A Sense of Doubt blog post #3351 - SPEEDY: That One Time with the Drugs: Comic Book Sunday for 2404.21

This post has been in the works for a while and is one of two as I plan to present equal time to the way Marvel addressed the "drug problem" in 1971, which actually preceded this DC version.

I have always been fascinated by these comics about drugs, especially given the rumors in fandom -- which I cannot confirm -- that Speedy was originally to be shown literally with the needle in his arm on the cover and that was a bridge too far for the publishers, and so the compromise was the cover above.

https://50yearoldcomics.com/2021/06/26/green-lantern-85-aug-sep-1971/

I chose to feature the next issue in this post and the overall issue of Speedy's two-issue drug addiction that resolved between issues of Teen Titans and was only mentioned in one panel (featured far down this post).

Green Lantern #86 (Oct.-Nov., 1971)

There’s a lot going on on the cover of Green Lantern #86. Besides boasting an outstanding illustration by Neal Adams that would probably be even better remembered than it is if it hadn’t followed right on the heels of its instantly iconic predecessor, the cover also boldly heralds the inclusion within the comic’s pages of “an important message” from no less a personage than the 1966-73 mayor of New York City, John Lindsay — and proudly announces that Green Lantern has won the Academy Award for Best Comic. That’s a lot to take in — but don’t worry, we’ll get to it all, starting with the subject of Adams’ compelling cover image — the concluding installment of the groundbreaking two-part story focused on drug addiction that Adams and writer Denny O’Neil had begun in the previous issue, #85.

Here’s hoping that you read our post about that landmark issue back in June, because we’re going to jump right into #86 sans recap, just like O’Neil and Adams (aided and abetted by returning inker Dick Giordano) did half a century ago. But if you missed that piece — or would simply like to refresh your memory — just click on the link above, and take a few minutes to catch yourself up. Don’t worry, we’ll wait.

All done? All right, then, here we go…

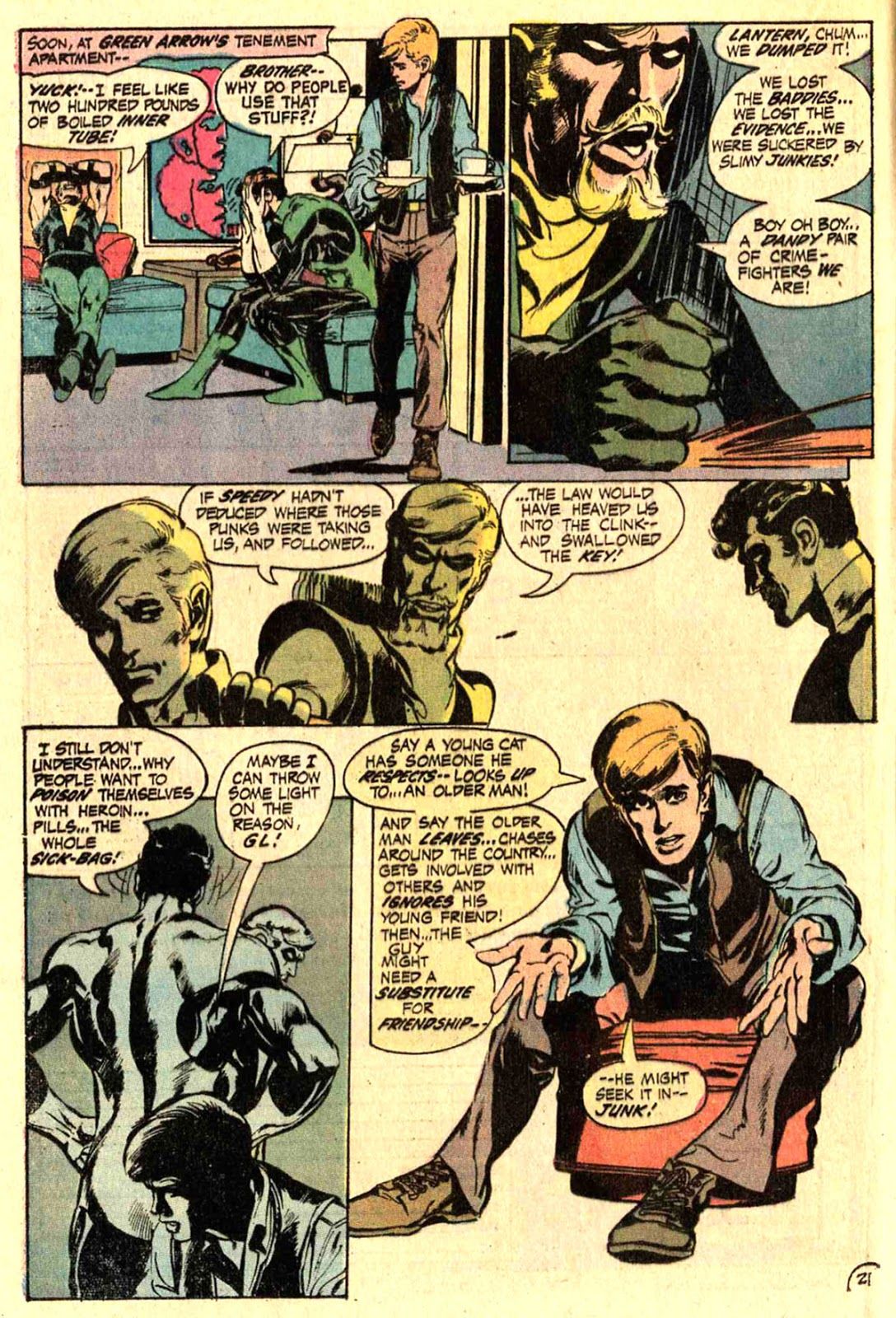

The storytelling’s a little iffy, here, as the previous installment had given us no reason to believe that Speedy’s buddies (who never receive names, incidentally) have any idea that he lives in GA’s apartment (nor, come to think of it, have we readers been expressly told that he does, up until now). But we’ll let that go. What’s actually more interesting (to your humble blogger, at least) is that the two young addicts know their friend by his superhero moniker Speedy, and not by his actual civilian name of Roy Harper. Granted, “Speedy” is easier to pass off as an ordinary nickname than, say, “Green Arrow”, but presumably it’s still relatively well-known in the two archer-heroes’ home base of Star City. It’s hard to believe that Roy would throw it around casually when he’s out of costume, no matter how strung out he might be at the time.

Discussing these two Green Lantern issues in a 1975 interview for Amazing World of DC Comics #4, Denny O’Neil observed: “We got a lot of negative reaction because we made a long-standing superhero an addict: Speedy. Sorry about the name, but there it was folks — I didn’t make it up. ” Well, maybe not, but O’Neil certainly did utilize the name — which, in the current context, is obviously suggestive of amphetamine use — at every opportunity throughout his story. Every single character consistently refers to Roy as “Speedy” (as does the third-person omniscient narrator), despite the fact that the closest Roy ever gets to suiting up in the ol’ red-and-yellow in either issue is on #85’s cover. I’d actually suspect that O’Neil didn’t even know that Speedy had another name — except that “Roy” does get used a total of two times, both very near the story’s end. As things stand, I think it’s anyone’s guess as to whether or not O’Neil really was intentionally playing up the drug-related associations of Roy Harper’s heroic appellation,.

But, to return to our narrative… Finding Roy’s discarded “works” on the floor, the two addicts decide that they might as well take the opportunity to shoot up right then and there, using the heroin they received in the last chapter as a reward for helping entrap our two Emerald Crusaders. Uncertain exactly how much of the drug should be includes in a single dose (“I’m not used to fixin’ pure stuff! Usually it’s cut!”), the Asian-American youth makes his best guess:

Admittedly, pretty much everything I know about the decomposition of corpses comes from entertainment media, but an hour or two seems too early for a dead body to start to smell of decay, at least enough for it to be detected by us ordinary humans. Maybe GL’s habitual use of his power ring has somehow had the side effect of granting him a preternaturally keen sense of smell, like a crime-sniffing dog? Sure, let’s go with that.

As Green Lantern once again flies off into the night, this time to search for Green Arrow and Speedy, GA himself arrives at the airfield hanger where he and GL were waylaid earlier that evening…

We’d heard from Oliver in the opening scene of GL #85 that he and Dinah (Black Canary) Lance had had a big fight and presumably broken up; neither of the characters makes any mention of such problems in this issue, however, so perhaps Ollie was overreacting.

Arriving at the marina pier he was directed to by the hood at the airfield, Green Arrow finds that the only boat docked there is an enormous yacht. He suspects he may have been given a bum lead; but before he can do anything about it, he’s jumped by the same two dope dealers whom he and Green Lantern confronted in #85:

In the same Amazing World of DC Comics interview we referenced earlier, Denny O’Neil noted:

…there was one point that we were trying to be subtle about, and we were so subtle nobody saw it. In the cocktail party scene we implied a condemnation of alcohol addiction, too, but nobody evidently paid much attention to that.

The boat carrying Saloman and his guests quickly departs from shore, heading for a fun-in-the-sun weekend on the Caribbean which, in reality, is a cover for heroin smuggling — as we learn from some expository dialogue delivered by the two hoods who’ve been left behind on the pier to dispose of Green Arrow. Speaking of which….

This near-wordless sequence is a prime example of another of Neal Adams’ trademark visual storytelling devices; for me, it’s also always been the most memorable scene in the whole issue.

Out in the Caribbean sea, Saloman takes temporary leave of his partying guests; sailing to a nearby shore via a small motorboat, he proceeds from there to the local offices of Hooper Pharmaceuticals, Inc….

Having Green Lantern be the member of the duo who goes a little crazy on the bad guy, and Green Arrow the one who cautions restraint, is an obvious reversal of how things usually work in this series; I believe it’s intended to underscore the impact that the events of this story have had on GL, who was depicted as being painfully naïve about drugs in the beginning.

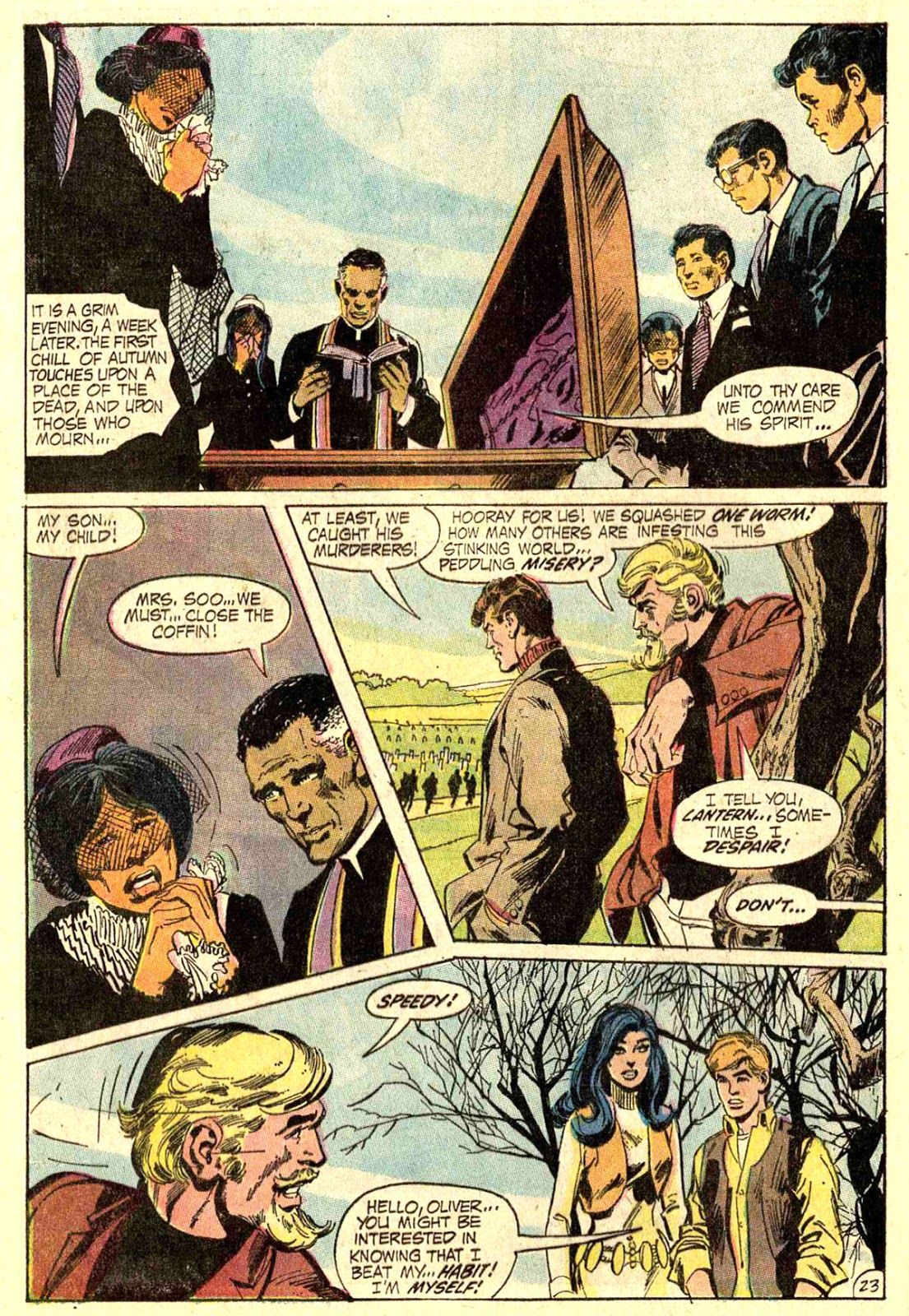

The story moves forward a week in time for its closing scene, which takes place at the funeral of Roy’s late friend, the young man who overdosed on page 4…

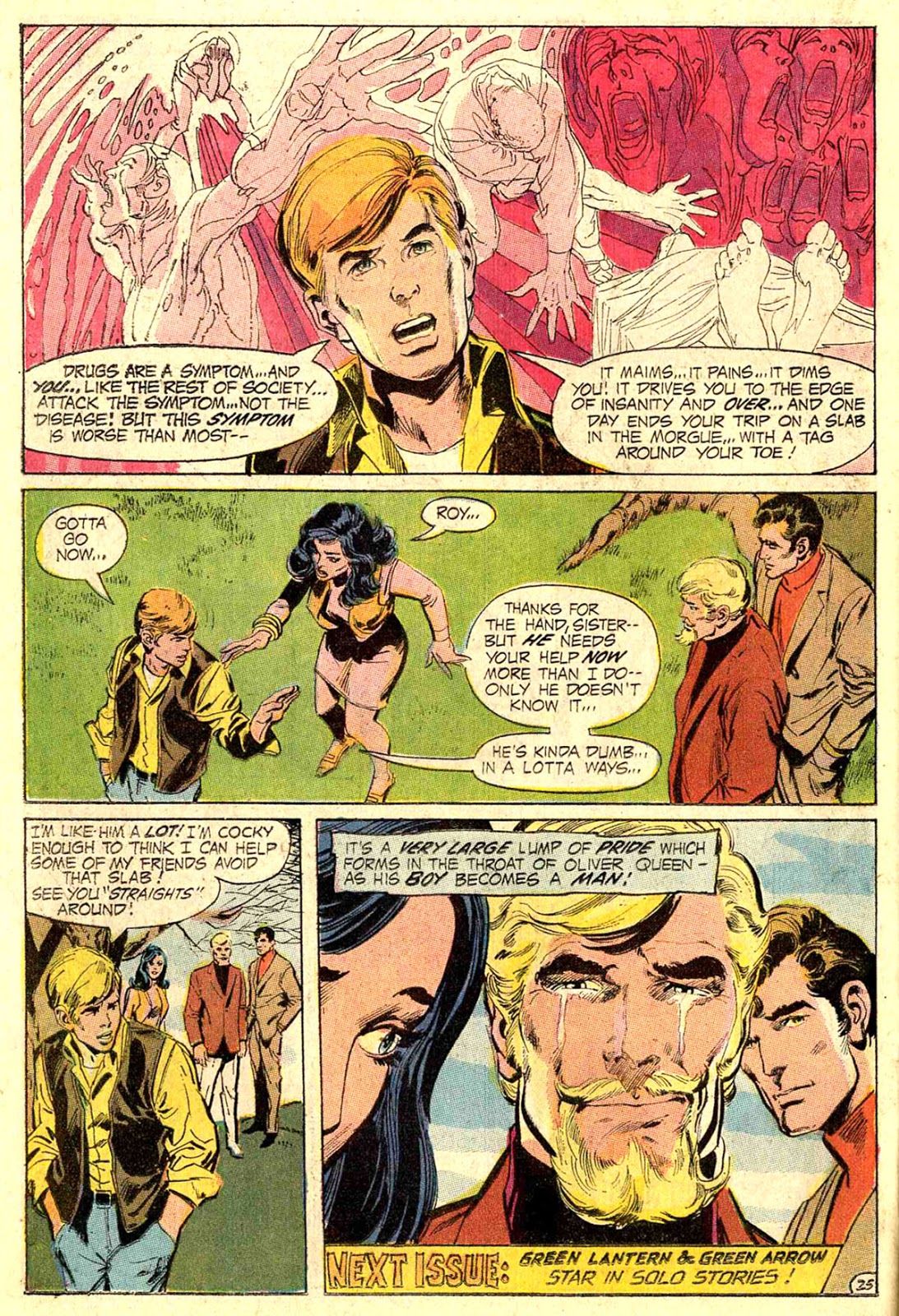

I’m sure you noticed that Speedy finally gets called by his given name on these last two pages — and I believe it’s significant that the two people who use the name are Hal and Dinah, the two adults that Roy calls his friends, and whose behavior he contrasts to that of Oliver, his supposed father figure.

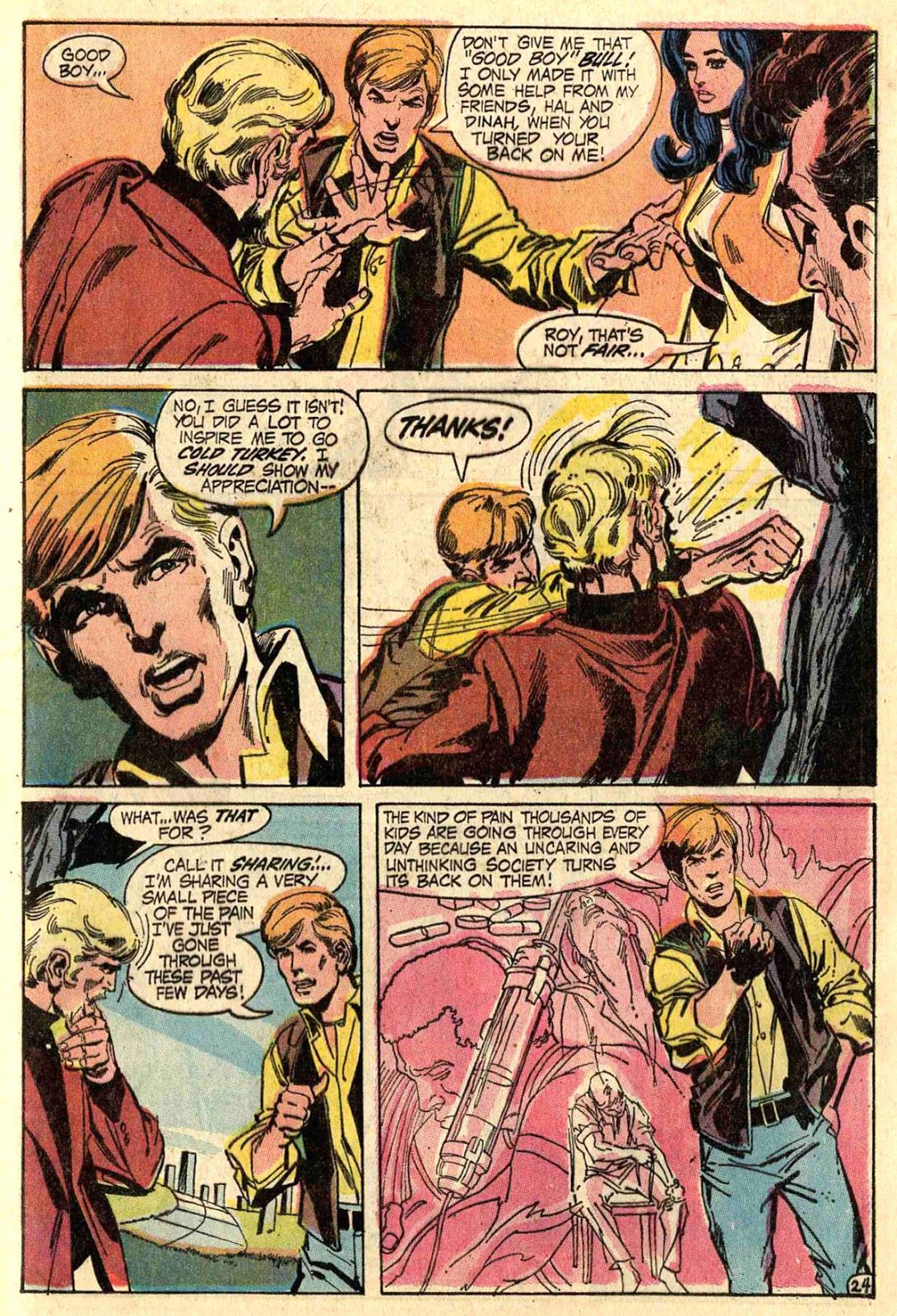

Interestingly, quite a bit of what happens in this final scene — including Roy’s punching Oliver — was evidently not in O’Neil’s original script. In response to a question about the ending in his Amazing World of DC Comics interview, the writer said:

Well… it’s not exactly as I wrote it. Let it charitably go at that. And it was not changed by the editor, or the publisher.

I disapprove of the implied conclusion of that story. What’s implied is that a punch in the mouth solves everything.

Neal Adams gave his side of the story in a 1996 interview for Comic Book Marketplace #40:

The script, as originally written, has Speedy basically telling GA he beat the habit by himself. GA says, “Good boy,” and they walk off together.

I read this and thought, no … what has changed? Somebody had to learn something. GA had to learn some kind of lesson. He had to learn to respect this person that he had beat up at the beginning of the story. I felt the strongest possible climax was necessary, considering how we started the story. I made my feeling perfectly clear to Denny, that I thought his ending was anti-climactic, but he let me know, basically, it was fine as is.

Well, I thought it was important enough to bring it up to the editor, so I wrote two extra pages where Speedy punches GA back, lets him in on his pain, and then splits.* GA, the father figure, knows the kid’s right and realizes that he [GA] was an ass. This ending made all the sense in the world to me. I brought the pages to [editor] Julie [Schwartz] and said, “I honestly think this is how the story ought to end.” He read them and said to go ahead and do it.

I can see both sides, honestly. On the one hand, the original ending, as described by Adams, does sound rather anti-climactic, in that it seems to let Oliver off the hook a little too easily. On the other hand, I sympathize with O’Neil’s objection to the implied message in Adams’ revised version that “a punch in the mouth solves everything” — though I also have to acknowledge the irony of that statement in the context of discussing a comic book story in the superhero genre, where the quoted principle is often literally true. In the end, it’s regrettable that the two creators weren’t able to work out a compromise that satisfied them both before the book went to press — perhaps Roy could have read Oliver the riot act without slugging him? — but the ending we have is the one we have to judge, obviously, and as imperfect as it may be, I believe it holds up pretty well.

One thing that both endings evidently had in common is Roy’s getting clean and walking off — maybe into the sunset, and maybe not, but definitely into the next issue of Teen Titans –which would have been #36, released in September, 1971. Right?

Well, maybe not. In 1971, DC still didn’t evince much concern with line-wide continuity, as a rule; certainly, there was no company policy mandating it. For that reason, I suspect that none of the members of the creative team behind GL #85 and 86 — including editor Julius Schwartz — consulted with either the current writer on Titans, Bob Haney, or the book’s editor, Murray Boltinoff, regarding the plan to put one of that series’ headliners through a drug addiction storyline. And even if they did, Haney and Boltinoff evidently ignored them (just as they tended to ignore other writers’ and editors’ stories in other books they worked on together, such as Brave and the Bold and World’s Finest). From issue #36 on to the end of the original run of Teen Titans — which came with #43, published in November, 1972 — there was no mention whatsoever of Roy Harper’s recent travails.

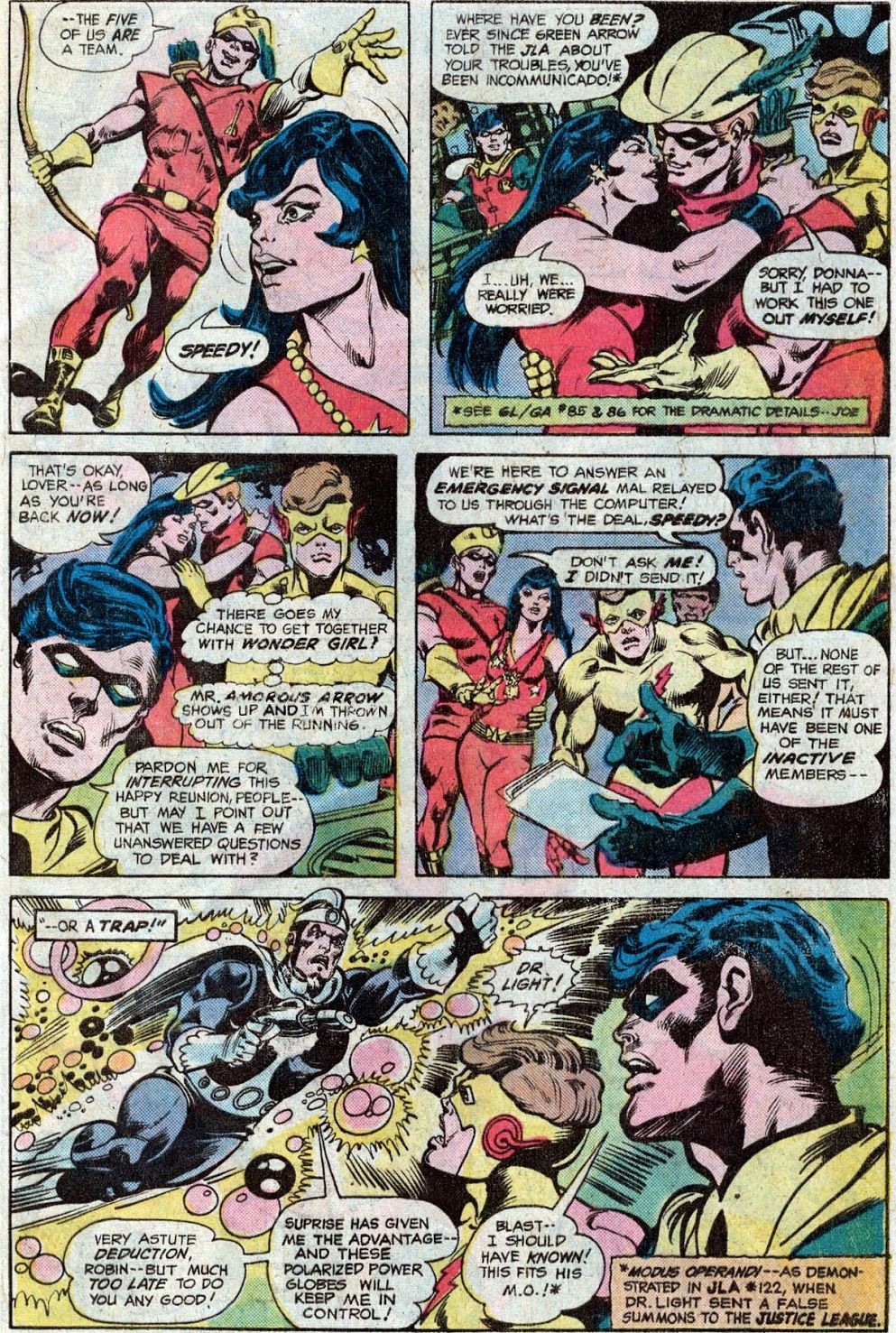

In 1976, however, DC revived Teen Titans — and at least some members of the title’s new creative team (which included fans-turned-pro writers Paul Levitz and Bob Rozakis) had somewhat more concern for continuity, even if the company as a whole remained noncommittal on the subject. And so we got a scene referencing Speedy’s drug problem, which clearly indicated that the relevant events in Green Lantern had taken place after TT #43, despite having been published a year and a half earlier.

Since then, of course, Roy Harper’s history of addiction has been a fundamental part of his backstory, surviving through DC’s myriad of retcons and reboots. In the hands of skilled writers, it’s added depth to his characterization, and allowed for sensitive treatment of the theme of living in recovery. (Unfortunately, not every writer who’s taken up the topic has been equally skilled in handling it; but that’s a whole ‘nother topic.)

Moving on from GL #86’s lead story to one of the other matters promoted on the cover: DC couldn’t wait to share the news of Green Lantern‘s success at the very first awards ceremony held by the Academy of Comic Book Arts (ACBA) — and while they evidently couldn’t spare the space for the full-page house ad (illustrated by Neal Adams) that ran in some other late-August DC comics, which honored the company’s full slate of winners, a goodly portion of the real estate of this issue’s letters column was devoted to GL‘s triumphs:

We’ll have more to say about these awards next month — for now, I’ll just note that while the ceremony wasn’t a complete sweep for DC, it came pretty damn close.

And now, the Honorable John V. Lindsay, Mayor, New York City:

If the name Marc “Iggy” Iglesias rings a bell, it may be because you read our blog post about Green Lantern #84 a few months back. There, we discussed how Mr. Iglesias, an executive who’d arrived at DC in the wake of the company coming under new corporate ownership in 1967, allowed his likeness to be used for the character “Mayor Dr. Wilbur Palm” (a disguised alias of the villain Black Hand), to the extent that his actual photo was used on the cover.

The only other observation I have to make about Hizzoner’s letter is that despite the way DC frames it here — “An Important Message for YOU!” — none of its content is actually addressed to this comic book’s readers. Rather, the bulk of it is directed to DC’s representative Iglesias, congratulating the company on making this effort. Even the indented section, framed by Lindsay himself as his message to “young people”, discusses those very young people in the third person. It’s almost as though the mayor had no idea what to say to Green Lantern‘s audience beyond “drugs are bad”.

In retrospect, I guess we should be grateful that Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams had a few ideas to convey beyond that simple sentiment.

For the first “bigger & better” 25-cent issue of Green Lantern, Julius Schwartz had reprinted a story from Hal Jordan’s early Silver Age years. For the second, he reached quite a bit further back into the DC archives:

“The Icicle Goes South”, written by Robert Kanigher and illustrated by Alex Toth, was, if I’m not mistaken, the first original Golden Age Green Lantern story I’d ever seen. As such, my fourteen-year-old self probably found it an interesting curiosity, but little more than that, Today, I’m better able to appreciate the tale’s charms, especially the very early art by Toth (uncredited here, and I’m sure unrecognizable to me in 1971 as being by the same guy who’d much more recently drawn a number of horror-mystery stories in House of Mystery, Witching Hour, and Eerie that I’d thoroughly enjoyed) — though, if I’m going to be honest, it still seems at least a little incongruous to me, sitting just a few pages over from “They Say It’ll Kill Me… But They Won’t Say When!” Others, I’m sure, find it a nice palate cleanser after the heavy drama of that story, and that’s just fine. (To each their own, and all that.)

*I just realized that if we take Adams’ statement that he “wrote [the] two extra pages” that end the story literally, it implies that he, rather than O’Neil, was the one who finally used the name “Roy” to refer to Speedy. Hmm…

Speedy's Entire Drug Problem Occurred Between Issues of Teen Titans

In "Our Lives Together," I spotlight some of the more interesting examples of shared comic book universes. You know, crossovers that aren't exactly crossovers.

This is a bit different from my typical editions of Our Lives Together, as this one is an interesting example of how POORLY two titles interacted with each other in a shared continuity.

As you likely know by now, Green Lantern #85 (by Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams) revealed that Roy Harper, Speedy of the Teen Titans and Green Arrow's ward and sidekick, was addicted to heroin...

Black Canary helps Roy through basically going cold turkey, as Green Arrow wants nothing to do with him...

He then tells off Green Arrow at the end of the issue...

The problem is that NONE of this was addressed in any of the then-current issues of the Teen Titans (mostly written by Bob Haney, art by Nick Cardy and a few others).

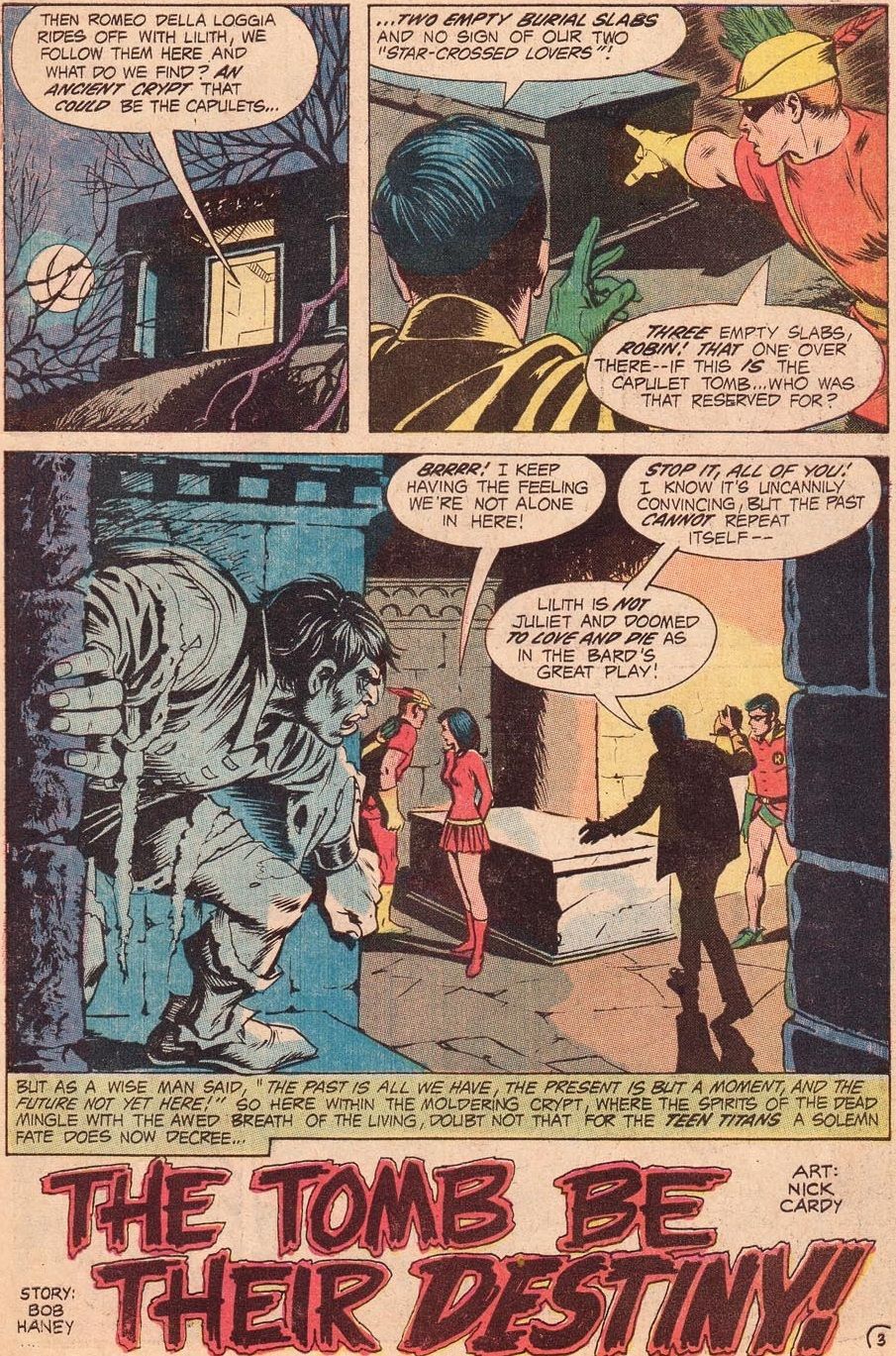

They're just investigating some haunted stuff in Teen Titans #36...

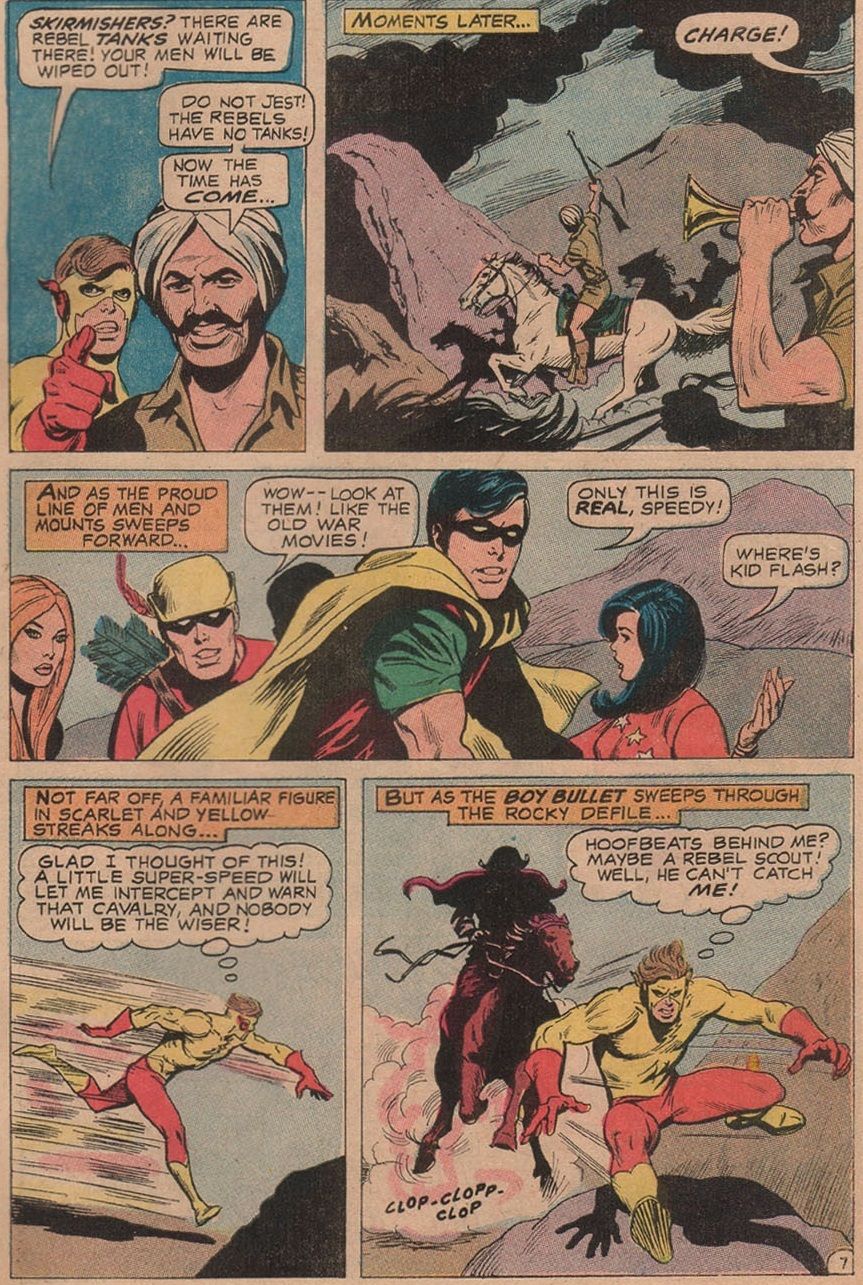

Helping with a foreign war in #37...

Teen Titans #38 was a reprint, but I just love the reprint they chose, which makes it look like Speedy is jonesing for some heroin...

Teen Titans #39 sees the Titans involved in some nonsense with their prehistoric friend, Gnarrk...

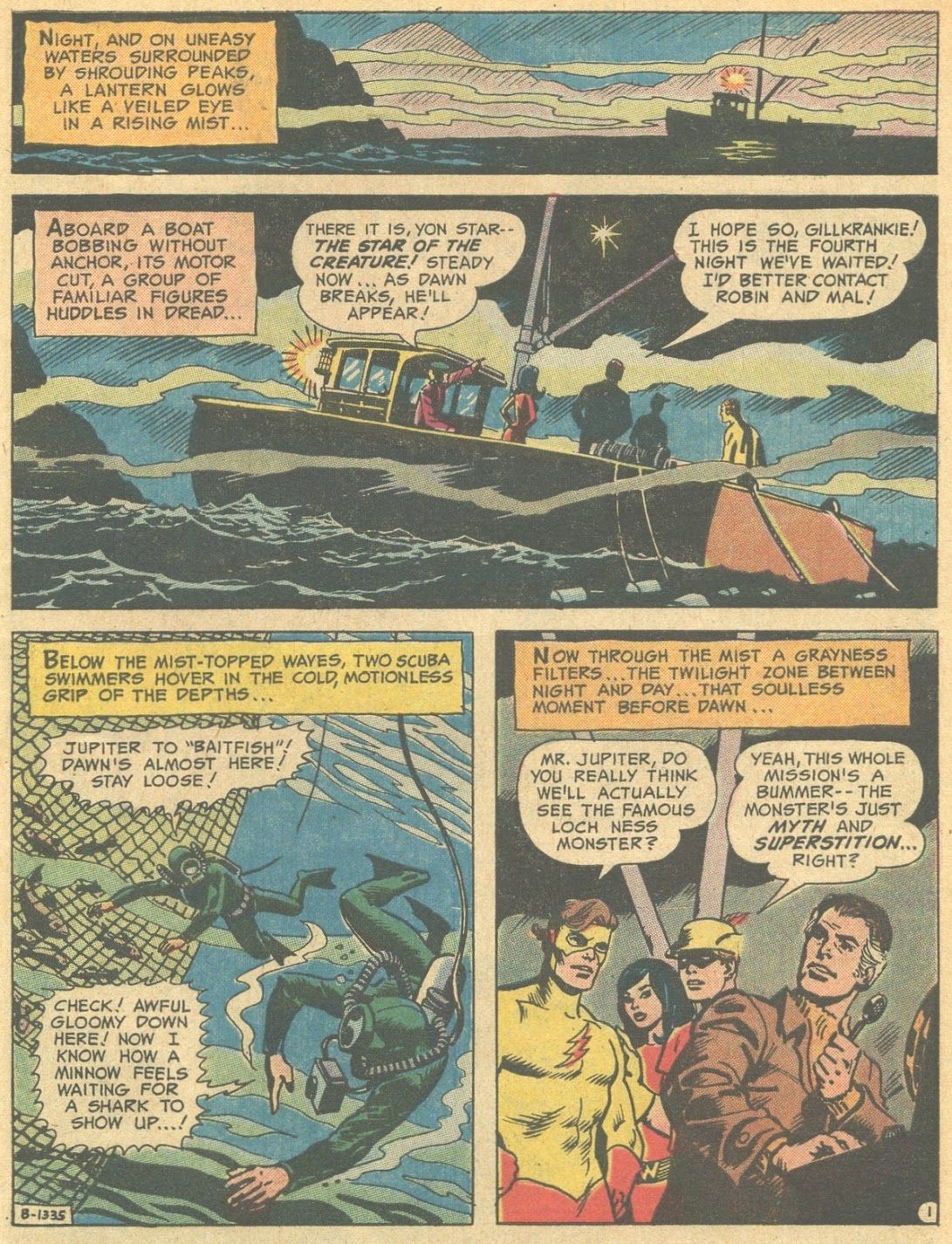

They're looking for the Loch Ness Monster in Teen Titans #40...

They're fighting a slave-owner ghost in Teen Titans #41...

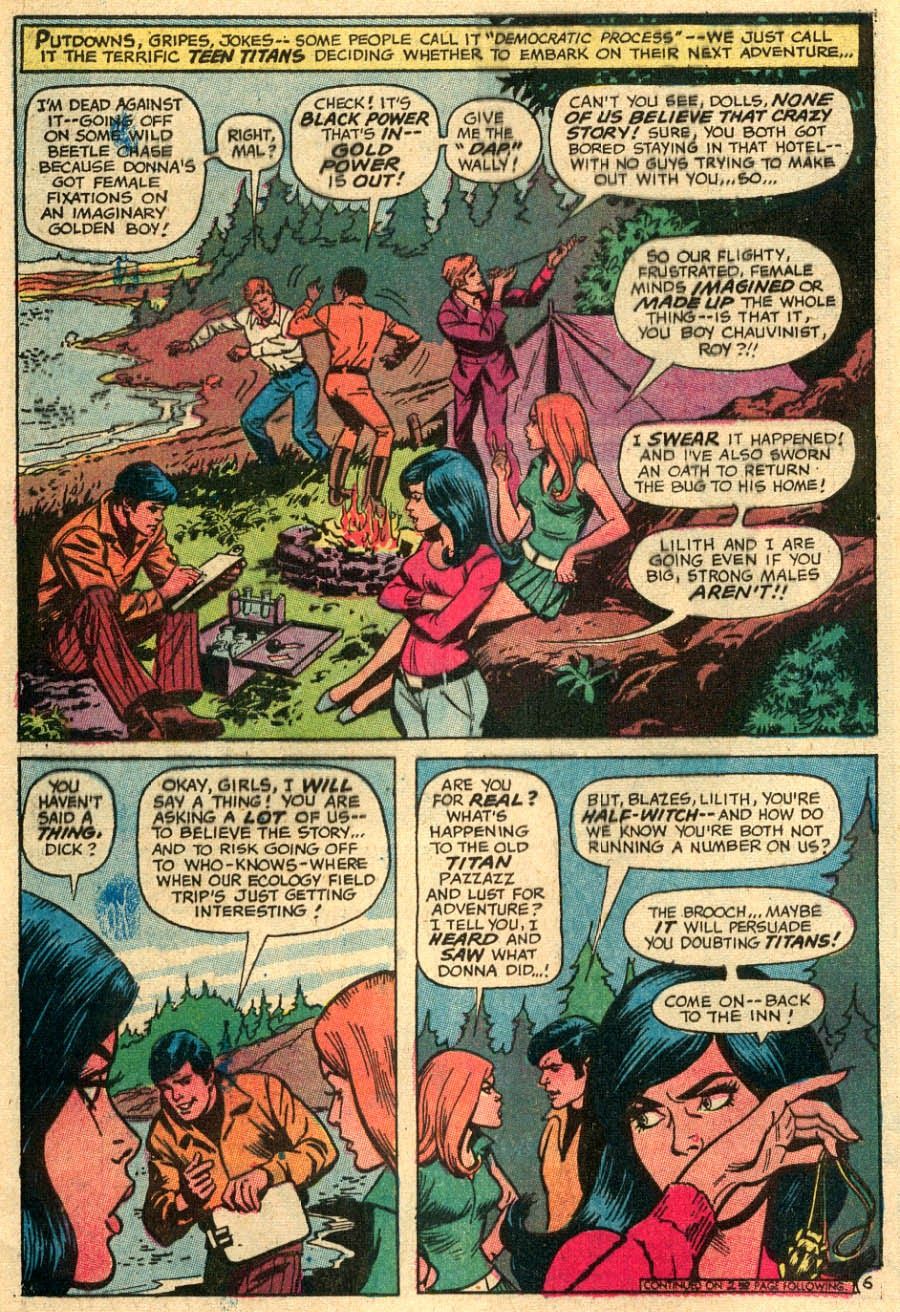

They're camping in Teen Titans #42...

And they're fighting some goblins in the final issue of the series before it was canceled...

The series picked up four years later, in 1976, and hilariously, Speedy's entire drug problem was set BETWEEN Teen Titans #43 and #44! So despite many issues coming out after Green Lantern #85-6, all of them were set before #85, and so the whole problem resolved itself before #44.

That's a pretty hilarious choice of avoiding the subject in a big way.

Then again, so is Speedy kicking his heroin habit in a couple of days.

Okay, folks, if you have a suggestion for another clever piece of shared continuity, drop me a line at brianc@cbr.com!

"Snowbirds Don't Fly" is a two-part anti-drug comic book story arc which appeared in Green Lantern/Green Arrow issues 85 and 86, published by DC Comics in 1971. The story was written by Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams, with the latter also providing the art with Dick Giordano. It tells the story of Green Lantern and Green Arrow, who fight drug dealers, witnessing that Green Arrow's ward Roy "Speedy" Harper is a drug addict and dealing with the fallout of his revelation. Considered a watershed moment in the depiction of mature themes in DC Comics,[1] the tone of this story is set in the tagline on the cover: "DC attacks youth's greatest problem... drugs!"

Plot[edit]

In the first part (Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85), Green Arrow (Oliver Queen) runs into muggers who shoot him with a crossbow. Strangely, the weapon is loaded with his own arrows. Tracking down the attackers, Green Arrow and his best friend, Green Lantern Hal Jordan, find out that the muggers are addicts who need money, and are surprised to find Queen's ward Speedy (Roy Harper) among them. They think he is working undercover to bust them, but Queen catches him red-handed when he tries to shoot heroin. It becomes evident that the stolen arrows are indeed Queen's, which he shares with Harper when they fight crime together. In the second part (Green Lantern/Green Arrow #86), an enraged Green Arrow lashes out at his ward. In shame, Harper withdraws cold turkey, and one of the other addicts dies of a drug overdose. Queen and Lantern tackle the kingpin of the drug ring, a pharmaceutics CEO who outwardly condemns drug abuse, and attend the funeral of the addict who passed.

Background[edit]

During the 1960s, Green Lantern was on the verge of cancellation, which gave writer Denny O'Neil a great deal of creative freedom when he was assigned the series. O'Neil recounted that "my journalism background and laid-back social activism had led me to wonder if I couldn't combine those things with what I did for a living. ... So this was my chance to see if this idea I had would work. It was a situation where nobody had anything to lose. And I think that writing about things that really concerned me pulled out of me a higher level of craft. Also, it gave me real problems to solve in terms of craft which I hadn't faced before."[2] The first of these "socially motivated" Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories was written with Gil Kane slated to be the artist, but Kane dropped out and was replaced by Neal Adams.[2]

The O'Neil/Adams run met with a high level of media attention and critical acclaim including five Shazam Awards at the May 1971 ceremony, but by the time of "Snowbirds Don't Fly", Adams felt that they had run out of steam and were producing stories which lacked true relevance.[3] He responded by pushing for a story dealing with drug addiction, an issue both he and O'Neill had been wanting to tackle, and had encountered firsthand: Adams was chairman of his neighborhood drug rehabilitation center, and O'Neil lived in a neighborhood with a large number of addicts. O'Neil recounted, "I saw people nodding out from heroin every day on the street. I had friends with drug problems, people coming over at 3 a.m. with the shakes."[3] When Adams first drew the cover showing Speedy with heroin paraphernalia, editor Julius Schwartz rejected it, since it would not have been approved by the Comics Code Authority.[4] (The Comics Code prohibited the depiction of drug abuse, even in a totally condemning context.) O'Neil said that Schwartz "was very supportive" during his run on Green Lantern, and that he found the Comics Code to be his biggest restriction when confronting social issues.[2]

Then, Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 (May–July 1971) was published by rival comic publishing house Marvel Comics, which showed major supporting character Harry Osborn struggling with drug addiction. It was the first comic from a major publisher to be published without the Comics Code Authority's seal of approval since 1954, when the Comics Code Authority was founded. Adams said: "We could have done it first and been the ones to make a big move. Popping a pill and walking off a roof isn't the sort of thing that really happens [referring to a scene in Amazing Spider-Man #96], but heroin addiction is; to have it happen to one of our heroes was potentially devastating. Anyway, the publishers at DC, Marvel and the rest called a meeting, and in three weeks, the Comics Code was completely rewritten. And we did our story."[4]

Questioned why Roy Harper (Speedy) was chosen to illustrate drug abuse, O'Neil said that "We chose Roy [Harper] for maximum emotional impact. We thought an established good guy in the throes of addiction would be stronger than we... some character we'd have made up for the occasion. Also, we wanted to show that addiction was not limited to 'bad' or 'misguided' kids."[4]

O'Neil's original ending to the story had Speedy overcoming his drug habit on his own and reconciling with Green Arrow. Adams protested that this ending was too anticlimactic. When O'Neil said he disagreed, Adams scripted two new pages on his own and showed them to Schwartz. Schwartz approved of Adams's revision and had it published instead of O'Neil's ending.[3] In a 1975 article for The Amazing World of DC Comics, O'Neil stated that he still felt Adams's conclusion was not as good as the original ending: "I disapprove of the implied conclusion of that story. What’s implied is that a punch in the mouth solves everything."[3]

Awards and recognition[edit]

The "Snowbirds Don't Fly" arc won the 1971 Shazam Award for "Best Individual Story".[5] New York Mayor John Lindsay wrote a letter to DC in response to the matter, commending them, which was printed in issue #86. In 2004, Comic Book Resources author Jonah Weiland called the "Snowbirds Don't Fly" arc the start of an era of socially relevant Green Lantern/Green Arrow comics, a slant which eventually opened up the DC world to other minorities (such as homosexual characters) and climaxed in the character of Mia Dearden (Roy Harper's successor as Green Arrow's/Oliver Queen's sidekick "Speedy"), who is not only a victim of child prostitution but also later portrayed as HIV positive. Despite her sad fate, she is explicitly portrayed as a positive, pro-active hero by writer Judd Winick.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ McAvennie, Michael (2010). "1970s". In Dolan, Hannah (ed.). DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. Dorling Kindersley. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

It was taboo to depict drugs in comics, even in ways that openly condemned their use. However, writer Denny O'Neil and artist Neal Adams collaborated on an unforgettable two-part arc that brought the issue directly into Green Arrow's home, and demonstrated the power comics had to affect change and perception.

- ^ a b c Zimmerman, Dwight Jon (August 1986). "Denny O'Neil". Comics Interview. No. 35. Fictioneer Books. pp. 22–37.

- ^ a b c d Wells, John (December 2010). "Green Lantern/Green Arrow: And Through Them Change an Industry". Back Issue! (45). TwoMorrows Publishing: 39–54.

- ^ a b c "Roy Harper: Teen Sidekick, Drug User". Titans Tower. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "1971 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards". hahnlibrary.net. 1972. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30.

- ^ Weiland, Jonah (October 14, 2004). "Winick on 'Green Arrow,' Mia's HIV Status and More". ComicBookResources.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

Green Goblin Reborn!" is a 1971 Marvel Comics story arc which features Spider-Man fighting against his arch enemy Norman Osborn, the Green Goblin. This arc was published in The Amazing Spider-Man #96–98 (May–July 1971) and was plotted and written by Stan Lee, with art by penciler Gil Kane and inker John Romita Sr. It is recognized as the first mainstream comic publication which portrayed and condemned drug abuse since the formation of the Comics Code Authority, and in time led to the revision of the Code's rigidity.

Plot outline[edit]

Issue #96 begins with Peter Parker, who is low on funds, moving in with Harry Osborn and accepting a job with Harry's father, Norman. Parker knows Norman Osborn is secretly Spider-Man's arch enemy, the Green Goblin; however, Osborn currently has amnesia and doesn't remember Parker's double identity as Spider-Man. Soon, Spider-Man sees a man dancing on a rooftop and claiming he can fly. When the man falls, Spider-Man saves him. Realizing the man is high on drugs, he says "I would rather face a hundred super-villains than throw my life away on hard drugs, because it is a battle you cannot win!" At the end of issue #96, Norman Osborn regains his memory and turns into the Green Goblin again.

In issue #97, the Green Goblin attacks Spider-Man, then disappears mysteriously. At home, Parker is shocked to find that Harry is popping pills because Harry's love interest Mary Jane Watson was affectionate toward Parker. Later, while Spider-Man is hunting the Green Goblin, Harry buys more drugs and suffers a drug overdose. Parker finds him in time to rush him to the hospital. In issue #98, Spider-Man lures the Green Goblin to Harry's hospital room. When he sees his sick son, Norman Osborn faints, and the Green Goblin is vanquished. At the end of issue #98, Peter and his estranged girlfriend Gwen Stacy rekindle their relationship.

Historical significance[edit]

This was the first story arc in mainstream comics that portrayed and condemned the abuse of drugs. This effectively led to the revision of the Comics Code. Previously, the Code forbade the depiction of the use of illegal drugs, even negatively. However, in 1970 the Nixon administration's Department of Health, Education, and Welfare asked Stan Lee to publish an anti-drug message in one of Marvel's top-selling titles.[1] Lee chose the top-selling The Amazing Spider-Man; issues #96–98 (May–July 1971) feature a story arc depicting the negative effects of drug use. Acknowledging that young readers (the primary audience for Amazing Spider-Man) do not like being lectured to, Lee wrote the story to focus on the entertainment value, with the anti-drug message inserted as subtly as possible.[2]

While the story had a clear anti-drug message, the Comics Code Authority refused to issue its seal of approval. Marvel nevertheless published the three issues without the Comics Code Authority's approval or seal. The issues sold so well that the industry's self-censorship was undercut[1] and the Code was subsequently revised.[3] Weeks later, DC Comics published a two-issue story in the series Green Lantern in which Green Arrow's teen-aged ward, Speedy, starts using heroin when his mentor leaves him to travel across America with Green Lantern.

Lee recalled in a 1998 interview:

Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Joe Quesada called it the one Spider-Man comic that made him a lifelong fan, saying his father "encouraged [me] to read these issues and... I really got hooked... What my father didn't realize was that he was starting a whole other addiction [to comic books]".[5]

See also[edit]

- "Snowbirds Don't Fly" — the first DC Comics anti-drug arc, featuring Green Arrow sidekick Speedy as a junkie. It also was published in 1971, weeks after the "Green Goblin Reborn" arc.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Wright, p. 239

- ^ Manner, Jim (October 2010). "Cracking the Code: The Spider-Man Drug Issues". Back Issue! (#44). TwoMorrows Publishing: 3–6.

- ^ Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics, Marvel by Les Daniels, Page 152

- ^ "Stan the Man & Roy the Boy: A Conversation Between Stan Lee and Roy Thomas", Comic Book Artist #2 (Summer 1998). WebCitation archive.

- ^ Sanderson, Peter."Comics in Context" #168 Archived 2008-10-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2007

Fully examined here:

I will present this content in a future post.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2404.21 - 10:10

- Days ago = 3215 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment