A Sense of Doubt blog post #2177 - Radium Age (Proto) Science Fiction

Just a share. I am behind and ill.

I did a related post not too long ago:

A Sense of Doubt blog post #2112 - Science Wonder Stories - Hugo Gernsbackhttps://www.hilobrow.com/radium-age-100/

RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI: 100 BEST

Back in 2008, Annalee Newitz and Charlie Jane Anders invited me to write for io9.com about a topic they knew I had recently become fascinated with: proto-sf novels published after the emerging genre’s 1864–1903 Scientific Romance era, but before its (1934–63) so-called Golden Age. The 1904–33 era is one in which sf fans and historians have never been particularly interested. At first, I called this neglected period the Pre-Golden Age, but later I coined the phrase Radium Age — a moniker which I’ve popularized by writing about the era for the scientific journal Nature, Boing Boing, and elsewhere; and by reissuing 10 science fiction novels from that period under HiLoBooks’s purpose-built Radium Age Science Fiction imprint.

At io9, I published a short series of semi-exhaustive posts on the following topics: Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912.

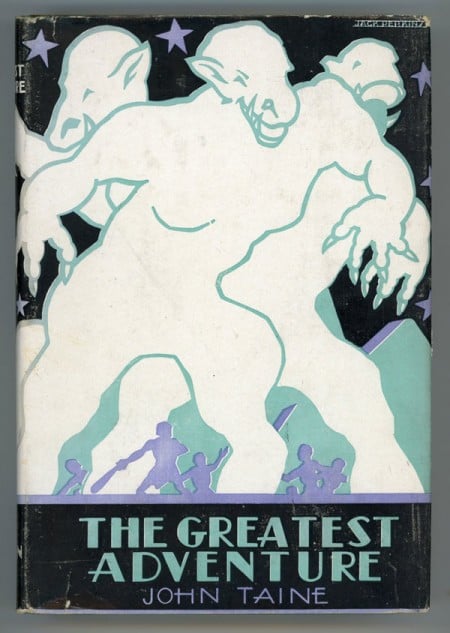

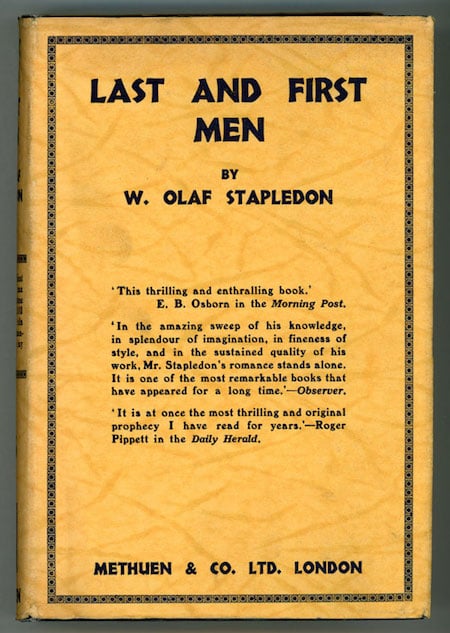

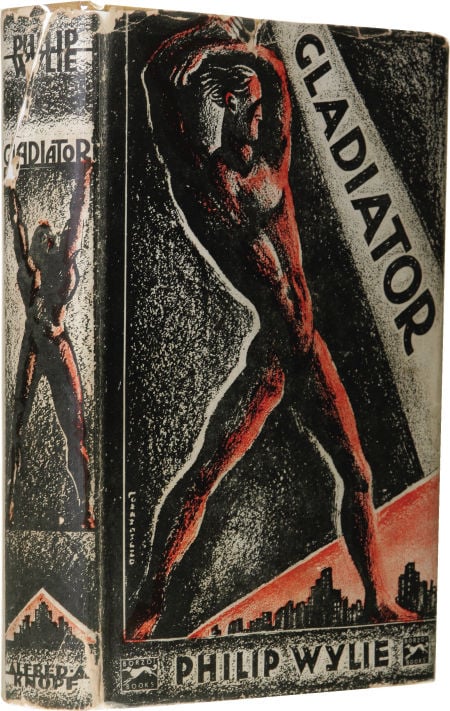

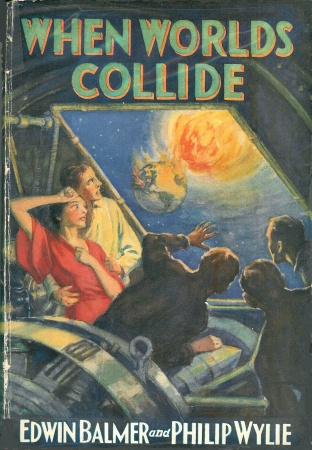

I took notes for subsequent posts on, e.g., Air Battles, Antigravity, Interplanetary Voyages, Lost Worlds, Mad Scientists, Time Travel, and Utopias. I collected a roomful of books by Olaf Stapledon, William Hope Hodgson, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, Karel Čapek, Hugo Gernsback, E.E. “Doc” Smith, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, David Lindsay, John Taine, Jack Williamson, S. Fowler Wright, Gustave Le Rouge, A. Merritt, Murray Leinster, Jean de La Hire, Maurice Renard, Philip Wylie, Aldous Huxley, and many less well-known science fiction authors from the time. And then I moved onto a wide variety of other commercial and artistic projects, which you can read about here.

Before packing up my RA books, in 2015–2016 I assembled the following list of the 100 Radium Age proto-sf novels that (so far) I’ve most enjoyed discovering. Please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2016)

SUMMER 2020 UPDATE: I’ve signed up to edit a RADIUM AGE series for The MIT Press. We’ll begin publishing in 2022. The Radium Age: Emergence of Science Fiction book series is dedicated to reissuing influential but overlooked proto-sf novels and stories published during the first three and half decades of the twentieth century — an era which bequeathed us such enduring science-fictional tropes as the telepath, the berserk robot, the tyrannical superman, and the environmental catastrophe. Introductory essays by sf authors, historians, scientists, and other experts will situate these texts within their own social and political context while also drawing out contemporary lessons. The aim of the series is to instruct and inform, while also offering thrills and chills to sf fans.

We’re putting together a dream-team advisory panel to help surface overlooked texts, and strategize about how to add scholarly/readerly value to our reissues via introductions and afterwords. The panel includes:

- Annalee Newitz. Annalee is the author of The Future of Another Timeline, and Autonomous, which won the Lambda Literary Award. Their forthcoming nonfiction book Four Lost Cities is about archaeology. A contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, they are also the co-host of the Hugo Award-winning podcast Our Opinions Are Correct. Previously, they were the founder of io9, and served as the editor-in-chief of Gizmodo.

- Anindita Banerjee. Anindita is an associate professor of Comparative Literature and the chair of humanities in the Environment and Sustainability Program at Cornell University. She works on global science fiction literature and media in several languages. Her latest books are Science Fiction Circuits of the South and East (2018) and South of the Future: Marketing Care and Speculating Life in South Asia and the Americas (2020).

- David M. Higgins. David teaches in the English Department at Inver Hills College in Minnesota, and he is the SF Editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books. His research (which has appeared in a variety of books, journals, and reference volumes) examines science fiction in postwar American culture.

- kara lynch. kara is a time-based artist living in the Bronx, and coeditor of We Travel the Space Ways: Black Imagination, Fragments, and Diffractions (2020). Through low-fi, collective practice and social intervention, lynch explores aesthetic/political relationships between time + space. This artist’s practice is vigilantly raced, classed, and gendered – Black, Queer, and Feminist.

- Ken Liu. Ken is the author of the silkpunk epic fantasy Dandelion Dynasty series, as well as The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories and The Hidden Girl and Other Stories. A former software engineer, corporate lawyer, and litigation consultant, Liu frequently speaks at conferences and universities on a variety of topics such as futurism, cryptocurrency, history of technology, and bookmaking.

- Sean Guynes. Sean is a writer, editor, and SFF critic who lives in Ann Arbor, MI. His shorter writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Strange Horizons, Tor.com, World Literature Today, PopMatters, and elsewhere. He is currently writing a book on Ursula K. Le Guin.

- Sherryl Vint. Sherryl is Professor of Media & Cultural Studies at the University of California, Riverside, where she directs the Speculative Fictions and Cultures of Science program. She is an editor of Science Fiction Studies and has published widely in the field, including most recently Biopolitical Futures in Twenty-First Century Speculative Fiction.

Stay tuned!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

RADIUM AGE SCI-FI: THE OUGHTS (1904–1913)

RADIUM AGE SCI-FI: THE TEENS (1914–1923)

RADIUM AGE SCI-FI: THE TWENTIES (1924–1933)

The following classics from the science fiction genre’s Scientific Romance (1864–1903) era are listed here in order to provide some historical context.

- Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864).

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Vril, the Power of the Coming Race (1871).

- Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872).

- Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888).

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde (1888).

- William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890).

- H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895).

- H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898).

- M.P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud (1901).

The Oughts are a kind of interregnum period between sci-fi’s Scientific Romance era (1864–1903) and the Radium Age. Verne, Wells, Kipling, Arnold, Baum and some others who published science fiction from 1904–1913 are much better known for their earlier novels; and their sensibilities were formed in the late 19th century. (Similarly, the Thirties [1934–1943] are an interregnum between sci-fi’s Radium Age and the so-called Golden Age [1934–63].) Still, by the end of the Oughts — particularly in the annus mirabilis of 1912 — we can discern the Radium Age’s emergence.

For context, see my list of Best Nineteen-Oughts Adventure.

- G.K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904). In an alternative-history version of England (it’s set in 1984), monarchs are selected at random instead of inheriting the title. When Auberon Quin, a man who aspires to live life like a medieval adventure, becomes king, he mandates that each of London’s neighborhoods become an independent state, complete with unique local costumes. Everyone goes along with the conceit until young Adam Wayne, a born military tactician, takes the game too seriously… and becomes the Napoleon of Notting Hill. War rages throughout the city — fought with sword and halberd. Fun fact: Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins is known to have admired The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

- H.G. Wells’s The Food of the Gods (1904). Does The Food of the Gods belong on a list of the 100 Best Radium Age (Proto-)Science Fiction novels? I originally determined that the genre’s pioneering Scientific Romance era ended in 1903 because, after that date, H.G. Wells lost his touch. The First Men in the Moon (1901) is Wells’s last terrific sf novel; The Food of the Gods is his first un-terrific one. However! Un-terrific Wells is still pretty damn good. A chemical intended to make chickens grow larger accidentally causes plants, wasps, earwigs, and rats to grow as well… and it spawns a race of human giants, too, who must struggle to survive. Fun fact: The 1977 Marvel Classics Comics edition of the story is great.

- Jules Verne’s The Master of the World (1904). In this sequel to Verne’s 1886 adventure Robur the Conqueror, FBI(-ish) Chief Inspector Strock arrives in North Carolina to investigate what appears to be an imminent volcanic eruption. Meanwhile, a supercar is spotting traveling at 120 miles per hour; and a speedboat/submarine is glimpsed in the waters off New England. Aha! The brilliant inventor Robur is back, and this time he has invented a ten-meter long multi-purpose vehicle, The Terror. Determined to have it for military purposes, the feds first attempt to buy the machine, then attack Robur. With a captive Strock aboard, Robur escapes in The Terror over Niagara Falls, then challenges God by heading into a Caribbean thunderstorm… at which point his amazing craft is shattered by lightning. Fun fact: Is this one of Verne’s best novels? No! I include it here to demonstrate the context from which Radium Age science fiction emerged. Here we see one of the genre’s pioneers, at the end of his career (and life), questioning man’s ability to use science and technology to benefit humankind.

- Rokeya Sakhawat Hussain’s Sultana’s Dream (1905). Originally published in English in The Indian Ladies Magazine of Madras, Hussain’s short story depicts a peaceful, crime-free utopia in which women run everything and men are secluded — i.e., in a purdah-like system. What’s more, the women use advanced technology that makes possible laborless farming and flying cars; they have solved the problem of solar energy, and control the weather. Most impressively, perhaps: The workday is two hours long, since men used to waste six hours of each day in smoking! Fun fact: One of the first examples of feminist science fiction. The author was a Muslim feminist, writer, and social reformer who lived in British India.

- Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (1905). Kipling’s novella follows the exploits of an intercontinental mail dirigible battling the perfect storm. Between London and Quebec we learn that a planet-wide Aerial Board of Control (A.B.C.) now enforces a technocratic system of command and control not only in the skies but in world affairs. It’s an impressively nuanced portrait of a future in which dirigibles — not airplanes — have triumphed. Kipling goes so far as to include excerpts from the Aerial Board of Control Bulletin, complete with letters to the editor, book reviews, and advertisements. “An amazing tour-de-force of inspired genius,” according to Bruce Sterling. “Kipling, in 1905, is doing things that science fiction as a genre wouldn’t achieve until Robert Heinlein arrived in the late 1940s.” Fun fact: Kipling’s 1912 story “As Easy As A.B.C.” recounts what happens when agitators demand the return of democracy. Both titles have been reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Matthew De Abaitua and an Afterword by Bruce Sterling.

- Edwin Lester Arnold’s Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation (1905). In this satirical, nightmarish, episodic update of Gulliver’s Travels, Lieut. Gullivar Jones, an arrogant US Naval officer, travels to Mars (a jungle planet, not the desert planet of other Mars sci-fi) via magic carpet. There, he gains super strength and telepathic powers, and proceeds to stumble into and out of trouble. There is a war brewing between the beautiful, innocent, sophisticated Hither Folk and the barbaric, industrious Thither Folk; Gullivar fails to prevent the war, and flees back to Earth. He also attempts to claim a vast tract of Mars for himself, travels down a river of death, fails to outwit or defeat his enemies, and doesn’t win the hand of beautiful Princess Heru. Fun fact: Arnold was best known in his own time for the 1890 fantasy novel The Wonderful Adventures of Phra the Phoenician. Note that Edgar Rice Burroughs’s first John Carter novel was likely inspired by Lieut. Gullivar Jones; and the flying cities of Flash Gordon and other, later sci-fi, find their precusor here, in the city of Laputa. Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- Gregory Casparian’s An Anglo-American Alliance (1906). In 1960, Aurora Cunningham, daughter of Great Britain’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs, and Margaret MacDonald, daughter of an American senator, meet at a Ladies’ Seminary and fall in love. However, because they fear social ostracism and negative publicity — Western culture hasn’t caught up with the advanced technology; for example, prenatal sex determination and suspended animation are now possible, a germicide for laziness has been developed, and a Persian astronomer has discovered a new planet on which live a race of electric-wheel-riding aliens — the young women must suppress their true emotions. (Call it: bi-fi.) After graduation, Margaret becomes distraught and ill because she can’t be with Aurora. So — with a brilliant doctor’s help — she undergoes a “mental and physical metamorphosis” transforming her into a man: Spencer Hamilton. Spencer and Aurora marry, and live happily ever after. Fun fact: An Anglo-American Alliance is, as far as I’ve heard, the first lesbian and transgender science fiction novel. The genre wouldn’t see this theme treated openly again until the 1960s.

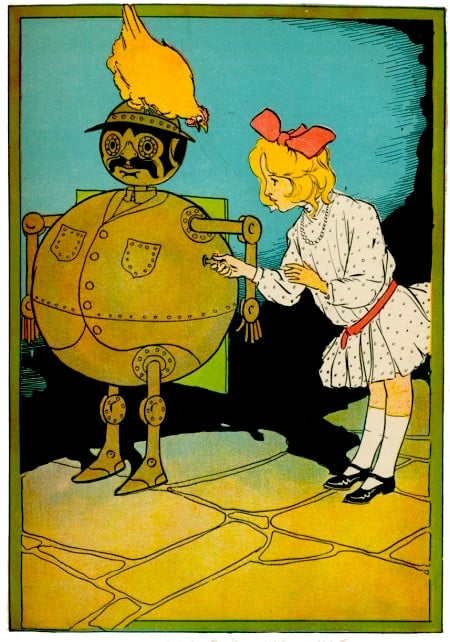

- L. Frank Baum’s Ozma of Oz (1907). The third Oz book, and the first in which we meet one of Baum’s most delightful characters: “He was only about as tall as Dorothy herself, and his body was round as a ball and made out of burnished copper. Also his head and limbs were copper, and these were jointed or hinged to his body in a peculiar way, with metal caps over the joints, like the armor worn by knights in days of old.” From a printed card attached to its neck, Dorothy learns that Tiktok is a “Patent Double-Action, Extra-Responsive, Thought-Creating, Perfect-Talking Mechanical Man Fitted with out Special Clock-Work Attachment. Thinks, Speaks, Acts, and Does Everything but Live.” Though one of the earliest fictional appearances of true machine intelligence, Tiktok is not a free agent like his equally metallic, yet living new friend, the Tin Man — to whom he confides that “When I am wound up I do my du-ty by go-ing just as my ma-chin-er-y is made to go.” Fun fact: Baum revisited this story for his 1913 musical, The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, in which Tiktok sings: “Always work and never play!/Don’t demand a cent of pay!”

- Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star (1908). Leonid, a scientist-revolutionary active in the Russian Revolution of 1905, is befriended by Menni — who turns out to be a Martian in disguise. Leonid, it seems, has been selected by the Martians to visit them — which he does via the “etheroneph,” a nuclear photonic rocket. Mars, Leonid discovers, is a post-revolutionary society — an idyllic communist-esque social order boasting a planned economy and advanced cybernetic control; Martians work only as much as they want to. The “red star” also boasts nuclear fusion and propulsion, atomic weaponry, computers, blood transfusions, and (almost) unisexuality. However, the Martians have run out of resources and are considering an invasion of either Earth or Venus! Sent home, after he kills one of the Martians who threaten to colonize Earth, Leonid rejoins the revolutionary struggle. Fun fact: Bogdanov (1873–1928) was one of the early organizers and prophets of the Russian Bolshevik party; Stalin was a fan of his writing. He followed this novel with a prequel in 1913, Engineer Menni, which detailed the creation of the communist society on Mars.

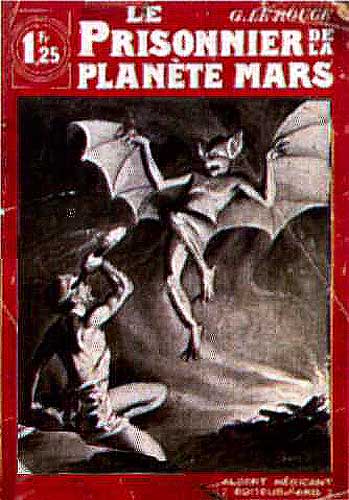

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Le Prisonnier de la Planète Mars (1908). Amateur astronomer Robert Darvel arranges to have himself transported to Mars in a capsule propelled (how else?) by a psychic energy produced by thousands of Indian yogis gathered together as one cosmic soul. Among other observations he makes about Mars’s flora (carnivorous grass) and fauna (giant crabs, jelly-like octopi with pseudo-human faces), Darvel discovers that the planet is inhabited by dull-witted humanoids who are herded and harvested by three species of vampire creatures. The vampires are controlled by squid-like, invisible beings haunting an abandoned city. Even worse, a Great Brain, which inhabits a crystal mountain surrounded by magnetic storms, is controlling the squid-vampire creatures! Mars, it seems, is like an evil version of Oz; L. Frank Baum’s books began appearing in 1900. Darvel finally returns back to Earth, with some of the invisible vampires in tow… thus setting up this book’s 1909 sequel, La Guerre des Vampires. Fun fact: Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- Maurice Renard’s Docteur Lerne, sous-dieu (Doctor Lerne, Undergod, 1908). Returning to the castle where he grew up, after many years away, Nicolas Vermont is surprised to discover that his uncle Frédéric, a retired surgeon, is changed and hostile. Frédéric is engaged in mysterious scientific research, and forbids Nicolas access to his laboratory greenhouses; he also insists that Nicolas not court his protégée, Emma. Nicolas defies both injunctions. When Frédéric realizes that Nicolas has discovered the nature of his research — uncanny plant/animal hybrids! — he temporarily exchanges Nicolas’s brain with that of a bull. (Renard plays with mythology, in this story: the lab is a labyrinth; Nicolas’s bull-brained body is a Minotaur.) Frédéric then develops a means of projecting his own consciousness into a machine — Nicolas’s high-tech automobile. A Symbolist-esque homage to H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau. Fun fact: This was Renard’s first novel. The poet Apollinaire was a fan: “A little marvel of fantasy: charming, cultivated, and effortlessly learned.”

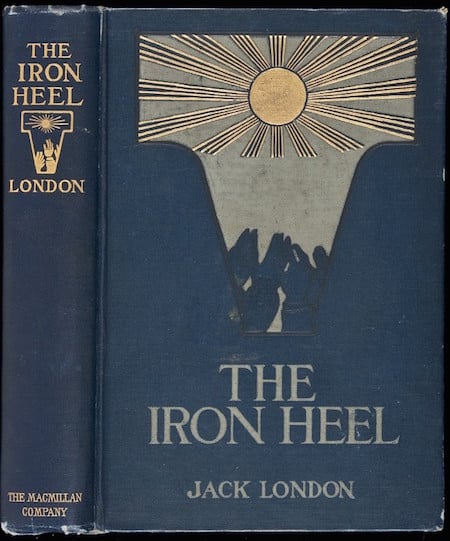

- Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1908). Between the (near-future) years of 1912 and 1932, according to the on-the-scene MS presented here by a far-future historian, an oligarchy known to its foes as the Iron Heel arose in the United States. (We learn, from the future historian, that the Iron Heel would maintain power for 300 years until a socialist revolution finally overthrew it, ushering in a utopian future society.) The Iron Heel is composed of robber barons who have bankrupted the middle class and reduced farmers to serfdom; they use mercenaries to keep laborers — in all industries except steel, rail, and others important to the oligarchs — in check. The Iron Heel has an amazing city built — it’s called Asgard, but let’s face it, it’s Google-era San Francisco — where the proles are wowed by technological advancements but prevented from advancing into the middle class. Fun fact: Sci-fi historians believe that The Iron Heel influenced Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Whether or not that’s the case, Orwell himself described London as having made “a very remarkable prophecy of the rise of Fascism.”

- E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops (1909). Written as a riposte to H.G. Wells’s 1899 technocratic utopia When the Sleeper Wakes, in which Londoners live in a multi-tiered underground society, connected by a vast rail network, Forster’s short novella The Machine Stops takes place in a future civilization in which the outdoors is all but uninhabited. A “Machine” supplies each inhabitant of this global civilization with everything he or she might desire — to a degree where, at this point, few people ever leave their well-appointed apartments. Socialization and entertainment are entirely mediated via the Machine: yes, Forster helped predict the Internet. Who programs the Machine? It’s unclear. In fact, most people are programmed by the Machine. When one courageous individual, Kuno, briefly visits the outside world, he’s shunned by his own mother. Later, when the Machine begins to break down, the inhabitants of this utopian society are utterly helpless. Fun fact: This story was published between the author’s much more famous works A Room With A View and Howards End. Serialized here at HILOBROW.

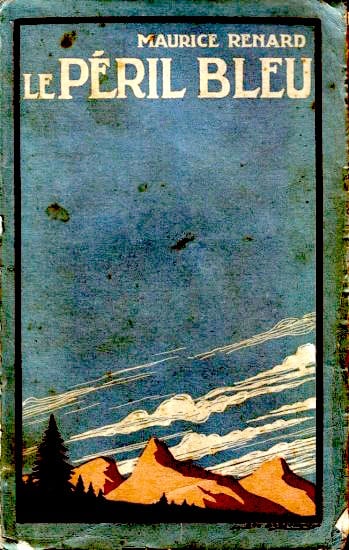

- Maurice Renard’s The Blue Peril (1910). Having discovered a planet swaddled in an impenetrable etheric “ocean,” the Sarvants — an advanced race of space explorers — fish for specimens of its two- and four-legged indigenous life-forms. Like scientists of any species, they dissect their specimens and toss the remains back into the ocean. Having studied and classified these exotic creatures, which are presumably incapable of either suffering or rational thought, the Sarvants preserve and mount a few remaining examples for display. Meanwhile, in eastern France, human body parts are discovered — scattered across the landscape. An investigation is mounted; who is committing these crimes? In the pocket of one of the victims, a written account is discovered: Aliens, it seems, are abducting Earth creatures! The French authorities manage to communicate with the aliens — the Sarvants — who turn out to be tiny insectile creatures capable of assembling and dissembling their bodies with one another at will, in order to form such organs as are necessary for controlling their technology. Astonished to realized that Earth creatures are intelligent (though bizarrely shaped), the Sarvants cease their experiments. Fun fact: The hybrid nature of Renard’s novel — which combines elements of Wellsian science fiction with Poe-esque Gothic horror and detective fiction — caused it to be overlooked, for many years, by sci-fi scholars.

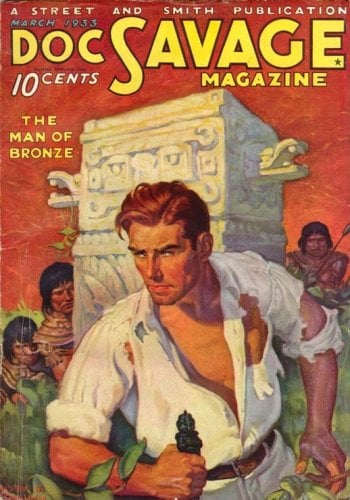

- Jean de La Hire’s The Nyctalope on Mars (1911). Léo Saint-Clair, alias the Nyctalope, is an indomitable Doc Savage-style crimefighter gifted with night vision. As we learn somewhat late in the series, he’s also equipped with an artificial heart, which he gained after being tortured and nearly assassinated, and which prevents him from aging. In this, the first of a series of exploits published through the mid-1940s, the Nyctalope battles Oxus, leader of the sinister Society of the Fifteen, who is plotting to conquer Earth from his secret base on Mars. Later, however, he allies himself with Oxus and the planet’s benign inhabitants in order to defeat H.G. Wells’ evil Martians. Then he gets married! Fun fact: French title: Le Mystère des XV. In subsequent adventures, the Nyctalope will travel to the planet Rhea, discover a lost civilization of Amazons in Tibet, and have himself cryopreserved — so that, 170 years later, he can defeat an enemy who has also been frozen (hello, Demolition Man and Austin Powers).

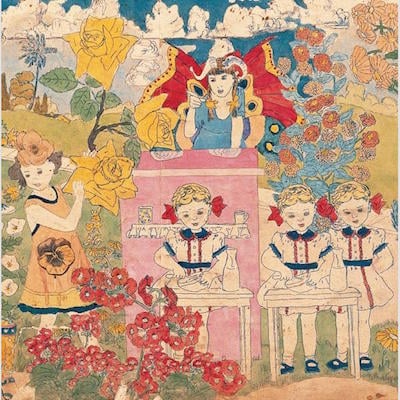

- Henry Darger’s In the Realms of the Unreal (1911–39). Darger’s 15,000-page novel is bound in fifteen immense volumes, three of which consist of several hundred watercolor paintings on paper derived from magazines and coloring books. Most of the book, titled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, follows the graphically violent, epic adventures of seven princesses who assist a daring child-led rebellion against the evil regime of child slavery imposed by the Glandelinians. The setting is a war-torn planet around which the Earth orbits. The first nine volumes were most likely written between 1911 and 1928; the remaining volumes were completed by 1938 or 1939. Fun fact: Henry Darger was a reclusive man who worked as a hospital custodian in Chicago; Darger’s landlords came across his work shortly before his death, in 1973, and preserved it. Darger is today one of the most famous figures in the history of “outsider art.”

- J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911). Victor Stott is a giant-headed “supernormal” child mutated — in the womb — by his parents’ desire to have a son born without habits. After surveying science, philosophy, history, literature, religion, the best that has been thought and said, the Wonder is dismissive: “So elementary… inchoate… a disjunctive… patchwork.” Young Victor’s adult interlocutors are shattered by his statements about the nature of the universe and human progress; his philosophy begins with rejecting “the interposing and utterly false concepts of space and time,” and ends with the notion that life and all matter are merely “a disease of the ether.” Alas, his interlocutors are unable to live without illusions; they reject the Wonder’s disenchanting insights. Worse, the superboy also makes an enemy of the local clergyman, who (the reader is left to suspect) murders him. The narrator’s eulogy: “He was entirely alone among aliens who were unable to comprehend him, aliens who could not flatter him, whose opinions were valueless to him.” Fun fact: The first SF novel of real importance about intelligence; it’s the ancestor of Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End and A.E. Van Vogt’s Slan.

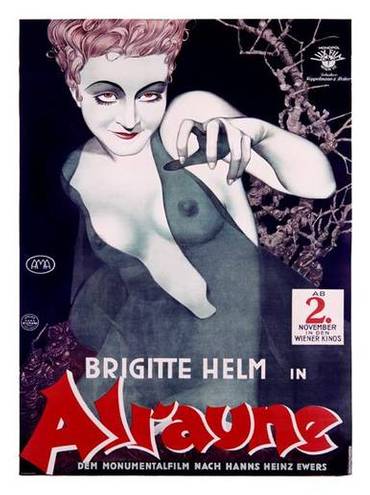

- Hanns Heinz Ewers’s Alraune (1911). With the help of his ubermensch nephew, Frank Braun, scientist Jacob ten Brinken collects the semen of a condemned man (ejaculated at the moment of the man’s execution) and uses it to impregnate a prostitute. He is conducting a test of medieval German folklore about the fertility powers of the mandrake root, which was believed to be produced by the semen of hanged men under the gallows; witches who made love to the mandrake root, it was believed, produced offspring who had no soul. Alraune, the fruit of this experiment, cannot overcome her genetic inheritance: She is a sociopathic, perhaps vampiric child; and as an adult, she drives lovesick men — including Jacob ten Brinken — to ruin and death. However, Alraune meets her match in Frank Braun, who is worse than a vampire: He’s a lawyer. The novel’s final chapters are a catalog of the couple’s outrageous sexual practices. Fun fact: The book’s English translation was made, in 1929, by Guy Endore. This is the second of three Frank Braun novels, the others being The Sorceror’s Apprentice (1907) and Vampire (1927). An early member of the Nazi Party, Ewers alienated its leadership by insisting that the Nazi obsession with blood (genetics) led inevitably, properly, to vampirism.

- Alfred Jarry’s Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique suivi de Spéculations (w. 1898, p. 1911, trans. as Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician). The scientist-inventor Dr. Faustroll travels — in a high-tech (capillarity, surface tension, equilateral hyperbolae are involved) amphibious copper skiff — from the Seine from point to point through the neighborhoods and buildings of Paris. He is accompanied by his Wookiee-like baboon butler Bosse-de-Nage, and also by the story’s narrator, Panmuphle, a lawyer attempting to convict the good doctor of debt. Opposed to mainstream science’s principe de l’induction, Faustroll practices a “science of imaginary solutions” that he calls ’pataphysics. Whereas the inductive reasoner brackets his imagination and blinkers his perspective, the ’pataphysician embraces as many perspectives as possible; no conjecture is regarded as impossible. Spoiler alert: Dr. Faustroll dies! But he manages to send a telepathic letter to Lord Kelvin describing the afterlife and the cosmos. Fun fact: Jarry is best known as the author of the proto-Dada play Ubu Roi. This posthumously published novel is regarded, by exegetes, as the central work to his oeuvre.

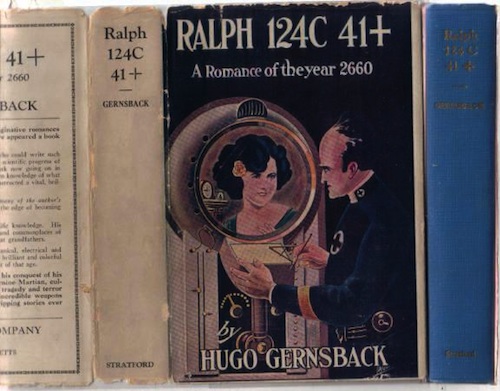

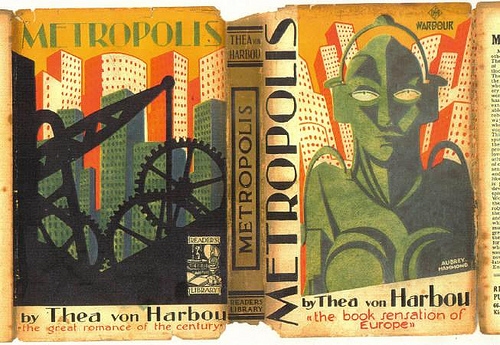

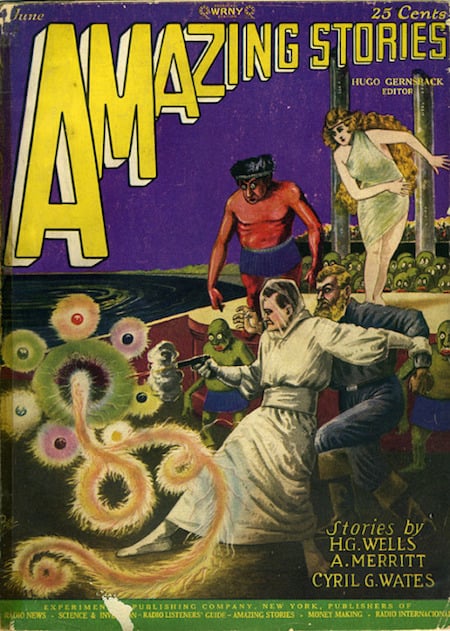

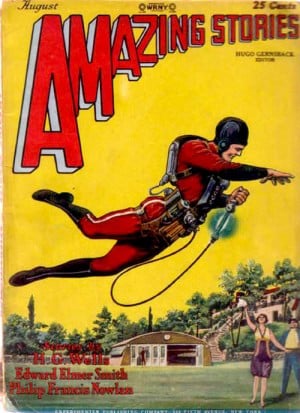

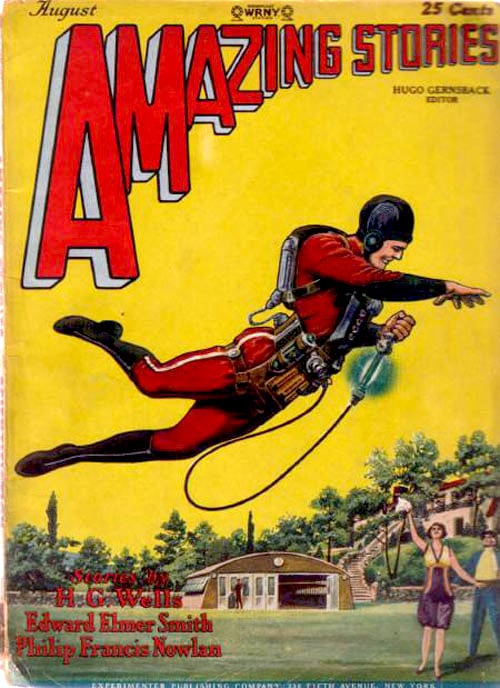

- Hugo Gernsback’s Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660 (1911–1912). Ralph One-to-foresee-for-an-other (get it?) is a great American scientist, and a superior type; the honorific “plus” at the end of his name signifies it. But what kind of big-headed superman story is this, anyway? The polar fleece-wearing citizens of solar-powered, geothermally heated New York don’t fear or resent Ralph; in fact, they’ve erected a glass-and-steelonium luxury tower for him in Union Square. Ralph isn’t an evil genius; he’s something of a bore, and so is his techno-utopian society. Except maybe when his girlfriend is kidnapped by a Martian! Despite the wooden prose and juvenile adventure, this Edisonade is worth a read because of all the technology it accurately predicts: e.g., fluorescent lights, microfilm, radar, television. Also, I suspect that we’re on the cusp of seeing the Hypnobioscope, which allows you to avoid subscribing to newspapers in your sleep, hit the Apple Store. Fun fact: Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination. In 1926, Gernsback launched the first sci-fi pulp, Amazing Stories; later, he’d also publish Wonder Stories. Science fiction’s Hugo Award is named after him.

- William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land (1912). In the far future, what remains of the human population dwells deep below the Earth’s frozen surface in a pyramidal fortress-city that for centuries has been surrounded by giants, “ab-humans,” enormous slugs and spiders, and malevolent Watching Things from an alien dimension. The unnamed narrator, along with apparently every other surviving human, lives trapped in the Last Redoubt, a eight-mile-high metal pyramid-city constructed by their ancestors using now-forgotten technologies. The pyramid is protected from the Slayers, who surround and observe it constantly, by mysterious Powers of Goodness, and also by a massive force-field powered by the “Earth Current” — a Tesla-esque force drawn from the planet itself. When the narrator receives a telepathic distress signal from a young woman whom (in a previous incarnation) he’d once loved, he sallies forth on an ill-advised rescue mission — into the uncharted and unfathomable Night Land. Fun fact: “One of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.” — H.P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927). Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Erik Davis.

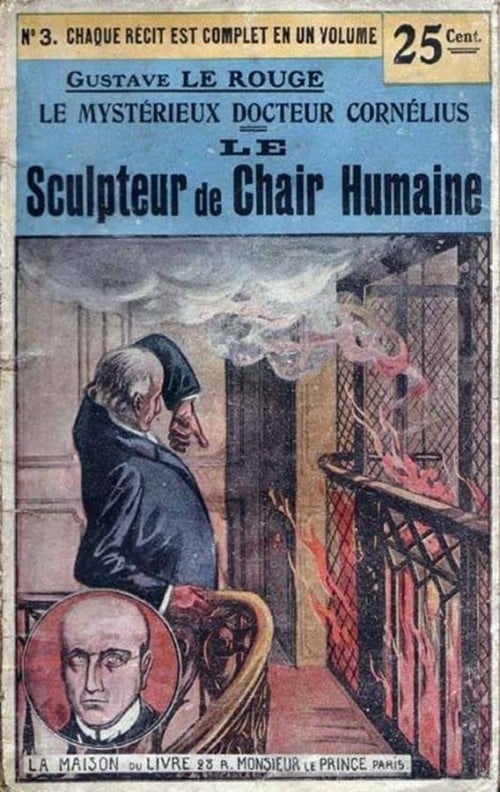

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Le Mystérieux Docteur Cornelius stories (1912–13). Dr. Cornelius Kramm is a brilliant, New York- and Paris-based cosmetic surgeon (nicknamed the “Sculptor of Human Flesh”) who, along with his brother Fritz, secretly rules an international criminal empire called the Red Hand. One of Cornelius’ top agents is Baruch Jorgell, a sadistic sociopath; Dr. Cornelius uses his skills as a surgeon to alter Jorgell’s appearance, making him unrecognizable. The Red Hand’s growing influence — Le Rouge’s saga was serialized in eighteen volumes — leads to the creation of an alliance of scientists, industrialists, and adventurers who fight back. There is a romance angle: One of the adventurers, Harry Dorgan, is in love with Baruch’s sister. After a globe-hopping battle, the Red Hand is defeated and Dr. Cornelius killed — or is he? Fun fact: The Dr. Cornelius stories, in order, are L’Énigme du Creek Sanglant, Le Manoir aux Diamants, Le Sculpteur de Chair Humaine, Les Lords de la Main Rouge, Le Secret de l’Île des Pendus, Les Chevaliers du Chloroforme, Un Drame au Lunatic Asylum, L’Automobile Fantôme, Le Cottage Hanté, Le Portrait de Lucrece Borgia, Coeur de Gitane, La Croisière du Gorill-Club, La Fleur du Sommeil, Le Buste aux Yeux d’Émeraude, La Dame aux Scabieuses, La Tour Fiévreuse, Le Dément de la Maison Bleue, and Bas les Masques.

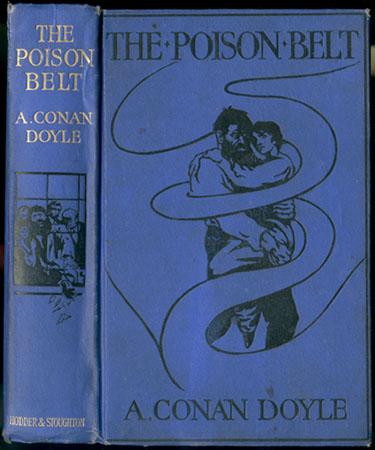

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). Having assembled a crew of adventurers, the brilliant, blustering physiologist and physicist Prof. Challenger journeys to a South American jungle… in search of a lost plateau crawling with iguanodons. It’s a ripping yarn — the first popular dinosaurs-still-live tale, prototype for everything from King Kong to Jurassic Park. At the same time, however, it’s a philosophical novel, one which animates — in a thrilling, humorous fashion — the author’s obsessive drive (also seen in his Sherlock Holmes stories) to reconcile the claims of logical reason and intuition. Challenger’s foil, the respected zoologist Professor Summerlee, is an avatar of the inductive method of reasoning; we first meet him when he rises from the audience at a lecture in order to accuse Challenger of making non-testable assertions. Although Summerlee is an admirable figure, in the end his refusal to accept any facts that haven’t been revealed by means of instruments and techniques of observation and experiment make him look like a dogmatic nincompoop. Plus: Battles with proto-humanoids! Fun fact: Doyle followed up this bestselling novel with The Poison Belt (1913) and The Land of Mist (1926), as well as two short stories about Challenger. Reissued by Penguin Classics.

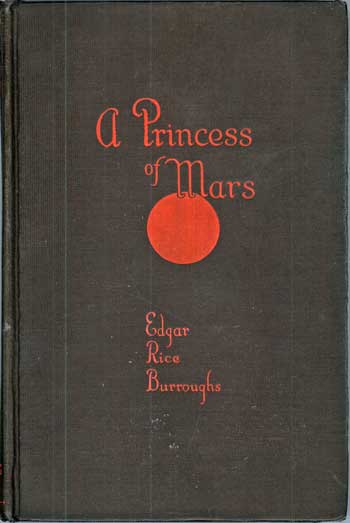

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars (serialized 1912; in book form, 1917). Transported to Mars — via something like astral projection — ex-soldier John Carter finds himself embroiled in a war between the Red and Green Martians. The barbaric, nomadic Green Martians are 15 feet tall, with six limbs; they inhabit the abandoned cities of Barsoom (that is, Mars). The Red Martians, meanwhile, are civilized humanoids, organized into city-states that control Barsoom’s water. Carter’s unusual coloring, and the extraordinary strength he is afforded by the planet’s weak gravity, make him uniquely capable of forming alliances among honorable members of both Barsoomian peoples. He falls in love with Dejah Thoris, beautiful daughter of a Red Martian chieftain, and rescues her from both Green and Red Martians before leading a Green Martian army against the enemy of Thoris’s state. Fun facts: Serialized pseudonymously, in the same year that Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes appeared, this is the first in the author’s popular “Barsoom” planetary romance series. It was originally titled Under the Moons of Mars. PS: I might be in the minority, on this subject, but I quite enjoyed the book’s 2012 Hollywood adaptation, John Carter.

- Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague (1912). Outside the ruins of San Francisco, a former UC Berkeley professor recounts the chilling sequence of events — a gruesome pandemic which killed nearly every living soul on the planet, in a matter of days — which led to his current lowly state. Modern civilization has fallen, and a new race of barbarians, descended from the world’s brutalized workers, has assumed power. Over the space of a few decades, all learning has been lost. In the post-apocalyptic social order, women are degraded and beaten: Vesta Van Warden, wife of the richest man in America before the plague, we learn from the ancient James Howard Smith, became the chattel of one of her former servants, a man known only as Chauffeur. Predatory nomads — members of the Chauffeur Tribe — named Hoo-Hoo and Hare-Lip roam among the ruins of San Francisco. And Smith, formerly a professor of literature at UC Berkeley, is reviled by his juniors for being literate. Fun fact: Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Matthew Battles.

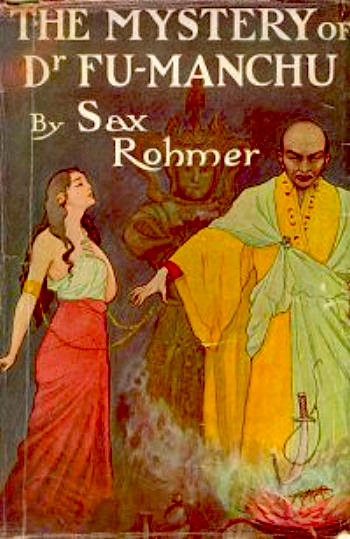

- Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1912—1913). In this first Fu Manchu novel, assembled in 1913 from stories published in magazines during 1912, colonial police commissioner Nayland Smith is in hot pursuit of Fu Manchu, an agent of a Chinese secret society, the Si-Fan. A brilliant scientist and criminal mastermind, Fu Manchu has relocated from China and Burma to East London’s Limehouse district, from where — Smith believes — he is orchestrating a wave of assassinations targeting Western imperialists. Oh, and he appears to be kidnapping Europe’s best engineers and smuggling them back to China for some nefarious purpose, too! Fun fact: Rohmer’s Fu Manchu character would inspire racist depictions of Asian sci-fi/fantasy villains from Ming the Merciless to Dr. No. The character was also featured in movies, TV, radio, comic strips, and comic books through the middle of the century; these latter entertainments — which depicted Rohmer’s villain with a long, drooping mustache (not mentioned in the books), has led to that style of facial hair becoming popularly known as a “Fu Manchu.”

- George Allan England’s The Vacant World (serialized 1912). The first part of the author’s Darkness and Dawn trilogy. When engineer Allan Stern and his beautiful secretary, Beatrice, wake up on the upper floor of a ruined Manhattan skyscraper, over a thousand years in the future, they are understandably confused. What happened? It’s a Rip Van Winkle story in which an asteroid has destroyed most life on Earth; New York lies in ruins. Wild animals and savage, mutated humans roam the streets — alas, I’m sorry to report that they are African-Americans. Allan uses his skills to make explosives, build bridges, fly bi-planes, and so forth; Beatrice joins him in discussions of how to rebuild civilization along utopian lines. This is pulp fiction, with a socialist edge. It’s not well-written, but it’s of historical interest, because — along with Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague — it’s an early post-apocalyptic yarn. Fun fact: England was an American writer, and explorer who, later in life, unsuccessfully ran for Governor of Maine as a socialist. The other books in the Darkness and Dawn trilogy are Beyond the Great Oblivion (1913) and Afterglow (1914).

- J.D. Beresford’s Goslings (1913). When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling (one of the few survivors) abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where after some adventures they find meaningful roles in a female-dominated agricultural commune. The women of the commune shed their vanity and socially imposed role restrictions; along with one male, the intellectual Thrale, they must learn to come together as a community for survival. But the Goslings’ idyll is threatened by their elders’ prejudices about free love! Fun fact: The book was titled A World of Women when it was released in the US. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Astra Taylor.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (1913). Three years after having led an expedition into a South American jungle in search of surviving pterodactyls and iguanodons, the controversial scientist George Edward Challenger telegrams his dino-hunting comrades: “Bring oxygen.” Once they arrive at his country home south of London, Challenger reveals that the planet is about to pass through a belt of poisonous ether (astrophysicists now prefer “dark matter”), which will destroy all life on Earth. However, Challenger has transformed his wife’s dressing room into an airtight chamber, so they can witness the end of the world. Why — in this first sequel to The Lost World — did Doyle lock his adventurers into a room? Because this is an epistemological thriller: At the extremity of experience, Summerlee, an avatar of the inductive scientific method, and Challenger, an avatar of the simultaneously intuitive and logical “abductive” method of acquiring knowledge, hash it out. Fun fact: Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Joshua Glenn and an Afterword by Gordon Dahlquist.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Gods of Mars (1913, as a book 1918). The second installment in Burroughs’s Barsoom series. Returning to Mars after ten years, John Carter materializes in the Valley Dor: the supposedly paradisial secret location to which Barsoomian’s travel once they’ve reached 1,000 years of age. Joined by his friend Tars Tarkas, the 15-foot-tall, double-torsoed, green-skinned Martian, Carter discovers that Barsoomians are actually killed and enslaved in the Valley Dor! (This context is strongly reminiscent of Philip K. Dick’s 1966 novel The Unteleported Man, don’t you think?) The Therns, a white-skinned, cannibalistic race of self-proclaimed gods, must be defeated — but Carter and Tarkas must also contend with Plant Men, Black Pirates, the green warriors of Warhoon, and the Zodangans. Phew! Fun fact: First published in All-Story as a five-part serial, this novel was written at the same time as Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes.

For context, see my list of the Best Nineteen-Teens Adventure.

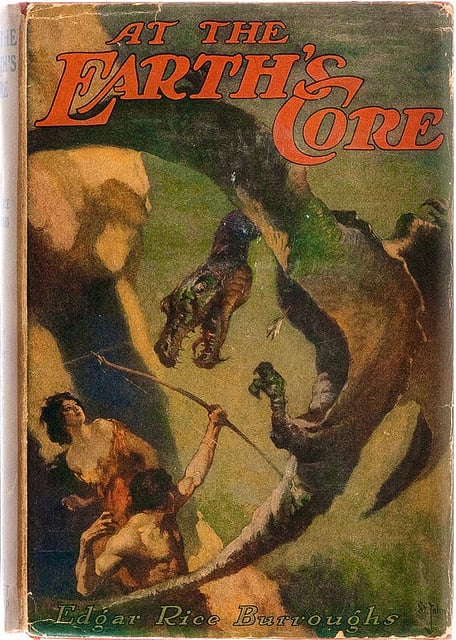

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s At the Earth’s Core (1914). Thanks to his futuristic “iron mole” machine, mining engineer David Innes discovers that the Earth is hollow. At the planet’s center is Pellucidar, a land — lit by a miniature Sun — in which stone-age humans are dominated by the Mahars, flying reptiles who are highly intelligent and evolved. Innes must battle prehistoric creatures and proto-humanoids, rescue the lovely Dian, and lead a revolt against the Mahars. Oh — and somehow return to the surface of the planet. The first of seven Pellucidar novels. Fun fact: H.P. Lovecraft was a fan; check out his 1931 adventure At the Mountains of Madness. It’s also worth mentioning that Burroughs’s Tarzan character eventually visits Pellucidar.

- Inez Haynes Irwin’s Angel Island (1914). Shipwrecked on an uncharted island, five men encounter five winged women, rebels from their tribe who’ve decided to fly south instead of north. Frustrated by how aloof and skittish the women are, the men clip the women’s wings. At first, four of the five women enjoy the attention — all but one, their leader, Julia — and marry four of the men. However, the domesticated women soon realize that married life is a form of servitude, and they lament their lost freedom. When they bear children (mostly wingless boys) and discover that the one winged girl-child will also have her wings clipped, the domesticated women take a stand. They demand rights for women — after which things change on the island. The women’s wings are no longer clipped. Julia gets married: symbolically, her child is a winged boy. Fun fact: Inez Haynes Irwin, who’d been active in the suffragist movement, was fiction editor of the left-wing periodical The Masses.

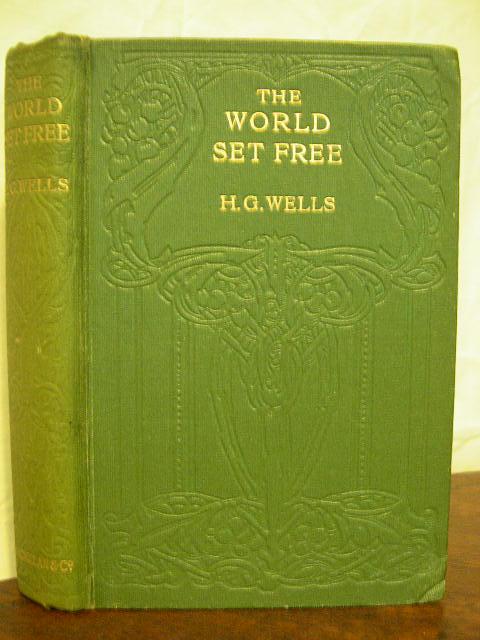

- H.G. Wells’s The World Set Free (1914). Building on the recent discovery that “the atom, that once we thought hard and impenetrable, and indivisible and final and — lifeless — lifeless, is really a reservoir of immense energy,” Wells conjures a 1950s England in which clean, efficient atomic engines have transformed life for the better. Alas, a world war breaks out, in which atomic bombs wipe out the world’s great cities. Worldwide civilization is on the brink of collapse, when a conference of enlightened monarchs, presidents, powerful journalists, and scientists gathers in order to establish a peaceful one-world order. When one Kissinger-like figure begins to strategize about maintaining national autonomy and monarchical authority within this utopian world government, another character shuts him up with one word: “BANG!” Fun fact: The astrophysicist Leó Szilárd, who worked on the Manhattan Project, claimed that The World Set Free helped him conceive of the nuclear chain reaction. See my essay on The World Set Free and Wells’s two books of floor games for children.

- Raymond Roussel’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Locus Solus (1914). Invited to Locus Solus, the suburban estate of the reclusive, fabulously wealthy French scientist Martial Canterel, a group of his colleagues are introduced to strange and complex inventions and oddities: a wind-powered paving bot, which constructs elaborate mosaics of human teeth; the preserved head of 18th-century revolutionary Danton, which speaks when stimulated by a hairless cat; a vast aquarium in whose “aqua-mican” terrestrial mammals can breathe (hm — a similar appratus had appeared in Gustave Le Rouge’s 1909 sci-fi adventure La Guerre des Vampires); a doctor who painlessly removes fingernails and replaces them with mirrors; and so forth. Within an enormous glass cage, eight zombies whom Canterel has revived (thanks to his invention, “resurrectine”) act out the most important incidents of their lives — over and over again, sometimes in the company of their still-living family members! Behind some of Canterel’s artifacts lie strange and disturbing stories (and stories within stories); behind others, delightfully surreal ones. We’re also treated to sober explications of the technology making each exhibit possible. It’s a far-out, macabre wunderkammer, and a philosophical novel exploring what Adorno and Hortkheimer would later call the dialectic of Enlightenment — i.e., the irrationality of science, the logic of obsession. Fun fact: Roussel composed Locus Solus using eccentric, punning guiding principles — explained in his posthumous text, How I Wrote Certain of My Books (1935) — that would influence later experimentalists. John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, James Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch edited a 1960s journal called Locus Solus (after Roussel’s novel), which has been called the New York School of poets’ manifesto.

- G.K. Chesterton’s The Flying Inn (1914). When a British politician, Lord Ivywood, sets out to Islamize Great Britain — so that he can enjoy the benefits of polygamy — he cleverly enlists the assistance of the nation’s “smart set,” who are all too eager to embrace trendy, “Eastern” fads like Islam. Among other changes, Ivywood pushes through laws requiring that alcohol only be sold by an inn displaying a sign… and banning inn signs. Patrick Dalroy, a hard-drinking Irishman, and Humphrey Pump, dispossessed landlord of one of the shuttered English inns, take to roaming the countryside with a cart (later, a motorcar) full of rum. Meanwhile, we discover that Ivywood is a pseudo-Nietzschean figure bent on destroying Christianity and Western culture… and that he is smuggling a Turkish army into England! Fun fact: According to some critics, Chesterton makes this book’s reader complicit in an architecture of unquestioned privilege and received prejudice.

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915, serialized). Charlotte Perkins Gilman, sociologist and author best known for “The Yellow Wallpaper,” here gives us a Lost Race story — in which the Lost Race is composed of women who reproduce without the aid of men. When young Van Jennings and his friends — Terry and Jeff — invade an isolated society composed entirely of women, they carry with them not only brightly colored scarves and beads but sexist ideological baggage. Jeff is an idealist who regards women as things to be served and protected; Terry is a cynic who views women as conquests. Van, a sociologist, is uniquely able to apprehend the social construction of gender roles… and the fact that a woman-only social order is superior in every way to western civilization. The three men attempt to flee, but in vain. Will they be reeducated? Fun fact: The most famous feminist fantasy of the period. Herland was serialized here at HILOBROW.

- Frigyes Karinthy’s Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage (1916). It’s 1914, and Jonathan Swift’s Lemuel Gulliver is eager to go to sea again. He signs on as a surgeon on a British ship, only to be torpedoed, then picked up by a UFO and transported to Faremido, a planet ruled by intelligent machine-folk. They regard organic life as a loathsome disease of matter, so they’re pleased that the Great War looks likely to exterminate humankind. Agreeing that the Faremidoans (whose society is peaceful, and whose fa-re-mi-do language is musical) are superior beings, Gulliver accepts an injection of their own brain-matter — quicksilver and minerals — into his head. Now a proto-cyborg himself, Gulliver is sent back to England, where he finds it difficult to adjust to the irrational horrors of everyday life. Fun fact: The sequel to this Hungarian novella is Capillária (1921).

- J.A. Mitchell’s Drowsy (1917). Cyrus Alton, a telepath nicknamed Drowsy because of his drooping eyelids, grows up to attend MIT and become a brilliant scientist. (Call it: psi-fi.) He invents a spaceship equipped with an antigravity mechanism, and flies to the moon, returning with a fantastic diamond… and then, impelled by a psychic bond with a childhood sweetheart, rescues her before she joins a convent. Of greater interest than these rather silly adventures, though, is Mitchell’s account of Drowsy’s childhood. Is he the first of a new species: homo superior? Like the title character of J.D. Beresford’s Hampdenshire Wonder, young Drowsy’s evolved worldview offends his narrow-minded elders. Especially when, for example, he cuts his favorite illustrations out of a Bible; or insists on the morality of untruths; or demands to know why “teacher doesn’t tell us things worth knowing.” Like Daniel Clowes’s Enid Coleslaw, that is to say, Drowsy is a cranky middle-aged freethinker in a child’s body. Fun fact: The author, a Harvard dropout and idler, founded the original LIFE Magazine, later purchased by Henry Luce, in 1883.

- Victor Rousseau’s The Messiah of the Cylinder (1917). After sleeping for a century, Rousseau’s protagonist, Arnold Pennell, awakens — like the protagonist of H.G. Wells’s The Sleeper Wakes (1910) — in a socialist, “scientific world freed of faith and humanitarianism.” He is horrified not only by the dazzling, skyscraper-dominated London of the future, but by Britain’s tyrannical utopian order, which is maintained though constant sloganeering and other forms of thought control. Having become an iconic figure to the people of the future, who have been waiting for a Messiah to restore to them their ancient liberties, Pennell leads a revolution — the goal of which is to help Russia restore a moralistic aristocracy in Britain. Fun fact: Serialized, from June–September 1917, in Everybody’s Magazine, The Messiah of the Cylinder is considered one of the first American dystopian stories. It is also one of the first sf stories to use the term “ray gun.”

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Land That Time Forgot (1918). During WWI, a shipwrecked American shipbuilder (Bowen Tyler), beautiful Frenchwoman Lys La Rue, and the crew of a British tugboat capture a German U-boat — and sail it to the Antarctic, dodging Allied ships — until they find themselves drawn to an uncharted magnetic island… inhabited by beast-men in various states of evolution. The British and German sailors agree to work together, under Tyler, to survive (Swiss Family Robinson-style) until they can somehow refuel the U-boat. However, when Lys is captured by proto-humans and the Germans abscond with the sub, Tyler must set off into the interior of the island. Fun fact: Some Burroughs fans consider this the author’s best novel. Confusingly, in 1924 it was published — along with two sequels (The People That Time Forgot, Out of Time’s Abyss) under the omnibus title The Land That Time Forgot. Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook (serialized 1918–1919). When adventurers Bastin, Bickley, and Arbuthnot are marooned on a South Sea island, they discover two Atlanteans in a state of suspended animation. One of the awakened sleepers, Lord Oro, is a superman — the last king of the Sons of Wisdom, who’d relied on hyper-advanced technology to subjugate the planet’s lesser peoples. The other is Oro’s sexy daughter, Yva… who falls in love with Arbuthnot. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front. Why? To determine whether or not he should once again employ an infernal chthonic machine to drown the worthless human race, as he’d done 250,000 years earlier! Fun fact: One of the few SF tales by the author of King Solomon’s Mines and She. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by James Parker.

- Owen Gregory’s Meccania: The Super-State (1918). In the year 1970, Ming, a young Chinese traveler, visits the Central European state of Meccania. (This dystopian, proto-totalitarian state is obviously based on Germany; its neighbors are “Franconia” [France], “Luniland” [Britain], and “Lugrabia” [Russia].) Constantly monitored by official guides, Ming gets into more trouble when his personal diary — in which he notes that Meccania’s militaristic government dominates social life, that the country is a place of “perpetual propaganda” where dissenters are sent to mental hospitals and concentration camps, and that everyday life there is “an odd mixture of arrogance, xenophobia, over-punctiliousness, over-organization, chauvinism, and rigidity” does not match the records of his guides with perfect exactness. The state maintains a eugenic breeding program; all telephone conversations are monitored; and workers’ actions are monitored and regulated in precise detail.

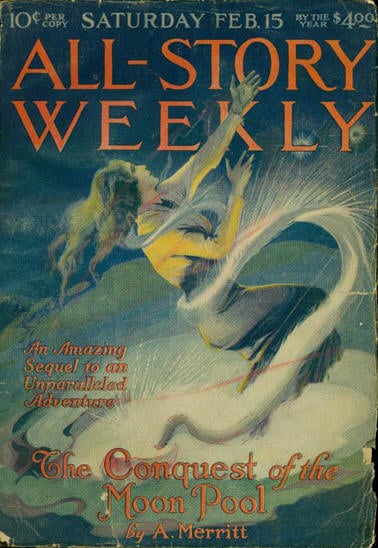

- A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool (1918–1919). The scientist Dr. Goodwin, the dashing pilot/adventurer Larry O’Keefe, and others descend into the Earth’s core — in pursuit of an entity that sometimes rises to the surface of the planet and captures men and women. In addition to a lost race of powerful, handsome “dwarves” and a lost race of froglike humanoids, the explorers discover that the entity they seek is the Dweller, essentially an AI created by an advanced race, known as the Shining Ones (ancient astronauts?). The Dweller has the capacity for great good and great evil, but over time is has tended to become evil rather than good. Yolara, a beautiful woman who serves the Dweller, falls in love with O’Keefe; so does Lakla, a beautiful woman who serves the Shining Ones. The adventurers must persuade or coerce the Dweller to become good — but how? Fun fact: Merritt was a best-selling author during this period. The Moon Pool, which originally appeared as two short stories in All-Story Weekly, is sometimes cited as an influence on Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu.” Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- Rose Macaulay’s What Not: A Prophetic Comedy (1919). At some point after the Great War [that is to say, after the First World War, which ended a few months after Macaulay wrote this book], in a Britain where people travel by underground train and “street aero,” a government ministry — the Ministry of Brains — decides to increase national brain-power, and stave off the coming idiocracy, through a program of compulsory selective breeding. The propaganda efforts in support of this endeavor are amazing, and wide-reaching… not just official posters, but newspaper editorials, business advertisements, contests, and more. However, when it’s discovered that the head of the Ministry has secretly married, even though — because there is “deficiency” in his family — he is not allowed to do so, the Ministry is burned down. The book ends on an ambiguous note: Is the victory of “human perverseness, human stupidity, human self-will” over autocratic bureaucracy a triumph? Or not? Fun fact: When British censors discovered that What Not ridiculed wartime bureaucracy, its planned 1918 publication was stopped. Macaulay is best known, today, for her award-winning final novel, The Towers of Trebizond (1956).

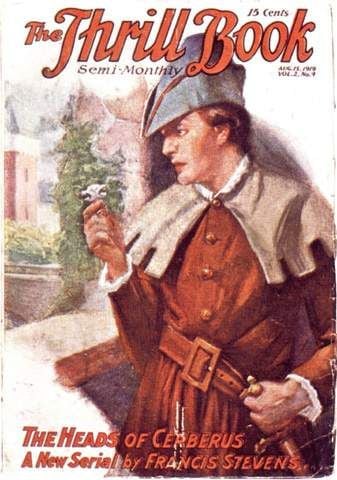

- Francis Stevens’s The Heads of Cerberus (serialized in Thrill Book, 1919; as a book, 1952). In this pre-PKD epistemological thriller, three Philadelphians accidentally inhale dust from an ancient vial whose cap is shaped like the mythological three-headed dog Cerberus. It turns out that the dust was invented by a scientist who has discovered parallel universes. They are transported into a strange land populated by supernatural beings, then whisked back to Philadelphia… which has changed. It is the year 2118, and Philadelphia has become a dystopian nation-state ruled by the “Penn Service.” Ordinary citizens are numbered, not named; the Liberty Bell has become an object of veneration it is is believed that the land will dissolve if it is ever rung. Is this Philadelphia real? Are they somehow creating it? What is reality? Fun fact: Gertrude Barrows Bennett (1883–1948), who published under the pseudonym Francis Stevens, was a pioneering American female writer of fantasy and science fiction. She has been described as “the woman who invented dark fantasy.”

- David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus (1920). An adventurous Scot, Maskull, encounters a semi-divine trickster figure, Krag, who whisks him from Earth to the planet Tormance, orbiting Arcturus. Reality is fluid, on Tormance — which turns out to be less an actual planet than a kind of proving-ground of the soul. Each chapter introduces a new philosophical system, religious idea, and concept of the true nature of the world — and then, having persuaded Maskull (and the reader) to believe in these things, mocks us for doing so. (C.S. Lewis on Lindsay: “He is the first writer to discover what ‘other planets’ are really good for in fiction… To construct plausible and moving ‘other worlds’ you must draw on the only real ‘other world’ we know, that of the spirit.”) Maskull is tormented by Crystalman, who bedevils humankind with comforting illusions and false pleasures. Falseness, it transpires, is winning the war against truth; only Krug, who maintains his sense of humor, and who claims to be known on Earth as “Pain,” can hold his own in the fight. Maskull’s trials and tribulations release his authentic self: Nightspore, who must return to Earth and save more souls from Crystalman’s clutches! Fun fact: A Voyage to Arcturus has been described as Calvinist (because pleasure is rejected in favor of instructive pain), Gnostic, Nietzschean, and psychedelic. Ballantine Books’s influential Adult Fantasy series rescued the book from obscurity in 1968; and more recently, it was reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

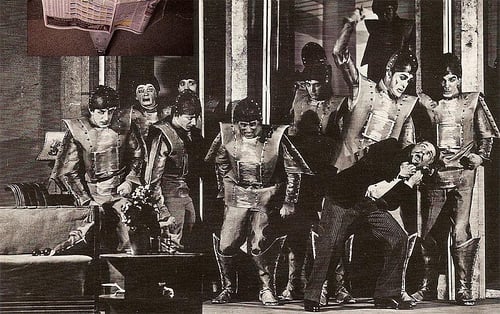

- Karel Čapek’s R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots (1920–1921). In the 1960s, the factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots, has shipped hundreds of thousands of “Robots” — biological humanoids designed for cheap labor — around the world. The Robots, which have a limited life span, are supposedly soulless. Not so, claims Helena Glory, a liberal activist who marries the factory’s GM (who envisions a utopia in which humans won’t have to do any work). At Helena’s urging, R.U.R.’s scientists develop Robots tricked out with extra humanity… at which point they rise up and exterminate humankind. In an epilogue, Alquist, R.U.R.’s construction engineer and the last surviving human, give his blessing to two new-model Robots, Primus and Helena, who have discovered love. Fun fact: The term robot, coined by Čapek’s brother Josef, who (like Karel) feared the unlimited power of corporations, comes from the Czech for “serf labor.” Reissued by Penguin Classics.

- Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins (1920). A proto-Idiocracy satire on H.G. Wells’s utopian novels. Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, ex-artillery officer and physics instructor Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — on the eve of a new Dark Age! England has become a neo-medieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Though he is at first disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress (“He had held the comfortable belief that mankind was advancing in conveniences and the amenities of life by regular and inevitable degrees”), Tuft eventually decides that post-civilized life is simpler, more peaceful (“We used to feel that we were living on the edge of a precipice — every man by himself, and all men together, lived in anxiety”). That is, until northern English and Welsh tribes threaten London — at which point Tuft sets about reinventing weapons of mass destruction. Fun fact: “The first of the many British postwar novels that foresee Britain returned to barbarism by the ravages of war.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed. (1976). Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Tom Hodgkinson.

- Maurice LeBlanc’s Le Formidable Evènement (1920); 1922 in English, as The Tremendous Event). In the near future, an earthquake creates a new landmass linking England and France. Chaos ensues — rivers are blocked, coastal cities damaged, ships shipwrecked. Although bands of vicious criminals roam the newly exposed land, looting the shipwrecks, an English aristocrat and his daughter, Isabel, must risk these dangers in order to retrieve their family treasure, which was on one of the stranded ships. Isabel is captured, and faces a fate worse than death. English and French military forces, meanwhile, are converging — both intent on claiming the new territory. Simon Dubosc, a handsome Frenchman in love with Isabel, joins forces with a band of American Indians (!) who happened to be visiting, and rides across the desert-like terrain to Isabel’s rescue. Fun fact: Maurice Leblanc is best known for his stories about Arsène Lupin, gentleman burglar and detective.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1921). This dystopian novel, set in a totalized social order whose citizens (“ciphers,” with numbers for names) eat, sleep, work, and even make love like clockwork, extrapolates from the rhetoric of those communists who advocated extending Taylorism and other capitalist scientific-management techniques beyond the factory into all spheres of life. Zamyatin’s fable isn’t anti-utopian, but anti-anti-utopian. Like his protagonist, mathematician and rocket designer D-503, the author longed to see war, hunger, and poverty eradicated through collectivism… but not at the cost of spontaneity and freedom of choice. Their ancestors were right to invent a more equitable social order, the female revolutionist I-330 tells D-503. But afterward, she adds (speaking in a mathematics-inflected register intended to subvert D-503’s lifelong conditioning) “they believed that they were the final number — which doesn’t exist in the natural world, it just doesn’t.” Fun fact: We circulated in samizdat for years — in which form it influenced George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Reissued by Penguin Classics.

- Frigyes Karinthy’s Capillaria (1921). Gulliver, protagonist of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, who in Karinthy’s 1916 Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage (1916) visited a planet of intelligent machines, now finds himself saved from drowning in an underwater empire ruled by women. The males (“bullpops”) of this planet are fighters and builders, creative and rational… yet they are dominated by the emotional, illogical womenfolk. Not only do the women of Capillaria devote themselves entirely to pleasure, and tear down the (phallic) towers erected by the men, but they feed on the brains of their menfolk! A misogynistic adventure influenced by August Strindberg, who often made pronouncements like, “Woman, being small and foolish and therefore evil… should be suppressed, like barbarians and thieves.” Fun fact: Karinthy’s fifth and sixth journeys of Gulliver’s aren’t the earliest example of Gulliveriana — but they’re among the most influential.

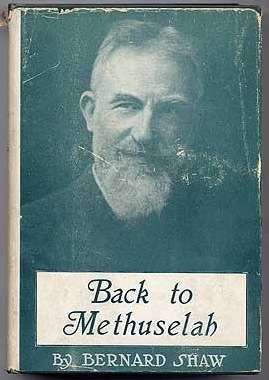

- George Bernard Shaw’s Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (1921). Shortly after WWI, the secret of Creative Evolution — in Shaw’s formulation, the process by which an organism can will its own entelechy, or self-potentiation — is discovered. By the year 3100 the long-lived elite have developed perfect physiques and advanced mentalities. Zozim and Zoo are Boomer-like superhumans (he’s nearly 100, she’s 50, but they act like young adults) who assist a sham oracle in overawing the short-livers seeking its advice. It’s all part of a plot to colonize and supersede ordinary humans! But like the proto-Yippies they are, Z and Z are upfront about the put-on. Zoo: “[Zozim] has to dress-up in a Druid’s robe, and put on a wig and a long false beard, to impress you silly people…. I have no patience with such mummery; but you expect it from us; so I suppose it must be kept up.” It’s Wild in the Streets meets Highlander. Fun fact: RFK was quoting this Radium Age sci-fi play when he said, “‘You see things; and you say, “Why?” But I dream things that never were; and I say, “Why not?”.’”

- Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist (1921). Having learned how to visit other worlds telepathically, Dr. Kinney and his companions enter the minds and share the sensations of the inhabitants of Hafen [Heaven], a planet inhabited by capitalists, and Holl [Hell], its twin planet, which is inhabited by workers. (Call it: psi-fi.) Not content merely to study the goings-on, Kinney & co. help the workers’ revolutionary party stop the Hafenites from invading a third planet Alma, which is inhabited by “‘cooperative democrats’; that is, they do not compete with each other for a living, but work together in all things, in complete equality.” Unfortunately, a Hafenite WMD separates the twin planets. This is the third occult-science-fiction Dr. Kinney story; the others are “The Lord of Death” (June 1919), “The Queen of Life” (August 1919), and “The Emancipatrix” (September 1921). Fun facts: Originally serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly (July 1921); also serialized here at HILOBROW by HiLoBooks. In 1965, Ace published The Devolutionist and The Emancipatrix together; could The Devolutionist and The Emancipatrix possibly be the best sci-fi title ever?

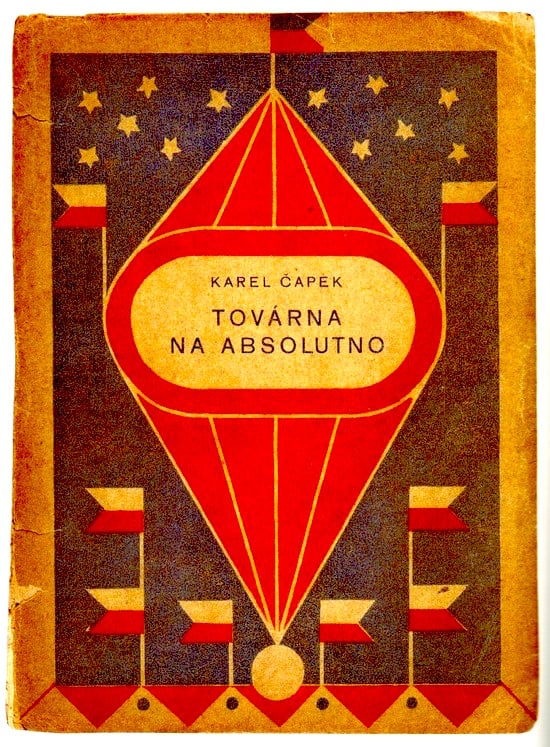

- Karel Čapek’s Továrna na absolutno (The Absolute at Large, 1922; in English, 1927). In the near future, a Czech scientist invents “perfect combustion,” and an industrial concern starts manufacturing an atomic reactor that provides cheap energy — with an unexpected byproduct: the Absolute, the spiritual essence that permeates every particle of matter… or did, anyway, until matter began to be annihilated by the super-efficient Karburetor. As they’re released from imprisoning matter by efficient Karburetors and Molecular Disintegration Dynamos cranked out in the thousands by Ford Motors (the novel’s Czech title means “the factory of the Absolute”) and other manufacturers around the world, God-particles infect humankind with wonder-working powers and ecstatic religious sentiments. What’s more, the Absolute begins operating factories itself, producing far too many finished goods for anyone to consume. As a result, economies collapse, unemployment is universal, and fanatical sects whose -isms (including rationalism, nationalism, and sentimentalism) are religious only in the broadest sense do battle. Every country is drawn into the Greatest War, during which atomic weapons are deployed and civilization collapses. Fun fact: Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

- Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (1922). When war breaks out in Europe, British civilization collapses overnight. The ironically named protagonist must learn to survive by his wits in a new Britain. When we first meet Savage, he is a complacent civil servant, primarily concerned with romancing his girlfriend. During the brief war, in which both sides use population displacement as a terrible strategic weapon, Savage must battle his fellow countrymen. He shacks up with an ignorant young woman in a forest hut — a kind of inverse Garden of Eden, where no one is happy. Eventually, he sets off in search of other survivors… only to discover a primitive society where science and technology have come to be regarded with superstitious awe and terror. Fun fact: Cicely Hamilton was an Anglo-Irish novelist, dramatist, and campaigner for women’s rights who served during WWI with an ambulance unit and at a military hospital in France. Her 1909 treatise Marriage as a Trade is a witty criticism of that institution. Reissued by HiLoBooks, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

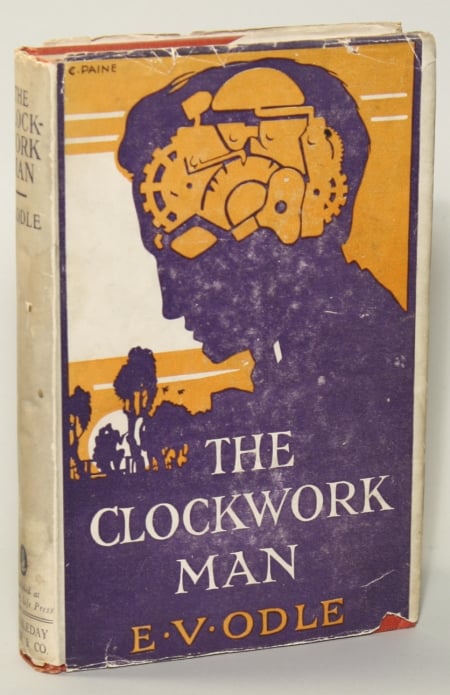

- E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man (1923). Years from now, advanced beings known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these marvelous devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live perfectly regulated lives. However, if one of these devices should ever go awry, a “clockwork man” from the future might turn up in the 1920s, perhaps at a cricket match in a small English village. Considered the original cyborg novel, and perhaps the original singularity novel too. “Odle’s ominous, droll, and unforgettable The Clockwork Man is a missing link between Lewis Carroll and John Sladek or Philip K. Dick,” says Jonathan Lethem. “Considered with them, it suggests an alternate lineage for SF, springing as much from G.K. Chesterton’s sensibility as from H.G. Wells’s.” Fun fact: Rumors that “E.V. Odle” was a pen name for Virginia Woolf are amusing, but unfounded. Edwin Vincent Odle (1890–1942) was a writer who lived in Bloomsbury, London during the 1910s. From 1925–35, he was editor of the British short-story magazine The Argosy. Reissued by HiLoBooks. with an Introduction by Annalee Newitz.

- J.J. Connington’s Nordenholt’s Million (1923). As denitrifying bacteria inimical to plant growth spread around the world, causing agricultural blight, Jack Flint is invited to become director of operations at a huge survivalist colony located in England’s Clyde Valley. Flint discovers that his employer, the ruthless plutocrat Nordenholt, has blackmailed the country’s politicians in order to establish his stronghold, of which he becomes dictator in all but name. What’s more, Nordenholt’s henchmen purposely wreck what remains of British civilization, leading to scenes of horrific mass violence and agony; and the colony’s workers are treated like serfs. The plant-killing plague ends… but Nordenholt’s collectivized serfs refuse to work, blow up the factories on which their fragile community depends, and join weird religious cults! The author, it seems, was as worried about the Soviet Revolution as he was about right-wing politicians and rapacious businessmen eager to use any disaster as an excuse to dispense with democracy, liberty, and justice. Fun fact: Connington was the pseudonym of Alfred Walter Stewart, the British chemist who coined the term isobar as complementary to isotope.

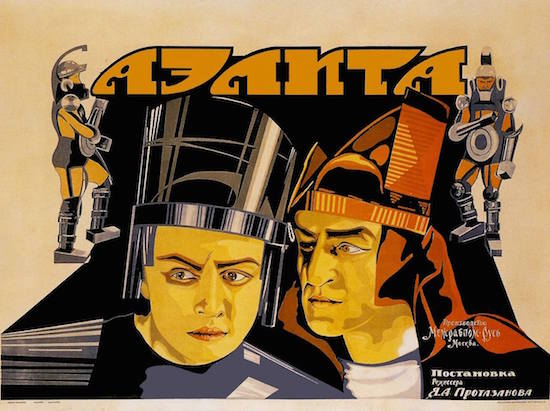

- Aleksey Tolstoy’s Aelita (1923). After the Russian Civil War (1918–1920), a lonely Soviet engineer, Mstislav Los’, and a retired soldier, Alexei Gusev, travel to Mars in a rocketship. It seems that Earthmen have been there before: the Martians they encounter are the descendants of Mars natives and Atlanteans! The class divide between workers — who live underground, near their machines — and the ruling class (the Engineers) is severe. Worse, the planet faces environmental catastrophe; the Engineers’ (Jor-El-esque) leader, Toscoob, plans to destroy their city, in order to save the planet. While Gusev helps lead a worker uprising against the Engineers, Los’ — who has fallen in love with Toscoob’s daughter Aelita, the princess of Mars — works to help her father crush the rebellion. Fun fact: Aleksey Tolstoy is credited with having produced some of the earliest works of Russian science fiction. Aelita was adapted, in 1924, as a far-out silent film directed by Yakov Protazanov.

For context, see my list of the Best Twenties Adventure.

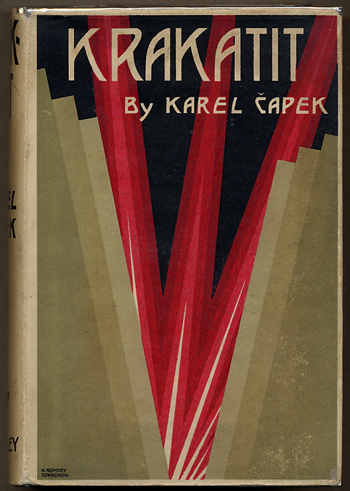

- Karel Čapek’s Krakatit (1924). When a Czech engineer, Prokop, invents an explosive which releases the destructive energy contained in atoms, and which can destroy entire cities, he is wooed and pursued by those — a wealthy munitions manufacturer, a beautiful anarchist, a villain who may be the Devil himself — who would control it. A dreamlike, absurdist, volatile admixture of romance, adventure, and philosophy, Krakatit warns that with technological advances comes unforeseen temptations and consequences. “Do you want to rule the world?” demands the villain, of Prokop. “Good. Do you want to annihilate the world? Good. Do you want to make the world happy by forcing upon it eternal peace, God, a new order, revolution, or something of the sort? Why not?” In the end, a horrific explosion occurs. Fun facts: Elsewhere, I have argued that this novel’s 1925 British dustjacket is one of the greatest Radium Age science fiction cover designs; it captures both the excitement and terror of breakthrough technology.

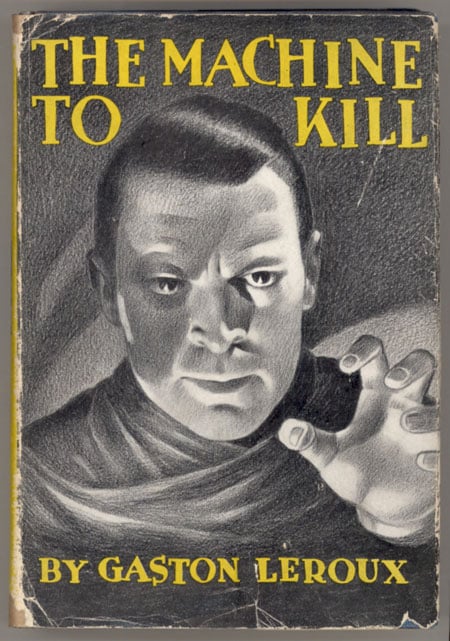

- Gaston Leroux’s The Machine to Kill (1924; in English, 1935). A human-looking mechanical man is animated by a clockwork expert (presciently named Norbert) with the aid of radioactive serum — oh, and the brain of guillotined murderer. The cyborg carries off Norbert’s daughter, only to later save her from… a Hindu vampire cult! Was the murderer innocent all along? France’s top police detective, Lebouc, investigates. Fun fact: Leroux is best known for his 1910 horror tale, Le Fantôme de l’Opéra.

- Upton Sinclair’s The Millennium (1924 edition). In 1907, Upton Sinclair wrote The Millennium, a comedic yet serious-minded play that looks forward to the year 2000 — at which point a “radiumite” explosion will kill everyone in the world except eleven people… who experiment with one sociopolitical system after another: Socialism, Communism, Capitalism, Feudalism, survivalism. Finally, three of the survivors — led by poor but resourceful Billy Kingdom — establish a utopian colony. In 1924, Sinclair rewrote the play as a novel. Fun fact: In 1906, Sinclair plowed the proceeds from his bestselling novel The Jungle into Helicon Home Colony, an artistic commune in New Jersey; it burned down in ’07. The utopian colony at the end of The Millennium bears a striking resemblance to Helicon.

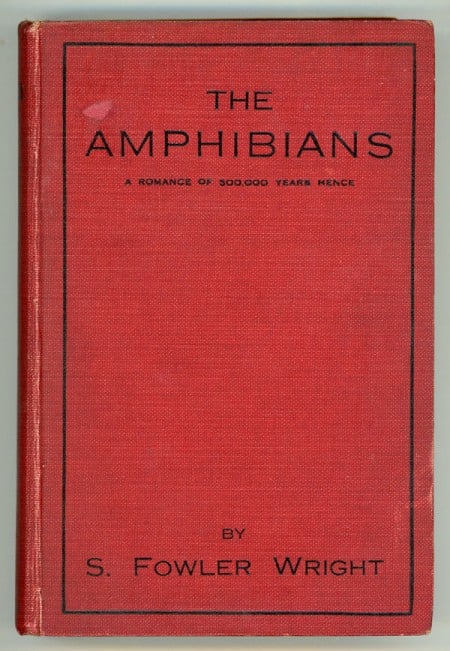

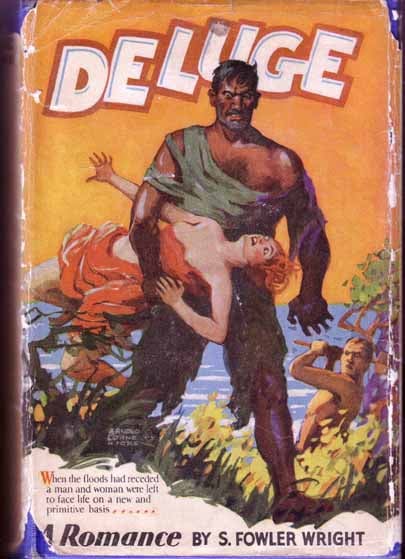

- S. Fowler Wright’s The Amphibians (1924–25). Half a million years in the future, a nameless, time-traveling human from more or less our era discovers that the Earth’s dominant intelligent species are now the giant Dwellers (humanoids self-destructively devoted to science) and the Amphibians (furry creatures who are morally more evolved than humans). Though he regards the [Kirk-like time] protagonist as an overly emotional primitive, a dispassionate [Spock-like] Amphibian accompanies him across a nightmarish landscape troubled by warfare between monstrous species; they debate philosophies of life and morality. Fun fact: Everett F. Bleiler calls The World Below (The Amphibians + its sequel, published together in ’29) “undoubtedly the major work of science fiction between the early Wells and the moderns.”

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Fatal Eggs (1925). In a near-future (or perhaps alternate-history) Moscow, the zoologist Persikov discovers a ray that causes frogs and other organisms to mature and reproduce at a rapid rate. At the same time, a disease wipes out all of Soviet Russia’s domesticated poultry. Persikov’s equipment is confiscated by the authorities, and thousands of chicken eggs are sent to his laboratory… so that the ray can be used to regenerate the country’s chicken population overnight. Unfortunately, a mixup causes snake and crocodile eggs, instead of chicken eggs, to be treated with the growth ray. Catastrophe! Fun fact: Some sci-fi exegetes suspect that Professor Vladimir Ipat’evich Persikov is a spoof on Soviet leader Vladimir Il’ich Lenin, i.e., who also unleashed destruction on Russia.

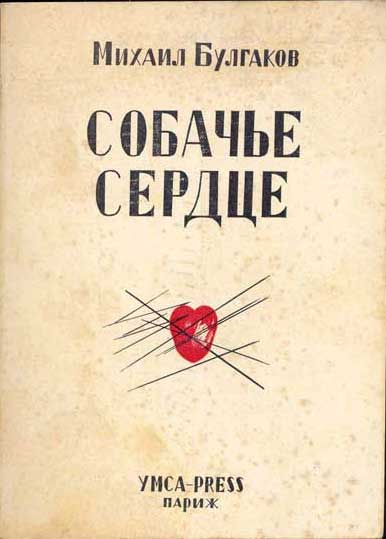

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog (1925). A comedic thriller that mostly takes place inside a Moscow apartment. Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky and his assistant, Dr. Bormenthal, implant the sexual organs and pituitary gland of an evil man into Sharik, a well-behaved dog. The scientists believe that they are imposing a progressive scientific system upon the Russian people; indeed, the resulting creature, a lout who calls himself “Sharikov” — succeeds all too easily in Soviet society. (Is Bulgakov’s story a satire on Communist attempts to create a New Soviet man? No doubt. But it’s also an homage to H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau.) How will Dr. Bormenthal deal with the problematic Sharikov? Firmly. Fun fact: Written in 1925, the book was considered critical of the Soviet state — so until after the fall of the USSR, it circulated in samizdat only.

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s The Navigators of Infinity (1925). Astronauts travel to Mars in the Stellarium, a spaceship made of “argine” (an indestructible, transparent material), and powered by artificial gravity. On Mars, the explorers come in contact with two races: the peaceful, six-eyed, three-legged “Tripèdes,” who have ceased to reproduce and are dying out; and the invading “Zoomorphs.” Having fallen in love (!) with one of the human astronauts, a young Martian female — merely by wishing it — gives birth to a child. This joyous event heralds the rebirth — City of Men-style — of the Martian race. Fun fact: Sci-fi scholars claim that Rosny aîné [Joseph Henri Honoré Boex, whose nom de plume contains the word “elder” (aîné) because he and his younger brother used to write together under the joint moniker J.-H. Rosny], author of the seminal 1909 prehistoric-fiction novel Quest for Fire, coined the word “astronautique” in this novel. Rosny aîné, who began writing in the 1880s, is considered the second-most important pioneer in French science fiction, after Jules Verne.

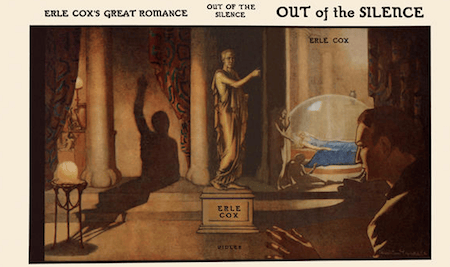

- Erle Cox’s Out of the Silence (1925). Having stumbled upon the subterranean repository of a long-vanished, fantastically advanced civilization, Alan Dundas awakens a beautiful woman from a state of suspended animation. Earani’s amazing intelligence and abilities are the end result of her civilization’s worldwide eugenics program, which she intends to put back into practice, as soon as she conquers the planet. “This world of yours is full of pain and misery… Is any price too great that buys a perfect and wholesome humanity?” Earani demands of Australia’s prime minister. “You hold that to carry out my mission would be a crime. I hold that to fail in doing so would be a crime.” (Alan, who falls in love with Earani, is undisturbed by her plan to wipe out the “colored races” and inferior whites; one is not sure what the author himself thinks about this subject.) David Bowie’s synopsis: “Here she comes, here she comes again/The same old painted lady/From the brow of the superbrain/She’ll scratch this world to pieces/As she comes on like a friend.”

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Maid (1926). A sprawling saga that gallops from Julian 5th’s crash-landing on the moon, where he makes a daring getaway (with a moon maid in tow) from subhuman Kalkars who dwell in the asteroid’s hollow interior; to the same Julian’s doomed effort to defeat a Kalkar invasion of Earth; to Julian 9th’s failed but inspiring rebellion against the mongrel descendants of the Moon Men, communistic tyrants who’ve presided over the Earthlings’ regression to a medieval agrarian lifestyle; to the final triumph of Red Hawk (Julian 20th), the leader of a primitive tribe of freedom-fighters — who, 400 years after the invasion, defeats humankind’s overlords in a pitched battle set in the ruins of Los Angeles. Fun fact: The Julian 9th story, one hears, was originally written after the Bolshevik revolution, and was rejiggered later to fit into the Moon Maid saga. Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.