to being more faithful to an idea or a memory of the original than to the original itself."[13]

Examples range from "ecstatically blurry and irradiated lo-fi pop" to "seventies cosmic-synth-rock" and "tripped-out, tribal exotica".[16] Writing for Vice in 2011, Morgan Poyau described the genre as "making awkward bedfellows out of experimental music enthusiasts and weird progressive pop theorists."[17] He described a typical manifestation of the style as featuring long tracks "saturated with echo, delay, smothered guitars and amputated synths."[17] Critic Adam Trainer writes that, rather than a particular sound, the music was defined by a collection of artists who shared the same approaches and cultural experiences. He observed that their music drew from "the collective unconscious of late 1980s and early 1990s popular culture" while being "indebted stylistically to various traditions of experimentalism such as noise, drone, repetition, and improvisation."[18]

Common reference points include various forms of 1980s music, including radio rock, new wave pop, MTV one-hit wonders, New Age music, synth-driven Hollywood blockbuster soundtracks,[9] lounge music, easy-listening, corporate muzak, lite rock "schmaltz", video game music,[1] and 1980s synth-pop and R&B.[5][19] Recordings are often deliberately degraded, produced with analog equipment, and exhibit recording idiosyncrasies such as tape hiss.[11] It employs sounds that were considered "futuristic" during the 1980s which may appear psychedelic out of context.[11] Also common was the use of outmoded audio/visual technology and DIY digital imagery, such as compact cassettes, VHS, CD-R discs, and early Internet aesthetics.[15]

Origins[edit]

Background and hauntology[edit]

In the 2000s, a wave of retro-inspired home-recording artists begun dominating underground indie scenes.[20] The emergence of Ariel Pink's Haunted Graffiti, in particular, prompted journalistic discussion of the philosophical concept of hauntology,[21] most prominently among the writers Simon Reynolds and Mark Fisher.[22] Later, the term "hauntology" was described as a British synonym for hypnagogic pop,[3] while hypnagogic pop was described as an "American cousin" to Britain's hauntological music scene,[23][1][24]

Todd Ledford, owner of the music label Olde English Spelling Bee (OESB), attributed a correlation between the proliferation of hypnagogic pop and the rise of YouTube.[25] Reynolds attributed the origins of hypnagogic pop to Southern California and its culture. Trainer disagreed with Reynolds' assertion and said the style "arguably" emerged from numerous simultaneous scenes inhabited by artists working in a diverse form of "post-noise neo-psychedelia".[26] Pitchfork's Marc Masters offered that it may have originated "less [as] a movement than a coincidence".[27] The music was often issued in the form of limited-edition cassettes or vinyl records before reaching a wider audience through blogs and YouTube videos.[9]

Formative artists

Ariel Pink gained recognition in the mid 2000s through a string of self-produced albums, pioneering a sound that Reynolds called "'70s radio-rock and '80s new wave as if heard through a defective transistor radio, glimmers of melody flickering in and out of the fog".[28] He identified Pink and the Skaters as the "godparents of hypnagogic",[29] but singled out Pink as the central figure to what he calls the "Altered Zones Generation", an umbrella term he designed for lo-fi, retro-inspired indie artists who were commonly featured on Altered Zones, an associate site for Pitchfork.[20][nb 2] Tiny Mix Tapes' Jordan Redmond wrote that Pink's early collaborator John Maus was also placed "at the nexus of a number of recent popular movements" including hypnagogic pop, and that Maus was as "much of a progenitor of this sound as Pink, even though Pink has tended to be the headline-grabber."[31]

R. Stevie Moore and Martin Newell were earlier artists who anticipated Pink's sound.[20] Matthew Ingram of The Wire recognized Moore's influence on Pink and hypnagogic pop: "through his disciple ... he has unwittingly provided the [genre's] template".[32][nb 3] Another precursor to the genre was Nick Nicely and his 1982 single "Hilly Fields (1892)". Red Bull Music's J.R. Moore wrote that Nicely's "uniquely haphazard DIY aesthetic" and contemporary take on 1960s psychedelic pop "basically invented the sound of the 2000s Hypnagogic Pop movement decades beforehand."[34][nb 4]

The Skaters were a noise duo consisting of James Ferraro and Spencer Clark, and like Pink, were based in California.[35] In the mid-2000s, they released dozens of CD-Rs and cassettes of psychedelic drone music, after which Ferraro and Clark each pursued solo outings.[11] From 2009 to 2010, Ferraro's music evolved to be increasingly rhythmic and melodic, as Trainer describes, "an oversaturated sonic palette of cheesy pop reminiscent of early video game soundtracks and 1980s Saturday morning cartoons."[36]

Complex contributor Joe Price felt that the h-pop movement was "birthed" by Ferraro and "the vastly overlooked [Missouri artist] 18 Carat Affair".[37] In Reynolds' description, "other rising figures" from the original California scene included Sun Araw, LA Vampires and Puro Instinct. He added: "Other key hypnagogues such as Matrix Metals and Rangers reside elsewhere but seem SoCal in spirit."[9] In a 2009 interview, Daniel Lopatin (Oneohtrix Point Never) stated that Salvador Dalí and Danny Wolfers were the "godfathers of hpop". He identified other progenitors to be DJ Screw, "retro kids", Joe Wenderoth, Autre Ne Veut, Church In Moon and DJ Dog Dick.[38]

more at - HYPNAGOGIC POP.

Cultural interpretations[edit]

Simon Reynolds described hypnagogic pop as a "21st-century update of psychedelia" in which "lost innocence has been contaminated by pop culture" and hyper-reality.[9] He notes a particular concern with the "scrambling of pop time", suggesting that "perhaps the secret idea buried inside hypnagogic pop is that the '80s never ended. That we're still living there, subject to that decade's endless end of History."[9] Guesdon and Le Guern posit that "the hypnagogic movement can be seen as an aesthetic response to the growing feeling that time is speeding up: a feeling that often proves to be one of the fundamental components of advanced modernity."[13]

Adam Trainer suggested that the style allowed artists to engage with the products of media-saturated capitalist consumer culture in a way that focuses on affect rather than irony or cynicism.[15] Adam Harper noted among hypnagogic pop artists a tendency "to turn trash, something shallow and determinedly throwaway, into something sacred or mystical" and to "manipulate their material to defamiliarise it and give it a sense of the uncanny."[10]

LINK: The Best Hypnagogic Pop Albums of All Time

|

| James Ferraro Touch Screen Splatter Punks of Digital Tokyo (In production, due to be completed in 2013) |

‘Hypnagogic Pop’ and the Landscape of Southern California

A 21st-century update of

psychedelia and a new generation of American lo-fi musicians who channel the

1980s sounds of mainstream radio rock, New Wave mtv pop, sedative New Age and

the peppy synth-driven soundtracks of Hollywood blockbusters

IN FRIEZE | 01 MAR 11

Coined by The Wire magazine’s David Keenan in 2009, ‘hypnagogic pop’ is a term for a new generation of American lo-fi musicians who channel the 1980s sounds of mainstream radio rock, New Wave mtv pop, sedative New Age and the peppy synth-driven soundtracks of Hollywood blockbusters. Released as limited-edition cassettes and vinyl but reaching a larger audience through blogs and YouTube videos, hypnagogic pop shimmers with motifs and textures that flash back to the slick hits of artists such as Hall & Oates and Don Henley. The musical and conceptual pioneers of this movement, Ariel Pink and James Ferraro, are both based in LA, as are other rising figures like Sun Araw, LA Vampires and Puro Instinct. Ferraro’s frequent collaborator Spencer Clark lives in another sun-baked Southern California sprawl town, San Diego. Other key hypnagogues such as Matrix Metals and Rangers reside elsewhere but seem SoCal in spirit.

Hypnagogic is the term for a state between being awake and falling asleep, associated by some with hallucinations that are hyper-real rather than surreal. Life in LA – also the title of an Ariel Pink song, as it happens – does lend itself to a kind of ‘wide asleep’ trance, as your gaze falls under the sway of the sheer numbing beauty of the landscape and the weather – the way a certain slant of late afternoon light makes lawns glow eerily. Even the less attractive aspects of this town – strip-mall vistas that seem so desolate in the non-Sun Belt zones of the US – get softened by the bright lit blue skies (another Pink song) and by the peculiar mingling of utterly denatured built-up zones with outright wilderness.LA is a city where Spectacle (in the Situationist sense) and the Spectacular (in the geological sense) are freakily entwined. As a recently arrived resident, I’m yet to tire of the juxtaposition of, say, an In-N-Out Burger drive-thru against the near-kitsch splendour of the San Gabriel Mountains. ‘Collage reality’ is how Spencer Clark describes the effect, adding that his music is a byproduct of living in ‘a zone that has beaches and mountains and hills as well as skyscrapers […] A lot of my music I see as landscape music.’

Hypnagogic is a 21st-century update of psychedelia. Like its 1960s antecedent, it looks to the West Coast, but its primary focus is LA rather than San Francisco; ’60s anti-urbanism has been supplanted by an ambiguous exaltation of suburbia. Hypnagogic retains the original psychedelia’s fixation on childhood but this lost innocence has been contaminated by pop culture: mtv one-hit wonders and ’80s cartoons replace the Winnie-the-Pooh and Alice in Wonderland references of Jefferson Airplane. The scrambling of pop time is a culture-wide phenomenon in the West, but it feels unusually strong in LA, where pop radio is dominated by old music: classic rock, New Wave and eclectic stations like Jack fm that mimic a 40-something’s iPod Shuffle. Flicking between stations, there’s a visual analogue to what you hear in the endless interplay of different eras of commercial signage and shop-front décor. In no other city have I had such an overwhelming sense of the erosion of a cultural timecode, that pulse that once synchronized the sectors of the contemporary scene (fashion, design, music, etc.) and constructed a sense of epoch.

Last year James Ferraro posted a YouTube video to promote his albums Wild World (2009) and Feed Me (2010), but which also served as preview of a full-length movie he’s making (Touch Screen Splatter Punks of Digital Tokyo due to be completed in 2013). The excerpt concatenated low-budget horror (Ferraro as decomposing corpse, TV dinners that come alive) with archival snippets of President Reagan and hand-held footage of Hollywood street scenes: leather-booted vamps from the Valley, businesses like Happy Nails and LA Tanning, gossip mags with ‘plastic surgery shockers’ cover stories. By email, Ferraro told me about his future projects, the most striking of which is a ‘live webcam water birth viewable online with interactive chat functions’. The idea was inspired by witnessing ‘a lady give birth in a Starbucks at The Grove in Hollywood, surrounded by smart phones and digital cameras. So you see this reality will always be a part of my work.’This reality is hyper-reality. In what may be a deliberately ’80s-retro gesture, Ferraro frequently sounds like he’s channelling Jean Baudrillard, talking of wanting to be ‘simulacra’s paintbrush’. Other ’80s totems spring to mind during his patter: David Cronenberg, when Ferraro talks of getting burned out on Hollywood, recharging his batteries in more earth-toned, bohemian zones of LA like Eagle Rock, then ‘jumping back into the movie screen’; Jeff Koons, for the aesthetic of kitsch sublime running through Ferraro’s work and the inscrutable ingenuousness with which Ferraro delivers his lines. He says he moved to LA to become an action movie star, just like his heroes Jean-Claude Van Damme and Sylvester Stallone.

Also part of this iconic cluster is J.G. Ballard: Ferraro echoes the late novelist when he talks of movie stars as modern deities embodying qualities that human beings have admired since the dawn of time. High Rise (1975) and Kingdom Come (2006) spring to mind when you read the sleeve note description of ‘Headlines (Access Hollywood)’ from 2010’s album Last American Hero. The song is about people who get trapped in Costco (a bulk-buy, budget-price hypermarket) and devolve into a mutant tribe whose children, ‘born within the settlement’, grow up with ‘no conception of a world beyond’. Not that you can really derive this from the track, a frayed instrumental that resembles the blues if its foundational figure wasn’t Robert Johnson but Harold Faltermeyer of ‘Axel F’ and Beverly Hills Cop (1984) fame. Elsewhere in Ferraro’s most SoCal-themed releases – Wild World, On Air (2010), and the brand-new Nightdolls with Hairspray (2011) – he explores a sound that draws on ’80s rock at its most artificial: shrill, garish textures like you might at hear in a guitar shop where some Eddie Van Halen wannabe is trying out too many effects pedals at once.

Like a modern-day Devo, Ferraro never lets on whether he’s reviling or revelling in the decadence and grotesquerie of US culture. The cover of Last American Hero is a glossy photograph of a Best Buy store, described in the sleevenotes as ‘the modern Gomorrah temple’. But Ferraro also enthuses about ‘the primal fantasies and fetishes, hedonistic urges, mouth watering narcissism and dreams manifested into plastic surgery in our digital age Whole Foods candy land’. Shopping malls, celebutainment, cosmetic surgery, a consumer culture orientated around bipolar rhythms of bulimic bingeing and anorexic/aerobic purging – all this really took off in the ’80s. (And was taken to the extreme in California – for Baudrillard, America’s vanguard, a sort of hyper-America.) Perhaps the secret idea buried inside hypnagogic pop is that the ’80s never ended. That we’re still living there, subject to that decade’s endless end of History, killing time as we wait for something (seismic, subaltern) to rupture the dream.

Hypnagogic pop artists have a tendency to: “turn trash, something shallow and determinedly throwaway, into something sacred or mystical” and to “manipulate their material to defamiliarise it and give it a sense of the uncanny”. (Adam Harper, Dummy magazine)

The genre has been likened to: “sonic fictions or intentional forgeries, creating half-baked memories of things that never were—approximating the imprecise nature of memory itself” (Stone Blue Editors)

It has been described as “tak(ing) aspects of modern culture and nostalgia and transform(ing) them into new collective memories”. (Luna Vega)

Hypnagogic Pop Dreams

https://ayearinthecountry.co.uk/a-lineage-of-spectres-part-2-hauntology-hypnagogic-pop-synthwave-and-the-creation-of-mystical-half-hidden-worlds-wanderings-explorations-and-signposts-2152/

A Lineage of Spectres Part 2 – Hauntology, Hypnagogic Pop, Synthwave and the Creation of Mystical Half-Hidden Worlds: Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 21/52

In Part 1 of this post I discussed how hauntology and its sense of creating parallel worlds via the hazy misremembering of past eras’ source material could be seen as being part of a broader continuum and lineage.

Part of that broader lineage or continuum could be considered to include hypnagogic pop, with which it shares some notable signifiers and cultural approaches.

The quotes below about hypnagogic pop demonstrate this, as they could well be describing hauntology:

Hypnagogic pop artists have a tendency to: “turn trash, something shallow and determinedly throwaway, into something sacred or mystical” and to “manipulate their material to defamiliarise it and give it a sense of the uncanny”. (Adam Harper, Dummy magazine)

The genre has been likened to: “sonic fictions or intentional forgeries, creating half-baked memories of things that never were—approximating the imprecise nature of memory itself” (Stone Blue Editors)

It has been described as “tak(ing) aspects of modern culture and nostalgia and transform(ing) them into new collective memories”. (Luna Vega)

Although possibly more overtly replication than refracting orientated, the music/cultural movement of synthwave which began to develop around a similar time as hypnagogic pop, could be seen as a further example of this broader lineage.

As with hauntology, both synthwave and hypnagogic pop essentially create/recreate their own parallel worlds and cultural visions which draw from filtered, sometimes reinterpreted cultural memories.

(A brief definition of synthwave from Wikipedia: “Synthwave – also called outrun, retrowave and futuresynth – is a genre of electronic music influenced by 1980s film soundtracks and video games. Beginning in the mid 2000s, the genre developed from various niche communities on the Internet, reaching wider popularity in the early 2010s. In its music and cover artwork, synthwave engages in retrofuturism, emulating 1980s science fiction, action, and horror media, sometimes compared to cyberpunk. It expresses nostalgia for 1980s culture, attempting to capture the era’s atmosphere and celebrate it.”)

In contrast to hauntology and hypnagogic pop, synthwave has a more noticeably defined and identifiable aesthetic – in particular retro futurist lightgrids and a Tron-esque aesthetic frequently appear.

As part of the above lineage of hazy parallel world misrememberings and reimagining of past eras, in terms of cinema you could also look towards the likes of Panos Cosmatos’ Beyond the Black Rainbow film, which I have written about at A Year In The Country before; it draws from 1980s film, video and music culture and has been described as a “Reagan era fever dream” and creates a sense of being some lost, almost hallucinogenic cultural artifact from a darkly refracted dreamscape vision of that era.

At points, particularly in its driving sequences and some of the lighting structures of the underground complex which are portrayed in the film, aesthetically it intersects to a degree with some elements of synthwave, although in a possibly darker and less escapistly kitsch manner.

Hauntology and hypnagogic pop tend to have more heavyweight theoretical, philosophical and cultural viewpoints either attached to or underpinning related work (sometimes by its creators, sometimes by third party observers and critics), while synthwave seems to also be a possibly more overtly purely escapist form of cultural entertainment.

Which brings me to some of the possible underlying impetuses for and/or attraction of some of such work.

The roots of the word hauntology come from in part Jacques Derrida’s observations that in late-stage capitalism (ie today and in relatively recent decades) society would be drawn to the nostalgic, the familiar and to become haunted by spectres of its own past.

Spectres is an interesting and possibly apposite word to use and it connects back to the just quoted hypnagogic pop artists’ attempt to create “something sacred or mystical”.

What hauntological work in particular seems to be in part is an attempt to reintroduce a sense of the unknown, the partially hidden, of the mystical into a world which is often focused on scientific and economic rationality which has little time for that which cannot be “logically” explained, categorised and organised by and within its own structures, theories and tenets/beliefs.

In part such attempts to reintroduce a sense of the mystical can also be connected to the confluence and interaction of otherly pastoral, wyrd or “eerie” Britain orientated work and hauntology, which as Robert Macfarlane has said could be seen as being:

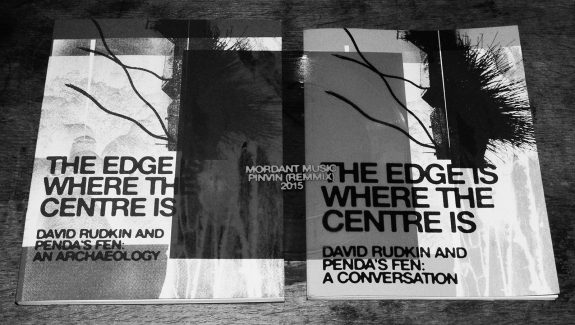

“… an attempt to make sense, explain, account for and possibly act as a respite, allow refuge from and act as a bulwark against the current dominant capitalist system: in part a utilising or reconfiguring of the spectral or preternatural as a form of expression, exploration and escape from related turbulence and pressures.” (Quoting myself quoting Robert Macfarlane in The Edge Is Where The Centre Is book on Penda’s Fen.)

So, hauntology could be seen as a form of exploring or creating modern-day magic, the mystical, the supernatural, spectres and hauntings…

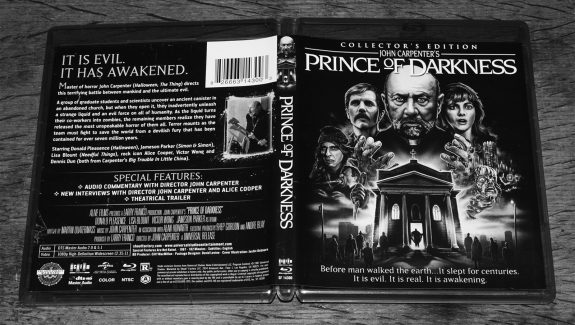

Which brings me to John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness film from 1987… more of which coming soon…

Elsewhere:

Hypnagogic pop at Wikipedia

Synthwave at Wikipedia

Elsewhere at A Year In The Country:

1) Day #149/365: Phase IV – lost celluloid flickering (return to), through to Beyond The Black Rainbow and journeys Under The Skin

2) Day #162/365: Hauntology, places where society goes to dream, the deletion of spectres and the making of an ungenre

3) Day #183/365: Steam engine time and remnants of transmissions before the flood

4) Day #255/365: Beyond The Black Rainbow; Reagan era fever dreams, award winning gardens and a trio of approaches to soundtrack disseminations… let the new age of enlightenment begin…

5) Audio Visual Transmission Guide #9/52a: Beyond The Black Rainbow and Phase IV

6) anderings, Explorations and Signposts 2/52: Penda’s Fen and The Edge Is Where The Centre Is – Explorations of the Occult, Otherly and Hidden Landscape

7) Chapter 3 Book Images: Hauntology – Places Where Society Goes to Dream, the Defining and Deletion of Spectres and the Making of an Ungenre

8) Wanderings, Explorations and Signposts 20/52: A Lineage of Spectres Part I – From “Traditional” Hauntology to Hypnagogic Pop

https://mrnonsense.bandcamp.com/

https://www.facebook.com/Chillwave.GloFi.HypnagogicPop/

https://cotmasounds.wordpress.com/2013/10/25/instant-nostalgia-how-hypnagogic-pop-is-redefining-culture-why-you-should-be-listening-to-ducktails/

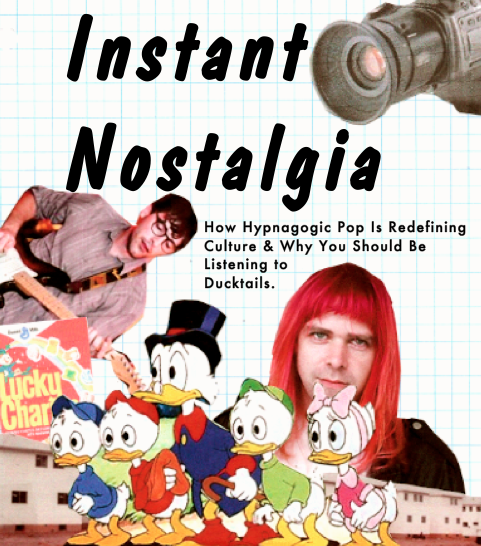

INSTANT NOSTALGIA: HOW HYPNAGOGIC POP IS REDEFINING CULTURE & WHY YOU SHOULD BE LISTENING TO DUCKTAILS

Instant Nostalgia:

How Hypnagogic Pop is Redefining Culture & Why You Should Be Listening to Ducktails

by Zachariah Webb

In an era where every blogger with a dictionary is apt to cobble together adjectives in order to pin down an artist’s particular sound, a proliferation of obscure subgenres of “indie pop” have come to resemble the inaccessible and incoherent family tree of a soap opera. However, one instance of a subgenre materializing from the world of music criticism—hypnagogic pop—is representative of not only a minor music trend of hazy, dream-like nostalgia, but a far-reaching cultural perception.

In 2009, The Wire’s David Keenan coined the term “hypnagogic pop” to encapsulate a recent trend of underground American musicians utilizing lo-fi, reverb saturated sounds and revisionist nostalgia to construct an aural aesthetic of a golden epoch long since faded. Defined as, “relating to, or occurring in the period of drowsiness immediately preceding sleep,” hypnagogic brings to mind the hazy, dreamlike quality of memories brought to life in the state between waking and sleeping.

Hypnagogic pop (or h-pop), accordingly, is a subgenre with loose boundaries, as it deals more so with the aesthetic similarities of artists prone to lo-fi productions, a clear dependence on the past, and DIY techniques of distribution. While artists like LA Vampires, Ariel Pink, Pocahaunted, Ducktails & James Ferraro clearly fit this approach, there is some crossover with its arguable spawn—chillwave, made famous in the mid to late 00s by Washed Out, Toro y Moi & Neon Indian.

The particular sound of h-pop is heavily influenced by the decade in which many of these artists were watching Saturday cartoons and drowning themselves in the synth-driven scores of early video games: the eighties. Drawing on this past, much music tagged as h-pop would sound perfectly at home blasting through an FM radio station forever lost in 1984. The woozy sounds of Ariel Pink and Ducktails seem to draw unironically on a wealth of old children’s cartoons and eighties chart pop-rock, distorting it into a hazy, psychedelic sound evocative of the surreal slant of late afternoon sun passing through the blinds.

The synth-driven hook of Ariel Pink’s eerie, “Fright Night (Nevermore),” would, for instance, be equally at home in an eighties public service announcement about the perils of stranger danger or on a millennial’s playlist for a retro Halloween party, while the bright neon vibes of “Beverly Kills” could just as easily be the unreleased theme to a Beverley Hills Cop remake. His music lends itself to a kind of “wide asleep” trance, where one’s far off gaze fluctuates between warm visions of the past and the smog-ridden sky. Occupying the ethereal space between the past and present, Ariel Pink especially seems to rely on borrowed elements from his childhood in the eighties to articulate a sense of overwhelming nostalgia felt by the present.

Another prominent artist of the loose-knit h-pop family committed to evoking images of “back then” is Ducktails. Inspired by the eighties Disney cartoon of the same name, Ducktails began as the side project of Real Estate drummer, Matt Mondanile, in a Northampton tool shed during his last year of college and has since spawned several albums and EPs. Several of which were, naturally, released exclusively on cassette. Dominated by airy vibes with a psychedelic slant, Mondanile’s work reveals what Pitchfork deems “a reflexively hazy attitude toward the way of the world” and drips with nostalgia for summers past. Ducktails is, therefore, a prime example of the blending of genres, influences & electronic textures paramount to hypnogogic pop. While distinctly more polished than his lo-fi earlier releases like Landscapes, Mondanile’s most recent effort, Wish Hotel is still a dreamy five-track soundtrack to an overcast afternoon. Check out “Honey Tiger Eyes,” the lead single from Wish Hotel, below:

Rejecting the modern ease of high-end production values, many h-pop artists turn to recording music videos with old VHS camcorders—splicing together old cereal commercials and snippets of MTV as a visual representation of their collaged sound. Distorted images and odd color saturation aid in a surprisingly cohesive articulation of a nostalgic aesthetic through both the music and its visual representation.

This piecing together of multiple influences and reference points from a familiar culture is often grounds for critique, as some claim that the work falling under the h-pop umbrella is merely a derivative collage as opposed to a genuine synthesis of their influences. With such an intrinsic relationship to the cultural products of the past, some claim it ultimately denies the possibility of creating anything original.

The authenticity of these artists is subsequently called into question. This critique fails to acknowledge the inherently derivative nature of art. Inspiration must come from somewhere, and as long as the primary source isn’t copied wholesale—but rearranged and distorted—it is authentic art. The artistic mutilation of these sources is often to the degree that an entirely new entity has been created. It’s “pop in a pop art kind of way,” remarked James Ferraro in an interview with Dummy Magazine. Our modern world is one of such hyper-connectivity that we are allowed a previously unimaginable vantage point on all that has come before us. H-pop makes use of that to mesmerizing effect.

Hypnagogic pop, or “the music of nostalgia,” can be easily applied to a broader portion of music today—everyone from the oft-criticized sixties vibes of Lana Del Rey to Bethany Cosentino’s sunny distortions of the California coast and the haze-crazy psychedelic work of Bibio. These artists are at their best when channeling revisionist nostalgia as an approach to songwriting. So what may initially appear a purposefully obscure subgenre is actually a rather on-point analysis of today’s music scene.

This highlights a major parallel between the philosophy at play in hypnogogic pop and the larger societal shift towards an instant nostalgia for the past. The aesthetic and inspiration behind h-pop is perhaps the most accurate representation of our modern cultural perception, which has become a pop-art collage of all that has come before. There is a proliferation of individuals on the Internet (i.e., Tumblr) revising and reconstructing bits of past cultural aesthetics in order to create new perceptions of those moments in time. We’ve turned into a vinyl-collecting, Instagram-filter-crazy bunch—cultural hedonists dining, seemingly unaware, on the best the last century has to offer us. We have become convinced that past decades were inherently better. And while that may not be entirely true, this impulse to rework and romanticize has led to a great aural aesthetic.

As this trend of revisionist nostalgia continues grow in its domination of cultural expression, & a whole horde of bloggers & musicians are busy reconstructing the appearance and sound of a past culture at once, the actual past itself begins to change. The primary source for future generations becomes vague and inaccessible. With the erosion of decade barriers between styles of the past and present, we have entered into a hyper-reality of musical freedom, where the lines between the reality of decades past and our modern reinterpretation of it become almost meaningless. What’s more “authentic” to the sound of the eighties, is it the opening theme of Beverly Hills Cop or “Beverly Kills” by Ariel Pink? What does “authentic” even mean to us as a culture anymore?

This debate—which would quickly dissolves into rhetoric more inaccessible than sadcore—ignores the possibilities of a continual reinterpretation of the past, all fed through a nostalgic golden haze and played back over a fuzzy cassette tape by the likes of Ducktails and Ariel Pink.

Hypnagogic Pop: A Contemporary History of Underwater Pop Nostalgia (2006-'20)

A list by novocaine69

Categories: Genre, 2000s, 2010s, Obscure

----

A couple of years ago a RYMer deprecated that my list From 2-Step to Zolo - RYM's Genre Lists in extenso Directory didn't include a list for hypnagogic pop. Well, back then I was only familiar with TheScientist's excellent (but for other reasons excluded) RYM Ultimate Box Set > Hypnagogic Pop, which is still very much the standard RYM list for this genre & serves esp. as a beginner's guide. Over time some more formidable, hybrid, & genrecrossing lists like Neo-psychedelic low-fi hypnagogic indie noisefolk garbage or Hauntology / Glo-fi / Hypnagogic / Eldritchtronica were published, but I still found an extensive exploration of this subgenre lacking.

This seems odd as the genre is rather popular on this site & quite a number of insiders can be identified. Yet, when observing how hypnagogic pop is intermingled with a dozen other genres in a constant flow it becomes clear that in any reasonable reality these genres cannot be neatly separated from one another - many artists & albums that appear here could just as well be on a list about vaporwave, chillwave, neo-psychedelia, lo-fi indie etc. list. These recent genres in combination create such a genre-defying mess that any attempt to bring order into the chaos is ensured to cause more mess.

Yet I did try with this list in an almost purist manner to focus on artists & releases that have hypnagogic pop as a primary genre. This also meant excluding many highly acclaimed artists, which are sometimes brought into correlation with HP, but only show sporadic elements of the genre (no Oneohtrix Point Never or Zola Jesus), and instead trying to dig deeper into the unknown & elicited a wide range of artists & releases which are completely overlooked on this site considering the number of ratings & list appearances.

If this list should fail in defining the genre by extensive outlining, then at least it shall be a nice trip through the dungeons of post-post-modern underground pop.

- For attempts to verbally define & distinguish the genre I recommend you go to above mentioned box set list.

- This list is structured into two parts: 1 artists (divided into household names & underdogs) 2. a chronology of releases with the order a) albums b) EPs c) singles in alphabetic order for each year.

Quotes

Hypnagogic pop artists have a tendency to: “turn trash, something shallow and determinedly throwaway, into something sacred or mystical” and to “manipulate their material to defamiliarise it and give it a sense of the uncanny”. (Adam Harper, Dummy magazine)

The genre has been likened to: “sonic fictions or intentional forgeries, creating half-baked memories of things that never were—approximating the imprecise nature of memory itself” (Stone Blue Editors)

It has been described as “tak(ing) aspects of modern culture and nostalgia and transform(ing) them into new collective memories”. (Luna Vega)

made public: 16.1.2019, 100 faves as of 2.6.19, 200 faves as of 17.1.2020, 400 as of 27.12.20

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2108.09 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2229 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment