A Sense of Doubt blog post #3174 - Marvel's Tomb of Dracula

As Halloween draws closer, it's time for a post on one of my all-time favorite comic book series: THE TOMB OF DRACULA from the 1970s by Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan.

The story works so well because it is a 70-issue storyline. The greater arc takes a while to get going, but the story creates an interconnected arc in one of the first example of episodic fiction in novel format with less emphasis on the single-issue round stories that stand-alone and longer plots and subplots of long form stories.

Marvel's Tomb of Dracula - WIKI

MARVEL LINK TO SERIES

TOMB OF DRACULA fan site

https://comicvine.gamespot.com/tomb-of-dracula/4050-2582/

Tomb of Dracula » 70 issues

VOLUME » Published by Marvel. Started in 1972.

Volume 1.

The much acclaimed saga of Marvel's Dracula and the Dracula Hunters. Written by Marv Wolfman and every issue drawn by legendary artist Gene Colan. The series lasted for 70 issues after which it ended with the seeming death of Dracula. However, the series was revived/replaced with the The Tomb of Dracula Magazine, which lasted for 6 issues. After that, Dracula appeared in the pages of Thor Issue #332 and #333, and most significantly in Doctor Strange Issue #59, 60, 61and 62 where he seemingly was killed. The Dracula saga was later continued in the 1991 mini-series Tomb of Dracula (vol.2), written and drawn by the same creative team as this volume.

Collected Editions

- Marvel Masterworks: The Tomb of Dracula Volume 1 (#1-11)

- Tomb of Dracula Volume 1 (#1-12)

- The Tomb of Dracula: The Complete Collection Volume 1 (#1-15)

- Decades: Marvel In The '70s - Legion of Monsters (#1)

- Blade: Undead By Daylight (#10, 24 & 58)

- Marvel Horror Lives Again! Omnibus (#10 & 67)

- Tomb of Dracula Volume 2 (#13-23)

- The Tomb of Dracula: The Complete Collection Volume 2 (#16-24)

- Werewolf By Night Omnibus (#18)

- Werewolf By Night: The Complete Collection Volume 1 (#18)

- Werewolf by Night: In the Blood (#18)

- Avengers/Doctor Strange: Rise of the Darkhold (#18-19)

- Tomb of Dracula Volume 3 (#24-31)

- The Tomb of Dracula: The Complete Collection Volume 3 (#25-35)

- The Tomb of Dracula: The Complete Collection Volume 4 (#36-54)

- Doctor Strange Epic Collection: Alone Against Eternity (#44)

Issue #18 has been translated into Spanish.

Issue #24 was reprinted as True Believers: The Criminally Insane: Dracula

It’s almost hard to imagine, looking at today’s comic book industry, but there was a time when horror comics were a major money-spinner for the “big two” comic book companies. The Tomb of Dracula stands out as the longest running and most successful of Marvel’s horror titles from the seventies, but there were a whole line of books being published featuring monsters old and new. It’s great that Marvel have taken the time and care to publish the complete series in three deluxe hardcover volumes. The Tomb of Dracula is a gem in Marvel’s seventies publishing crown, a delightfully enjoyable pulpy horror series that feels palpably more mature than a lot that the company was publishing at the same time.

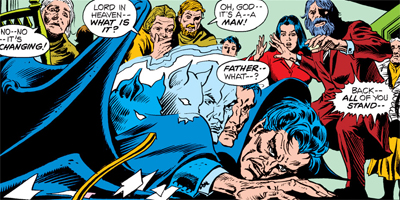

Of course, a large part of the success of Tomb of Dracula is down to the talent involved. When Marv Wolfman would serve as the writer from most of the comic’s run, he didn’t join the series until the seventh issue. On the other hand, artist Gene Colan had been working on the series since its inception, modelling the lead character on Jack Palance. In a rather wonderful illustration of just how in touch Colan was with the zeitgeist, Palance would play Dracula in a 1974 television movie Bram Stoker’s Dracula. (Indeed, Colan had actively lobbied for the book, with a portfolio featuring Palance as Dracula long before the television movie had been developed.)

Colan had a long career with Marvel, working on books like Iron Man or Daredevil. I have an immense fondness for his work on those classic superhero comics, but I think the artist did some of his very best work on Tomb of Dracula. The heavy, gothic atmosphere complimented his pencils perfectly, and the artist’s wonderful panel layouts made it a joy to follow the supernatural action across the page. Colan had a rare gift for illustrating both human characters and more supernatural elements, and his pages always had this almost ethereal feeling.

While he did some wonderful work with Marvel’s iconic heroes, the suits and masks frequently prevented Colan from rendering their expressive faces. One of the recurring joys of Tomb of Dracula is watching Dracula’s reactions when confronted with something that offends him, or seeing the anger and pride wash over his as he is challenged. Despite being fairly close to an archetypal presentation of the monster, right down to the cape, Colan’s Dracula has tremendous presence on the page, a dynamic and eye-catching manner.

Indeed, in the handful of crossover issues collected in the volume, you can see just how much Colan brings to the character. While the other artists present hardly do a bad job, there’s a certain something almost missing from their renditions of the Prince of Darkness. Colan’s Dracula is distinctly his own. I suspect part of the reason that Marvel was never able to make Dracula work quite as well again is down to the fact that Gene Colan was meant to draw Dracula. This collection looks absolutely beautiful.

If Gene Colan were meant to draw Dracula, then Marv Wolfman is perfectly suited to write him. Tomb of Dracula got off to a bit of a rocky start, and had a great deal of trouble finding a writer who could match Colan’s talents. Archie Goodwin and Gardner Fox were amongst those to try their hand at writing the book, to mixed success. Those early issues are a bit difficult to get a read on, as the series struggles to find its feet. It seems to bounce around, never quite sure of what it is or what it wants to be.

In particular, for example, there’s a decidedly “Gardner Fox” feeling to the issues penned by that author. It feels decidedly like a Silver Age comic book, recalling the author’s work on DC’s sixties comics – it features a rather surreal time-travel detour and a weird emphasis on genetic mutation to explain an other wise gothic monster to us. We’re told the creature suffers from “Richitis”, making it perhaps the strangest manifestation of Rickets I’ve ever seen. In another Fox-esque touch, the author explains the concept of an oubliette to his readers. It recalls the pseudo-scientific explanations that the writer was fond of.

It’s not that there’s anything inherently wrong with this approach, just that it doesn’t quite match the modern gothic set-up that Archie Goodwin established, and is miles away from the gothic melodrama that Marv Wolfman would invent. Wolfman’s arrival on the title was a welcome breath of fresh air, even just over half-a-year into the life of Marvel’s horror title. Wolfman’s stories seemed to synch up almost perfectly with Colan’s art, and the pair seemed to work almost in tandem for the rest of the comic’s fairly lengthy run.

Wolfman would emerge as one of the most high-profile comic book talents of the eighties, working on the New Teen Titans at DC comics with George Perez. The duo would even end up tasked with relaunching the DC universe in Crisis on Infinite Earths. At the time, Wolfman was seen as DC’s counterpart to Chris Claremont, and you can certainly see evidence of a similarity in approach here. In fact, Claremont steps in to write some of the Giant-Size Dracula issues collected here, as if to illustrate just how similar Wolfman and Claremont are in style.

Readers of Claremont’s Uncanny X-Men will recognise a lot of familiar storytelling methods and devices here. Wolfman shares Claremont’s passion for purple prose. When he asks where the “projector” is, Dracula is informed that it is “where the wind-chilled air swirls silently, undisturbed under the moonless sky… beneath the frostbitten blanket of snow unstirred by human presence…” That’s perhaps the least efficient answer ever.

However, such a deliciously melodramatic tone works surprisingly well for a horror comic based around the world’s most definitive and iconic vampire. It gives everything a heightened sense of scale and importance to everything happened, as if the fate of the very world hangs in the balance. It also creates a sense of poetry, as if we are watching just the latest iteration of some potentially timeless epic. It fits perfectly.

Another storytelling technique that Wolfman shares with Claremont is a knack for long-term plotting. From the moment he arrives on the title, it’s very clear that Wolfman has a long-term plan. It immediately steadies the title that has suffered from a lack of consistency. Throughout the run, Wolfman seems remarkably in control of the story he’s telling, where every detail seems placed there for a particular purpose, and each beat carefully and meticulously planned.

He has a wonderful knack for assuring the reader that the plot point will be handled in the future. We need only be patient. That takes a wonderful confidence, and it’s remarkable how skilled Wolfman’s follow-through is. For example, during an incident with Harker and Blade, we’re assured, “There is a moment of silence as the stake plunges down — but we shall not see its impact — that is for the next issue…” At one point, we see a poster for a play, and the narration promises, “We’ll learn more of that particular Dracula another time.”(I choose to believe that the play goes on tour and ends up in Boston for a brief appearance in the next volume.)

Indeed, this sort of long-term planning and plotting allows Wolfman to pull quite a few surprises out of his hat, and for the audience to accept that they were likely planned all along – like every other element of this tapestry. Clifton Graves, for example, betrays hid former master Dracula after appearing to die in an earlier issue. “You did mourn for me, didn’t you, Dracula?” he demands. “Or did you just give that madman’s laugh of yours and then forget I ever existed?” Wolfman’s story rewards those with long-term memories.

It takes a great deal of skill and self-control for an author to plot like that. Some reviewers would suggest that Claremont’s skill for that style of storytelling deteriorated as his run went on. I think that Wolfman deserves a great deal of credit for carefully managing and structuring all the different elements that surface over the course of The Tomb of Dracula. It’s seventy-issue run is remarkably well-put-together, seeming like a distant fore-father of those modern comics with defined long runs, books like Y: The Last Man and Sandman.

That’s not to suggest that Tomb of Dracula is quite up there with those classic comic book runs. After all, there are more than a few moments that strain the suspension of disbelief, even in a comic featuring the iconic cape-wearing proto-vampire. It seems like Scotland Yard accept the existence of the undead rather readily in these early issues, especially when some of the characters in the later stories go through a much stronger form of denial.

The dialogue and writing also feels a little dated. “Dig it,” Clifton states in the opening chapter, “a direct link with the original Count Dracula — and the castle built by the Count himself.” The dialogue occasionally dates the book more than the sideburns or fashion sense. Blade is perhaps the most obvious offender, speaking in a voice that is clearly meant to sound like the youth of the day. “Blade calls no one master — dig?” Although Wolfman does get some credit for acknowledging his influences. At one point, when Dracula confronts him, Blade states, “It ain’t John Shaft, red-eyes!”

Still, Blade is a fascinating character. I have a much softer spot for the revision that starred in his own trilogy of films, Wolfman and Colan manage to create this wonderfully energetic young character who almost bursts off the page whenever he appears. He feels like he has so much more life than anybody in the book except Dracula himself. He’s the next generation of young vampire hunter, and he even seems to advise the ageing Quincy Harker to step aside. “Then what, pops?” he demands at one point. “You’ve been dancing with the Count long enough.” Reading these first appearances from the character, I can understand how he came to headline his own series of movies, even before more recognisable characters like Spider-Man or Wolverine.

However, arguably the most fascinating part of Tomb of Dracula is Dracula himself. While the story features a collection of heroic vampire hunters to serve as foils for the Lord of the Vampire, the book works best as a character study of Bram Stoker’s iconic creation. It’s very hard to tell a serialised story centring on a villain. During the seventies, for example, DC struggled with a Joker on-going and a failed Secret Society of Super-Villains book. Perhaps the best villain-centred book in recent memory was Paul Cornell’s run on Action Comics, built around Lex Luthor.

It’s very hard to convince us to root for Dracula, particularly when the book doesn’t shy away from the brutality of his feeding habits. Wolfman uses a wonderful narrative technique of introducing us to each of Dracula’s young victims, so that we get a sense of exactly what he’s doing – these aren’t just nameless bodies piling up in the background. There’s also some rather blatant racism at play – not only his sense of superiority over humans, but his habit of referring to Blade as “a savage.”

There’s a none-too-subtle suggestion that Dracula himself is a misogynist. He seems to prefer feeding on women – an act that is rather implicitly sexual, especially given how Wolfman sets up many of the scenes. Many of Dracula’s victims are women walking home alone after failed dates, or worrying what their parents might think. Indeed, Dracula once even interrupts an attempted rape to feed. Even in a book supported by the Comic Code, sex is constantly present. However, Dracula’s aggression towards women is more deeply rooted than that – for example, he takes out his anger against Sheila out on other women, suggesting that they are all one and the same.

Wolfman and Colan deserve credit for refusing to water Dracula down. There are strange and surreal moments of compassion from the character, but they’re always contextualised, and firmly established as the exception rather than the rule. In Littlepool, his interactions with David, who wants to leave with him, betray a strange compassion. “The path I walk is too dangerous for one such as yourself,” he assures his colleague. In his own perverse way, he helps a dying wife gain revenge on her cheating, murdering husband.

That’s not to suggest Dracula is tempered in any way. He’s presented consistently as a murderer with no hesitation about taking human life. His ambitions are grand. Dracula does not merely wish to live in peace, he wants to rule the world. He is plotting for a time “when the Order of Vampires rules this world” – with Wolfman effectively casting Dracula as a super-villain building an “unseen army” to assist him in taking control of the planet. He justifies his decision in typical egomaniacal terms. “Mankind has changed little these past five-hundred years. Still they are selfish, arrogant — mindless. Indeed, they are a fertile crop one which awaits the sewing of the new order–” He makes it sound like he’d be doing mankind a favour by taking over.

It’s a very interesting avenue to take with Dracula, essentially presenting him as a super-villain in the style of Doctor Doom. Wolfman has a great deal of fun playing with certain standard comic book tropes using vampire story devices. At one point, for example, we get a deathtrap employing holy water. Dracula’s ambition, in the finest traditions of comic book super-villainy, doesn’t stop with the world itself. At one point he covets the chimera, with “power enough to conquer the far-flung galaxies themselves.”

In fact, Dracula’s deliciously arrogant voice is one of the pleasures of the volume. It’s delightful to hear the monster talking smack in the most grand terms possible, trying to maintain an air of sophistication while the rage seems to bubble beneath his skin. Confronted with Rachel’s crossbow, he counters, “How many times have I shown you, woman — this weapon is meaningless to one one who can become as the mist itself? But, since you seem too thick to learn, I’ll take it from you.” Trapping his foes, he boasts, “The time is almost nigh for the games to begin… games which shall surely lead to your deaths! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!”

He seems to enjoy that sort of large-scale villainy, and it’s to the credit of Wolfman as a writer that his character is never lost. Despite these grand plans and that wonderful rhetoric, Dracula remains a three-dimensional character. One of the shrewdest touches that Wolfman uses is to suggest that Dracula is effectively trying to conquer the world out of boredom. He suggests, time and again, that Dracula could find peace, but is too restless to do so.

In that respect, his thirst for blood is symbolic. Offered a bottomless pool of blood, he muses, “The blood would have merely quenched my thirst — it could never have satisfied my spirit. I require the constant hunt — the incessant searching for blood if only to keep my spirit alive.” This aspect of the character is mirrored late in the volume with the resurrected Bones, compelled to resolve some unfinished business to rest in peace. “Yet, it had reason to walk again — a quest — a challenge to its existence. It had to break free from the bonds of its chilling death.” Dracula must have something similar to keep him going after all this time, all this suffering, all this death. After the death of the Bones, we’re told that “Dracula understands the peacefulness of eternal rest — even if he can never touch it for himself.”

It speaks a lot to the skill of Colan and Wolfman that they are able to present Dracula as a tragic figure without shying away from his violence or brutality. Despite his unholy cravings, Dracula is seldom presented as a victim of anything but his own ego, and yet it’s hard not to pity the creature at times. Wolfman does an excellent job conveying the sense of a man out of time, flashing back and forth through the book to early lives and deaths of the Count.

There’s a sense that Dracula has entered a strange and changing world, one he’s not entirely able to process. When he pays for a woman’s drinks at the bar, she rightly identifies him as a bit of a relic. “There aren’t many blokes who’d pay a lady’s tab these days.” Later on, in Littlepool, he advises David, “You permit your woman to speak harshly, young man. Where I come from, such impertinence would not go unpunished.”Not that it excuses such views of course, but Dracula’s racism and misogyny are rooted in a different time.

Dracula’s adversaries have evolved as well. He’s hunted by Quincy Harker, the son of the lead from Bram Stoker’s original tale. He has now aged and is infirm, continuing the fight from the wheelchair and knowing his time must be approaching while Dracula lives on. His methods have evolved. We’re told, “He believes in gadgets… electronics… a scientific approach to vampire stalking.” It’s certainly an illustration of how far things have come, and just how old Dracula is.

Indeed, Wolfman seems to consciously pit Dracula against more modern monster archetypes, as if to emphasis the villain’s status as one of the most classic of monsters. He’s challenged by various modern archetypes, with the second volume even pitting him against a monster created by radiation. There’s a sense that Dracula is, to some extent, fighting to retain his title as the grandfather to modern monsters, trying to keep up with a world of horror that is rapidly evolving.

It’s telling that Doctor Sun is his main adversary in this volume. He is introduced as an oriental villain in the style of Fu Manchu, another pop culture archetype that was introduced after Dracula. Not too long after, but still a younger type of bad guy. However, as the series continues, we learn that Doctor Sun isn’t simply an homage to Fu Manchu. He’s a brain in a jar, calling to mind the high concept science-fiction of the thirties, forties and fifties. Indeed, Wolfman even introduces him in something of an homage to The Wizard of Oz, another fairytale from the middle of the last century. (“It’s a voice… coming from behind that curtain,” Rachel observes.)

Doctor Sun represents the new breed of monster that Dracula must compete against, the possible replacement for the traditional and old-school vampire. Doctor Sun even requires blood himself, making the comparison even more explicit. Confronting Dracula, Doctor Sun makes the argument himself, suggesting that he has arrived with a modern form of monster to bring an end to Dracula’s enduring reign. “I have been breeding your successor — the one who will rule all the undead… in the name of Doctor Sun.”

It isn’t only Dracula who is suffering in the changing times. Wolfman suggests that the world itself is going through a bit of a siesmic shift, with old superstitions and religious beliefs giving way to modern secularism. Father William in Littlepool finds himself confronted with a loss of religious faith. He counters by moving to the extreme, serving up a witch-hunt. It’s a scene that, sadly, feel familiar even today with many religious discussions dominated by extremists. Father Josiah Dawn laments, “Why, Lord — why is it each day the crowds diminish — the people leave earlier and earlier–? Why?”

Tomb of Dracula deals with surprisingly adult themes. There’s a constant undercurrent of sex and quite a bit of violence, but Wolfman also dares to wrestle a bit with religion and faith – certainly thorny subjects for a comic about an undead blood sucker. Although His presence would be developed further in the second half of the series, God is very much a character in Tomb of Dracula, albeit one who is relatively silent. Satan makes an appearance in the second omnibus collection, but God speaks through his messengers at his most articulate.

Wolfman makes it pretty explicit that Dracula is being punished by God for his blasphemy, “a man who the Lord himself has punished for his evil ways!” The monster is fond of identifying himself in explicitly religious terms. He boasts at one point, “Scowl and cringe — then bow before your master — for Dracula is a god unto himself! A god who holds the frail essence of your lives in his ever-powerful hands… and with one squeeze with his fingers, can crush that very life from your stinking mortal bones!”

Later on, fighting Gorna, he claims, “And know — that as the flames consume you — that Dracula is your god — and Dracula is indeed a vengeful god!” It’s an image that the book returns to time and again. Dracula is Lord of the Vampires, even in a religious sense. It’s clear that Dracula is positively angry at God for what has happened, and holds some very deep existential rage over everything that has befallen him. “Abandon that religious token, Eshcol,” he advises one potential victim in a pique of nihilistic rage. “Don’t you realise that your God is a fool. He’s a lunatic — who claims he created this world — of sin… of evil… of a thousand varied debaucheries. What sort of God can such a creator of madness be?”

And so it seems quite tragic how completely powerless Dracula is in the face of God, even indirectly. Despite his ability to raise the dead, and his massive strength and resources, it’s hard not to feel sorry for Dracula when he’s trapped inside a church. “Dracula cannot remain here — not in this dreadful place — this repulsive temple of a God he despises — there must be escape,” we’re told. And despite his wonderful abilities, Dracula is too weak to even escape. “Again and again, the Prince of Darkness lashes out as a man insane — or one wracked in hellborn agony — and twice more he falls back — broken — defeated — until, at last, he can contain the pain no longer — and slumps helplessly to the cold stone floor.”

Being in the presence of God causes Dracula supreme discomfort, as he acknowledges, “… The pain… I still feel it — even now as I leave this cursed temple — unending pain — clawing at me–“Despite the fact that God isn’t really an especially active protagonist in all this, he’s a very clear and very real danger to Dracula, and the one force that the Vampire Lord seems to genuinely fear. Wolfman would develop this theme in the second volume, but it’s established here.

Despite all of Dracula’s power, and the anger he has towards God, Wolfman makes it clear that Dracula is himself a pawn in a much larger game. Dracula’s games with Satan would come to a head in the next collection, but they’re foreshadowed here. “Yes, vampire — insanity born in hell… spawned by the very same master that you must serve,” Shiela’s father advises him. “All must serve some master — be it a god in heaven or in hell.”

And yet, despite the fact that we know God exists in Tomb of Dracula, it remains a harsh and uncaring universe, as the narration frequently reminds us. “More lives shall die this night,” we’re told at one point. “Some justly. Most unjustly. All futilely.” Even the dead will be denied a proper and fair memorial. “Stephen Willingham’s death will be attributed to causes unknown. No one will claim his body and within a month, he will be forgotten. Such is the sum total of 26 years of one man’s life.”

In a way, perhaps, this cold and indifferent universe might justify Dracula’s self-centred outlook. After all, he has been living in this world for centuries, so he knows what he must do to survive. To some of the characters inhabiting the world, he’s just one more expression of how sinister and how cynical this universe can be. Investigating the mysterious death of an accountant for his next of kin, Hannibal King demands of Dracula, “No — you’re not leaving yet. I want answers. What did the accountant learn? Why did he have to die?” Dracula mocks his attempt to find answers, “You must be joking, little man.” (To be fair, King does make an educated guess to tell the dead man’s wife.)

And yet, despite his coldness and brutality, Dracula remains a vaguely sympathetic figure – perhaps precisely because he doesn’t seek to be pitied. His brazen attitude and aggression are presented as if they mask some inner wound he’s too proud to show. If he realises the tragedy of his situation, he rarely dwells upon it, and Wolfman wisely avoids having Dracula appeal to the audience directly. Instead, Wolfman gives us a Dracula who tells his own biased story, but allows us to peer through the cracks in his cool veneer.

Even writing in his own private diary, Dracula can’t entirely give up the pretence, even if he must concede something. He refuses to try to justify himself, because he feels he needs no justification. “These notes must speak with no need of interpretation. They show at times my innate greatness, and also the still-human frailties that must course forever through my blood. For though I have been reborn like the phoenix many times, still there is the residue of my human beginnings.”

In his most private and intimate thoughts, he allows a brief hint of humanity to show through, a hint of the longing and isolation that have defined his extended life span. “Maria — still after 500 years I mourn for her, for though others called me the devil and the Impaler, she called me her love, as I did her.” This is really the closest Dracula allows himself to come to feeling sorry for himself, and it garners a great deal of sympathy because we see how much he has lost. His own daughter wants to kill him, for good reason. It’s hard not to feel a little sorry for a man in that situation.

Despite his own protestations, for example, it is quite clear that Dracula is capable of compassion – and maybe even love. There’s no denying the tenderness he seems to show Sheila Whittier, and his reluctance to corrupt her. (Making it somewhat tragic that he knows he must.) “It is almost sinful that you must be drawn into my web, girl,” he confesses. “Yet — as you sleep, I see an innocence within you that I lost so many centuries ago, if, indeed, I ever possessed it at all. You have an innocence my daughter could never hope to achieve.”

To be fair, Wolfman’s melodrama occasionally overwhelms him when it comes to writing Dracula as a pseudo-romantic lead. Dracula is a character who lends himself to this rather grand and over-the-top narrative voice, but it occasionally feels like Wolfman is egging the pudding just a little bit when the Vampire Lord ponders the possibility of a relationship with the damaged Sheila. “I am undead,” he states. “You are alive. There was never any hopes or futures for us.”

At the same time, Wolfman avoids taking the easy route in the portrayal of the relationship between Sheila and Dracula. He doesn’t present a completely healthy and loving romance between the pair – their interactions are dysfunctional at best and abusive at worst. In a way, it almost seems like a sharp deconstruction of the vampire love story, long before such stories entered the popular lexicon.

The narrator even explicitly picks apart any romantic ideal the reader may have. “Months before, Dracula’s first words to this frightened girl were: ‘I am not one of your tormentors.’ The Lord of Darkness lied.” Despite his reluctance to corrupt her, he’s possessive and abusive. When she decides to leave him, he abducts her, treating her as little more than an object. “I was merely protecting what is mine,”he states.

It’s fascinating that Wolfman and Colan made Dracula – a pop culture icon – such a compelling and well-rounded character in his own right. Despite the fact that Tomb of Dracula reads astoundingly well in this nice three-volume set, I’m almost disappointed that this version of Dracula hasn’t spun into the wider comics, or that Marvel hasn’t managed to keep this iteration of the character in publication. He’s a fascinating villain protagonist, and it’s remarkable how complex he is.

It’s also evident that Wolfman and Colan have a great fondness for the character and his various interpretations. In particular, I like the smaller touches that seem to reference the original story or famous iterations. When Dracula’s daughter, Lilith, comes visiting, she travels by air plane – a thoroughly modern method of transportation. However, she decides to snack on her journey, as if calling back to Dracula’s trip in the original novel.

Finding the Count in his coffin, we’re asked, “Dracula looks almost innocent as he sleeps, does he not, David?” It seems like an affectionate homage to the classic Bela Lugosi Dracula, where the killing of the monster as he sleeps seems almost tragic rather than necessary. There are countless little references hinted at and buried in Tomb of Dracula, and it’s clear that both writer and artist have a deep and abiding affection for the Count.

I also respect the decision to keep the Count relatively isolated from the rest of the Marvel Universe. It seems more of a side-effect of keeping Dracula based in Europe, but I like that he operates in his own corner. There is the odd reference to Marvel’s costumed heroes, with Hannibal King asked, “People can’t fly. Can they?” The detective thinks to himself, “I’ve heard there are a few who live in the States who can; in fact, they’re heroes who can do a lot more.” Appropriately enough, Chris Claremont’s Giant-Sized Dracula references “the mutie-haters.”

Other than that, though, it’s relatively low-key stuff – although the next volume does ramp-up the appearances from more established Marvel characters. There’s a nice crossover with Werewolf by Night included here, and I wouldn’t mind seeing that series get its own omnibus collection. Hopefully the recent Man-Thing collection allows Marvel the opportunity to get more of its classic monsters in print. Either way, it seems fitting that Dracula co-exists with Marvel’s werewolf character. After all, the Universal Horror movies were one of the first cinematic shared universes.

Tomb of Dracula is a fantastic collection, and it’s great to see the entire series collected in these three massive hardcover books. They’re an underrated gem, a highlight of Marvel’s seventies publishing, and it’s always fantastic to see some diversity in the books that they put out. It’s an absolute joy from start to finish.

Read our complete reviews of Marvel’s “Tomb of Dracula” collections:

- Tomb of Dracula Omnibus, Vol. I

- Tomb of Dracula Omnibus, Vol. II

- Tomb of Dracula Omnibus, Vol. III

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2310.28

- Days ago = 3039 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment