A Sense of Doubt blog post #2465 - OPEN CULTURE STUFF

I have been on an Open Culture kick lately.

Enjoy!!

https://www.openculture.com/2011/09/open_culture_beat_no_9.html

What cultural goodies did we tweet (and re-tweet) on our Twitter stream in recent days? Here are the highlights. Follow us on Twitter at @openculture to get the rest, or Like us on Facebook. We’ll keep you plugged into quality culture every day.

What cultural goodies did we tweet (and re-tweet) on our Twitter stream in recent days? Here are the highlights. Follow us on Twitter at @openculture to get the rest, or Like us on Facebook. We’ll keep you plugged into quality culture every day.

- Haruki Murakami’s New Story, “Town of Cats.” Published in last week’s New Yorker.

- 10 Things Henri Cartier-Bresson Can Teach You About Street Photography. Here it goes.

- Paul Simon Performs ‘Sound of Silence.’ A somber and fitting performance at the 9/11 Memorial.

- Read J.D. Salinger’s Words Before They Disappear. Backstory here. Actual Salinger letter here.

- Listen to a Free Audiobook of The 9/11 Commission Report. Plus other related materials. Audio.

- Agatha Christie and Her Surf Board, 1922. Groovy photo.

- Understanding Dostoyevsky Courtesy of Woody Allen: It’s all about existentialism.

- Hubble Captures Time-Lapse Videos Of Stars Being Born. Mind-blowing NASA video.

- Stream Music Courtesy of the David Lynch Foundation. Listen to original music by Alanis Morissette, Tom Waits, Dave Stewart, etc.

- Joan Didion’s “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream.” Now online.

- Salvador Dali’s Vogue Covers. Produced mostly in the 1930s and 40s.

- Jonathan Lethem Introduces Lost Rolling Stone Interview with Clint Eastwood. Read it here.

- Ernest Hemingway’s Early Life in Letters. Vintage photos.

- Photo of Katharine Hepburn after the Hurricane of 1938. Click images to enlarge.

- Frank Zappa Speaks Out for Dental Hygiene. A humorous public service announcement circa 1981.

- Louis CK Pays Tribute to George Carlin at The New York Public Library. A little NSFW, of course!

- Malcolm Gladwell: How Different are Dogfighting and Football? His latest in The New Yorker. Text.

- Letter of Recommendation Written for 16 Year Old Orson Welles. “He’s talented to the point of genius.”

- Hannah Arendt’s Challenge to Adolf Eichmann. Judith Butler writes in The Guardian.

- The Best Muppet Show Beatles Covers. Fun.

- Amazing Shot of the Surface of Mars. Captured by the Rover Opportunity on Aug 9.

- 30 Amazing Stanley Kubrick Cinemagraphs. Photos.

- Leonardo Mural in Florence, a Lost Masterpiece, May Soon Be Revealed. The story

- Space Oddity, A Children’s Book Inspired By David Bowie’s Classic Song. Image collection here.

- Steven Soderbergh to Leave Hollywood. Confirms plans to become a painter.

- A History of Ireland in 100 Objects. Starts with Mesolithic Fish Trap, ca. 5000BC

Sources: @matthiasrascher, @kottke, @coudal, @craigmod, @thebookslut, @thedailyMUBI, @brainpicker, @Criterion, @ebertchicago

SO MANY GREAT LINKS...https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/meet-the-mysterious-genius-who-patented-the-ufo.html

This one was blog post #2464:

A Sense of Doubt blog post #2464 - Meet the Mysterious Genius who Patented the UFO

Bertrand Russell’s Ten Commandments for Living in a Healthy Democracy

https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/bertrand-russells-ten-commandments-for-living-in-a-healthy-democracy.html

Bertrand Russell saw the history of civilization as being shaped by an unfortunate oscillation between two opposing evils: tyranny and anarchy, each of which contain the seed of the other. The best course for steering clear of either one, Russell maintained, is liberalism.

“The doctrine of liberalism is an attempt to escape from this endless oscillation,” writes Russell in A History of Western Philosophy. “The essence of liberalism is an attempt to secure a social order not based on irrational dogma [a feature of tyranny], and insuring stability [which anarchy undermines] without involving more restraints than are necessary for the preservation of the community.”

In 1951 Russell published an article in The New York Times Magazine, “The Best Answer to Fanaticism–Liberalism,” with the subtitle: “Its calm search for truth, viewed as dangerous in many places, remains the hope of humanity.” In the article, Russell writes that “Liberalism is not so much a creed as a disposition. It is, indeed, opposed to creeds.” He continues:

But the liberal attitude does not say that you should oppose authority. It says only that you should be free to oppose authority, which is quite a different thing. The essence of the liberal outlook in the intellectual sphere is a belief that unbiased discussion is a useful thing and that men should be free to question anything if they can support their questioning by solid arguments. The opposite view, which is maintained by those who cannot be called liberals, is that the truth is already known, and that to question it is necessarily subversive.

Russell criticizes the radical who would advocate change at any cost. Echoing the philosopher John Locke, who had a profound influence on the authors of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, Russell writes:

The teacher who urges doctrines subversive to existing authority does not, if he is a liberal, advocate the establishment of a new authority even more tyrannical than the old. He advocates certain limits to the exercise of authority, and he wishes these limits to be observed not only when the authority would support a creed with which he disagrees but also when it would support one with which he is in complete agreement. I am, for my part, a believer in democracy, but I do not like a regime which makes belief in democracy compulsory.

Russell concludes the New York Times piece by offering a “new decalogue” with advice on how to live one’s life in the spirit of liberalism. “The Ten Commandments that, as a teacher, I should wish to promulgate, might be set forth as follows,” he says:

1: Do not feel absolutely certain of anything.

2: Do not think it worthwhile to produce belief by concealing evidence, for the evidence is sure to come to light.

3: Never try to discourage thinking, for you are sure to succeed.

4: When you meet with opposition, even if it should be from your husband or your children, endeavor to overcome it by argument and not by authority, for a victory dependent upon authority is unreal and illusory.

5: Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found.

6: Do not use power to suppress opinions you think pernicious, for if you do the opinions will suppress you.

7: Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

8: Find more pleasure in intelligent dissent than in passive agreement, for, if you value intelligence as you should, the former implies a deeper agreement than the latter.

9: Be scrupulously truthful, even when truth is inconvenient, for it is more inconvenient when you try to conceal it.

10. Do not feel envious of the happiness of those who live in a fool’s paradise, for only a fool will think that it is happiness.

Wise words then. Wise words now.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in March, 2013.

Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere.

Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox.

Related Content:

Bertrand Russell: The Everyday Benefit of Philosophy Is That It Helps You Live with Uncertainty

Bertrand Russell Authority and the Individual (1948)

What Is Sun Tzu’s The Art of War About?: A Short Introduction

https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/what-is-sun-tzus-the-art-of-war-about-a-short-introduction.html

After wars in Japan and Vietnam, the U.S. military became quite keen on a slim volume of ancient Chinese literature known as The Art of War by a supposedly historical general named Sun Tzu. This book became required reading at military academies and a favorite of law enforcement, and has formed a basis for strategy in modern wartime — as in the so-called “Shock and Awe” campaigns in Iraq. But some have argued that the Western adoption of this text — widely read across East Asia for centuries — neglects the crucial context of the culture that produced it.

Despite historical claims that Sun Tzu served as a general during the Spring and Autumn period, scholars have mostly doubted this history and date the composition of the book to the Warring States period (circa 475-221 B.C.E.) that preceded the first empire, a time in which a few rapacious states gobbled up their smaller neighbors and constantly fought each other.

“Occasionally the rulers managed to arrange recesses from the endemic wars,” translator Samuel B. Griffith notes. Nonetheless, “it is extremely unlikely that many generals died in bed during the hundred and fifty years between 450 and 300 B.C.”

The author of The Art of War was possibly a general, or one of the many military strategists for hire at the time, or as some scholars believe, a compiler of an older oral tradition. In any case, constant warfare was the norm at the time of the book’s composition. This tactical guide differs from other such guides, and from those that came before it. Rather than counseling divination or the study of ancient authorities, Sun Tzu’s advice is purely practical and of-the-moment, requiring a thorough knowledge of the situation, the enemy, and oneself. Such knowledge is not easily acquired. Without it, defeat or disaster are nearly certain:

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

The kind of knowledge Sun Tzu recommends is practical intelligence about troop deployments, food supplies, etcetera. It is also knowledge of the Tao — in this case, the general moral principle and its realization through the sovereign. In a time of Warring States, Sun Tzu recognized that knowledge of warfare was “a matter of vital importance”; and that states should undertake it as little as possible.

“To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill,” The Art of War famously advises. Diplomacy, deception, and indirection are all preferable to the material waste and loss of life in war, not to mention the high odds of defeat if one goes into battle unprepared. “The ideal strategy of restraint, of winning without fighting… is characteristic of Taoism,” writes Rochelle Kaplan. “Both The Art of War and the Tao Te Ching were designed to help rulers and their assistants achieve victory and clarity,” and “each of them may be viewed as anti-war tracts.”

Read a full translation of The Art of War by Lionel Giles, in several formats online here, and just above, hear the same translation read aloud.

Related Content:

Life-Changing Books: Your Picks

“The Philosophy of “Flow”: A Brief Introduction to Taoism

When Sci-Fi Legend Ursula K. Le Guin Translated the Chinese Classic, the Tao Te Ching

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/how-the-worlds-first-anti-vax-movement-started-with-the-first-vaccine-for-smallpox-in-1796-and-spread-fears-of-people-getting-turned-into-half-cow-babies.html

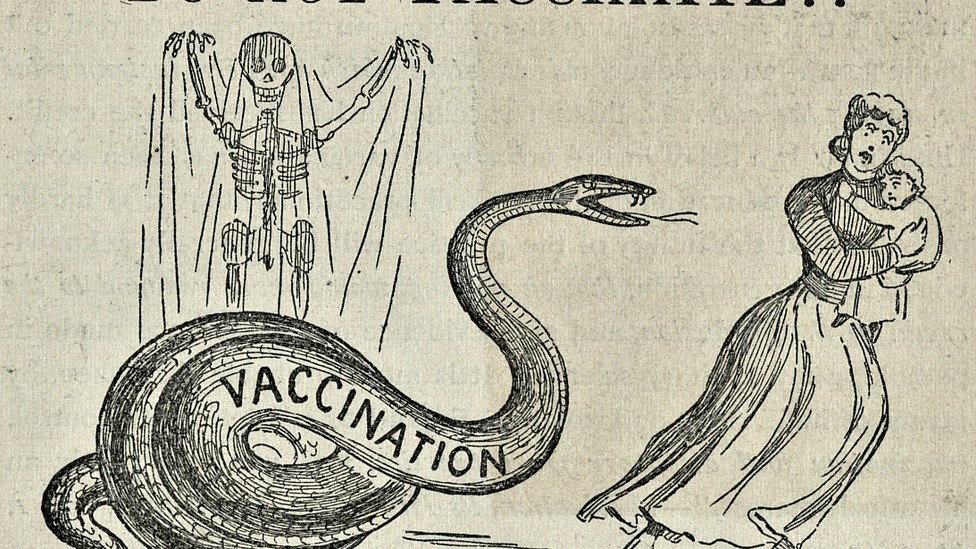

A cartoon from a December 1894 anti-vaccination publication (Courtesy of The Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia)

For well over a century people have queued up to get vaccinated against polio, smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, the flu or other epidemic diseases. And they have done so because they were mandated by schools, workplaces, armed forces, and other institutions committed to using science to fight disease. As a result, deadly viral epidemics began to disappear in the developed world. Indeed, the vast majority of people now protesting mandatory vaccinations were themselves vaccinated (by mandate) against polio, smallpox, measles, mumps, rubella, etc., and hardly any of them have contracted those once-common diseases. The historical argument for vaccines may not be the most scientific (the science is readily available online). But history can act as a reliable guide for understanding patterns of human behavior.

In 1796, Scottish physician Edward Jenner discovered how an injection of cowpox-infected human biological material could make humans immune to smallpox. For the next 100 years after this breakthrough, resistance to inoculation grew into “an enormous mass movement,” says Yale historian of medicine Frank Snowden. “There was a rejection of vaccination on political grounds that it was widely considered as another form of tyranny.”

Fears that injections of cowpox would turn people into mutants with cow-like growths were satirized as early as 1802 by cartoonist James Gilray (below). While the anti-vaccination movement may seem relatively new, the resistance, refusal, and denialism are as old as vaccinations to infectious disease in the West.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

“In the early 19th century, British people finally had access to the first vaccine in history, one that promised to protect them from smallpox, among the deadliest diseases in the era,” writes Jess McHugh at The Washington Post. Smallpox killed around 4,000 people a year in the UK and left hundreds more disfigured or blinded. Nonetheless, “many Britons were skeptical of the vaccine…. The side effects they dreaded were far more terrifying: blindness, deafness, ulcers, a gruesome skin condition called ‘cowpox mange’ — even sprouting hoofs and horns.” Giving a person one disease to frighten off another one probably seemed just as absurd a notion as turning into a human/cow hybrid.

Jenner’s method, called variolation, was outlawed in 1840 as safer vaccinations replaced it. By 1867, all British children up to age 14 were required by law to be vaccinated against smallpox. Widespread outrage resulted, even among prominent physicians and scientists, and continued for decades. “Every day the vaccination laws remain in force,” wrote scientist Alfred Russel Wallace in 1898, “parents are being punished, infants are being killed.” In fact, it was smallpox claiming lives, “more than 400,000 lives per year throughout the 19th century, according to the World Health Organization,” writes Elizabeth Earl at The Atlantic. “Epidemic disease was a fact of life at the time.” And so it is again. Covid has killed almost 800,000 people in the U.S. alone over the past two years.

Then as now, medical quackery played its part in vaccine refusal — in this case a much larger part. “Never was the lie of ‘the good old days’ more clear than in medicine,” Greig Watson writes at BBC News. “The 1841 UK census suggested a third of doctors were unqualified.” Common causes of illness in an 1848 medical textbook included “wet feet,” “passionate fear or rage,” and “diseased parents.” Among the many fiery lectures, caricatures, and pamphlets issued by opponents of vaccination, one 1805 tract by William Rowley, a member of the Royal College of Physicians, alleged that the injection of cowpox could mar an entire bloodline. “Who would marry into any family, at the risk of their offspring having filthy beastly diseases?” it asked hysterically.

Then, as now, religion was a motivating factor. “One can see it in biblical terms as human beings created in the image of God,” says Snowden. “The vaccination movement injecting into human bodies this material from an inferior animal was seen as irreligious, blasphemous and medically wrong.” Granted, those who volunteered to get vaccinated had to place their faith in the institutions of science and government. After medical scandals of the recent past like the Tuskegee experiments or Thalidomide, that can be a big ask. In the 19th century, says medical historian Kristin Hussey, “people were asking questions about rights, especially working-class rights. There was a sense the upper class were trying to take advantage, a feeling of distrust.”

The deep distrust of institutions now seems intractable and fully endemic in our current political climate, and much of it may be fully warranted. But no virus has evolved — since the time of the Jenner’s first smallpox inoculation — to care about our politics, religious beliefs, or feelings about authority or individual rights. Without widespread vaccination, viruses are more than happy to exploit our lack of immunity, and they do so without pity or compunction.

Related Content:

Dying in the Name of Vaccine Freedom

How Vaccines Improved Our World In One Graphic

How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How Stanley Kubrick Made 2001: A Space Odyssey: A Seven-Part Video Essay

https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/how-stanley-kubrick-made-2001-a-space-odyssey-a-seven-part-video-essay.html

Andrei Tarkovsky had a rather low opinion of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. “Phony on many points,” he once called it, built on “a lifeless schema with only pretensions to truth.” His professional response was 1972’s Solaris, by most estimates another high point in the science-fiction cinema of that period. Yet today it isn’t widely regarded as Tarkovsky’s best work; certainly it hasn’t become as much of an object of worship as, say, Stalker. That picture — arguably another work of sci-fi, though one sui generis in practically its every facet — continues to inspire such tributes and exegeses as the video essay on its making we featured earlier this year here on Open Culture.

That video essay came from the channel of Youtuber CinemaTyler, who like many auteur-oriented cinephiles exhibits appreciation for Tarkovsky and Kubrick alike. He’s created numerous examinations on the work that went into Kubrick’s pictures, including A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, and Full Metal Jacket.

The ambition of 2001, outsized even by Kubrick’s standard, is reflected in what it spurred CinemaTyler on to create: a seven-part series of video essays on its production, with three-hour total runtime that far exceeds that of the film itself. It takes at least that long to explain the achievements Kubrick pulled off, especially with mid-1960s filmmaking technology, which gave us the rare vision of the future that has held up for more than half a century.

Some of the qualities that have made 2001 endure came into being almost by accident. Take the use of Strauss’ “The Blue Danube” to introduce the space station, a stroke of scoring genius inspired by the records Kubrick and company happened to be listening to while viewing their footage. That and other classical pieces replaced an original score by the composer who’d worked on Kubrick’s Spartacus, which would have struck a different mood altogether. So would the portentous narration included in earlier versions of the script, hardly imaginable in the context of such powerfully wordless scenes as the famous four-million-year cut from tossed bone to spacecraft, which turns out to have been originally conceived an Earth-orbiting nuclear-weapon platform. That’s one of the many little-known facts CinemaTyler fits into this series, and a viewing of which even the biggest Kubrick buffs will have reason to admire 2001 more intensely than ever.

Related Content:

1966 Film Explores the Making of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (and Our High-Tech Future)

James Cameron Revisits the Making of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

The Story of Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Troubled (and Even Deadly) Sci-Fi Masterpiece

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Albert Einstein in Four Color Films

https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/albert-einstein-in-four-color-films.html

We all think we know just what Albert Einstein looked like — and broadly speaking, we’ve got it right. At least since his death in 1955, since which time generation after generation of children around the world have grown up closely associating his bristly mustache and semi-tamed gray hair with the very concept of scientific genius. His sartorial rumpledness and Teutonically hangdog look have long been the stuff of not just caricature, but (as in Nicolas Roeg’s Insignificance) earnest tribute as well. Yet how many of us can say we’ve really taken a good look at Einstein?

These four pieces of film get us a little closer to that experience. At the top of the post we have a colorized newsreel clip (you can see the original here) showing Einstein in his office at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, where he took up a post in 1933.

Even earlier colorized newsreel footage appears in the video just above, taken from an episode of the Smithsonian Channel series America in Color. It depicts Einstein arriving in the United States in 1930, by which time he was already “the world’s most famous physicist” — a position then meriting a welcome not unlike that which the Beatles would receive 34 years later.

Einstein returned to his native Germany after that visit. The America in Color clip also shows him back at his cottage outside Berlin (and in his pajamas), but his time back in his homeland amounted only to a few years. The reason: Hitler. During Einstein’s visiting professorship at Cal Tech in 1933, the Gestapo raided his cottage and Berlin apartment, as well as confiscated his sailboat. Later the Nazi government banned Jews from holding official positions, including at universities, effectively cutting off his professional prospects and those of no few other German citizens besides. The 1943 color footage above offers a glimpse of Einstein a decade into his American life.

A couple of years thereafter, the end of the Second World War made Einstein even more famous. He became, in the minds of many Americans, the brilliant physicist who “helped discover the atom bomb.” So declares the announcer in that first newsreel, but in the decades since, the public has come to associate Einstein more instinctively with his theory of relativity — an achievement less immediately comprehensible than the apocalyptic explosion of the atomic bomb, but one whose scientific implications run much deeper. Many clear and lucid précis of Einstein’s theory exist, but why not first see it explained by the man himself, and in color at that?

Related Content:

Newly Unearthed Footage Shows Albert Einstein Driving a Flying Car (1931)

Hear Albert Einstein Read “The Common Language of Science” (1941)

Marilyn Monroe Explains Relativity to Albert Einstein (in a Nicolas Roeg Movie)

When Albert Einstein & Charlie Chaplin Met and Became Fast Famous Friends (1930)

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity Explained in One of the Earliest Science Films Ever Made (1923)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

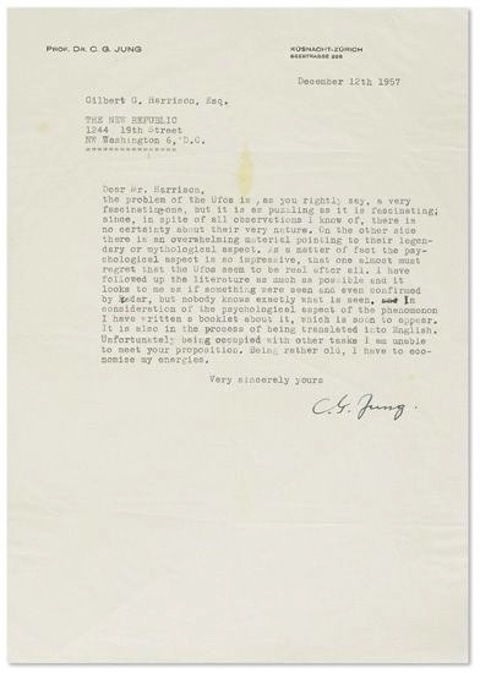

Carl Jung’s Fascinating 1957 Letter on UFOs

https://www.openculture.com/2013/05/carl_jungs_1957_letter_on_the_fascinating_modern_myth_of_ufos.html

Deities, conspiracies, politics, space aliens: you don’t actually have to believe in these to find them interesting. Just focus your attention not on the things themselves, but in how other people regard them, what they say when they talk about them, and why they think about them the way they do. Psychotherapist and onetime Freud protégé Carl Gustav Jung treated UFOs this way when he wrote his book Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies, which examines “not the reality or unreality” of the titular phenomena, but their “psychic aspect,” and “what it may signify that these phenomena, whether real or imagined, are seen in such numbers just at a time” — the Cold War — “when humankind is menaced as never before in history.” As what Jung called a “modern myth,” UFOs qualify as real indeed.

In 1957, with Flying Saucers to appear the following year, New Republic editor Gilbert A. Harrison wanted to get this Jungian perspective on UFOs in his magazine. At the top of this post, you can see (via The Awl) a scan of Jung’s response to Harrison’s query, the text of which follows:

the problem of the Ufos is, as you rightly say, a very fascinating one, but it is as puzzling as it is fascinating; since, in spite of all observations I know of, there is no certainty about their very nature. On the other side, there is an overwhelming material pointing to their legendary or mythological aspect. As a matter of fact the psychological aspect is so impressive, that one almost must regret that the Ufos seem to be real after all. I have followed up the literature as much as possible and it looks to me as if something were seen and even confirmed by radar, but nobody knows exactly what is seen. In consideration of the psychological aspect of the phenomenon I have written a booklet about it, which is soon to appear. It is also in the process of being translated into English. Unfortunately being occupied with other tasks I am unable to meet your proposition. Being rather old, I have to economize my energies.

Jung, as you can see, doubled his own interest in the subject by not only considering flying saucers a social phenomenon, but as a real physical phenomenon as well. Serious enthusiasts of both Jung and UFOs might consider bidding on the original letter, now up for auction. Estimated sale price: $2,000 to 3,000.

Related Content:

Face to Face with Carl Jung: ‘Man Cannot Stand a Meaningless Life’

Carl Gustav Jung Explains His Groundbreaking Theories About Psychology in Rare Interview (1957)

Carl Gustav Jung Ponders Death

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

How Led Zeppelin Stole Their Way to Fame and Fortune

https://www.openculture.com/2021/11/how-led-zeppelin-stole-their-way-to-fame-and-fortune.html

When Bob Dylan released his 2001 album Love and Theft, he lifted the title from a book of the same name by Eric Lott, who studied 19th century American popular music’s musical thefts and contemptuous impersonations. The ambivalence in the title was there, too: musicians of all colors routinely and lovingly stole from each other while developing the jazz and blues traditions that grew into rock and roll. When British invasion bands introduced their version of the blues, it only seemed natural that they would continue the tradition, picking up riffs, licks, and lyrics where they found them, and getting a little slippery about the origins of songs. This was, after all, the music’s history.

In truth, most UK blues rockers who picked up other people’s songs changed them completely or credited their authors when it came time to make records. This may not have been tradition but it was ethical business practice. Fans of Led Zeppelin, on the other hand, now listen to their music with asterisks next to many of their hits — footnotes summarizing court cases, misattributions, and downright thefts from which they profited. In many cases, the band would only admit to stealing under duress. At other times, they freely confessed in interviews to taking songs, tweaking them a bit, and giving themselves sole credit for composing and/or arranging.

A list of ten “rip offs” in a Rolling Stone piece on Led Zeppelin’s penchant for theft is hardly exhaustive. It does not include “Stairway to Heaven,” for which the band was recently sued for lifting a melody from Spirit’s “Taurus.” (An internet user saved the band’s case by finding that both songs used an earlier melody from the 1600s.)

During those recent court proceedings, the prosecution quoted from a 1993 interview Jimmy Page gave Guitar World:

“[A]s far as my end of it goes, I always tried to bring something fresh to anything that I used. I always made sure to come up with some variation. In fact, I think in most cases, you would never know what the original source could be. Maybe not in every case – but in most cases. So most of the comparisons rest on the lyrics. And Robert was supposed to change the lyrics, and he didn’t always do that – which is what brought on most of the grief. They couldn’t get us on the guitar parts of the music, but they nailed us on the lyrics.”

The blame shifting was “not quite fair to Plant,” the court found, “as Page repeatedly took entire musical compositions without attribution.” He stood accused of doing so, for example, in “The Lemon Song,” lifted from Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor.” After a lawsuit, the song is now co-credited to Chester Burnett (Howlin’ Wolf’s real name). For his part, Plant readily blamed Page when given the chance. In his book Led Zeppelin IV, Barney Hoskyns quotes the singer’s thoughts on the “Whole Lotta Love” controversy:

I think when Willie Dixon turned on the radio in Chicago twenty years after he wrote his blues, he thought, ‘That’s my song.’ … When we ripped it off, I said to Jimmy, ‘Hey, that’s not our song.’ And he said, ‘Shut up and keep walking.’

Led Zeppelin’s musical thievery does not make them less talented or ingenious as musicians. They took others’ material, some of it wholesale, but no one can claim they didn’t make it their own, melding American blues and British folk into a truly strange brew. The Polyphonic video above on their use of others’ music begins with a quote from “poet and famous anti-semite” T.S. Eliot, expressing a sentiment also attributed to Picasso, Faulkner, and Stravinsky:

Immature poets imitate, mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.

As far as copyright goes, Zeppelin didn’t always cross legal lines. But as Jacqui McShee said when Page reworked a composition by her Pentangle bandmate, Bert Jansch, “It’s a very rude thing to do. Pinch somebody else’s thing and credit it to yourself.” Maybe so. Still, nobody ever won any awards for politeness in rock and roll, most especially the band that helped invent the sound of heavy metal. See a scoreboard showing the number of originals, credited covers and uncredited thefts on the band’s first four albums here.

Related Content:

Zeppelin Took My Blues Away: An Illustrated History of Zeppelin’s “Copyright Indiscretions”

When Led Zeppelin Reunited and Crashed and Burned at Live Aid (1985)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2111.17 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2329 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment