A Sense of Doubt blog post #1993 - The Death of Superman and more from 1993 - COMIC BOOK SUNDAY 2008.02

Welcome to Comic Book Sunday, in which I examine 1993, as both the main feature of the post and part of my THE YEAR IN NUMBER category.

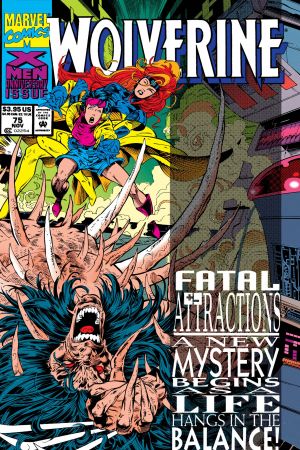

Tired from writing and composing through a complex system of shared content the Saturday Weekly Hodge Podge, also known as Sense of Doubt post #1992, I decided to collect and share the comic books of 1993 in this post today. And guess what? It was a fairly significant year for comics, starting in January with Superman #75, the continuation of the DEATH OF SUPERMAN saga that had started in November of 1992.

Superman was the first major comic book character to be killed, if you do not count as "major' the second Robin (Jason Todd) murdered by the Joker in 1989.

DC also issued black arm bands with the bagged comic that mirrored the adornments worn by characters in the story at the passing of Earth's greatest hero.

from - https://dc.fandom.com/wiki/Death_and_Return_of_Superman

The Death of Superman took place months before the breaking of Batman's back in the "Knightfall" storyline. Some critics praised DC for boldly and innovatively drawing in more readers. However, others were critical, citing the two concurrent storylines as publicity stunts, since it was unlikely that DC would ever eliminate its most popular characters. Some years later, Chuck Rozanksi, owner of retailer Mile High Comics, would pen a controversial essay in the Comics Buyer's Guide which blamed the Death of Superman promotion for playing a significant role in the collapse of the comic book industry in the late 1990s.

Initially, the Death of Superman storyline was a huge success - comic-book fans that had never previously read a Superman title snatched up the issue en masse. When Superman was subsequently revived, however, the backlash was equally strong - diehard Superman fans had bought the Death issue on the expectation that that the book itself would become a prized collectible, and felt 'cheated' when he was suddenly revived (which made the book nearly worthless as a collectible).

also from - https://dc.fandom.com/wiki/Death_and_Return_of_Superman

Reign of the Supermen!

Reign of the Supermen!Following a three month hiatus on the Superman titles, all of them were relaunched. Four new heroes emerged in Superman's place, one in each title, each claiming in some way to be Superman. The story of Adventures of Superman #500 followed Jonathan Kent into the Afterlife. In a possible hallucination, he convinced Superman's soul to come back with him to the living. The only "evidence" that this was not a hallucination was the fact that shortly after Jonathan was revived, four individuals arrived in Metropolis claiming to be Superman. This storyline was known as Reign of the Supermen!

Each of the Supermen were designed with ideas taken from some of the monikers that Superman is often associated with. The four new heroes were:

- The Man of Steel: John Henry Irons was an ironworker and ex-weapons designer for the military who wears a suit of armor and wields a hammer. He did not claim to actually be Superman, but rather to represent the spirit of Superman and continue his legacy. The Man of Steel appeared in Superman: The Man of Steel starting with #22. He later changed his name to just "Steel".

- The Man of Tomorrow, also called the Cyborg Superman, arrived with augmented Kryptonian technology. He was scientifically proven to be Superman but claims amnesia in explanation to his part-mechanical nature. The Cyborg Superman appeared in Superman starting with #78. He later became a major supervillain.

- The Metropolis Kid, who hated being called Superboy, is a reckless teenage clone of Superman. This Superman appeared in the The Adventures of Superman starting with #501. He is a result of the brief time Cadmus attempted to clone Superman. He later had a career as Superboy.

- The Last Son of Krypton was a visored, energy-powered alien who dealt with criminals lethally. The Last Son of Krypton appeared in Action Comics starting with #687. He claims to have the memories of the original Superman, but his emotional distance makes Lois uncertain. He later became the Eradicator.

The first issue for each of the new heroes featured a cardstock cover and a poster of the new hero.

The first half of the Reign of the Supermen! story focuses on each of the Supermen "resuming" his duty as protector of Metropolis and gaining acceptance from the public. Of the four, the reader very quickly learns that neither the cloned Metropolis Kid nor the John Henry Irons Man of Steel are the real Superman. The Cyborg Man of Tomorrow and the Last Son of Krypton were easily bought in by the people as the possible real Superman, since Lois questioned both of them, and both recalled memories which Clark Kent had. Cyborg was even tested by Dr. Hamilton who stated that the Cyborg appeared to be the real Superman.

In actuality, the Last Son of Krypton stole Superman's body and put it in a regeneration matrix in the Fortress of Solitude, drawing on his recovering energies to power himself, as bright light blinded him. It is revealed that the Last Son is the Eradicator, an ancient Kryptonian weapon, and the Cyborg is the deranged consciousness of Hank Henshaw, which used Superman's birthing matrix to create a physical duplicate of his body.

In actuality, the Last Son of Krypton stole Superman's body and put it in a regeneration matrix in the Fortress of Solitude, drawing on his recovering energies to power himself, as bright light blinded him. It is revealed that the Last Son is the Eradicator, an ancient Kryptonian weapon, and the Cyborg is the deranged consciousness of Hank Henshaw, which used Superman's birthing matrix to create a physical duplicate of his body.The regeneration matrix broke open, and the original Superman emerged, greatly depowered, but alive. Meanwhile, the Cyborg helped Mongul destroy Coast City, believing he killed the Last Son in the explosion, and captured Superboy, holding him in Engine City, a towering construct erected where Coast City once stood. Superboy escaped and flew back to Metropolis to get the Man of Steel to help him fight the Cyborg. Before he could tell the whole story, however, an overbearing Kryptonian Battlesuit rose out of the harbor, and the two heroes attacked it.

After suffering heavy damage, the suit opened, revealing a still-weak Superman, who had used it to walk all the way back from the Fortress of Solitude. Despite his weakened state, he quickly joined the other Supermen in defending Coast City. Upon his revelation, he acknowledged himself as the real Superman (the fifth person at this point to claim that title). When asked by Lois Lane what made him any different from the other Supermen, he responded with "How about... To Kill A Mockingbird?" (Clark Kent's favorite movie, and something he shared with only those closest to him). Though she remained hesitant, Lois mentally acknowledged that this was something only the real Clark Kent would know.

During the battle of Coast City, the Cyborg launched a devastating missile at Metropolis, with the intent of destroying it and putting a second Engine City in its place. Superboy managed to grab onto the missile as it launched, riding it all the way to Metropolis, which he narrowly saved from destruction.

Green Lantern Hal Jordan had returned from space to find his hometown destroyed. He immediately attacked Engine City and fought Mongul, shattering the Man of Steel's hammer across his face. Meanwhile, the Last Son/Eradicator joined the fight after recovering in the Fortress, and blocked the Cyborg from dousing Superman with lethal Kryptonite gas. The gas interacted with the Eradicator as it passed through and into Superman, returning his powers rather than killing him. The Eradicator's body degenerated into a lifeless husk, and the Cyborg looked for Superman's body in the debris and Kryptonite mist. Superman blindsided him with an attack using his super-strength, and he punched a hole right through the Cyborg. He destroyed his body, but his consciousness survived. Supergirl used the remnants of the black Kryptonian suit to re-create Superman's traditional costume, and the group returned to Metropolis.

Again, like the previous two storylines, the collected edition of Reign of the Supermen! did not use its original title, DC Comics instead chose to use The Return of Superman.

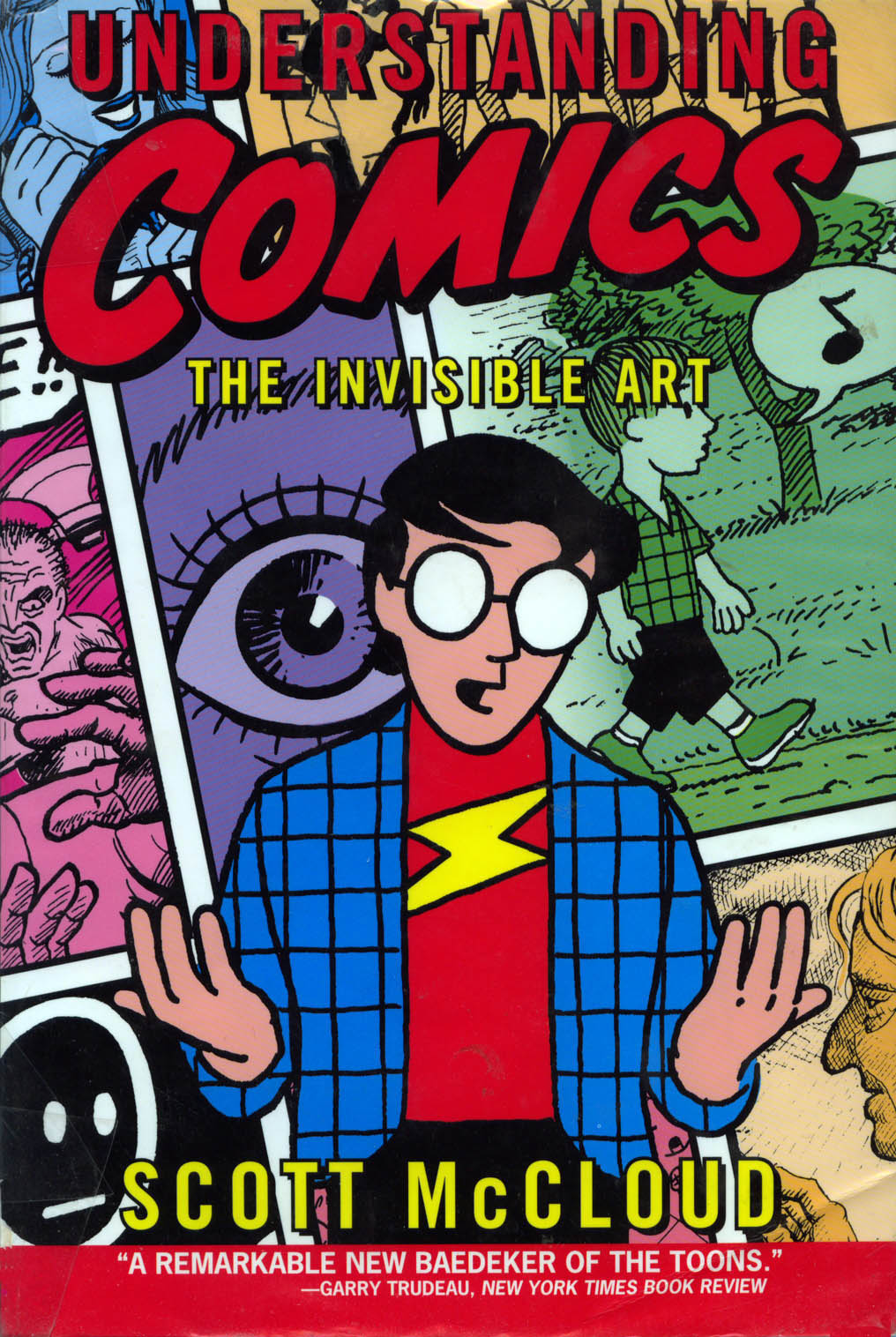

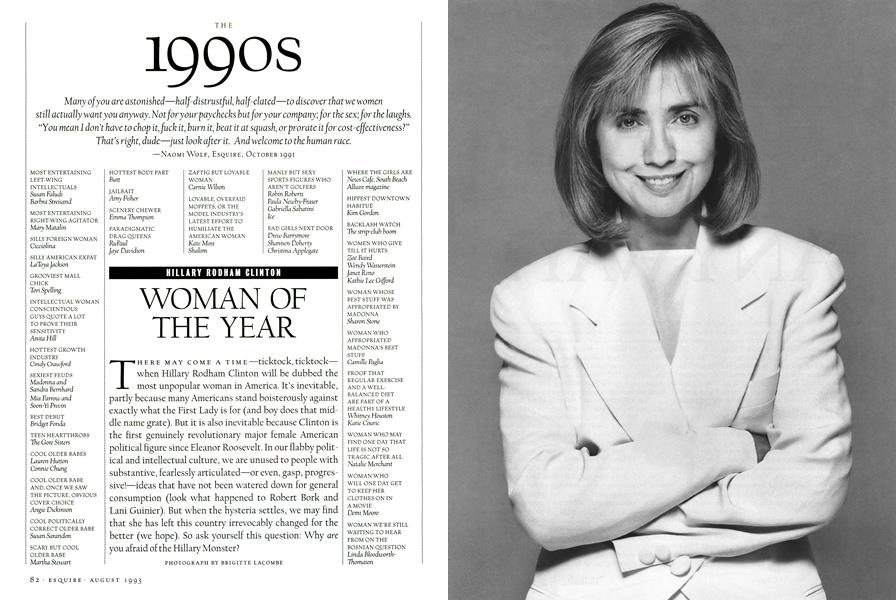

1993 was the year of the publication of one of the most important books in all of comics history:

UNDERSTANDING COMICS by Scott McCloud.

Top 50 DC Comics Of 1993

Top 50 Marvel Comics Of 1993

Apparently, some felt that the comic industry CRASHED in 1993.

https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standard/the-crash-of-1993

The Crash of 1993

What Tolstoy wrote about families is true of economics: Boom times are all alike, but every crash is disastrous in its own way. That’s why stories about bursting bubbles are always instructive. There are lessons in the smallest of them, even the bubble that led to the comic book crash of 1993.

Once upon a time comic books were ubiquitous and worthless. Sold in drugstores for a dime during the 1930s and ’40s, they were fun, pulpy reading for kids and youths. Issues were printed by the hundreds of thousands—even a million for the top titles—and then read, passed around in classrooms, locker rooms, and barracks, and eventually thrown away. A few odd ducks collected the things for pleasure, but this barely amounted to so much as a hobby.

Over the years the appeal of comics narrowed somewhat, but the audience grew more intense as it shrank. Specialty shops appeared that sold nothing but comic books. By the mid-1980s, a brisk collectors’ market existed.

In 1974 you could buy an average copy of Action Comics #1—the first appearance of Superman—for about $400. By 1984, that comic cost about $5,000. This was real money, and by the end of the decade, comics sales at auction houses such as Christie’s or Sotheby’s were so impressive that the New York Times would take note when, for instance, Detective Comics #27—the first appearance of Batman—sold for a record-breaking $55,000 in December 1991. The Times was there again a few months later, when a copy of Action Comics #1 shattered that record, selling for $82,500. Comic books were as hot as a market could be. At the investment level, high-value comics were appreciating at a fantastic rate. At the retail level, comic-book stores were popping up all across the country to meet a burgeoning demand. As a result, even comics of recent vintage saw giant price gains. A comic that sold initially for 60 cents could often fetch a 1,000 percent return on the investment just a few months later.

But 1992 was the height of the comic-book bubble. Within two years, the entire industry was in danger of going belly up. The business’s biggest player, Marvel, faced bankruptcy. Even the value of blue chips, like Action Comics #1 and Detective Comics #27, plunged. The resulting carnage devastated the lives of thousands of adolescent boys. I know. As a 12-year-old I had a collection worth around $5,000. By the time I was ready to sell my comic books to buy a car—such are the long-term financial plans of teenagers—they were worthless.

The comic-book bubble was the result not of a single mania, but of a confluence of events. Speculation was part of the story. Price gains for the high-value comics throughout the 1980s attracted speculators, who pushed the prices up further. At the retail level, the possibility that each new issue might someday sell for thousands of dollars drove both the sale of new comics and the market for back-issue comics. It was not uncommon for a comic book to sell at its cover price (generally 60 cents or $1) the month it was released and then appreciate to $10 or $15 a few months later.

But the principal cause of the bubble was the industry’s distribution system. Comic books are created and released by publishing houses. There are two giants (Marvel and DC) and then a raft of much smaller independents, which come and go with great frequency. All of the publishing houses left the task of physically getting comics from the printing presses to the retailers to a group of middlemen—the distribution companies.

These distribution companies determined who could and couldn’t sell comic books. They imposed requirements on retailers, demanding that they demonstrate financial reserves and guarantee certain numbers of orders each month. The reason comics were so slow to migrate from newsstands and five-and-dimes to dedicated comic book shops (a process that took nearly 50 years) is that it was hard for these small start-ups to muster the resources needed to secure distribution. These hurdles are why, in 1979, there were only about 800 comic-book shops in the entire world.

In the 1980s, two of the larger distribution companies—Diamond and Capital City—began an aggressive course of expansion. They wanted to nationalize their businesses and eliminate smaller, regional competitors. Their strategy was to lower the barrier to entry for prospective retailers.

Diamond and Capital City were happy to sign distribution agreements with just about anyone. As Chuck Rozanski, the owner of the country’s largest comic-book retailer, Mile High Comics, explained a few years back in a brilliant series of essays about the comic-book bubble, Diamond and Capital City were ready to set up an account for anyone with an initial order check of $300. This aggressive stance had the practical effect of turning many collectors into dealers. Comic book shops proliferated, growing from 800 in 1979 to 10,000 by 1993. Diamond and Capital City were so successful that they drove every other distributor in America out of business.

With all of these comics shops sprouting across suburban America, the two remaining distributors took in record numbers of orders every month. Seeing these orders, the publishers thought they were presiding over a massive boom. So they upped their prices and began publishing more titles, adjusting the supply to meet what they thought was demand. In 1985 Marvel published 40 titles a month, and each book cost 60 cents. By 1988 they were putting out 50 titles for $1 apiece. By 1993, they were offering 140 books a month, selling for $1.25 and up.

All the while, the distributors kept standing up new retailers, who kept putting in orders, enticing the publishers to produce ever more books. It was an unsustainable loop, but what made the situation particularly perilous was that in the comic-book business, orders are placed months in advance and unsold inventory cannot be returned. Retailers eat unsold books as overstock. (Rozanski estimates that at the bubble’s peak, 30 percent of all comics being published wound up as overstock.) In other words, the loop was structured so the publishers would get negative feedback only after the industry had gone over the cliff and the retailers started going belly up.

Which is precisely what happened in 1993. By expanding their output to hundreds of titles, the publishers had diluted the quality of their product to embarrassing levels. That, combined with the higher retail prices, drove away customers.

Many of the new comic-book stores were undercapitalized and poorly run. The weakest of them folded first, and their demise began a cascade: Publishers saw a rapid and dramatic decline in orders, so they moved to reduce costs by cutting back the number of titles they shipped. Which led to less product for the remaining retailers to sell. Which pushed the stores on the margins of survival out of business. The death spiral was on.

By the time the bubble’s soapy residue washed away, nine out of ten comic book shops in America had closed their doors. Publisher sales of new comics dropped by 70 percent. On December 27, 1996, Marvel, the General Motors of comics, filed for bankruptcy. The market for used comics was flooded with the cadaverous inventories of out-of-business stores. The prices of high-value comics dipped or plateaued. Many lower-value comics (books under $100) saw significant declines. Comics printed during the run-up to the bubble became virtually worthless, as the speculator-driven sales combined with the unsold issues to create a massive oversupply.

Since the comics apocalypse, some parts of the market have recovered and even thrived. Over the last ten years, the Golden Age glamour books (such as the early Action and Detective Comics) crept into the six-figure range, and a whole host of books, ranging from Amazing Fantasy #15 (the first appearance of Spider-Man) to Donald Duck Four Color #29, began fetching five-figure sums. As the Great Recession dawned in the fall of 2008, the comics market remained reasonably intact. New issue sales dropped precipitously, but then rebounded. The prices of high-value older issues continued to rise. In one three-day span last year, two comics (an Action #1 and a Detective #27) broke records, selling for $1 million, and then $1.075 million. A month later, an Action #1 went for $1.5 million.

But the contours of the industry have changed almost beyond recognition. In 1950, Marvel and DC together sold roughly 13 million comic books a month. In 1968, they put out 16 million a month. Since 1993 the overall sales trend has been inexorably downward. For January 2010, all American publishers combined sold a total of 5.63 million comics.

This might sound like an industry marching toward oblivion, yet in 2009, Disney paid $4 billion to acquire Marvel (DC was already owned by Time-Warner). The reason for this gaudy valuation is that the comic books themselves are no longer important to the comic-book industry. They’re loss leaders. The real money is in the comic-book properties, which power toy and merchandise sales, theme parks, and above all else movie franchises. Since 1997, 26 comic book adaptations have gone on to gross more than $100 million at the box office. Twelve of these grossed more than $200 million. More—many more—are coming soon to a theater near you.

As a financial concern, comic book publishers are no longer in the publishing business: They’re curators of, and incubators for, extremely valuable intellectual property. To comic-book collectors, that’s very good news.

Or rather, it’s very good news for some comic-book collectors. As a boy I had the misfortune to be buying comics in the run-up to the bubble. Almost none of my books ever recovered their value. Sure, Action Comics #1 will fetch you a million plus, but look around on auction websites and you can find sellers offering lots of a thousand Bronze- and Modern-Age comics—the books I was collecting—for $10. They’re worth just a little less than firewood.

As painful as it was for some of us, the comic-book bubble teaches two important lessons. First, bubble-mania is not always the fault of buyers and sellers. Sometimes it’s caused by intermediaries. Second, sometimes markets don’t “come back.” People who owned blue-chip comics took a hit in 1993. People who owned modern-era comics were wiped out, the value of their collections never to return.

The comic-book market resembles today’s housing market in unsettling ways. The substantive differences between houses and comic books are as obvious as they are enormous. Yet in both cases the speculatory bubble was helped along by irresponsible middlemen—the distribution companies in one case and the credit-ratings agencies and mortgage appraisers in the other.

And it’s unclear to what extent the housing sector is going to rebound. We are now officially in a housing double-dip, with prices in most parts of the country below what they were in 2000—and still falling. Discussing the topic several weeks ago, Moody’s economist Celia Chen told reporters that, nationally, house prices might regain their 2006 levels by 2021. In some large states—such as Florida and California—Chen placed the recovery in 2030. What’s terrifying about such predictions isn’t the specific date. It’s that either way, the return of prosperity is so far in the future as to indicate that no one really has any idea when recovery will come. Or if.

Lots of houses are the functional equivalent of blue-chip comic books. Like a copy of Action Comics #1, a co-op in Manhattan, a townhouse in Georgetown, or a bungalow in Santa Monica will eventually regain its previous value and will prove to be an excellent investment in the long run. And the same can probably be said for the majority of suburban homes in established metro areas from Seattle to Atlanta.

But during the run-up to the housing crash, a crush of construction appeared in places like the Carolina coasts, the southwestern desert, and pockets of Florida. In the summer of 2009, the Associated Press ran a story on Victor Vangelakos, who bought a condominium unit in a new 32-story waterfront building in Fort Myers. He’s the only person in the building—every other unit was either foreclosed on or never sold. That’s not quite as bad as things are in Spain, where entire towns sit vacant. In Yebes, an hour from Madrid, hundreds of rowhouses sit empty on brand new streets. Almost none of them was ever sold. Yebes is a ghost town now, unlikely ever to “come back.”

I have a comic book like that. In 1984, DC launched what became an immensely popular series, The New Teen Titans. The first issue carried a premium cover price of $1.25, the result of the series being printed not on the usual newsprint but on higher quality “Baxter” paper. I missed the first issue when it debuted, and the back-issue price quickly climbed. In a few months I saved up the scratch to buy a copy.

I paid $25, a not-inconsiderable sum for a 10-year-old. It was the jewel of my collection. Today you can buy a copy in near-mint condition for $1.50.

| from issue #2 |

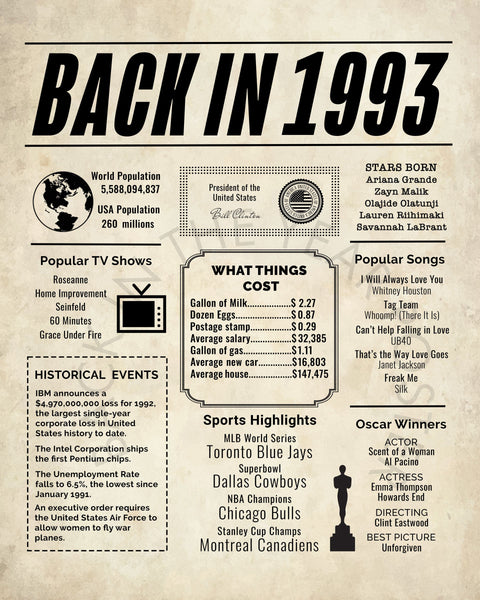

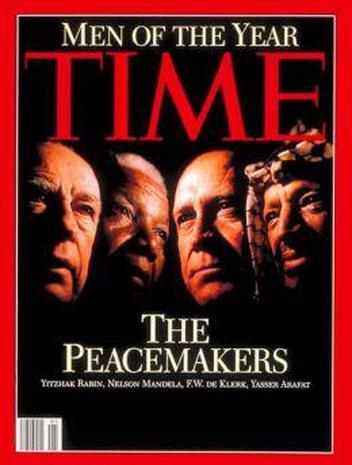

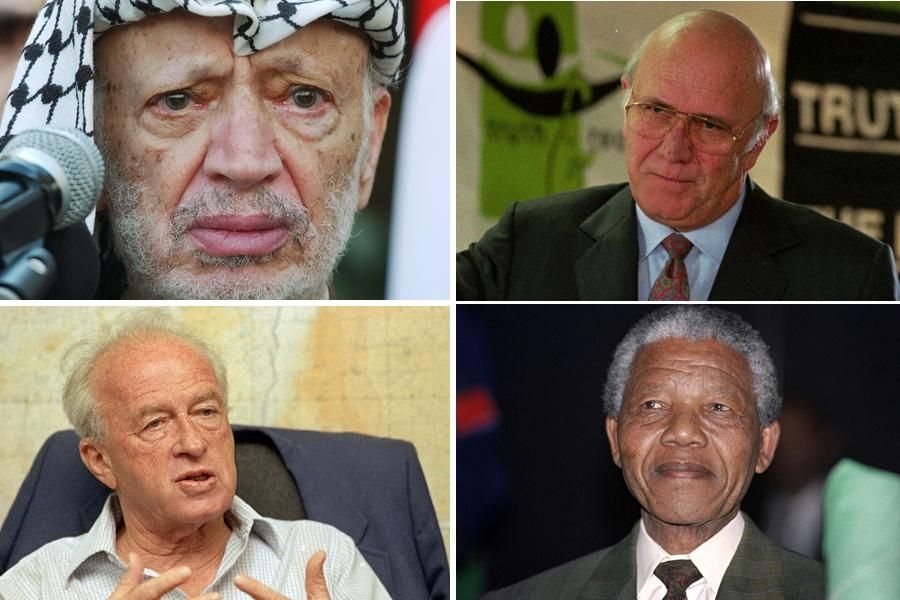

THE YEAR IN NUMBER 1993

In 1993, like 1992, I was in between major things. I would return to Western Michigan University to teach technical writing after being away for two years since my graduate program appointment ended. It would be another two years before I was back to teaching in the English department.

I stayed busy involved in minor relationships. I was working at the video store and teaching for three schools. According to my poetry journal, which was slowly being something that I did not write in too much, 1993 was the year I developed a huge crush on a young woman named Ruth, who later would come out as gay but who at the time was still under the thumb of her fundamentally religious family. She was a poet, very smart, and absolutely gorgeous. She stole my heart while I was seeing another woman (Julie S) who had not stolen my heart. I wrote some love poems for Ruth in late July and early August of that year.

It would be another two years before I would enter into another of what I consider to be the top

I think I took one of my trips to New York in that year because was writing a lot of fan fiction for TITANTALK; however, I was phasing out this work.

I was finishing the Star Trek novel that would become my MFA project. If I had the filing cabinets that are back in Michigan, I would be able to verify when we finished, when we secured an agent, and some other things I cannot determine from my ill-used journal.

Also, I can see that in April I attended the Magritte exhibit in Chicago, a show that was a huge inspiration, and one I would visit three or four times, once spending many hours taking notes, which are housed in my journal. I remember being at that show one of those times with Amanda S, with whom I was also having an on and off again thing, which was one again when she and I joined my sister and some guy for a Michigan football game and then later watched the final game of the world series as the Blue Jays beat the Phillies.

I had what may be my best short story "600 Cows" accepted for publication in an anthology of Michigan writers and edited by smart folks at the Michigan Quarterly Review.

The problem with reconstructing these lost years is the lack of points of reference, especially photos.

1993 For the first time Islamic Fundamentalists bomb World Trade Center. A devastating tsunami, caused by an earthquake off Hokkaido, Japan kills 202 on the small island of Okushiri. The ever popular Beanie Babies are launched . In technology the first bagless vacuum cleaner is invented and Intel introduces the Pentium Processor.

1993 WIKI

In 1993, I drove with my friend Jack Lee to Vermont to visit our friend Tom and his new wife Caroline. Our return was delayed by one of the biggest blizzards of the century. I have a picture of shoveling out the six feet of snow plus drifting that buried my new car, the GEO Metro, but I can only find this picture, which I think is from the same trip.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2008.02 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1857 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment