A Sense of Doubt blog post #3106 - All-Star Superman - Comic Book Sunday for 2308.20

see the series and synopses here: https://comicvine.gamespot.com/all-star-superman/4050-18139/

ALL-STAR SUPERMAN

https://comicbookroundup.com/comic-books/reviews/dc-comics/all-star-superman

https://atomicjunkshop.com/comics-you-should-own-all-star-superman/

Comics You Should Own – ‘All Star Superman’

Hi, and welcome to Comics You Should Own, a semi-regular series about comics I think you should own. I began writing these a little over seventeen years ago, and I’m still doing it, because I dig writing long-form essays about comics. I republished my early posts, which I originally wrote on my personal blog, at Comics Should Be Good about ten years ago, but since their redesign, most of the images have been lost, so I figured it was about time I published these a third time, here on our new blog. I plan on keeping them exactly the same, which is why my references might be a bit out of date and, early on, I don’t write about art as much as I do now. But I hope you enjoy these, and if you’ve never read them before, I hope they give you something to read that you might have missed. I’m planning on doing these once a week until I have all the old ones here at the blog. Today: It’s time for another Grant Morrison masterpiece! This post was originally published on 24 January 2016. As always, you can click on the images to see them better. Enjoy!

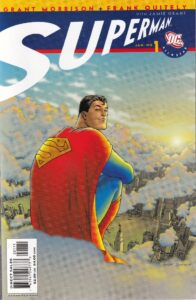

All-Star Superman by Grant “Solaris is so cool, you guys” Morrison (writer), Frank Quitely (penciller), Jamie Grant (inker/colorist), Phil Balsman (letterer, issues #1-8), and Travis Lanham (letterer, issues #9-12).

Published by DC, 12 issues (#1-12), cover dated January 2006 – October 2008.

Some SPOILERS below, but not too many!

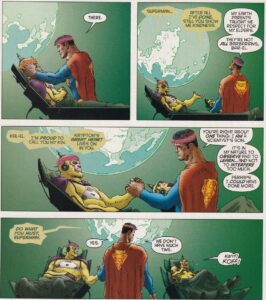

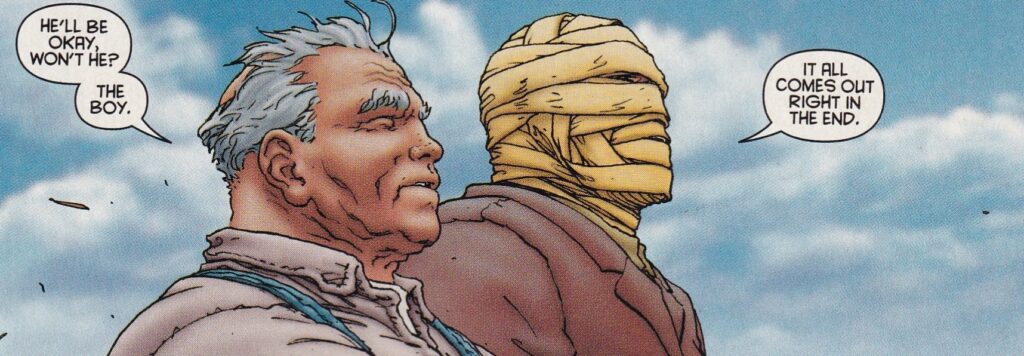

The mythological aspect of Superman is always fairly overt, as it’s such an easy metaphor, but Grant Morrison’s first crack at writing a solo Superman book brings it more to the fore than most Superman stories, not only with regard to the title character but in conjunction with many other characters, as well.  The very first scene in the book, after all, shows us Dr. Leo Quintum stealing fire from the heavens, and the Prometheus metaphor extends into the series as a whole, even as Quintum also fulfills a Joseph role, right down to his coat of many colors. Morrison mixes myths skillfully, bringing in the Greek templates, Biblical templates, Norse templates, and a Viking funeral at the end (where it mixes with Greek philosophy, not myth). Superman lends himself to myth, but Morrison understands that his entire world can, as well, simply by his living in it. Superman’s world isn’t “realistic” in many senses of the word, because Superman’s presence makes others strive for excellence. We see this in Quintum and Lex Luthor, two sides of a coin, as one tries to match Superman’s example by making the world a better place while the other can’t overcome his jealousy and uses his vast intellect to bring Superman down. Luthor is a tragic figure, of course, and while Morrison doesn’t turn him sympathetic, he’s still sad to consider, especially in the climax of the book, when Superman uses words to bring him down rather than his fists.

The very first scene in the book, after all, shows us Dr. Leo Quintum stealing fire from the heavens, and the Prometheus metaphor extends into the series as a whole, even as Quintum also fulfills a Joseph role, right down to his coat of many colors. Morrison mixes myths skillfully, bringing in the Greek templates, Biblical templates, Norse templates, and a Viking funeral at the end (where it mixes with Greek philosophy, not myth). Superman lends himself to myth, but Morrison understands that his entire world can, as well, simply by his living in it. Superman’s world isn’t “realistic” in many senses of the word, because Superman’s presence makes others strive for excellence. We see this in Quintum and Lex Luthor, two sides of a coin, as one tries to match Superman’s example by making the world a better place while the other can’t overcome his jealousy and uses his vast intellect to bring Superman down. Luthor is a tragic figure, of course, and while Morrison doesn’t turn him sympathetic, he’s still sad to consider, especially in the climax of the book, when Superman uses words to bring him down rather than his fists.

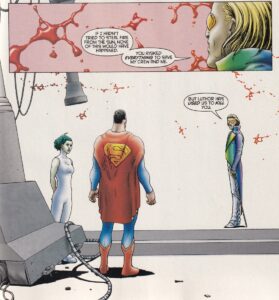

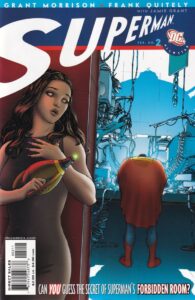

Superman is the most mythic of superheroes, but Morrison manages to keep him this way while humanizing him, which makes his struggles more relatable and tragic.  This balance is what drives the story, as Superman is given a death sentence in issue #1 when he saves Dr. Quintum from dying in the sun (thanks to one of Luthor’s creations) and receives too much solar radiation for his cells to process. It gives him new superpowers but also kills his cells, so the rest of the series is about him trying to wrap up his affairs before his death. The threat of mortality is often a good narrative choice, because it adds importance to the way a life is lived, and while Morrison can’t exactly kill off Superman (the “All Star” line isn’t “Elseworlds,” and it’s clear that Morrison is writing the “real” Superman far more than, say, Frank Miller did in All Star Batman), they come as close as they possibly can. Morrison makes us pay more attention to their main character because we know the specter of death is bearing down on him, so all his choices have an added poignancy. His revelation of his secret identity to Lois at the end of issue #1, for instance, should be a major life change for both of them, but Morrison subverts that expectation when Lois simply refuses to believe that Clark Kent could be Superman. It becomes a funny moment, but it’s still tragic underneath, because not only can Superman and Lois not be together as romantic partners, but she doesn’t even believe he’s telling her the truth … and, of course, he’s not completely honest with her, as she finds out from Quintum that he’s dying.

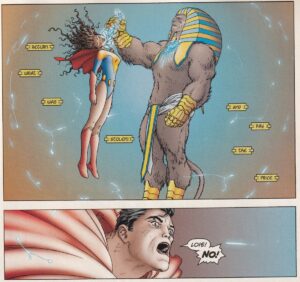

This balance is what drives the story, as Superman is given a death sentence in issue #1 when he saves Dr. Quintum from dying in the sun (thanks to one of Luthor’s creations) and receives too much solar radiation for his cells to process. It gives him new superpowers but also kills his cells, so the rest of the series is about him trying to wrap up his affairs before his death. The threat of mortality is often a good narrative choice, because it adds importance to the way a life is lived, and while Morrison can’t exactly kill off Superman (the “All Star” line isn’t “Elseworlds,” and it’s clear that Morrison is writing the “real” Superman far more than, say, Frank Miller did in All Star Batman), they come as close as they possibly can. Morrison makes us pay more attention to their main character because we know the specter of death is bearing down on him, so all his choices have an added poignancy. His revelation of his secret identity to Lois at the end of issue #1, for instance, should be a major life change for both of them, but Morrison subverts that expectation when Lois simply refuses to believe that Clark Kent could be Superman. It becomes a funny moment, but it’s still tragic underneath, because not only can Superman and Lois not be together as romantic partners, but she doesn’t even believe he’s telling her the truth … and, of course, he’s not completely honest with her, as she finds out from Quintum that he’s dying.  Superman’s impending death not only colors his relationship with Lois, it affects his entire life. He becomes obsessed with finding a way to enlarge Kandor. He travels through time to say goodbye to his father, which he didn’t get to do the first time around. He tries to rescue the citizens of Bizarro World (which he would always do, of course, but there’s some added desperation to his actions this time). He’s oddly naïve about the new Kryptonians who arrive on Earth even after they give him reasons to suspect them. Finally, he tries throughout the comic to get through to Lex, interviewing him as Clark Kent in issue #5 and battling him in issue #12 as Superman. Yes, Superman is always optimistic, but Morrison’s death sentence on him makes his pleas to Lex a bit more plaintive, as if he knows he won’t be heeded but for the first time, it’s cutting him to the core that he won’t be. By killing him, Morrison can examine what a truly motivated Superman might do – he trusts Lois, he takes some more risks than he might otherwise (his rescue of Jimmy in issue #4, while a standard rescue, seems unnecessarily risky given that he has no idea what effect the underverse might have on him, and indeed, Black Kryptonite is very bad for him), and he tries harder than ever to solve the world’s problems. The bittersweet aspect of the book stems from that – he’s more powerful and more motivated than ever, but it can’t last.

Superman’s impending death not only colors his relationship with Lois, it affects his entire life. He becomes obsessed with finding a way to enlarge Kandor. He travels through time to say goodbye to his father, which he didn’t get to do the first time around. He tries to rescue the citizens of Bizarro World (which he would always do, of course, but there’s some added desperation to his actions this time). He’s oddly naïve about the new Kryptonians who arrive on Earth even after they give him reasons to suspect them. Finally, he tries throughout the comic to get through to Lex, interviewing him as Clark Kent in issue #5 and battling him in issue #12 as Superman. Yes, Superman is always optimistic, but Morrison’s death sentence on him makes his pleas to Lex a bit more plaintive, as if he knows he won’t be heeded but for the first time, it’s cutting him to the core that he won’t be. By killing him, Morrison can examine what a truly motivated Superman might do – he trusts Lois, he takes some more risks than he might otherwise (his rescue of Jimmy in issue #4, while a standard rescue, seems unnecessarily risky given that he has no idea what effect the underverse might have on him, and indeed, Black Kryptonite is very bad for him), and he tries harder than ever to solve the world’s problems. The bittersweet aspect of the book stems from that – he’s more powerful and more motivated than ever, but it can’t last.

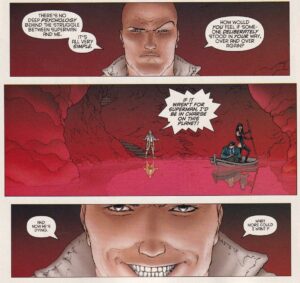

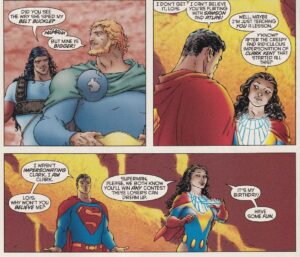

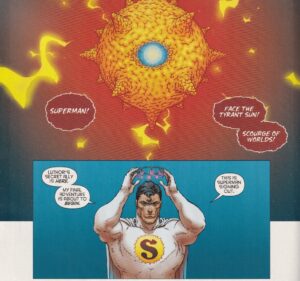

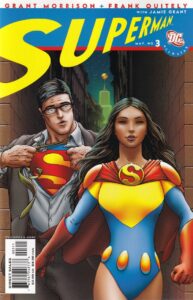

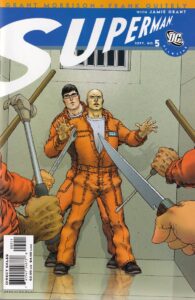

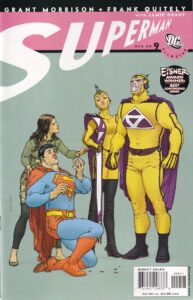

If we get back to the mythic element of the comic, it’s fascinating to consider the way Morrison extends the mythic beyond Superman.  Superman has always been the most Christ-like of superheroes, and Morrison dips into that a bit here, but the themes run throughout. As I noted, the Promethean myth is paramount on the first few pages, and it never really goes away. Both Quintum and Luthor can be seen as Prometheus, as they bring glory to the human race even though Lex does it with an ulterior motive. Quintum’s multi-colored jacket evokes the Biblical Joseph, and Quintum’s generosity and cleverness are Josephite qualities. Lex is more like Loki than Satan – he isn’t completely evil, and he enjoys sowing lethal mischief – and he’s able to find the “mistletoe” that kills Baldir/Superman. Lex’s problem is that he wants to be worshipped, but on his terms. Superman doesn’t want to be worshipped, and this seems unbelievable to Lex. Morrison digs into Roman myths a bit with the Sol Invictus cult, imagining a benevolent sun deity – Superman – battling a malevolent one – Solaris – in issue #11. Morrison gives us Hephaestus-Superman in issue #2, we get lesser demi-gods in Samson and Atlas, who appear in issue #3 (an issue in which Superman faces a riddling Sphinx, as well), and Clark Kent gets ferried by Nasthalthia (a distinctly Greek-sounding name, even though Morrison didn’t invent the character) across a hellishly red river to escape Lex’s prison riot in issue #4.

Superman has always been the most Christ-like of superheroes, and Morrison dips into that a bit here, but the themes run throughout. As I noted, the Promethean myth is paramount on the first few pages, and it never really goes away. Both Quintum and Luthor can be seen as Prometheus, as they bring glory to the human race even though Lex does it with an ulterior motive. Quintum’s multi-colored jacket evokes the Biblical Joseph, and Quintum’s generosity and cleverness are Josephite qualities. Lex is more like Loki than Satan – he isn’t completely evil, and he enjoys sowing lethal mischief – and he’s able to find the “mistletoe” that kills Baldir/Superman. Lex’s problem is that he wants to be worshipped, but on his terms. Superman doesn’t want to be worshipped, and this seems unbelievable to Lex. Morrison digs into Roman myths a bit with the Sol Invictus cult, imagining a benevolent sun deity – Superman – battling a malevolent one – Solaris – in issue #11. Morrison gives us Hephaestus-Superman in issue #2, we get lesser demi-gods in Samson and Atlas, who appear in issue #3 (an issue in which Superman faces a riddling Sphinx, as well), and Clark Kent gets ferried by Nasthalthia (a distinctly Greek-sounding name, even though Morrison didn’t invent the character) across a hellishly red river to escape Lex’s prison riot in issue #4.  All of these bits and pieces of myths build up a world in which Superman is, basically, a god – he performs plenty of miracles in this comic, after all – and presents him with labors to perform that prove his godliness. Morrison makes the connection between this comic and Heracles’s 12 Labors overt in issue #3, when Samson mentions that he completes 12 “super-challenges” before he dies (Samson also spoils the rest of the comic, but Superman’s feats of strength aren’t really the point). Myth is ever-present in Superman comics (and DC, in general, traffics in myth-making more than Marvel does), but Morrison has no interest in cloaking it in anything but what it is.

All of these bits and pieces of myths build up a world in which Superman is, basically, a god – he performs plenty of miracles in this comic, after all – and presents him with labors to perform that prove his godliness. Morrison makes the connection between this comic and Heracles’s 12 Labors overt in issue #3, when Samson mentions that he completes 12 “super-challenges” before he dies (Samson also spoils the rest of the comic, but Superman’s feats of strength aren’t really the point). Myth is ever-present in Superman comics (and DC, in general, traffics in myth-making more than Marvel does), but Morrison has no interest in cloaking it in anything but what it is.

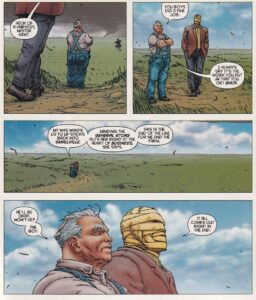

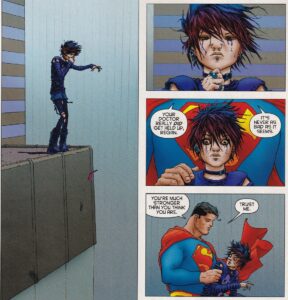

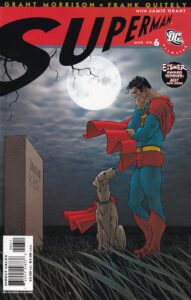

The best Morrison comics, however, don’t focus solely on the epic. Whenever Morrison gets too crazy without remembering that they’re writing about “real” people, their imagination tends to get away from them. The mythic aspects of All Star Superman are important and give the book its scope, but Morrison doesn’t forget the humanity of the characters, and this helps temper the epic parts of it so it’s far more relatable.  The most famous example in this series of Superman’s humanity is probably when he convinces the young girl to refrain from killing herself, but they’re all over the series. Issue #10 – in which Regan appears – is the most obvious, as Superman not only saves her life, but figures out what do with Kandor and even convinces the Kandorians to cure some tough diseases (he also creates life in that issue, but that’s not really humanizing, is it?). It’s not just in issue #10, however. In issue #3, Superman goes out of his way to rescue Krull when Samson throws him into orbit, and it’s not because he knows Krull was goaded into the attack by Samson, just that he doesn’t want to see Krull die. As Clark Kent, he saves Luthor’s life in issue #5 (Lex believes it’s dumb luck that Kent saves him, but of course it’s not). In issue #6, a young Superman fights the Chronovore and misses his father’s death, but present-day Superman goes back in time to have one final conversation with Jonathan Kent. He inspires Zibarro in issue #8. He saves Bar-El’s and Lilo’s lives in issue #9 even though they loathe what he represents. What makes this such a good Superman story is that Morrison finds the balance all Superman stories should have.

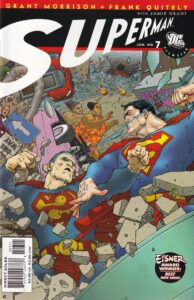

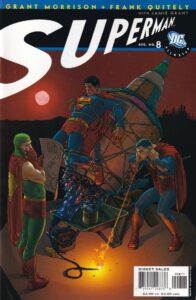

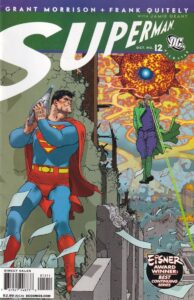

The most famous example in this series of Superman’s humanity is probably when he convinces the young girl to refrain from killing herself, but they’re all over the series. Issue #10 – in which Regan appears – is the most obvious, as Superman not only saves her life, but figures out what do with Kandor and even convinces the Kandorians to cure some tough diseases (he also creates life in that issue, but that’s not really humanizing, is it?). It’s not just in issue #10, however. In issue #3, Superman goes out of his way to rescue Krull when Samson throws him into orbit, and it’s not because he knows Krull was goaded into the attack by Samson, just that he doesn’t want to see Krull die. As Clark Kent, he saves Luthor’s life in issue #5 (Lex believes it’s dumb luck that Kent saves him, but of course it’s not). In issue #6, a young Superman fights the Chronovore and misses his father’s death, but present-day Superman goes back in time to have one final conversation with Jonathan Kent. He inspires Zibarro in issue #8. He saves Bar-El’s and Lilo’s lives in issue #9 even though they loathe what he represents. What makes this such a good Superman story is that Morrison finds the balance all Superman stories should have.  Some writers try for epic, but they end up coming up with a villain that can just punch hard, and Superman has to punch harder. Morrison certainly does that – Solaris is a good villain, and Lex Luthor with Superman’s powers is another one – but in most of the cases in this series, Superman is confronted with a problem that requires his brains as well as his brawn (and in some cases, only his brains and not his brawn). Morrison gives us a Superman who, if he’s not the smartest guy around, can think faster than anyone, so solutions present themselves more quickly. He can figure out variables much faster than others, so he can “see” the future better – as in issue #8, when he calculates exactly when Bizarro-Flash will reach his rocket ship. Morrison tends to write their superheroes as super-competent – their obsession with making Batman into a god-like being is proof of that – but with Superman, it’s just that his consciousness is so much more expansive than humans’ that he doesn’t have to be the smartest guy, because he just sees things completely differently than humans do. Lex actually comes to this realization in issue #12, but of course, it’s too late for him. The other things writers do is humanize Superman to the point where he feels less powerful and alien. Morrison never forgets that he’s not human, and they constantly remind us of that fact, but they find the right balance with the human side of him. They do this very well when Clark Kent is around, but it’s not the only time. Their Superman is “human,” too, and that makes the book richer.

Some writers try for epic, but they end up coming up with a villain that can just punch hard, and Superman has to punch harder. Morrison certainly does that – Solaris is a good villain, and Lex Luthor with Superman’s powers is another one – but in most of the cases in this series, Superman is confronted with a problem that requires his brains as well as his brawn (and in some cases, only his brains and not his brawn). Morrison gives us a Superman who, if he’s not the smartest guy around, can think faster than anyone, so solutions present themselves more quickly. He can figure out variables much faster than others, so he can “see” the future better – as in issue #8, when he calculates exactly when Bizarro-Flash will reach his rocket ship. Morrison tends to write their superheroes as super-competent – their obsession with making Batman into a god-like being is proof of that – but with Superman, it’s just that his consciousness is so much more expansive than humans’ that he doesn’t have to be the smartest guy, because he just sees things completely differently than humans do. Lex actually comes to this realization in issue #12, but of course, it’s too late for him. The other things writers do is humanize Superman to the point where he feels less powerful and alien. Morrison never forgets that he’s not human, and they constantly remind us of that fact, but they find the right balance with the human side of him. They do this very well when Clark Kent is around, but it’s not the only time. Their Superman is “human,” too, and that makes the book richer.

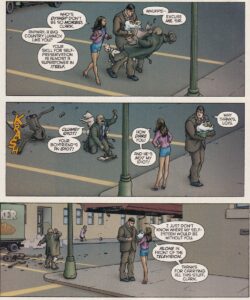

Morrison’s sense of humor is pretty strong in this comic, too, and in that sense, they’re ably aided by Frank Quitely, whose art on the book is wonderful.  Quitely’s precise line work and his quirky style makes everything look almost hyper-real, which makes him fairly ideal for comedy – it’s unusual that he hasn’t done more work that’s purely comedic. Morrison gives him instructions, but Quitely makes the humor work. This is especially true when Clark Kent is doing things that heighten his buffoonery but occasionally show him doing “Superman” things without giving away his secret identity. We first see this in issue #1, when Clark walks Lois home (and right before he reveals his secret identity to her) – Clark walks into a man crossing the street and knocks him down, but it’s only to stop him from getting crushed by a muffler that falls out of the overhead elevated train. I noted up above that Clark saves Lex’s life in issue #5 when he disconnects his electrical cord before it shorts out and catches fire, and he does it in as goofy a manner possible, which Quitely sells perfectly (Clark saves Lex’s life twice, in fact, but the other time, while he’s still pretending to be clumsy, isn’t quite as humorous). Quitely’s depiction of Clark/Superman is excellent, too – Clark slouches and is slightly pigeon-toed, and his ragged hair falls over his forehead, while Superman stands straight and has the classic spit-curl (one of Superman’s powers must be “super-styling,” because he can make his hair do that really quickly). It’s enough to make you believe that Clark and Superman are two different people, as Lois does even though Clark reveals that he’s Superman.

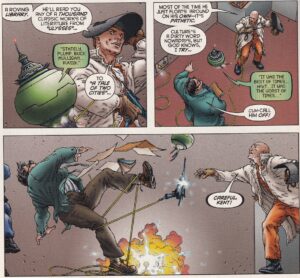

Quitely’s precise line work and his quirky style makes everything look almost hyper-real, which makes him fairly ideal for comedy – it’s unusual that he hasn’t done more work that’s purely comedic. Morrison gives him instructions, but Quitely makes the humor work. This is especially true when Clark Kent is doing things that heighten his buffoonery but occasionally show him doing “Superman” things without giving away his secret identity. We first see this in issue #1, when Clark walks Lois home (and right before he reveals his secret identity to her) – Clark walks into a man crossing the street and knocks him down, but it’s only to stop him from getting crushed by a muffler that falls out of the overhead elevated train. I noted up above that Clark saves Lex’s life in issue #5 when he disconnects his electrical cord before it shorts out and catches fire, and he does it in as goofy a manner possible, which Quitely sells perfectly (Clark saves Lex’s life twice, in fact, but the other time, while he’s still pretending to be clumsy, isn’t quite as humorous). Quitely’s depiction of Clark/Superman is excellent, too – Clark slouches and is slightly pigeon-toed, and his ragged hair falls over his forehead, while Superman stands straight and has the classic spit-curl (one of Superman’s powers must be “super-styling,” because he can make his hair do that really quickly). It’s enough to make you believe that Clark and Superman are two different people, as Lois does even though Clark reveals that he’s Superman.  Quitely’s thin-line, oddball style is perfect for the Jimmy Olsen-in-drag panel in issue #4, as Jimmy is just androgynous enough to make the drawing work without being offensive. There’s another wonderful comedic moment in issue #9, when Steve Lombard – who is just as big as Clark but looks more macho simply because of the way Quitely draws his and Clark’s movements – tries to set Clark’s jacket on fire. Quitely does wonderfully with the scene, showing Clark, again, as a bit of a buffoon, but then he surreptitiously uses his power to set Lombard’s toupée on fire to get revenge, and Quitely’s drawing of balding Lombard instantly ages him, showing him diminished even compared to Clark. The final panel of the sequence is tremendous, too, as Clark looks worriedly over at Jimmy and Lois, who seem to think something strange has just happened but they can’t quite figure out what it is. It’s a superb scene due to the way Quitely shifts the way we view the two men in it. Quitely doesn’t have a fluid style, so his action scenes are much more discrete scenes than other artists, but his attention to detail makes them wondrous to behold. We only see the Chronovore in a few panels, but it’s terrifying partly because it’s so cleanly delineated. Superman’s battle with Solaris is also amazing because of the precise line work.

Quitely’s thin-line, oddball style is perfect for the Jimmy Olsen-in-drag panel in issue #4, as Jimmy is just androgynous enough to make the drawing work without being offensive. There’s another wonderful comedic moment in issue #9, when Steve Lombard – who is just as big as Clark but looks more macho simply because of the way Quitely draws his and Clark’s movements – tries to set Clark’s jacket on fire. Quitely does wonderfully with the scene, showing Clark, again, as a bit of a buffoon, but then he surreptitiously uses his power to set Lombard’s toupée on fire to get revenge, and Quitely’s drawing of balding Lombard instantly ages him, showing him diminished even compared to Clark. The final panel of the sequence is tremendous, too, as Clark looks worriedly over at Jimmy and Lois, who seem to think something strange has just happened but they can’t quite figure out what it is. It’s a superb scene due to the way Quitely shifts the way we view the two men in it. Quitely doesn’t have a fluid style, so his action scenes are much more discrete scenes than other artists, but his attention to detail makes them wondrous to behold. We only see the Chronovore in a few panels, but it’s terrifying partly because it’s so cleanly delineated. Superman’s battle with Solaris is also amazing because of the precise line work.  Quitely draws every piece of wreckage in the fights, so the damage hits harder, as we see everything that has been destroyed. Jamie Grant’s shiny digital coloring might not work with every artist or book, but with Quitely’s fine line and with Morrison’s “bright” script – despite some dark corners in the book, it’s a comic about how Superman saves everyone because he’s, well, super – it assists greatly. Grant’s sheen on Quintum’s Technicolor dream coat, the lava that Bar-El and Lilo frolic in, and on Solaris’s malevolent surface, for instance, makes them stand out wonderfully against the “flatter” colors of the main participants (none of the colors are traditionally “flat,” but Grant makes some of the more basic than others). This kind of digital coloring has become the standard in the decade since All Star Superman, and it doesn’t work on every book, but it works very well here.

Quitely draws every piece of wreckage in the fights, so the damage hits harder, as we see everything that has been destroyed. Jamie Grant’s shiny digital coloring might not work with every artist or book, but with Quitely’s fine line and with Morrison’s “bright” script – despite some dark corners in the book, it’s a comic about how Superman saves everyone because he’s, well, super – it assists greatly. Grant’s sheen on Quintum’s Technicolor dream coat, the lava that Bar-El and Lilo frolic in, and on Solaris’s malevolent surface, for instance, makes them stand out wonderfully against the “flatter” colors of the main participants (none of the colors are traditionally “flat,” but Grant makes some of the more basic than others). This kind of digital coloring has become the standard in the decade since All Star Superman, and it doesn’t work on every book, but it works very well here.

All Star Superman is a brilliant Superman story partly because Morrison doesn’t need to continue it. There’s a finality to it, which makes it work a bit better (I know that, if this were the “real” Superman, a new writer would figure out a way to undo Morrison’s ending, which wouldn’t lessen the impact of what Morrison does, but the fact that there’s no issue #13 helps make this feel more important).  More than that, though, is that Morrison is able to “sum up” Superman, which writers of a continuing serial can do, but then they can’t really go anywhere with it. Morrison is able to do a “greatest hits” version of Superman, one that distills everything great about the character into several short stories, without worrying about the long-term impact they will have. All Star Superman still relies a bit too much on our prior knowledge of the characters – Lois, for instance, is a decent character in the book, but there’s not much in the series that would make us really understand why she cares about Superman other than he’s dreamy – but not as much as some comics. Morrison’s penchant for “wow” moments occasionally overwhelms their ability to make the characters “real,” but their best comics find a way to balance those perfectly, and that’s what we get in All Star Superman. It’s probably not a Comic You Should Own, because it’s more likely a Comic You Already Own, but that doesn’t mean it’s not fun to revisit it. Re-read it today!

More than that, though, is that Morrison is able to “sum up” Superman, which writers of a continuing serial can do, but then they can’t really go anywhere with it. Morrison is able to do a “greatest hits” version of Superman, one that distills everything great about the character into several short stories, without worrying about the long-term impact they will have. All Star Superman still relies a bit too much on our prior knowledge of the characters – Lois, for instance, is a decent character in the book, but there’s not much in the series that would make us really understand why she cares about Superman other than he’s dreamy – but not as much as some comics. Morrison’s penchant for “wow” moments occasionally overwhelms their ability to make the characters “real,” but their best comics find a way to balance those perfectly, and that’s what we get in All Star Superman. It’s probably not a Comic You Should Own, because it’s more likely a Comic You Already Own, but that doesn’t mean it’s not fun to revisit it. Re-read it today!

As always, you can check out the archives! They’re almost complete!

[There’s an Absolute Edition of this, which I would love to get, but I linked to the Deluxe Edition, which is cheaper. Anyway, there’s not much else to say about this, is there? I changed Morrison’s pronouns in this, but if you happen to spot any I missed, please let me know. I would appreciate it!

I’m almost done reposting all my old essays – then I have to get to work on new stuff! I’m up to the challenge!]

Author: Greg Burgas

DC Showcase: ‘All-Star Superman’ Comic Review

There are good stories, there are great stories, and then… there are All-Star stories; there is All-Star Superman.

Ever since its conclusion in 2008, All-Star Superman–the seminal work by Grant Morrison, Frank Quitely, and Jamie Grant–has cemented its legendary reputation within the comic book world. It’s a tale that, somehow, managed to not just live up to its already larger-than-life protagonist, but managed to raise Superman to even greater heights, and earned two Harvey Awards and three Eisners in the process.

All-Star Superman is such a perfect, powerful interpretation of Superman that it is the core inspiration for James Gunn’s Superman: Legacy movie coming in 2025. It’s a comic that perfectly balances the fanciful, limitless boundaries of the comic book medium with the deepest, most personal elements of the human experience. A book unlike any other–a love letter to comics, a perfect encapsulation of the Superman mythos, and an optimistic prayer for the future of humanity.

And I used to hate it.

[Warning: Some spoilers discussed for All-Star Superman below!]

My first reactions to All-Star Superman

When I first experienced All-Star Superman, I did it all wrong. Not only was I totally unfamiliar with comic books as a medium, but I did the dreaded thing that will make any bookworm squirm: I watched the movie first.

I saw the animated movie adaptation and nothing could have prepared me. I spent far too much time trying to figure out exactly how everything fits into the bigger DC Universe, trying to cram the narrative and unique characterizations into my limited, pre-existing DC knowledge.

It was a sobering experience that confused me. I mean, (SPOILER ALERT) Superman died. There was no Justice League, no Batman, just a bunch of random names and a barely-cohesive plot. It wasn’t an awful experience, but it was enough that when I returned to All-Star in its original medium… it still didn’t click.

It was–wacky! I would quickly learn that Grant Morrison had a knack for that: wild, high-concept stories that felt too poorly put together and rushed to make cohesive sense. As a beginner, most stories I’d found were fairly easy to follow, but Morrison just seemed to throw things at the audience to see what sticks. As someone who thought comics were all about continuity and power scales (I had been on the internet), I was confuddled.

I also outright hated the art style of Frank Quitely. Jamie Grant’s lively colors felt wasted on linework that was so rough and stylized. In my opinion, most popular comics from the ’00s had an aggressively off-putting, grimy sense of realism, but at least that felt “mature” in my young adult mind. I assumed that was the proper way comics should be drawn. After all, isn’t “realistic” the aim?

Yes, I was what is now clinically referred to as a “goober”.

But what made me turn around and re-evaluate my own views was actually Jay Babcock’s foreword to another Grant Morrison book: Final Crisis. At the time, I was struggling with Final Crisis in the same way that I’d been with All-Star Superman. I knew I was missing something. I knew I had to solve the puzzle! In that foreword, Jay Babcock handed me the missing piece.

He described reading a moment of pure cosmic absurdity in Final Crisis and just smiling and laughing. That was it. He goes on to revel in the imaginative, progressive, purely “WEIRD and GREAT and TRUE” ideas that the comic just—embraced. And he embraced them too. They are elements that comic books can do so well. There are places and stories that comics can go that no other medium can, and they’re meant to be creative, wild, and—above all else—fun.

I had approached comics wrong. I had come from such a logical, rigid standpoint that I truly think I lost what it felt like to be a child playing with action figures in my backyard, imagining wild and crazy adventures. When I tried it again—with that mentality in my heart—I discovered something crazy.

I started to love All-Star Superman.

The story of All-Star Superman

All-Star Superman is an out-of-continuity “Elseworlds” story set during the final days of Superman. After Lex Luthor’s ultimate plan works, Superman’s cells overcharge with solar radiation and start decaying beyond control. The Man of Steel is dying, but there are things left he needs to do.

Although it’s the inciting incident and the ultimate climax of the story, All-Star Superman is not a story about Superman’s death. It is a celebration of his life and his boundless love—for Lois Lane, for his family and friends, but, above all, for his adopted home.

Each chapter goes in new, exciting directions, pulling some of the most inventive scenarios showcasing Superman’s “Final 12 Labors of Heroism”. It pits him against classic foes like Parasite and Bizarro, but also against original characters like Solaris the Tyrant Sun.

The story works both as a complete whole and as twelve individual stories, with each issue spinning a standalone story in compelling and utterly imaginative ways. It’s here that the creative team pulls off a few “heroic labors” of their own.

What this comic series reveals about Superman

There’s a dichotomy to Superman, hidden in plain sight, that many writers ignore. Writers tend to approach Superman in one of two ways: they either make him bigger than life (see Superman: Up in the Sky) or bring him down to earth (see The Warworld Saga). Now, these are both solid Superman stories, but writers tend to always lean one way, to either the “Super” or the “Man”.

In Superman Smashes the Klan, we get a very grounded Superman in a literal and metaphorical sense. A younger man, his main struggle revolves around both internal and external acceptance. As a result, one of his most defining powers, flight, has to be earned through his personal character growth.

Compare that to Superman: Unchained which highlights the raw, unyielding might of this god among men, and you have a very different story. Finding the harmony between “Super” or “Man” without sacrificing either is EXACTLY what All-Star Superman does so well.

Morrison powered up Superman more than ever before. From the very beginning, All-Star is a story where that can happen. Issue #1 sets the stakes: Superman is dying. Nothing will stop that, it’s only a matter of “when”. This allows for several storytelling advantages. If the stakes are not related to the power-scaling of our protagonist, if his powers will not save him, then they can be whatever they want to be without issue. When justifying power-scaling becomes obsolete, the focus can shift to more creative avenues like the heartfelt resonance of characters like Jimmy Olsen, Lois Lane, and even Clark Kent himself.

Every issue maintains this perfect balancing act. Take issue #6, for example. A multidimensional time-eater attacks Smallville! It’s here to devour everyone’s futures, and only Superman and his time-traveling descendants can stop it! A plot ripped RIGHT out of the silver age, just dripping with abstract sci-fi deliciousness — but it’s a distraction. The heart of the story is a boy, his dad, and the fact that no one escapes death. No beat feels out of place, no emotion or wonder is lost. It’s the perfect response to the age-old question:

“If Superman truly is the modern-day Atlas, then how can he be relatable?”

Simple. Remember that the modern-day Atlas grew up in Kansas.

The art of All-Star Superman

Frank Quitely’s linework is unusual compared to standard comic fare, and may be polarizing, but hear me out: The art is what makes this comic work.

Jamie Grant’s colors pop and shine in a way that, in the 2000s, would have seemed totally alien to most comics fans. Put together, Quitely and Grant’s art makes this comic feel almost anachronistic, like DC pulled it right out of the 50s when sci-fi artwork was all ray guns and fishbowl helmets. Grant really is the unsung hero of this story. He built its identity.

It should be hard to take characters that have existed for 75 years and make them unique, yet Quitely effortlessly made these characters his own. He purely excels at building character and framing action. A sign of a good artist is when they make the writer feel obsolete, and there is so much silent storytelling in this book that is easy to miss.

Every character Quitely builds is a masterclass in subtlety, from Lex Luthor purposefully being someone who always has to look up at Clark Kent, to the difference in stature between Clark and his alter-ego. There are so many emotional beats in this story that would not have worked if the art failed. When making a comic, writing is just words. Art brings those words to life. Quitely tells us exactly how to feel.

The best example I can give for this is in the first two pages of this book. There are only eight words on the first page and none on the second. It is the best opening to any comic I can remember. No introduction required.

Why All-Star Superman is a must-read

Some people hate Superman. They hate the idea of Superman, the enormity of Superman. Superman has always struggled to find a footing in a way that characters like Batman haven’t, and it’s because Superman is meant to be the physical embodiment of an ideal.

“Truth, Justice, and the American Way.”

But ideals are incomprehensibly massive. Intangible. Perhaps this is why Superman’s most iconic power is his ability to fly, to rise above it all.

To stay forever out of reach.

This makes Lex Luthor, in this book and forever, Superman’s perfect foil. Lex is how we look at Superman. It’s easy to feel unworthy of an ideal, to feel judged when we fall short, to have Superman looking “down” at us. No one wants to admit they’ve fallen short, and that can foster resentment. Resentment is selfish. It’s the inability to see past ourselves and grow by admitting our mistakes.

Lex Luthor is the epitome of selfishness. In one of the most quotable lines in all of All-Star Superman, Lex receives a taste of Superman’s power and, when it runs out due to his own selfish negligence, he proclaims that Superman is the reason he failed to save the world.

Superman responds, “You could have saved the world years ago had it truly mattered to you.” This is what Superman represents for this entire story, and what he’s represented since his creation.

Even on a balanced, physical playing field, the Man of Steel triumphs. Not by any feat of strength, but by a feat of character. Where Luthor has always been a caricature of man’s selfish ambition masquerading behind the guise of capitalistic altruism, Superman has always risen above. Flight is not just Superman’s most enviable power. It’s an analogy for the ideology Superman represents as something not unreachable, but aspirational.

If you have ever thought that Superman was boring, then I cannot implore you enough.

Read this book.

Final thoughts on All-Star Superman

“You will give the people of Earth an ideal to strive towards,” Jor-El says in the 2013 film Man of Steel. The speech was adapted from this very comic, where he would continue, “They will race, and stumble, and fall and crawl…and curse…and finally…they will join you in the sun.”

To me, this line is the truest thesis for Superman. It’s why the character endures, and why All-Star is so important. It’s the line that continues to give me hope for his future, in any medium.

Superman is both super and man: a literary metaphor for all that humanity could ever aspire to. It’s the reason I love Superman. Not because his powers are cool, or because his heart is like mine…

We should care about Superman because Superman cares about us.

One of the most important, yet easily dismissed, core tenets of Superman is that he is our hope. Our optimism. Our strength of resolve and compassion. Throughout All-Star Superman, the most emotional beats come when we, the reader, see that this man is dying, but time again his thoughts are with humanity first and himself second. The idea of Superman is the complete rejection that absolute power corrupts absolutely.

All-Star Superman is and will forever remain a seminal work in the long and storied history of Superman. With this as a basis, Superman: Legacy has the potential to embrace not just the heart of Superman, but the innate beauty and child-like wonder of comic books. This brings me hope. I want to see a Superman on the screen who is unafraid to be what he is, and I truly believe audiences will fall in love with this character all over again.

We’ll believe we can fly.

Have you read All-Star Superman before? Are you excited about Superman: Legacy? Let us know on Twitter @MyCosmicCircus and be sure to follow the site for more DC comics reviews coming soon!

Check out our full list of DC Showcases here, including our review of Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow!

All-Star Superman

Writer: Grant Morrison

Penciler: Frank Quitely

Inker and colorist: Jamie Grant

Letterers: Phil Balsman and Travis Lanham

Superman could be a tough sell. Despite being the first superhero to codify the genre in 1938, and arguably still the most iconic, it’s often difficult for those who only know him from cultural osmosis to understand his appeal. He can seem hokey, or “too powerful” to be interesting. I know these misconceptions because I held them until my early 20s, when I finally started reading Superman comics. Now, when people tell me they don’t like Superman, I show them this page.

This page, from All-Star Superman #10, is my single favorite page of comics. It also illustrates why All-Star Superman, as a complete 12-issue series published between 2005 and 2008, is the perfect comic for these trying times.

Describing All-Star Superman as a “feel-good” comic book story might seem to clash with its surface premise. When the Man of Steel is exposed to an overwhelming amount of solar energy, he learns that he only has a short time left to live. The thing is, he’s Superman, so of course he copes with impending doom as the greatest aspirational figure in fiction would: doing as much good for the world as superhumanly possible.

That mission manifests in many different ways. One of the first things he does is reveal his secret identity to Lois Lane, sharing a magical day with the love of his life as she’s temporarily gifted with superpowers (Lois and Clark had already been canonically married for over a decade at the time of publication, but All-Star exists within its own separate continuity). He visits Bizarro’s home planet and helps a Bizarro-Bizarro named “Zibarro.” And throughout it all, Superman is shown helping ordinary people at every opportunity.

Superman’s essential decency is displayed most profoundly in the tenth issue, titled “Neverending.” It’s peppered with small (for Superman) moments of kindness, like visiting sick children at a hospital, even as his condition worsens and Lex Luthor’s evil plans come closer to fruition.

There’s a moment in this sequence that would seem out of place during a first read. As Superman waves goodbye to a train he just saved, a distressed woman with a cell phone to her ear says “I got held up…! No… no, don’t put the phone down Regan! Just stay in the apartment! You have to believe me! I’m on my way!”

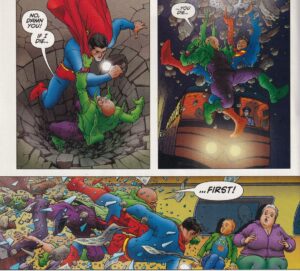

Five pages later, readers realize who the woman was on the phone with. A teenage girl at the ledge of a tall building tearfully drops her phone and watches it fall. She clasps her hands and closes her eyes in resignation. Clearly, she’s about to commit suicide by throwing herself down. Yet Superman appears from behind and puts a hand on her shoulder.

“Your doctor really did get held up, Regan,” he says. Her eyes widen. “It’s never as bad as it seems.”

She turns toward him. “You’re so much stronger than you think you are,” he says. “Trust me.” She embraces him.

We never see her again. Regan was a stranger to readers, and Superman. Superman could have gone anywhere in the world and done anything he wanted. Yet he chose to stop everything he was doing to save a single life. He did even more than save her. Even as he was dying, even as countless other important things were going in the world he took a moment to give her comfort.

Like I said, it’s my favorite page in the entire medium of comics, and being immaculately crafted isn’t the only reason I think about it constantly. For one, I believe it’s one of the finest demonstrations of Superman’s Jewish roots imbued by creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. To the best of my knowledge, no members of the All-Star creative team are Jewish, but intentionally or not, they built a pitch-perfect example of pikuach nefesh, the Jewish principle that “saving a life” is the greatest thing a person can do. I’m not particularly observant, but I am Jewish, and the idea that the opportunity to save even one life overrides all other obligations means a great deal to me, especially as a superhero fan.

But more urgently, I connect with this page because suicidal ideation is an all-too-real struggle for me. I’ve never attempted suicide, but I have been diagnosed with depression and anxiety, and was once hospitalized when my suicidal thoughts became too intense.

I do my best to cope. Medications help stabilize me and I have a great therapist. Some days are better than others, but on a regular basis I try to remember the mantra: “it’s never as bad as it seems. You’re so much stronger than you think you are. Trust me.”

I’ve had a lot of bad days recently. I know I’m not the only one feeling that way right now. And I know a Superman comic isn’t going to solve everything. But silly as it may seem, the idea that Superman would tell me I’m stronger than I think has kept me from the brink of despair.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Days ago = 2970 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment