A Sense of Doubt blog post #2499 - JAMES BALDWIN debates William F Buckley and other Greatness

I feel it is fitting that this extended share is the 2499th post on my blog, penultimate to tomorrow's 2500th.

Reimagining The

James Baldwin And William F. Buckley Debate

September 20, 20204:44 PM ET

In February 1965, two of America's most towering public intellectuals

faced off at the University of Cambridge in England. They were there to debate

the proposition: "The American Dream is at the expense of the American

Negro."

Novelist

and essayist James Baldwin argued in favor. He did so by pointing to the

experience of the Black man in America. He said the legacy of slavery and white

supremacy had in effect "destroy[ed] his sense of reality." Black

fathers have no authority over their sons, Baldwin said, because a Black boy's

"father has no power in the world."

"There

is scarcely any hope for the American dream," Baldwin said, "because

the people who are denied participation in it, by their very presence, will

wreck it."

William F. Buckley, founder

of the conservative National Review, argued the opposing side.

Buckley acknowledged certain injustices of racism and discrimination, but said

Black people needed to do more to improve their own conditions.

"We

must also reach through to the Negro people and tell them that their best

chances are in a mobile society," Buckley said. "The most mobile

society in the world is the United States of America. And it is precisely that

mobility which will give opportunities to the Negroes which they must be

encouraged to take."

More than a half century later, their debate is being reargued, or "reimagined," on Sunday night by two modern accomplished thinkers: Harvard University professor Khalil Muhammad and David Frum, who writes for The Atlantic.

Their debate

— part of the March on Washington Film

Festival — is being held under the updated motion: "The

American Dream Is Still at the Expense of African Americans."

Baldwin and Buckley debated at a time when many Black Americans

were effectively being denied the right to vote. Just weeks after the debate,

civil rights marchers, including future congressman John Lewis, were bloodied

by Alabama state troopers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. It wasn't until

August of that year that President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act.

Some

55 years later, the ongoing struggle for equality has manifested itself in

nationwide protests against systemic racism and police violence against Black

Americans.

Frum, who was a speechwriter

for President George W. Bush, tells All

Things Considered that he wanted to participate to take stock of this moment

in history.

"I

think for a lot of us, this is a very heart-in-mouth moment, this fall of 2020.

And you can lose perspective that things have been worse," he says.

Muhammad,

who is a professor of history, race and public policy at Harvard's Kennedy

School, says he wanted the opportunity to "bring Baldwin's voice into

greater recognition."

After

a summer of protests over racial injustice while Black Americans die of the

coronavirus at disproportionate numbers, Muhammad says, "Baldwin's voice

as a novelist, as an essayist, as a critic of the hypocrisies of the nation and

its core contradictions, speaks to this moment in ways that few other writers

can."

Frum

argues that in the 55 years since Baldwin and Buckley spoke, "the story of

American politics has been the rise of Black political power, Black economic

power, Black legal power, Black power in culture." He acknowledges the

pessimism Baldwin felt in 1965, but says that now "when you tell people

that they are powerless, that America is against them, that they are not part

of the country, you don't teach action. You teach passivity."

Muhammad

counters that "the story of black people in America, while [Frum's] right,

is a story of great political vision and the dogged pursuit of making real the

promises of democracy, [Frum] gives far too much credit to the American system

as he explains it."

Muhammad

instead credits "people who actually challenged at every turn the status

quo. ... I completely reject the notion of despair as the natural outcome of

criticizing this country."

Both

Frum and Muhammad will speak and be cross-examined by students from the Howard

University Debate Team.

The

format of the event is a throwback to a time before the advent of social media.

While modern political debate often takes place online in short, frenetic

bursts, Muhammad thinks it's especially important for students of today to

witness a different approach in order to understand the fundamentals of

argument.

"In

our system of government, you can't 'cancel' someone at the bar of the Supreme

Court of justice," he says. "You have to make a case. And so I think

that this old, very old format of debate is still as useful today as it's

always been in order for people to hear precisely what the ideas are at

stake."

Frum

says debate is most effective when "people step away from it and they're

different than they were before, not only the audience, but the

participants."

When the Baldwin/Buckley

debate was over, the audience voted: Baldwin won, 544 to 164.

JAMES BALDWIN DEBATES WILLIAM F BUCKLEY

The Famous Baldwin-Buckley Debate Still Matters Today

In 1965, two American titans faced off on the subject of the country’s racial divides. Nearly 55 years later, the event has lost none of its relevance, as a recent book attests.

“The American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro,” James Baldwin declared on February 18, 1965, in his epochal debate with William F. Buckley Jr. at the University of Cambridge. Baldwin was echoing the motion of the debate—that the American dream was at the expense of black Americans, with Baldwin for, Buckley against—but his emphasis on the word is made his point clear. “I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing,” he said, his voice rising with the cadences of the pulpit. “For nothing.”

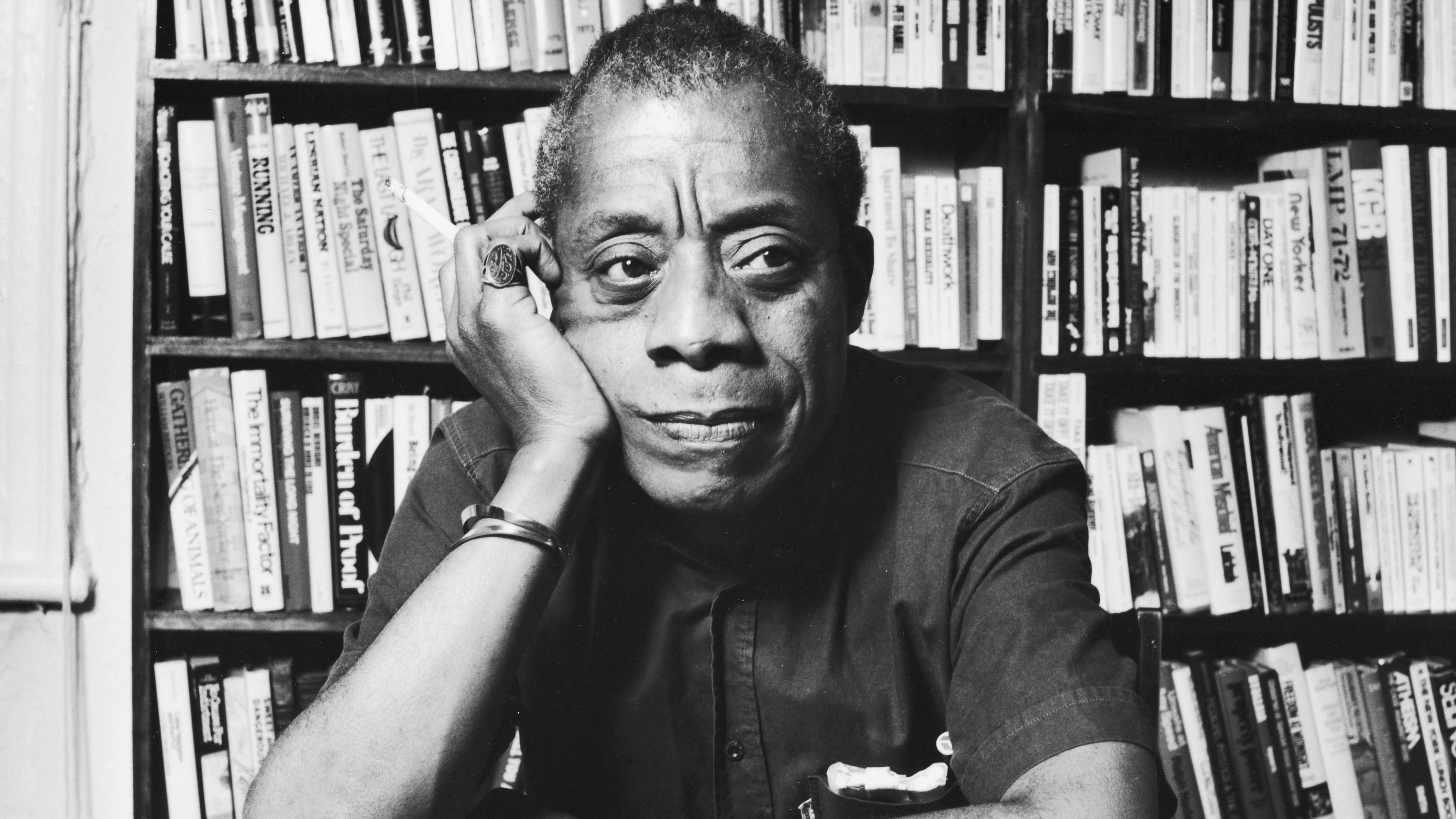

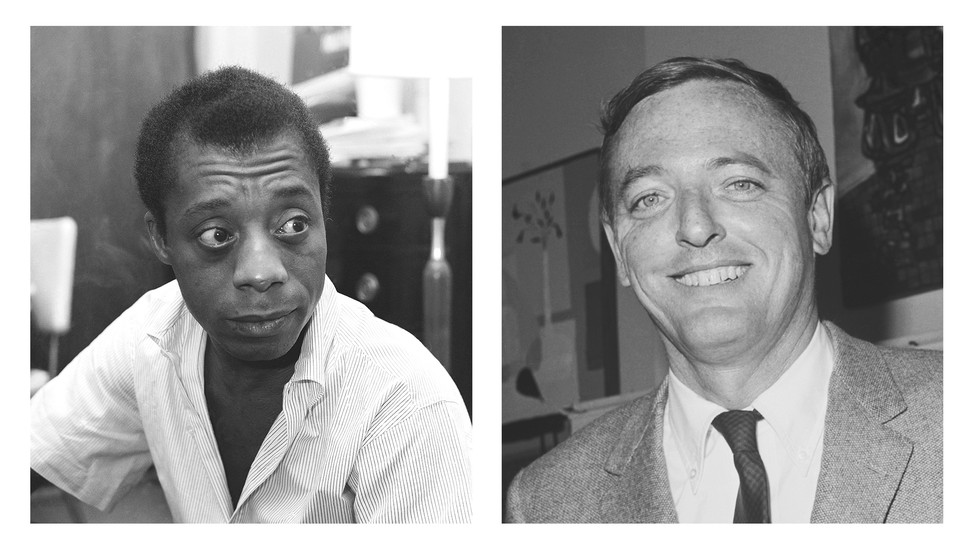

The packed auditorium was hushed. Here was a clash of diametrically opposed titans: In one corner was Baldwin, short, slender, almost androgynous with his still-youthful face, voice carrying the faintly cosmopolitan inflections he’d had for years. He was the debate’s radical, an esteemed writer unafraid to volcanically condemn white supremacy and the antiblack racism of conservative and liberal Americans alike. In the other corner was Buckley, tall, light-skinned, hair tightly combed and jaw stiff, his words chiseled with his signature transatlantic accent. If Baldwin—the verbal virtuoso who wrote moving portraits of black America and about life as a queer expatriate in Europe—stood for America’s need to change, Buckley positioned himself as the reasonable moderate who resisted the social transformations that civil-rights leaders called for, desegregation most of all. Some of the students in the audience knew him as nothing less than the father of modern American conservatism.

The famed debate, its riveting lead-up, and its aftermath are the subject of The Fire Is Upon Us, an exhaustive new study by Nicholas Buccola. In the first book to focus exclusively on this event, Buccola, who teaches political science at Linfield College, traces Baldwin’s and Buckley’s respective upbringings and political awakenings amid an America polarized by the issues of desegregation and racial equality. Understanding how each man came to his own conclusion, the book argues, can offer sharp insights into why Americans remain so at odds on the realities of racism today.

If not for the 1965 debate, Baldwin might never have met Buckley. In fact, Baldwin nearly had another opponent altogether. Before the Cambridge Union invited Buckley, it had reached out to staunchly segregationist politicians, all of whom declined. Buckley seemed an ideal alternative: an articulate, prominent sociopolitical critic who eschewed the racist epithets of conservatism’s more vocal white supremacists but who nonetheless supported segregation. As Buccola writes, Buckley saw the debate as a chance to defeat one of his ideological archnemeses on a public stage.

To Buckley’s irritation, though not entirely to his surprise, Baldwin delivered a rousing performance. “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, or 6, or 7,” Baldwin declared during the debate, “to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.” He argued that the evils of slavery had hardly been exorcised after abolition, but that rather, the country was essentially still the same for black Americans as it was during the days of legal slavery. After he spoke, he received a standing ovation.

It’s difficult to talk about either Baldwin or Buckley without referencing this contest; it has become a touchstone in both men’s lives, memorialized, for instance, in Raoul Peck’s landmark 2016 documentary on Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro. Although the ostensible focus of The Fire Is Upon Us is the Cambridge debate, more than half of it is devoted to explaining how Baldwin’s and Buckley’s upbringings informed their ideological beliefs and how they became rising stars in their respective worlds. Buccola doesn’t privilege Baldwin or Buckley, and chapters feature alternating sections devoted to each. Although some of the early segments and transitions feel rushed or awkward, the author paints a solid picture of each man once the book hits its stride.

The Fire Is Upon Us is written for readers on both the left and the right, its prose wonderfully accessible even for an audience that may be only superficially familiar with either Baldwin’s or Buckley’s work. Though he makes it clear by the end that his own ideological sympathies lie with Baldwin’s calls for racial justice, Buccola gives ample room to examining both men’s ideologies, without—and this is crucial—suggesting that Buckley’s racist views were somehow acceptable. (Perhaps because the bulk of the book focuses on the debate and its lead-up, Buccola delves less into the sometimes surprising ways in which Buckley’s public declarations on race shifted over the ensuing decades, with Buckley going so far as to suggest in 1970 that a black man should be elected president in the 1980s.)

Buccola’s study starts by examining the striking differences in how Baldwin and Buckley were raised. While Baldwin grew up poor in Harlem, Buckley was surrounded by privilege. His mother, Alöise Steiner Buckley, filled their home with servants and tutors for her 10 children. She was deeply Catholic, the seed of the rigid, Manichaean religious views that her son would adopt. Throughout his life, Buckley would become well known for the strict division of “good” and “evil” in his worldview, whereby Catholicism and capitalism were good, and atheism and socialism exemplified evil.

It was also clear to Alöise’s progeny what she thought about who should serve whom in American society. She was “a racist,” Buckley’s brother Reid recalled, because she “assumed that white people were intellectually superior to black people,” yet he added that “she truly loved black people and felt securely comfortable with them from the assumption of her superiority in intellect, character, and station.” This peculiar, patronizing dynamic presaged William’s own ideology, in that both mother and son believed in retaining barriers between black and white Americans as part of southern culture. As an adult, Buckley would often write that segregation was a temporary necessity, because black Americans were “not yet” advanced enough to be equal to whites, implying, with a condescension he perhaps thought uplifting, that they might one day be on the same level.

Still, Buckley considered himself different from the racist demagogues on the right. He viewed conservatives such as Strom Thurmond and Alabama’s pro–Jim Crow governor George Wallace as crass fringe elements, believing himself gentler and more sympathetic. Yet in reality, as Buccola points out, his views were simply a softer, more patrician version of white supremacy. Buckley believed that, as Buccola puts it, “a combination of noblesse oblige and constitutional principle might reform [the South] over time,” rather than immediate desegregation. “Buckley’s slogan,” Buccola wryly continues, “might be ‘Some Freedom … one day … when we decide you’re ready.’”

Buckley’s support of the South’s right to segregation and Baldwin’s condemnations of white America took place against the backdrop of a deeply divided America. Perhaps no statement better demonstrated that divide than what William Faulkner notoriously told Russell Warren Howe in 1956 when asked for his thoughts about “forcing” southern whites to accept integration. Though Faulkner claimed to eschew racial prejudice, he believed in the South keeping its way of life without government interference. “I don’t like forced integration any more than I like enforced segregation,” he answered. “If I have to choose between the United States government and Mississippi, then I’ll choose Mississippi … if it came to fighting I’d fight for Mississippi and against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes.” (Faulkner later claimed to have been misquoted, though there is no definitive evidence of this.) Faulkner would turn to violence to prevent integration, because segregation was—as Buckley would repeatedly say—a southern way of life.

Baldwin had flashed onto Buckley’s radar before. But with the 1962 publication of “Letter From a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin’s masterful indictment of white supremacy and reflection on the debilitating narrowness of his religious upbringing in The New Yorker, Buckley decided to pay special attention to this rising figure from Harlem. He was furious that Baldwin had attacked Christianity and white people all at once—and, worse, that he’d been given a major platform to do so. “James Baldwin is a disarming man,” began a piece by Garry Wills that Buckley commissioned for National Review, Buckley’s magazine, as a rebuke of Baldwin’s essay. Though Wills castigated Baldwin for blasphemy and for calling for “an immediate secession from [Western] civilization,” Wills had particular scorn for the literati who “failed” to be “angry” at Baldwin’s damning arguments. At the end of his essay, Wills acknowledged that Baldwin “is an adversary worthy of our best arguments.” Buckley, manifestly, felt the same.

As Buccola details, Baldwin, unlike Buckley, had suffered greatly before achieving fame as an author. He’d left New York in 1948, nearly penniless, for France, after deciding he could no longer survive the traumatizing racism of America—in northern and southern states alike. Though he found some respite in Paris, he still nearly committed suicide there after being arrested by the police on suspicion of having stolen a hotel’s bedsheet (which he had not). And he kept returning to America, both in his books and in his travels. He never hid away; instead, The Fire Is Upon Us argues, he put himself on the front lines of a civil-rights battle for nothing less than America’s soul.

Baldwin was proud of winning the Cambridge debate, but frustrated that Buckley, like so many other white Americans, had seemingly failed to understand what he was trying to say—almost like Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famous proposition in Philosophical Investigations that “if a lion could speak, we could not understand him,” for it would be speaking a language and of a reality alien to our own. They each had different “systems of reality,” Baldwin said during the debate; they were two lions of their field who were able to spar, but unable to comprehend each other.

Though a work of history, The Fire Is Upon Us holds a mirror up to the strident political and racial divisions of the U.S. in 2019. The language may be a little different today from what Baldwin and Buckley used, but the sharp terms of the debate over whether people of color in the United States get to have the American dream remains the same then as now. “The economic, educational, and health disparities across the color line,” Buccola writes at the end, “… happen because all of us allow them to happen, and until we summon the will to recognize this fact and do something about it, the American dream will remain a nightmare for many.” Buccola, like Baldwin, asks white Americans to acknowledge their complicity in the foundational inequalities that structure the country from bottom to top. Liberals and conservatives alike, the author argues, still have as much work to do today as they did in Baldwin’s day to reshape that nightmare into a dream worth striving for.

JAMES BALDWIN DISCUSSES RACISM ON THE DICK CAVETT SHOW

JAMES BALDWIN PIN DROP SPEECH

MALCOLM X DEBATES WITH JAMES BALDWIN

NOTES ON A NATIVE SON - THE WORLD ACCORDING TO JAMES BADLWIN

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2112.21 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2363 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment