A Sense of Doubt blog post #2271 - I wrote a story! Submitted to Dangerous Visions Volume Three

I wrote a story in a month and submitted it to Dangerous Visions, VOLUME THREE also known as The Last Dangerous Visions.

The first two Dangerous Visions volumes were produced and edited by the late, great Harlan Ellison.

The deal for this submission is it only applied to writers who have never been paid in money for their fiction. I can confidently say that this is a true thing about me.

The most important thing is that from the time I hear of this submission option to the time I started writing the story to finishing the story was much less than a month.

My story is called "The Spangle Maker." Here's a summary:

Driven into sealed habitats by a pandemic, TexAmerica restricted the population to keep it great: whites & straights only. All others were exiled. When true patriots forget the National Anthem, Neko HaffBrunner finds that one man can get him exiled for his hate crimes.

Since the story is under consideration, I am not going to publish it here, though I doubt anyone would notice.

J. Michael Straczynski (JMS)

https://www.patreon.com/m/4412429/posts

I wanted to post the solicitation text JMS wrote for the story slot for which I submitted, but I was too slow, and he has taken down the text.

Instead, here's some information on Dangerous Visions AND even one article on this new volume.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/nov/16/harlan-ellison-the-last-dangerous-visions-anthology-may-be-published

Harlan Ellison's The Last Dangerous Visions may finally be published, after five-decade wait

Sci-fi anthology stalled since 1974 will be produced by executor, screenwriter J Michael Straczynski, adding stories by today’s big-name SF writers

|

| Combative nature … Harlan Ellison, pictured in 1977. Photograph: Barbara Alper/Getty Images |

It is the great white whale of science fiction: an anthology of stories by some of the genre’s greatest names, collected in the early 1970s by Harlan Ellison yet mysteriously never published. But almost 50 years after it was first announced, The Last Dangerous Visions is finally set to see the light of day.

The late Ellison changed the face of sci-fi with the publication of anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again, Dangerous Visions, in 1968 and 1972, which featured writing by the likes of Philip K Dick, JG Ballard, Kurt Vonnegut and Ursula K Le Guin. Ellison, who was known for his combative nature – JG Ballard called him “an aggressive and restless extrovert who conducts life at a shout and his fiction at a scream” – announced a third volume, The Last Dangerous Visions, would be published in 1974. Contributors were said to include major names such as Frank Herbert, Anne McCaffrey, Octavia Butler and Daniel Keyes.

But the work never appeared, and in the words of the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, it “became legendary for its many postponements”. The encyclopedia notes that “a series of illnesses certainly impaired Ellison’s fitness for the huge task of annotating what had soon become an enormous project”; in their study of Ellison, The Edge of Forever, Ellen Weil and Gary K Wolfe say the anthology ran to over a million words.

The encyclopedia also points to “the moral dilemmas [Ellison] incurred by retaining purchased but unpublished stories – eventually in some cases … for close on 50 years” – a delay that so riled author Christopher Priest that he wrote and self-published a lengthy, scathing analysis titled The Last Deadloss Visions.

Now, television screenwriter J Michael Straczynski, who was appointed executor of Ellison’s estate after his death and that of his wife Susan earlier this year, has launched a Patreon account, where fans can pay to take part in the book’s publication process.

Straczynski is planning to include dozens of the stories originally commissioned by Ellison, as well as work by “some of the most well-known and respected writers working today”, who are yet to be revealed. It will also feature “one last, significant work by Harlan that has never been published, that has been seen by only a handful of people”, and will reveal why the book was delayed for so long, “a story known only to a very few people”.

“Rather than seeking a publisher first, and potentially compromise a book designed to be challenging and daring, or asking writers to wait until the book is sold to be paid, I will cover the cost of paying for all of the stories up front,” he wrote.

Straczynski plans to sell the book to a publisher next year, saying that several “major” presses have already expressed “significant” interest, “given the unique place in science fiction history occupied by Dangerous Visions in general, and this book in particular”. All royalties are set to go to the creation of the Harlan and Susan Ellison Memorial Library, in their home in California.

“It starts right here, right now, today,” Straczynski wrote. “After 46 years of anticipation, we are finally bringing this beast in for a landing.”

|

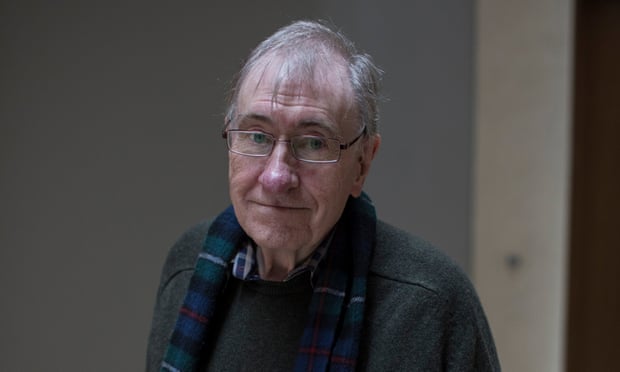

| ‘A lot of the writers have disowned their stories as juvenilia’ … novelist Christopher Priest. Photograph: David Levenson/Getty Images |

Contacted by the Guardian on Monday, Priest was unimpressed, saying that Straczynski was “in the same sort of unenviable position as Trump’s caddie”.

“I kind of lost interest in all that years ago. Ellison clearly did too, along with everyone else. (Although I gather he went on with his magical thinking if anyone asked when he was going to deliver),” he wrote. “Many of the stories were withdrawn, because Ellison acted like a dick. Of the ones that remain, most of them are by writers who are now deceased, so the rights have expired and the estates would have to be traced. A lot of the writers have disowned their stories as juvenilia, or outdated, or simply because Ellison was acting like a dick.”

But, Priest added: “Mr Straczynski is an experienced professional, so maybe he’ll work something out.”

A Look Back at Harlan Ellison's Dangerous Visions (1967)

by Ted Gioia

Almost every aspect of Harlan Ellison's 1967 anthology of science

fiction tales, Dangerous Visions, disrupted the status quo. Unlike

other anthologists, Ellison insisted on brand new stories for his book

—in stark contrast to the time-honored tradition of collecting works

that had already appeared in magazines. This proviso created, in

turn, economic disruption for both Ellison

and the publisher, because they had to

pay more for new stories than for recycled

ones. Ellison was even more daring in his

choice of contributors, aiming to bring in

both leading literary heroes of avant-garde

fiction, famous genre writers and the very

best of the up-and-coming sci-fi authors.

But the most disruptive aspect of the project

came with the instructions Ellison gave his

contributors. He really wanted dangerous

visions, stories that broached themes and

subjects too hot for the science fiction

magazines of the day. He insisted that

the tales in the book confront taboos, break

down barriers and challenge prevailing attitudes and values.

advance from his publisher, and was forced to draw on his own money

to pay his authors. One of the contributors, Larry Niven did the same,

lending $750 to cover some of the publication costs. Ellison also ran

into obstacles in his choice of writers. He successfully enlisted many of

the best science fiction authors of his day for his project, but his hopes

of snagging the leading literary lions from the counterculture proved

ill-founded.

His initial list of possible contributors included Thomas Pynchon, William

Burroughs, Terry Southern, Kingsley Amis and Thomas Berger. The mind

reels at how they would have responded to Ellison's request for dangerous

visions. But none of these writers participated in the project. I lament their

absence, but still can’t find fault with a final roster that includes Philip K. Dick,

J.G. Ballard, Samuel R. Delany, Theodore Sturgeon, Brian Aldiss, Robert

Silverberg, Roger Zelazny, Fritz Leiber and Robert Bloch, as well as an

introduction from Isaac Asimov (who refused to offer a story on the grounds

that he was "too sober, too respectable, and, to put it bluntly, too darned

square").

Ellison lived up to his promise of violating taboos. I suspect that this

willingness to offend, and risk the opprobrium of censors and the

censorious, created much of the buzz around the book. Certainly

sales were brisk. Dangerous Visions has stayed in print, and also

spurred a high-profile sequel (Again, Dangerous Visions), as well

as a proposed third volume slated for release in 1973, but still

in publishing limbo. (A few years ago, Jo Walton reviewed this

oft-discussed but never-seen anthology, The Last Dangerous

Visions, as an April Fool's Day joke. As recently as 2007, Ellison

was still claiming that he wanted to publish the work, but griping:

"It’s this giant Sisyphean rock that I have to keep rolling up a hill,

and people will not stop bugging me about it.")

Strange to say, the dangerous parts of Dangerous Visions have not

aged especially well. It's hard to find anything shocking nowadays, not

just in fiction but in any other form of narrative. And the few taboos that

survived into the modern age are just as predictable as moral injunctions

—no surprise there, since they are mirror image of each other—and

readers can easily guess which subjects will show up even before they

open this book. So we get a big dose of cannibalism, a smattering of

incest, lots of sexual experimentation and kinky fetishes, some serial

killers, etc. etc.. In other words, the usual suspects when people are

asked to violate the inviolable. Alas, if this were enough to create great

literature, Jerry Springer would be a Nobel judge.

That said, a few contributors stood out for the very vehemence with

which they pursued the transgressive. Ellison’s single story in the

volume, a futuristic reworking of the Jack the Ripper meme, presents

more vivisection details than a coroner’s report. And Theodore Sturgeon

not only serves up a story about incest, but offers a spirited treatise

in defense of the same. Even Robert Heinlein, who put his hero

Lazarus Long on a time machine so the character could have an affair

with his own mom, never went quite so far.

Some of the finest stories in this book ignored Ellison's mandate

to embrace 'dangerous' visions, and succeed through plain old-

fashioned storytelling. J.G. Ballard and Fritz Leiber both contributed

atmospheric horror stories. Ballard's reticence is especially surprising,

given the outrageous and repulsive subjects in his other works of this

period. Yet his tale of a traveling circus that arrives in town with cages

for the animals, but apparently no creatures inside them, is darkly poetic,

and saves a pleasing Kafkaesque twist for its conclusion. Leiber's

contribution is a macabre fairy tale about a gambler getting into a

high stakes dice game with the grim reaper. The story is unsettling,

but more in the manner of Ambrose Bierce than New Wave sci-fi—

and with a pleasing dose of Leiber's trademark flippancy and

irreverence. I’m not surprised that it won the Hugo for best novelette.

Ellison makes a big deal about Philip K. Dick’s 'dangerous vision'

—and hints that the story was written under the influence of a

hallucinogenic drug. Frankly, I’m not sure I could tell the difference

between Dick’s output on drugs and the stories he wrote cold-sober.

They all are pleasingly weird. But "Faith of Our Fathers," his

contribution to Ellison's anthology, is one of his best—it also earned

a Hugo nomination (losing out to Leiber's story). Narcotics do play

a prominent role in the plot, but with an ingenious twist: in Dick's

universe, the citizenry all experience the exact same hallucinations

when drugged, but while they are clear-headed, their perceptions of

reality vary in inexplicable ways. Dick takes this provocative concept

and incorporates it into a dystopian account of space aliens and

global conquest straight out of the Golden Age of sci-fi.

Perhaps the most famous story in this book is also the longest. Philip

José Farmer's "The Riders of the Purple Wage" was initially a 15,000-

word tale, but after he had finished revisions, it had expanded into a

rambling 30,000 word short novel. Ellison lavishly praised the work

in his introduction, claiming that it was "easily the best" piece in the

anthology. Certainly, many others agreed. Farmer also got a Hugo

for his efforts—part of the Dangerous Visions landslide victory at the

26th World Science Fiction Convention in Berkeley. This Joycean

pastiche is certainly one of the most audacious pieces in the collection,

both for its prose style and the copious amounts of sex and violence

in its plot. But the story constantly hints at more than it actually delivers.

Farmer lays out the foundations for a penetrating satire of politics, art

and culture, yet never pursues any of these promising paths with much

vigor. And instead of moving towards a resolution of the plot, he merely

builds up to a huge pun—one so over-the-top that even Joyce, that

master punster, would have groaned in dismay at it.

Now, I must turn to the biggest surprise of this book—namely that many

of the most impressive stories in Dangerous Visions came from

little-known and mostly-forgotten authors. "The Doll-House" written

by James Cross—a pseudonym for career academic and government

worker Hugh Parry (1916-1997)—presents a very appealing mixture

of ancient mythology and modern psychodrama. But just try to find more

information about this author, even with the help of all-knowing Google!

I also enjoyed stories by Larry Eisenberg and Jonathan Brand, stylish

authors who never achieved much fame but proved their mettle in this

anthology. But best of all is David R. Bunch, the only writer to contribute

two stories to Dangerous Visions. These are, in my opinion, the most

ambitious and well-written stories in the whole book, drawing on a

poised but unconventional prose style that is not a pastiche, in the style

of Farmer’s piece, but a brilliant reconfiguration of language perfectly

suited to avant-garde science fiction. Bunch’s work is like a blend of

Flann O’Brien and Italo Calvino, leavened with the technology acumen

of Isaac Asimov. I was saddened to learn that this author’s writings

went out-of-print soon after they were published, and now command

outrageous prices for tattered old paperback copies. Some enterprising

publisher needs to rectify this situation!

But the star of Dangerous Visions remains Harlan Ellison, and though

he contributed just a single story, his introductions to the book and each

of the tales are what set this work apart from the other anthologies in the

field. In a different time and place, Ellison might have written suppressed

political manifestos, screeds that would have set off rioting in the

streets and the toppling of regimes. Instead, he aimed at spurring a

revolution in fiction, with an inflammatory zeal that no one else of his

generation could match. He often took more risks in his intros to the

stories than the authors did in their narratives, and I can only imagine

how much behind-the-scenes prodding and nagging he devoted to

making this cantankerous book, and its sequel, a reality. Ellison clearly

possessed dangerous visions, and it is to his credit that he was able

to get a whole cadre of sci-fi legends, near-legends, and should-be-

legends to march to his beat. A half-century later, when the forbidden

topics in this book are no longer prohibited and more than a few have

entered the mainstream, Ellison's strident stances and extravagant

expostulations can still captivate readers. So even if the dangers

embodied in Dangerous Visions today seems less perilous, let's give

some of the credit for that sea change to the visionary behind the visions,

who helped tame them for posterity.

working on his ninth book, Love Songs: The Hidden History, which will be

published by Oxford University Press.

Publication date of this article: May 21, 2014

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2105.07 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2135 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment