A Sense of Doubt blog post #3194 - The Great Michigan Pizza Funeral

Pizza is amazing.

RIP the Great Michigan Pizza Funeral.

https://reason.com/2023/02/09/remembering-the-great-pizza-funeral-of-1973/

Fifty years ago this March, dozens of people gathered in Ossineke, Michigan, for one of the strangest funerals in American history. They were there to witness the burial of nearly 30,000 frozen pizzas that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had deemed inedible. The pizzas actually were just fine.

At the center of the "Great Pizza Funeral" was Mario Fabbrini, an Italian immigrant who founded Papa Fabbrini Pizzas after settling in Michigan. In February 1973, Fabbrini heard from officials at the FDA, which was issuing a widespread recall of canned mushrooms after a suspected outbreak of botulism at a canning facility in Ohio. Fabbrini submitted samples of his pizzas to the FDA for testing. When two mice died after eating his pizza samples, Fabbrini was ordered to recall thousands of pies.

The "funeral" on March 5, 1973, was how Fabbrini disposed of the potentially tainted pizzas. Trucks dumped the pies into a massive ditch at a Michigan farm. It was partly a cheesy public relations stunt. The Associated Press covered it, and the funeral made the front page of the Detroit Free Press. It was also a public show of accountability during a botulism scare: Better to lose 30,000 pizzas than to lose customers for years to come.

The funeral might have seemed like a jab at the FDA for mandating the recall in the first place. In the weeks leading up to the funeral, as Fabbrini was rounding up thousands of mushroom-topped pizzas from stores and homes across Michigan, the FDA realized it had made a mistake. The lab mice that had been fed Fabbrini's pizza died of an unrelated infection, not from botulism.

"I think it was indigestion," Fabbrini quipped to an A.P. reporter on the day of the funeral. "Maybe they just didn't like my pizzas."

But having already gone ahead with the recall, Fabbrini was left with little choice but to destroy the pizzas. Hence the funeral, where he cooked other pizzas for hundreds of people, including then-Gov. William Milliken, who came out to witness the weird moment. After the pizzas were buried and the governor said a few words over the grave, Fabbrini reportedly marked the tomb with a garland of red gladioli and white carnations—the colors of pizza sauce and mozzarella cheese.

According to the A.P., a reporter asked Fabbrini about the safety of the pizza he was serving. "Gov. Milliken ate a piece," he replied, "and he's still alive."

The recalled and destroyed pizzas cost Fabbrini $60,000 in lost retail sales, according to a lawsuit that he subsequently filed against his mushroom suppliers. United Canning, the main defendant in the lawsuit, used the fact that the FDA had screwed up the initial diagnosis to argue that Fabbrini had never demonstrated any defect in their products and had voluntarily recalled his pizzas.

The recall, of course, was voluntary in name only. As the Michigan Appeals Court pointed out in its final ruling in the case, "FDA representatives threatened to inform Fabbrini's customers to put the pizzas aside" and "radio stations were advising the public" that Papa Fabbrini Pizzas were potentially unsafe to eat. Faced with those direct threats to the survival of his business, the court's three-judge panel ruled, Fabbrini had no choice but to recall the pizzas. The judges affirmed the $211,000 settlement that a jury awarded Fabbrini.

The FDA, meanwhile, never had to pay anything. And Fabbrini's once-growing frozen pizza business faded away. He sold the remaining assets in the early 1980s.

Botulism is no joke, and Fabbrini probably was right to quickly recall the pizzas rather than risk causing any real funerals. But 50 years after his pies were buried in the dirt of a Michigan farm, the Great Pizza Funeral serves as a reminder that public health officials' mistakes can come with heavy costs.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/michigan-pizza-funeral

ON MARCH 5, 1973, SEVERAL dozen people headed out to a farm in Ossineke, Michigan, to witness an unusual event: the burial of an estimated 30,000 frozen, family-size mushroom pizzas. The mood was somber, and a little cheesy. The governor of Michigan, William G. Milliken, gave a brief homily “on courage in the face of tragedy,” before bulldozers began shoving pizzas into an 18-foot hole.

“I guess by next fall there won’t be anything but the cellophane,” the farm’s owner, Gary Johnson, was quoted as saying as he peered into the mass grave. Pile after pile of pies slid out of a line of pickup trucks and into their final resting place. When it was all over, the victims’ creator, the frozen pizza magnate Mario Fabbrini, laid a two-colored flower garland on the grave: red gladioli for sauce, white carnations for cheese. He then offered slices to all of his guests.The story of the Great Michigan Pizza Funeral is one of loss, terrible maladies, and spilled marinara. But it’s also a classic tale of the strange obstacles immigrants can often face in new countries. In this specific case, it was bad mushrooms that interrupted Fabbrini’s American dream.

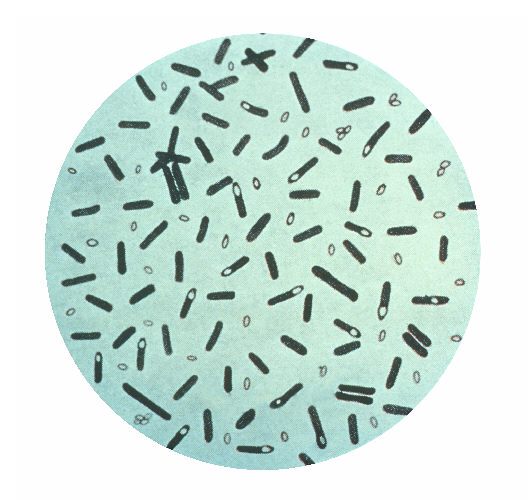

In January of 1973, employees at United Canning in Ohio were checking their inventory when they noticed some of their tins of mushrooms had swelled up. Swelled cans are bad news, and sure enough, tests revealed that the cans were harboring Clostridium botulinum, the bacterium that causes botulism, which can lead to body-wide muscle weakness, low blood pressure, and, sometimes, death.

The FDA removed the affected products from store shelves, but to ensure a comprehensive recall, they had to make some calls up the supply chain. Various prepared food businesses used United Canning’s mushrooms, including Mario Fabbrini, owner of Papa Fabbrini’s Frozen Pizzas.

When Fabbrini got the call, “everything [went] dark,” he later told the Detroit Free Press. Fabbrini was an immigrant, and the architect of his very own all-American success story. He had a visceral understanding of what he stood to lose, and a palpable fear of losing it. He had come to Michigan from Fiume, Italy, after World War II, having grown up under the Fascist regime—“They put the black shirt on me when I was six years old,” he told United Press International. After he got to the U.S., he and his wife, Olga, adapted his family pizza recipe for American palates (“the pizza from my country no one here would eat,” he told one reporter), and went from rolling dough to raking it in.

When he got the news about the mushrooms, Fabbrini stopped his shipments and submitted his mushroom pizzas to a crude contamination test: slices were fed to a couple of FDA lab mice, who promptly died. So Fabbrini recalled his ‘shroom-topped pies, rounding them up from local restaurants and grocery stores. In order to get rid of them, he decided to throw a funeral—partly for the grand optics, but, one suspects, partly as a display of accountability, too.

By the time of the botulism scare, Fabbrini was a decade into his pizza-making career. He was churning out tens of thousands of pies per week, with the help of 22 full-time employees and a state-of-the-art factory. The scandal threatened to undo all he had worked for. “All I could think was, ‘Oh my God. Not me,’” he told UPI.

Some people—at least 17, UPI reported—tried to make Fabbrini’s nightmare come true, claiming they had taken ill from tainted toppings. His neighbors, though, rallied in support. One local fan, anticipating Fabbrini’s bankruptcy fears, offered to put some stock up for collateral if it became necessary to save his business. A bank teller told Fabbrini that a nearby priest was leading prayers for him.

Besides the governor, dozens of community leaders attended the funeral, including Chamber of Commerce members and bank presidents. “It sorta makes you goose pimples about America,” Fabbrini said to the UPI reporter. Governor Milliken later called Fabbrini “an example for all of us.” The article’s subhead, mincing no words, was “Immigrant Offered Help.”

In the end though, Fabbrini’s dramatic action was all for naught. In the two weeks between the recall and the funeral, the pizzas were let off the hook: Their mushrooms were untainted after all. The mice that died after eating them had apparently succumbed not to botulism, but to some other mouse malady. (“I think it was indigestion,” Fabbrini told the Associated Press. “Maybe they didn’t like my pizza.”)

Fabbrini’s sales took a bit of a dive—the pies buried at the funeral cost him about $30,000. According to legal documents, he lost even more money bringing new flavors to market, because his customers lost trust in mushrooms. But his business survived, and the tale of the Great Michigan Pizza Funeral harbors one final twist. Those legal documents only exist because, a few days before the burial, Fabbrini sued the canning company for a million dollars, and won a good chunk of it—an all-American ending to an all-American story.

This story was updated, with minor edits, on October 21, 2020.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2311.16 - 10:10

- Days ago = 3058 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment