A Sense of Doubt blog post #2180 - Why Impeaching a Former President is Necessary

This is a short read, and it makes the point clearly that it IS CONSITUTIONAL to impeach a president once out of office, that he must be held accountable for one of the most heinous and TREASONOUS things ever done by a public servant let alone a president, and that there should be some real consequences, such as at the very least, ensuring that Trump can never again run for any public office.If there is any justice that Trump will be held to account. Indicted. Sentenced. At the very least imprisoned. And if not indicted and punished, then at least censured so he can never run for office ever again.

And after that is done, all the other gutless "public servants" who have done his bidding, kissed his ring, served him, supported his lies, enabled this insurrection, those people have to be held to account, also.

NEVER FORGET.

https://theconversation.com/impeaching-a-former-president-4-essential-reads-153821

Impeaching a former president – 4 essential reads

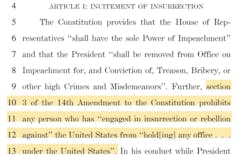

As the U.S. Senate takes up the second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump, there are a lot of questions about the process and legitimacy of trying someone who is no longer in office, including what the point is and how impeachment works. The House has passed an article of impeachment, charging him with “incitement of insurrection” in connection with the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, and now the process turns to the Senate.

The Conversation has published several articles from scholars explaining aspects of the situation, as well as describing more generally what the purpose of impeachment was for the founders when they wrote the Constitution. This is a selection of excerpts from those articles.

1. Does it matter that Trump is out of office?

The previous three impeachment trials of presidents – of Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998 and Trump himself, the first time, in early 2020 – were conducted while the accused were still in office. Some Republicans have questioned whether it’s even constitutional to conduct an impeachment trial of a former president.

But Michael Blake, a political philosopher at the University of Washington, explains that trying him is useful morally and politically, setting a boundary around the powers of the presidency, even if Trump can no longer be expelled from office:

“The impeachment of President Trump is an indication that there is a need to mark out, through a definitive statement, what no president ought to do. It will also set the moral limits of the presidency – and, thereby, send a message to future presidents.”

2. What happens if Trump is convicted?

Though Trump can no longer be removed from office, he may still face consequences. Kirsten Carlson, a law professor at Wayne State University, explains that there is an additional step:

“The Senate also has the power to disqualify a public official from holding public office in the future. If the person is convicted …, only then can senators vote on whether to permanently disqualify that person from ever again holding federal office. … A simple majority vote is all that’s required then.”

3. What if he is not convicted?

It is possible that two-thirds of the senators may not vote to convict Trump. But there is another way Congress might seek to bar Trump from holding office in the future.

Gerard Magliocca, a law professor at IUPUI, describes that approach, which would use Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. He writes that the amendment, created after the Civil War, bars people “from serving in a variety of government offices if they ‘shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion’ against the United States Constitution.”

However, it’s not enough for a majority of Congress to vote to declare Trump is ineligible to serve in office again, Magliocci explains: “only the courts, interpreting Section 3 for themselves, can bar someone from running for president.”

4. What is the real purpose of impeachment?

Even if immediate consequences are uncertain, the founders still understood that impeachment sent a powerful message, writes Clark Cunningham, a legal scholar at Georgia State University.

Based on his research into the people who wrote the Constitution and the statements they made at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Cunningham explains that “the founders viewed impeachment as a regular practice with three purposes:

- To provide a fair and reliable method to resolve suspicions about misconduct;

- To remind both the country and the president that he is not above the law;

- To deter abuses of power.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

https://theconversation.com/trump-impeachment-trial-decades-of-research-show-language-can-incite-violence-154615

Trump impeachment trial: Decades of research show language can incite violence

Senators, acting in the impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump that begins on Feb. 9, will soon have to decide whether to convict the former president for inciting a deadly, violent insurrection at the Capitol building on Jan. 6.

A majority of House members, including 10 Republicans, took the first step in the two-step impeachment process in January. They voted to impeach Trump, for “incitement of insurrection.” Their resolution states that he “willfully made statements that, in context, encourage – and foreseeably resulted in – lawless action at the Capitol, such as: ‘if you don’t fight like hell you’re not going to have a country anymore.’”

Impeachment proceedings that consider incitement to insurrection are rare in American history. Yet dozens of legislators – including some Republicans – say that Trump’s actions leading up to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol contributed to an attempted insurrection against American democracy itself.

Such claims against Trump are complicated. Rather than wage direct war against sitting U.S. representatives, Trump is accused of using language to motivate others to do so. Some have countered that the connection between President Trump’s words and the violence of Jan. 6 is too tenuous, too abstract, too indirect to be considered viable.

However, decades of research on social influence, persuasion and psychology show that the messages that people encounter heavily influence their decisions to engage in certain behaviors.

How it works

The research shows that the messages people consume affect their behaviors in three ways.

First, when a person encounters a message that advocates a behavior, that person is likely to believe that the behavior will have positive results. This is particularly true if the speaker of that message is liked or trusted by the target of the message.

Second, when these messages communicate positive beliefs or attitudes about a behavior – as when our friends told us that smoking was “cool” when we were teenagers – message targets come to believe that those they care about would approve of their engaging in the behavior or would engage in the behavior themselves.

Finally, when those messages contain language that highlights the target’s ability to perform a behavior, as when a president tells raucous supporters that they have the power to overturn an election, they develop the belief that they can actually carry out that behavior.

Consider something we have all encountered in a more lighthearted context – messages designed to motivate exercise. These messages often tell us one (or more) of three things. They tell us that exercise will lead to positive outcomes – “You will get physically fit!” They tell us that others exercise or would approve of our taking part in exercise – “Work out with a friend!” And they tell us that it is within our power to begin an exercise program – “Anybody can do it!”

In this context, these messages are likely to increase the message target’s likelihood of exercising.

Unfortunately, as we saw on Jan. 6, these principles of persuasion apply to less benign behaviors as well.

How Trump did it

Now let us return to what happened in Washington on Jan. 6.

Even in the weeks before the election, Trump’s rhetoric was belligerent. His campaign solicited supporters to “enlist” in the “Army for Trump” to help reelect him. Following the election and in the lead-up to the attack on the Capitol, President Trump made repeated false claims of election fraud, arguing that something needed to be done to remedy the alleged fraud. His language often took an aggressive tone, suggesting that his supporters must “fight” to preserve the integrity of the election.

By inundating his supporters with these lies, Trump made two key beliefs acceptable to his followers. First, that aggression against those accused of trying to undermine his “victory” is an acceptable and useful means of political action. Second, that aggressive, possibly violent attitudes against Trump’s political adversaries are common among all his supporters.

Words have consequences

In the weeks following the election, allies of President Trump, including Rudy Giuliani, Republican U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz, GOP Sens. Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley and others, only reinforced these beliefs among Trump supporters by perpetuating his lies.

With these beliefs and attitudes in place, Trump’s Jan. 6 speech outside the White House served as a key accelerant to the attack by sparking the raucous crowd to action.

In his pre-attack speech, Trump said that he and his followers should “fight like hell” against “bad people.” He said that they would “walk down Pennsylvania Avenue” to give Republican legislators the boldness they need to “take back the country.” He said that “this is a time for strength” and that the crowd was beholden to “very different rules” than would normally be called for.

Less than two hours after these words were spoken, violent insurrectionists and domestic terrorists breached the Capitol.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

In the case of Donald Trump, the relationship between words and actions never seems clear. But make no mistake, there is a scientifically valid case for incitement.

Decades of research have demonstrated that language affects our behaviors – words have consequences. And when those words champion aggression, make violence acceptable and embolden audiences to action, incidents like the insurrection at the Capitol are the result.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 12, 2021.![]()

Kurt Braddock, Assistant Professor of Public Communication, American University School of Communication

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2102.05 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2044 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment