A Sense of Doubt blog post #2497 - Annual Reading of "A Christmas Carol" and assorted Graphic Novels: WHAT I AM READING

Hold on to your hats! This one is a gale force wind of reading splendor.

Even when I am GRADING ROBOT going at full steam power, throttle all the way out, RPMs WAY TOO HIGH (what is that noise? Is that a thousand babies shrieking? No that's GRADING ROBOT's gears overworking...), I am still reading. I am listening to books on audio, I am reading before bed a night, and once a week, MAYBE, I am relaxing in an afternoon -- usually Sunday -- and reading more things during the daylight hours.

When I collapse in bed each night, I try to read a few single-issue comic books and then some of a novel. Even though I had started the collection of Alfred Bester stories I could never finish and my friend Sue's new novel, The Baseball Widow, I am on a graphic novel kick, and I have been working my way through all the graphic novels that have piled up, quite literally, in two huge stacks atop my dresser.

https://www.tcj.com/reviews/the-best-we-could-do/

THE BEST WE COULD DO

THE BEST WE COULD DO

The Best We Could Do opens with the complicated, grueling birth of artist Thi Bui’s child in New York City in 2005. Afterward, as Bui lies exhausted in her hospital bed, she realizes the impact of the event: “Family is now something I have created—and not just something I was born into. The responsibility is immense. A wave of empathy for my mother washes over me.”

Much of the subsequent narrative centers on the history of her mother, father, and siblings living in war-torn South Vietnam, then fleeing in 1978 when Bui was three. Though her family survived calamitous events, the emotional scars and cultural confusion they carry as collateral damage are considerable, resulting in gaps in communication and misunderstandings between each generation’s parents and their children. The weight of this history informs the entire narrative, at times foregrounded but always present.

In her early twenties, Bui traveled back to Vietnam to meet her extended family. It was shortly afterward that she began to record the family’s history, hoping that “if I bridged the gap between past and present… I could fill the void between my parents and me.” Her narrative flashes back and forth in time, illustrating how larger events (war, dictatorship, immigration) shaped the family’s lives. She records her father's traumatic, uprooted childhood in the 1950s (she calls him “Bố,” or “daddy”) and how he endured periods of living as a refugee with his abusive, philandering father in a country wracked with sociopolitical turmoil and poverty. Meanwhile, Bui's mother (“Má”) grew up in privilege as a child of a civil engineer, shielded for many years from the dire conditions of much of the country. After marrying Bố, Má gives birth to multiple children, usually under extremely difficult conditions, including her daughter, Bích, right before the Tet Offensive in 1968; a stillborn child, Thảo, in Saigon in 1974; and her son Tâm in a UN refugee camp in Malaysia in 1978.

The sections detailing the history of Vietnam and the war are powerful and painful, offering up a crash course in the history of that long and tragic conflict, from the dark seeds of its origin to its brutal aftermath under an oppressive dictatorship. In one section, Bui describes her parent’s happiness after getting married, living large on two incomes with the future seeming bright—while forces beyond their control are pointing toward large-scale death and destruction. “By this time,” Bui writes ominously, “the chess pieces of the war had been set. It was 1965.” Bui’s narrative voice is admirably straightforward, with an air of a reporter’s detachment, even when describing the most terrible events, infusing her family’s saga with power and grace.

Bui’s family were among the “boat people” who fled oppressive Communist rule after the war ended. But their troubles didn’t stop after arriving in America; along with the general culture shock, they must contend with bitter social and economic downsizing. Bui’s parents’ educational degrees are not recognized in this strange new land, resulting in long hours of minimum wage work and night schooling to better their economic prospects. Bui vividly describes these blighted early years, stuck at home with her father in an apartment in San Diego, while Má is at work and her sisters are at school. She and her little brother Tâm are left alone to cope with Bố's off-putting, distant demeanor, and his scary superstitions and paranoia. None of this made the family’s assimilation any easier.

With the issue of immigration currently hitting full boil stateside, the 2017 publication of The Best We Could Do couldn’t be more timely, or more welcome. Bui’s story movingly puts a human face to new arrivals to our country, illuminating the background of their lives and struggles. Contrary to the rhetoric of the most reactionary U.S. right-wing factions, immigrants are people, not statistics–more than the sum of their homelands, more than the color of their skin. Bui depicts, with unsparing candor, the multiple traumas associated with being forced out of one’s country into the unknown.

In her introduction, Bui describes the frustration she felt with her original plan of telling her family's story—a combination of text with some photographs and art: “I didn't feel like I had solved the storytelling problem of how to present history in a way that is human and relatable and not oversimplified. I thought turning it into a graphic novel might help.” She teams her brushy line with a burnt orange wash that lends an evocative, melancholic feel; even in the present-day scenes there is a sense of the past hovering, seeping into ordinary life. While Bui has self-deprecatingly referred to herself online as “the slowest cartoonist in America,” she is skilled at page layouts, delivering information deftly and imaginatively. As with her text, she accomplishes this without any undue fuss or “look-at-me” graphic pyrotechnics.

At the narrative’s end, Bui focuses on her now ten-year-old son, wondering if the pain she inherited from being a “product of war” will be transmitted to him: “whether I would pass along some gene for sorrow or unintentionally inflict damage I could never undo.” But she reminds us that life is, at heart, random, and that relationships are not necessarily bound by destiny but by free will and a dizzying array of events, most beyond our control. This final summation is deeply moving. Thematically rich and complex, melding together grief and hope, the personal and the political, the familial and the national, The Best We Could Do is an important, wise, and loving book.

A Christmas Carol Was Not His Best Holiday Novel, Charles Dickens Thought

His well-received novel that year wasn’t A Christmas Carol, the tale that modern audiences consider his quintessential yuletide work, but The Cricket on the Hearth, a story few readers beyond diehard Dickens fans recognize today.

Dickens (1812–1870) might be surprised by how little Cricket and his other holiday stories besides A Christmas Carol are read. After publishing Carol in 1843, he produced four other Christmas novels in quick succession, deeming some of his handiwork even more appealing than his iconic account of Ebenezer Scrooge.

When he published The Chimes, a follow-up to Carol for the 1844 holiday season, Dickens was sure he’d topped himself. “I believe I have written a tremendous Book; and knocked the Carol out of the field,” he told his friend Thomas Mitton. “It will make a great uproar, I have no doubt.”

But posterity has been less kind to Dickens’s non-Carol Christmas tales, which also include The Battle of Life (1846) and The Haunted Man (1848). A quick survey of Dickens’s holiday also-rans provides some clues about their lack of staying power.

The Chimes, in which the poor Englishman Trotty Veck is haunted by visions of oppressive poverty that serve as a form of moral instruction, seems obviously derivative of Carol, but without its memorable characters. Dickens biographer Angus Wilson, expressing what appears to be a critical consensus, lamented that this takedown “of a wicked social order never comes to life.”

The Cricket on the Hearth, about a miser named Tackleton who has a last-minute spiritual conversion, seems like warmed-over Carol, too—the nineteenth-century version of a by-the-numbers Hollywood sequel. The Battle of Life, a saccharine tale about a saintly maiden who allows her true love to marry her own sister, doesn’t even benefit from yuletide cheer, since the only holiday scene in the novel is an afterthought. Even Dickens seemed sick of the grind, at one point thinking of leaving Battle unfinished.

By the time he published The Haunted Man, yet another story of a spirit-addled misanthrope who turns over a new leaf, Dickens had clearly run out of steam with his Christmas series. Even his loyal fans were beginning to weary, not seeing the tortured main character, Professor Redlaw, as very compelling. Many readers, says Dickens biographer Michael Slater, “found the story of Redlaw’s emotional and spiritual journey both confused and confusing.”

On the whole, though, Dickens’s yuletide novels proved lucrative, a big reason he continued to write them. As Slater points out, “such keenly-anticipated annual productions from his pen were guaranteed money-spinners.”

“The market for a Christmas book from Dickens had been created,” biographer Claire Tomalin notes of the public mood after Cricket was released, “and the public now looked forward to getting one. If their quality declined—as it did . . . their sales increased.”

Though all but one of Dickens’s Christmas stories has lapsed into obscurity, even the lesser ones sometimes allowed him to explore themes he’d later perfect in more fully realized novels. The moral ambiguities of The Chimes, for example, seem to anticipate the Dickens classic Little Dorrit, Wilson writes.

What’s elevated Carol from the Christmas canon of Charles Dickens as its fellow yuletide narratives have faded? “It is just as much a compendium of the social obsessions that pressed upon Dickens so fiercely at this time,” writes Wilson, “but . . . the result is extraordinarily vivid, like some sermon acted out in a dream.”

If Dickens’s later Christmas novels prove nothing else, it’s that no holiday author has ever been able to top A Christmas Carol.

Not even Charles Dickens.

Literary experts look at why the classic Dickens' story 'A Christmas Carol' still draws us today

Tuesday Dec. 10, 2013

MANHATTAN -- Written 170 years ago, Charles Dickens' classic novella "A Christmas Story" still resonates with people today, according to two literature experts at Kansas State University.

The latest example of Dickens' enduring popularity will also be a nod to one of his most enduring works. A new film about Dickens' life, "The Invisible Woman," starring Ralph Fiennes, will be released on Christmas day.

"A Christmas Carol" features the penny-pinching, Christmas-hating Ebenezer Scrooge and his dramatic transformation after a timely visit from the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come.

Naomi Wood is a Kansas State University professor of English who specializes in children's and Victorian literature and culture. She says that "A Christmas Carol"has remained popular because of its observations about the holiday and its central theme that a person can always change.

"'A Christmas Carol' is a compelling story about the Christmas holiday not as a religious observance, but as an aspect of the social contract: the time when those who 'have' experience joy in sharing with those who 'have not,'" Wood said. "It's also a story of transformation. Scrooge's story offers the possibility that one can change for the better, become a better person and grow a bigger heart."

Dan Hoyt is a Kansas State University assistant professor of English who teaches Dickens' work. He said that "A Christmas Carol" also accurately captures sentiments that many people feel around the holidays, and gives a refreshing message amidst the commercialism that surrounds Christmas today.

"Much of Dickens' work, including 'A Christmas Carol,' has comic touches and is intensely sentimental. Just about everyone can appreciate those qualities during the holiday season," Hoyt said. "It champions generosity and compassion, and when Christmas feels commercialized in so many ways, that message is powerful and comforting."

Wood said that its compelling characters, as well as elements of the spooky and supernatural, add to the intrigue of "A Christmas Carol."

"The Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come are wonderful devices for thinking about our lives and what we want our legacy to be," Wood said. "The story also features a sweet and pathetic kid in Tiny Tim, as well as both a happy and unhappy ending. The double ending helps emphasize that we have a choice in how we affect the lives of others for better or worse."

"A Christmas Carol" has been adapted to many film versions, which Wood says would have pleased the author.

"Dickens was an avid theatergoer and was quite used to his novels being dramatized -- sometimes even before they were finished," she said. "He enjoyed seeing his work come to life on the stage, and I think if he would have lived long enough, he would have loved movies. He adapted his own work for public performance, and was renowned for his effective readings."

"Dickens' work still speaks to us on an emotional level," Hoyt said of the author's enduring popularity. "That's evident from the continual retellings and resurrections and re-imaginings of his fiction. 'A Christmas Carol,' for example, has been turned into everything from a ballet to a Broadway musical."

While many screen and stage versions of "A Christmas Carol" are quality adaptations of the novella, Wood said the one thing they sometimes leave out is the social criticism that is a prominent theme in the novella.

"The story is a feel-good parable about the joys of individual charity, but the book also demands its readers look at the vast economic system that produces 'want' and 'ignorance,' which Dickens personifies as society's hideous and starving children," she said. "Dickens wanted his readers to care about the 99 percent, and even more for the 47 percent -- the people who aren't served by the moneyed and privileged 1 percent."

"A Christmas Carol" was Dickens' first Christmas story. He made sure the book was published in time to sell for the holiday season in 1843, the year it was written. He would go on to write four more Christmas-themed novellas, as well as numerous shorter Christmas stories for magazines. Wood said Dickens was a big fan of the Christmas holiday and loved hosting parties with plenty of food, drinks, dancing and magic tricks.

"Dickens delighted in Christmas and having a big and roistering celebration with lots to eat and drink," she said. "He would have a big party for both kids and adults, and danced wildly with as many guests as possible. He was an enthusiastic amateur magician and loved to amaze his guests in made-up characters, such as 'The Unparalleled Necromancer Rhia Rhama Roos.'"

And as to my claim of it being lyrical, check out the appearance of the Ghost of Christmas Present:

And the ending always brings tears to my eyes if not outright weeping.

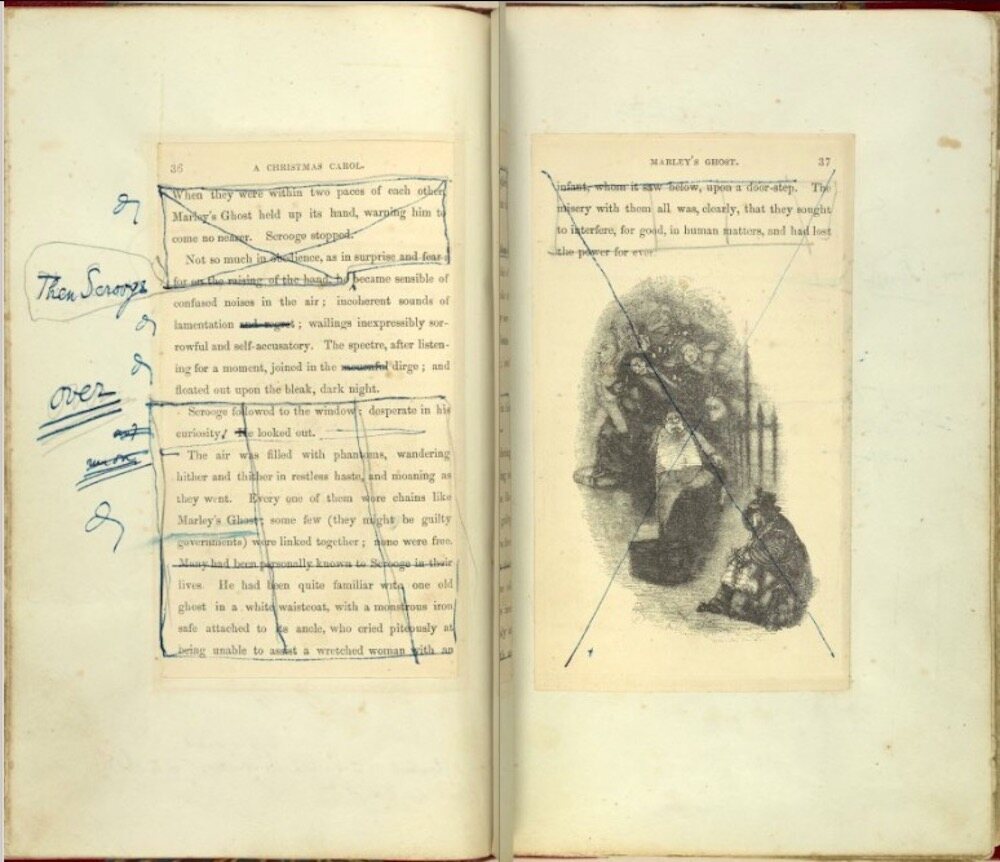

CHARLES DICKENS’S A CHRISTMAS CAROL, published in 1843, swiftly entered the holiday-season canon—the sort of story readers return to year after year, wherever there’s a crackling fire, a dusting of snow, and a mug of eggnog at hand. But when Dickens gave public readings from the text, the story changed a bit from one performance to another. His marked-up stage copy of the book, on view at the New York Public Library, gives readers a peek into the writer’s mind as he reworked his spirited prose.

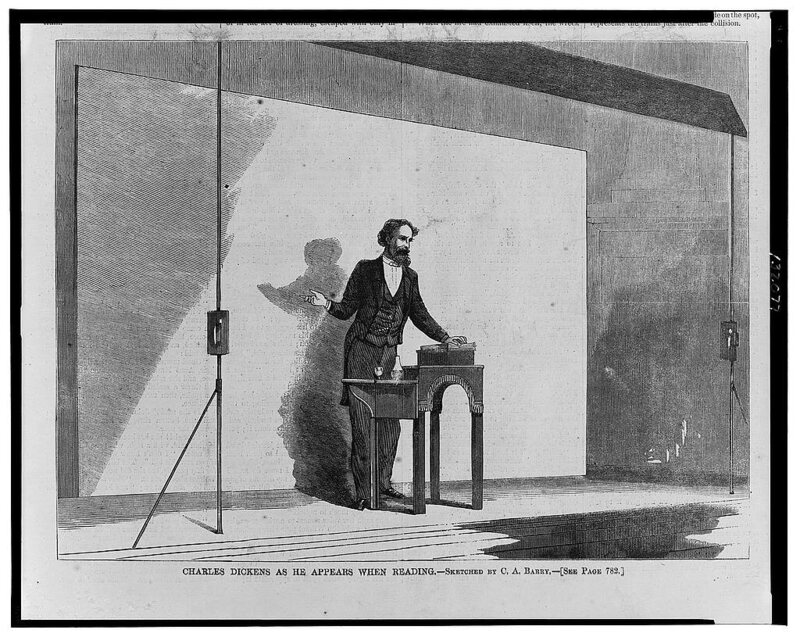

Dickens intuited that his devoted public would get a kick out of listening to him read from the already beloved text, and he spent decades taking his A Christmas Carol act on the road. He devised different voices and styles for each character, so Tiny Tim sounded nothing like Ebenezer Scrooge. Writers of the period commonly traveled to give lectures, but “reading from your own work was new, and his degree of literary celebrity took it into the stratosphere,” says Carolyn Vega, curator at the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library.

Dickens probably could have recited the whole story from memory, but the book itself was part of the appeal. “Even before he started the series of readings, he knew [the book] inside and out,” Vega says. “By the end of doing it for 20 years, he knew exactly what hooks the audience, what worked and what didn’t, but always went up with the book in hand. The idea of Dickens reading to you was the performance you were paying for.” He sat or stood behind a tall desk, with the volume always at hand—even if it was much too far from his face for the text to be easily decipherable.

The book was a prop and a prompt, and Dickens toted it with him and annotated it relentlessly. Over the years, Dickens wanted to fit stories beyond his Christmas fable into a single performance, which meant that each needed to shrink in order to fit into the allotted time. Dickens took a regular, off-the-shelf copy of A Christmas Carol, had the binding removed, and then set the pages onto larger ones, whose margins had plenty of room for notes.

Some of these are standard-issue edits, such as struck-through sentences or entire canceled paragraphs. (The text got leaner over time, Vega says.) Other notes evoke reminders like stage directions, such as a note about conjuring a specific tone. Dickens reminded himself to convey a sense of “mystery” just before Scrooge spots Marley’s ghostly face in his door knocker, and to sound “cheerful” when channeling warm tidings from the humbug’s nephew. In edits to another text he performed, Vega says, “he reminds himself that the tone should be ‘very pathetic,’ circled and written large.”

The edits also offer a window into Dickens’s speedy working style. The author often worked serially, submitting stories under deadline pressure, and “you get a sense of that energy when you look at the prompt copy,” Vega says. Some pages have blots and smudges, indicating that he was working fast, loose, and frantically, without waiting for the ink to dry. Until January 7, 2019, library visitors can take a look at Dickens’s copy, and see that a writer’s work is never really done.Some twenty years before Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, another animated entertainment injected “the most wonderful time of the year” with a potent dose of horror.

Surely I’m not the only child of the 70s to have been equal parts mesmerized and stricken by director Richard Williams’ faithful, if highly condensed, interpretation of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

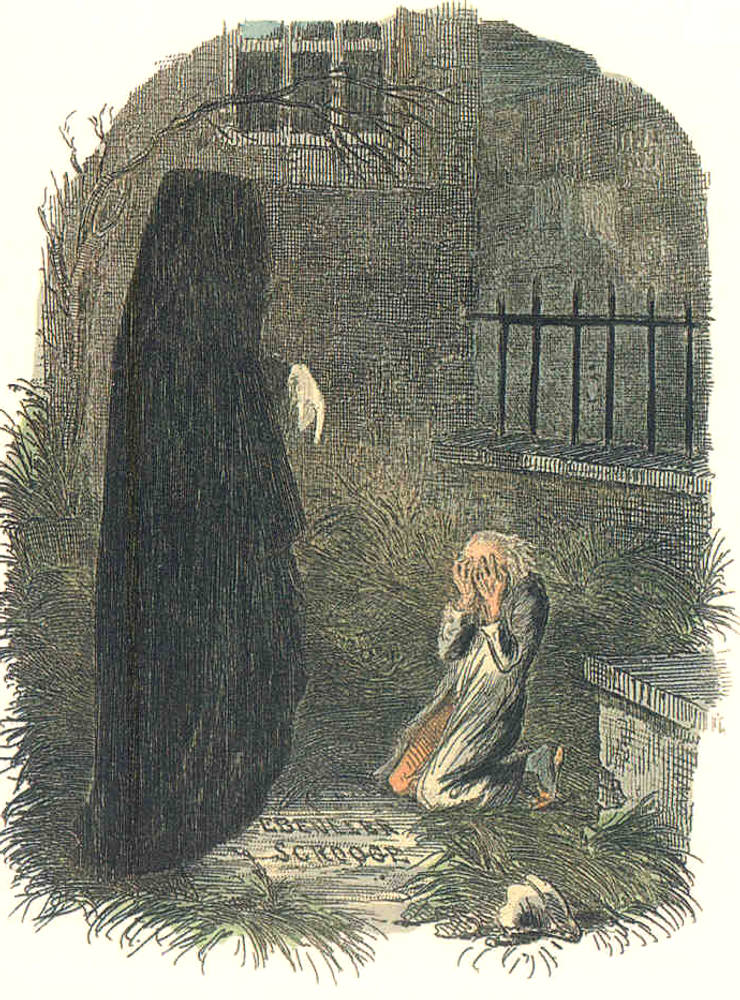

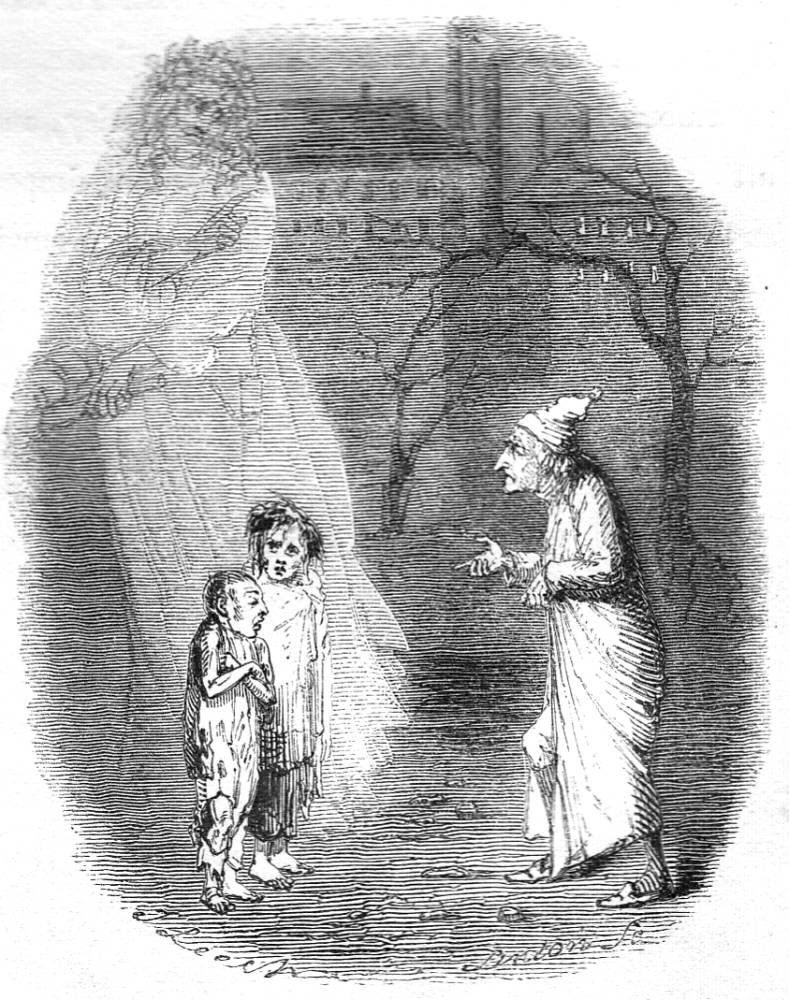

The 25-minute short features a host of hair-raising images drawn directly from Dickens’ text, from a spectral hearse in Scrooge’s hallway and the Ghost of Marley’s gaping maw, to a night sky populated with miserable, howling phantoms and the monstrous children lurking beneath the Ghost of Christmas Present’s skirts:

Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread… This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.

Producer Chuck Jones, whose earlier animated holiday special, Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, is in keeping with his classic work on Bugs Bunny and other Warner Bros. faves, insisted that this cartoon should mirror the look of the John Leech steel engravings illustrating Dickens’ 1843 original.

D.T. Nethery, a former Disney animation artist and fan of this Christmas Carol explains that the desired Victorian look was achieved with a labor-intensive process that involved drawing directly on cels with Mars Omnichrom grease pencil, then painting the backs and photographing them against detailed watercolored backgrounds.

As director Williams recalls below, he and a team including master animators Ken Harris and Abe Levitow were racing against an impossibly tight deadline that left them pulling 14-hour days and 7-day work weeks. Reportedly, the final version was completed with just an hour to spare. (“We slept under our desks for this thing.”)

As Michael Lyons observes in Animation Scoop, the exhausted animators went above and beyond

As Michael Lyons observes in Animation Scoop, the exhausted animators went above and beyond with Jones’ request for a pan over London’s rooftops, “making the entire twenty-five minutes of the short film take on the appearance of art work that has come to life”:

…there are scenes that seem to involve camera pans, or sequences in which the camera seemingly circles around the characters. Much of this involved not just animating the characters, but the backgrounds as well and in different sizes as they move toward and away from the frame. The hand-crafted quality, coupled with a three-dimensional feel in these moments, is downright tactile.

Revered British character actors Alistair Sim (Scrooge) and Michael Hordern (Marley’s Ghost) lent some extra class, reprising their roles from the evergreen, black-and-white 1951 adaptation.

The short’s television premiere caused such a sensation that it was given a subsequent theatrical release, putting it in the running for an Oscar for Best Animated Short Subject. (It won, beating out Tup-Tup from Croatia and the NSFW-ish Kama Sutra Rides Again which Stanley Kubrick had handpicked to play before A Clockwork Orange in the UK.)

With theaters in Dallas, Los Angeles, Portland, Providence, Tallahassee and Vancouver cancelling planned live productions of A Christmas Carol out of concern for the public health during this latest wave of the pandemic, we’re happy to get our Dickensian fix, snuggled up on the couch with this animated 50-year-old artifact of our childhood….

Related Content:

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just as Dickens Read It

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol, A Vintage Radio Broadcast by Orson Welles (1939)

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primaologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/charles-dickens-christmas-carol-scrooge-book-gift-exhibition-a6777341.html

Charles Dickens' gift to the world was Christmas Carol, but what does it still mean to us?

‘A Christmas Carol’ exposed poverty and gave us an image of Christmas that still endures. As an exhibition about the book opens, we look at what it still means to us

For many of us, Christmas – in our imaginations at least – is a distinctly Dickensian affair. Candlelit tables are laden with succulent roast birds and flaming puddings, merry carollers wend their way along snowy streets, families gather harmoniously for fireside stories and games.

The reality may well be more shop-bought, drizzly and fractious, but our Christmas cards, advent calendars and television series (this year the BBC is offering Dickensian, a mash-up of the author’s characters) attest to our rather romantic seasonal attachment to all things Victorian.

|

| Albert Finney was both young and old in the 1970 musical film version |

A Christmas Carol, published on 19 December 1843, was an instant success. The first run of 6,000 copies sold out by Christmas Eve. In print ever since, it has also spawned countless adaptations for stage, screen and song. The miserly Ebenezer Scrooge – joyously transformed by the visitations of the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come – has been portrayed by Alastair Sim, Albert Finney, Michael Caine, Marcel Marceau, Jim Carrey and, currently, Jim Broadbent in a West End production. Set to join the list in 2017 is rapper Ice Cube.

It has often been said that, in this much-loved story, Dickens invented Christmas as we know it today. Louisa Price, curator of the Charles Dickens Museum – based in the author’s first London family home and decorated for weeks now in a traditional Dickensian Christmas style – says that while A Christmas Carol was instantly influential, the truth is less straightforward.

“He clearly taps into a lot of traditions that we still hold dear: families getting together, wintry weather, special atmosphere, cosy gatherings. It is a story about compassion and good will at Christmas and we still gravitate towards this sort of tale. The book definitely put Dickens centre-stage at Christmas.”

That the festival was hitherto non-existent is, though, inaccurate. “Dickens made Christmas fashionable again, but it was celebrated well before his time,” says Price. “Always popular with the masses, it had fallen out of favour among the metropolitan middle-classes.”

During the 18th and early-19th centuries, industrialisation had transformed the nation. “People were moving from rural communities – perhaps centred round a stately home – and moving into the city,” explains Price. “Nuclear family became more important. People were working longer hours and they had less time off over the season. The way society gathered had changed.”

There was, Price says, an established market for seasonal publications, with two almanacs, Forget Me Not and The Keepsake, popular since the 1820s. Dickens took the genre to a new level. “He undercut them, making Carol cheaper but really investing in the presentation, with a cinnamon cloth binding and beautiful illustrations by John Leech.”

Literary circles were charmed. The author of Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray, declared that the novella “occasioned immense hospitality throughout England; was the means of lighting up hundreds of kind fires at Christmas time; caused a wonderful outpouring of Christmas good feeling...”

Celebrated letter-writer Jane Carlyle notes that after reading the book, her husband, the historian and essayist Thomas Carlyle, dispatched her to buy their first turkey.

Yet while A Christmas Carol is Dickens’ best-known festive story – and his most successful – it was not his first. In 1835 he had published A Christmas Dinner – a lively depiction of the big meal, complete with timeless concerns about family politics – and in the 24 years after 1843, he produced 22 further seasonal stories.“That man must be a misanthrope indeed, in whose breast something like a jovial feeling is not roused – in whose mind some pleasant associations are not awakened – by the recurrence of Christmas,” he wrote in 1835.

Clearly, says Price, the man loved Christmas. “He came from a family with strong traditions of gathering together and doing a lot of the things that are described in the Carol.” Many of the scenes in A Christmas Carol reflected those in his life. Extended family and friends were welcomed, the house and table were decorated with evergreens, toasts were raised and parlour games and homespun shows – Dickens himself performed magic tricks for the children, Blind Man’s Buff was another favourite – were encouraged.

“One of Dickens’ daughters recalled him taking them down to a toyshop in Holborn and patiently waiting for them to choose their gift for Christmas,” says Price. Oldest son Charley remembered being brought down from the nursery to fill a place at one festive feast after the non-appearance of an expected guest.

As we see in the metamorphosis of Scrooge and the touching celebrations of the Cratchits – poor and worried for disabled Tiny Tim – Christmas was to Dickens also a time for gratitude, generosity and hope.

“Reflect upon your present blessings – of which every man has many – not on your past misfortunes, of which all men have some. Fill your glass again, with a merry face and contented heart. Our life on it, but your Christmas shall be merry, and your new year a happy one!” he wrote in A Christmas Dinner.

The moral behind A Christmas Carol is clear and intentional, though. Dickens’ outrage at the conditions faced by Britain’s poor is well-known. The story was his inspired way of highlighting the problem and exhorting the rich to action.

Earlier in 1843, the findings of a Parliamentary report into child labour had shocked Dickens. He also toured a Ragged School in London’s Clerkenwell and visited his sister Fanny (whose son is thought to have been the inspiration for Tiny Tim) in Manchester.

“He was incensed,” says Price, “and decided he would publish a political pamphlet called Benefit of the Poor Man’s Child. Within days, though, he tells friends he will defer his action until Christmas and that the result will be 20 times more powerful.”

He began writing in October, completing the story in six weeks. The book was intended to be read aloud, something he himself first did publicly that year and continued to do until 1870, the year of his death.

The traditions of the celebrations remained largely relevant then as they do now. In 1843, turkey – such as the giant one Scrooge has sent to the home of the Cratchits, having seen their meagre Christmas Day goose – was an emerging trend, imported from the New World.

Dickens received turkeys – as well as pork pies and ducks – from friends including his lawyer, publisher and his benefactor Angela Burdett-Coutts, the latter’s bird so large, he writes, that he initially mistook it for a baby.

This was also the year in which Christmas cards were first sent, the mass production of many printed goods being a result of industrialisation. Their wording is reflected in Scrooge’s happy declaration of “A merry Christmas to every-body! A happy New Year to all the world!”

It is this message – of compassion and goodwill – that Price believes underpins our continuing affection for Dickens at Christmas. Alongside the wintry imagery, the mouth-watering feasts and the cosy firesides, we are heartened by Scrooge’s eventual humility and generosity.

This year, the Charles Dickens Museum has asked illustration students from Central Saint Martins to create pieces inspired by A Christmas Carol. Many of them, says Price, have applied his words to 21st-century issues. “Responses to the refugee crisis, homelessness, ethical manufacturing all seem relevant. Perhaps, in the face of increasing commercialisation, we are looking for a more thoughtful message for Christmas.”

For details of Christmas events at the Charles Dickens museum see dickensmuseum.com

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2112.19 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2361 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment