A Sense of Doubt blog post #1891 - "Laziness Does Not Exist"and commentary for composition students

Greetings and welcome to my blog.

If you're a student in one of my classes, you know why you're here. We're reading this article and summarizing it as step one in writing an essay about it and its content.

If you're not a student, I am glad you have found this post by chance as the Devon Price article is excellent. Find the link to the original publication in Medium via the title below at the start of the original.

My goal with this post is to provide some commentary about the article for anyone who has read it, but most importantly for my students as they begin their summaries and eventual essays. My commentary appears after the sharing of the original article.

But unseen barriers do

I've been a psychology professor since 2012. In the past six years, I’ve witnessed students of all ages procrastinate on papers, skip presentation days, miss assignments, and let due dates fly by. I’ve seen promising prospective grad students fail to get applications in on time; I’ve watched PhD candidates take months or years revising a single dissertation draft; I once had a student who enrolled in the same class of mine two semesters in a row, and never turned in anything either time.

I don’t think laziness was ever at fault.

Ever.

In fact, I don’t believe that laziness exists.

***

I’m a social psychologist, so I’m interested primarily in the situational and contextual factors that drive human behavior. When you’re seeking to predict or explain a person’s actions, looking at the social norms, and the person’s context, is usually a pretty safe bet. Situational constraints typically predict behavior far better than personality, intelligence, or other individual-level traits.

So when I see a student failing to complete assignments, missing deadlines, or not delivering results in other aspects of their life, I’m moved to ask: what are the situational factors holding this student back? What needs are currently not being met? And, when it comes to behavioral “laziness,” I’m especially moved to ask: what are the barriers to action that I can’t see?

There are always barriers. Recognizing those barriers— and viewing them as legitimate — is often the first step to breaking “lazy” behavior patterns.

***

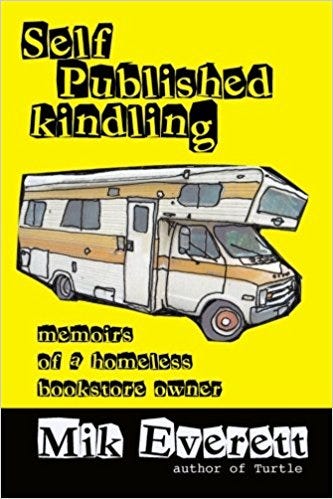

It’s really helpful to respond to a person’s ineffective behavior with curiosity rather than judgment. I learned this from a friend of mine, the writer and activist Kimberly Longhofer (who publishes under the name Mik Everett). Kim is passionate about the acceptance and accommodation of disabled people and homeless people. Their writing about both subjects is some of the most illuminating, bias-busting work I’ve ever encountered. Part of that is because Kim is brilliant, but it’s also because at various points in their life, Kim has been both disabled and homeless.

Kim is the person who taught me that judging a homeless person for wanting to buy alcohol or cigarettes is utter folly. When you’re homeless, the nights are cold, the world is unfriendly, and everything is painfully uncomfortable. Whether you’re sleeping under a bridge, in a tent, or at a shelter, it’s hard to rest easy. You are likely to have injuries or chronic conditions that bother you persistently, and little access to medical care to deal with it. You probably don’t have much healthy food.

In that chronically uncomfortable, over-stimulating context, needing a drink or some cigarettes makes fucking sense. As Kim explained to me, if you’re laying out in the freezing cold, drinking some alcohol may be the only way to warm up and get to sleep. If you’re under-nourished, a few smokes may be the only thing that kills the hunger pangs. And if you’re dealing with all this while also fighting an addiction, then yes, sometimes you just need to score whatever will make the withdrawal symptoms go away, so you can survive.

|

| Kim’s incredible book about their experiences being homeless while running a bookstore. |

Few people who haven’t been homeless think this way. They want to moralize the decisions of poor people, perhaps to comfort themselves about the injustices of the world. For many, it’s easier to think homeless people are, in part, responsible for their suffering than it is to acknowledge the situational factors.

And when you don’t fully understand a person’s context — what it feels like to be them every day, all the small annoyances and major traumas that define their life — it’s easy to impose abstract, rigid expectations on a person’s behavior. All homeless people should put down the bottle and get to work. Never mind that most of them have mental health symptoms and physical ailments, and are fighting constantly to be recognized as human. Never mind that they are unable to get a good night’s rest or a nourishing meal for weeks or months on end. Never mind that even in my comfortable, easy life, I can’t go a few days without craving a drink or making an irresponsible purchase. They have to do better.

But they’re already doing the best they can. I’ve known homeless people who worked full-time jobs, and who devoted themselves to the care of other people in their communities. A lot of homeless people have to navigate bureaucracies constantly, interfacing with social workers, case workers, police officers, shelter staff, Medicaid staff, and a slew of charities both well-meaning and condescending. It’s a lot of fucking work to be homeless. And when a homeless or poor person runs out of steam and makes a “bad decision,” there’s a damn good reason for it.

If a person’s behavior doesn’t make sense to you, it is because you are missing a part of their context. It’s that simple. I’m so grateful to Kim and their writing for making me aware of this fact. No psychology class, at any level, taught me that. But now that it is a lens that I have, I find myself applying it to all kinds of behaviors that are mistaken for signs of moral failure — and I’ve yet to find one that can’t be explained and empathized with.

***

Let’s look at a sign of academic “laziness” that I believe is anything but: procrastination.

People love to blame procrastinators for their behavior. Putting off work sure looks lazy, to an untrained eye. Even the people who are actively doing the procrastinating can mistake their behavior for laziness. You’re supposed to be doing something, and you’re not doing it — that’s a moral failure right? That means you’re weak-willed, unmotivated, and lazy, doesn’t it?

For decades, psychological research has been able to explain procrastination as a functioning problem, not a consequence of laziness. When a person fails to begin a project that they care about, it’s typically due to either a) anxiety about their attempts not being “good enough” or b) confusion about what the first steps of the task are. Not laziness. In fact, procrastination is more likely when the task is meaningful and the individual cares about doing it well.

When you’re paralyzed with fear of failure, or you don’t even know how to begin a massive, complicated undertaking, it’s damn hard to get shit done. It has nothing to do with desire, motivation, or moral upstandingness. Procastinators can will themselves to work for hours; they can sit in front of a blank word document, doing nothing else, and torture themselves; they can pile on the guilt again and again — none of it makes initiating the task any easier. In fact, their desire to get the damn thing done may worsen their stress and make starting the task harder.

The solution, instead, is to look for what is holding the procrastinator back. If anxiety is the major barrier, the procrastinator actually needs to walk away from the computer/book/word document and engage in a relaxing activity. Being branded “lazy” by other people is likely to lead to the exact opposite behavior.

Often, though, the barrier is that procrastinators have executive functioning challenges — they struggle to divide a large responsibility into a series of discrete, specific, and ordered tasks. Here’s an example of executive functioning in action: I completed my dissertation (from proposal to data collection to final defense) in a little over a year. I was able to write my dissertation pretty easily and quickly because I knew that I had to a) compile research on the topic, b) outline the paper, c) schedule regular writing periods, and d) chip away at the paper, section by section, day by day, according to a schedule I had pre-determined.

Nobody had to teach me to slice up tasks like that. And nobody had to force me to adhere to my schedule. Accomplishing tasks like this is consistent with how my analytical, Autistic, hyper-focused brain works. Most people don’t have that ease. They need an external structure to keep them writing — regular writing group meetings with friends, for example — and deadlines set by someone else. When faced with a major, massive project, most people want advice for how to divide it into smaller tasks, and a timeline for completion. In order to track progress, most people require organizational tools, such as a to-do list, calendar, datebook, or syllabus.

Needing or benefiting from such things doesn’t make a person lazy. It just means they have needs. The more we embrace that, the more we can help people thrive.

***

I had a student who was skipping class. Sometimes I’d see her lingering near the building, right before class was about to start, looking tired. Class would start, and she wouldn’t show up. When she was present in class, she was a bit withdrawn; she sat in the back of the room, eyes down, energy low. She contributed during small group work, but never talked during larger class discussions.

A lot of my colleagues would look at this student and think she was lazy, disorganized, or apathetic. I know this because I’ve heard how they talk about under-performing students. There’s often rage and resentment in their words and tone — why won’t this student take my class seriously? Why won’t they make me feel important, interesting, smart?

But my class had a unit on mental health stigma. It’s a passion of mine, because I’m a neuroatypical psychologist. I know how unfair my field is to people like me. The class & I talked about the unfair judgments people levy against those with mental illness; how depression is interpreted as laziness, how mood swings are framed as manipulative, how people with “severe” mental illnesses are assumed incompetent or dangerous.

The quiet, occasionally-class-skipping student watched this discussion with keen interest. After class, as people filtered out of the room, she hung back and asked to talk to me. And then she disclosed that she had a mental illness and was actively working to treat it. She was busy with therapy and switching medications, and all the side effects that entails. Sometimes, she was not able to leave the house or sit still in a classroom for hours. She didn’t dare tell her other professors that this was why she was missing classes and late, sometimes, on assignments; they’d think she was using her illness as an excuse. But she trusted me to understand.

And I did. And I was so, so angry that this student was made to feel responsible for her symptoms. She was balancing a full course load, a part-time job, and ongoing, serious mental health treatment. And she was capable of intuiting her needs and communicating them with others. She was a fucking badass, not a lazy fuck. I told her so.

She took many more classes with me after that, and I saw her slowly come out of her shell. By her Junior and Senior years, she was an active, frank contributor to class — she even decided to talk openly with her peers about her mental illness. During class discussions, she challenged me and asked excellent, probing questions. She shared tons of media and current-events examples of psychological phenomena with us. When she was having a bad day, she told me, and I let her miss class. Other professors — including ones in the psychology department — remained judgmental towards her, but in an environment where her barriers were recognized and legitimized, she thrived.

***

|

| Photo by Janos Richter, courtesy of Unsplash |

Over the years, at that same school, I encountered countless other students who were under-estimated because the barriers in their lives were not seen as legitimate. There was the young man with OCD who always came to class late, because his compulsions sometimes left him stuck in place for a few moments. There was the survivor of an abusive relationship, who was processing her trauma in therapy appointments right before my class each week. There was the young woman who had been assaulted by a peer — and who had to continue attending classes with that peer, while the school was investigating the case.

These students all came to me willingly, and shared what was bothering them. Because I discussed mental illness, trauma, and stigma in my class, they knew I would be understanding. And with some accommodations, they blossomed academically. They gained confidence, made attempts at assignments that intimidated them, raised their grades, started considering graduate school and internships. I always found myself admiring them. When I was a college student, I was nowhere near as self-aware. I hadn’t even begun my lifelong project of learning to ask for help.

***

Students with barriers were not always treated with such kindness by my fellow psychology professors. One colleague, in particular, was infamous for providing no make-up exams and allowing no late arrivals. No matter a student’s situation, she was unflinchingly rigid in her requirements. No barrier was insurmountable, in her mind; no limitation was acceptable. People floundered in her class. They felt shame about their sexual assault histories, their anxiety symptoms, their depressive episodes. When a student who did poorly in her classes performed well in mine, she was suspicious.

It’s morally repugnant to me that any educator would be so hostile to the people they are supposed to serve. It’s especially infuriating, that the person enacting this terror was a psychologist. The injustice and ignorance of it leaves me teary every time I discuss it. It’s a common attitude in many educational circles, but no student deserves to encounter it.

***

I know, of course, that educators are not taught to reflect on what their students’ unseen barriers are. Some universities pride themselves on refusing to accommodate disabled or mentally ill students — they mistake cruelty for intellectual rigor. And, since most professors are people who succeeded academically with ease, they have trouble taking the perspective of someone with executive functioning struggles, sensory overloads, depression, self-harm histories, addictions, or eating disorders. I can see the external factors that lead to these problems. Just as I know that “lazy” behavior is not an active choice, I know that judgmental, elitist attitudes are typically borne out of situational ignorance.

And that’s why I’m writing this piece. I’m hoping to awaken my fellow educators — of all levels — to the fact that if a student is struggling, they probably aren’t choosing to. They probably want to do well. They probably are trying. More broadly, I want all people to take a curious and empathic approach to individuals whom they initially want to judge as “lazy” or irresponsible.

If a person can’t get out of bed, something is making them exhausted. If a student isn’t writing papers, there’s some aspect of the assignment that they can’t do without help. If an employee misses deadlines constantly, something is making organization and deadline-meeting difficult. Even if a person is actively choosing to self-sabotage, there’s a reason for it — some fear they’re working through, some need not being met, a lack of self-esteem being expressed.

People do not choose to fail or disappoint. No one wants to feel incapable, apathetic, or ineffective. If you look at a person’s action (or inaction) and see only laziness, you are missing key details. There is always an explanation. There are always barriers. Just because you can’t see them, or don’t view them as legitimate, doesn’t mean they’re not there. Look harder.

Maybe you weren’t always able to look at human behavior this way. That’s okay. Now you are. Give it a try.

|

| Get over that wall! Photo by Samuel Zeller, courtesy of Unsplash. |

If you found this essay illuminating at all, please consider buying Kim Longhofer / Mik Everett’s book, Self-Published Kindling: Memoirs of a Homeless Bookstore Owner. The ebook is $3; the paperback is $15.

If you found this essay illuminating at all, please consider buying Kim Longhofer / Mik Everett’s book, Self-Published Kindling: Memoirs of a Homeless Bookstore Owner. The ebook is $3; the paperback is $15.

Kim also runs a fat-positive, cripplepunk page called Change Like the Moon: Accept Every Body at Every Phase.

A Medium publication about humanity: yours, mine, and ours

MY COMMENTARY

Students take note. What I have here are my first attempt at thoughts about this article. The following is not an example of either a summary or an essay about Price's article. I am simply sharing thoughts as they occur to me. If I were to transform this content into essay form, I would rethink and restructure as well as remove the second person address from my personal experience. Though I would keep the majority of the text in third person, I need first person for the personal experience content. I might also be more strict with cites as I revise and reorganize. I have a couple of cites to Price's original (using page numbers from the PDF), but I surely could add more for material I paraphrased.

NOTE: Paragraph numbers are not required in MLA form, but I like them as they provide needed data for access and verification. MLA suggests using "par" before the number, but I prefer the APA form of "para" as the abbreviation as it seems clearer. Though I am using MLA form, sort of, I am deviating from it with the disclaimer here showing that I know what I am doing. Model my behaviour? (I also like British spellings.) :-)

IMPORTANT: The appropriate pronoun for Devon Price is they. Ditto for Kimberly Longhofer.

Price presents an argument about laziness as a misinterpretation of a student's context and barriers to learning. They argue that laziness does not exist but rather that students have all kinds of barriers to starting work; continuing to work, especially on large projects; and ultimately, completing work.

In my own personal experience as a student or a worker, I can agree with Price's main supposition. I refer to it as the mountain. For example, one mountain in my life is our backyard fence. When we moved into this house in 2017, the builders told us to paint or stain our side of the backyard fence, the side facing the back of the house, the following summer to preserve the wood. That would have been the summer of 2018. We're about to enter the summer of 2020 and have not yet painted that fence.

I know that painting the fence will be relatively easy to do. The job will take most of a day and will go quicker if I have help. Last summer went by, and I did not get to the job. I had time off work. I could have done it. So why didn't I do it? THE MOUNTAIN. Getting started feels like a mountain that needs to be moved. Have you ever tried to move a mountain? Go, give it a try; we have several within a short drive of my house in south-western Washington. Didn't budge, right?

I know that once I start the job, I will finish easily. Price's article helped me think about the barriers to getting started. Getting the stain requires money and a trip to the paint store, the hardware store, Home Depot, or somewhere comparable. I will need brushes and pans and roller and all that gear that I used to own in Michigan and gave away because we did not have room in the moving truck. When I am trying to save money -- I am ALWAYS TRYING to save money -- spending it feels like a failure or like a thing that needs to be scheduled for when I feel flush enough for the expense. So, money erects the first barrier in my way.

Psychology stamps down another wall between start and completion. More or less jobless last summer, I was depressed. It felt impossible to muster the wherewithal to be productive with household chores, especially since I needed to put all my extra time into applying for jobs. So add anxiety to the depression. I felt much more anxiety about being nearly without money due to being jobless. And I am back to money again as a big barrier.

Also, I missed my Dad. Though my Dad helped me drive a trailer and the dogs across the country in 2017, he returned to Michigan. I usually did jobs like this with my Dad. Father-son bonding time. I don't have that now.

Also, I don't like these kinds of jobs. I would rather write either here in my blog or on a fiction story in a word processing file, ones I do not keep online.

I could probably think of more barriers, but you get the drift of my ideas. I can relate to what Price argues about barriers to starting and completing work of any kind. And some of the barriers are much more serious than my pity party of financial woes, depression, and homesickness. Some students have serious mental illness which they are attempting to navigate, others have child care issues, some are working third shift hours and lack sleep, some are struggling with self esteem issues, and many face a combination of these and other barriers to doing their schoolwork and being successful.

Price starts the article with an example for better context citing the writing of Kimberly Longhofer, who writes as Mik Everett, with their advocacy for the acceptance and accommodation of disabled and homeless people (Price, 2). Longhofer taught the folly of judging homeless people for spending the money earned from begging on alcohol and cigarettes. In the life of a homeless person, the warmth provided by alcohol or the pain soothing effect of nicotine may be the only things that help that person survive another cold, brutal night on the streets. Condemning the homeless for their addictions is a common judgmental criticism against them and their behavior. But seen in context, understanding the safety issues, the lingering health issues, the poor diet, the impact of weather, theft, assault, sexual assault, and even untreated mental illness, perhaps those quick to make their donations to the homeless contingent on them "cleaning up their act" might think again. Context is everything, Price argues. If anyone walked a night in a homeless person's shoes, or lack of good shoes, those judgments would quickly evaporate.

Price connects the need for context with the homeless with students because teachers and administrators are quick to judge students as "lazy" when they skip class or fail to complete assignments on time or at all. Remember: context is everything. Price trots out a series of examples about students who other teachers had dismissed as lazy losers who then thrived in Price's classes because they (Price) made the effort to understand the context, the barriers the students faced.

Price identifies the most common causes of what are usually labeled as "procrastination" as anxiety about failure and/or lack of understanding of how to complete the task (Price, 3). Price describes those who struggle with completion as ones who need to improve "executive functioning" (Price, 4). They compare their own work in completing a dissertation in a year (which is fast) as the ability to break the large project into more achievable micro-tasks, IE. having a plan and a schedule for completion. For most students, these are the necessary skills. Break down the big task into as many smaller tasks as one can plan, schedule the time to do the work, and cross off completed stages as one goes. Every time a person crosses an item off a to-do list the sense of accomplish produces a surge of dopamine in the brain, the great neurotransmitter of pleasure (Sáez, para 2). Once someone starts to feel the benefits of a brain frequently awash with dopamine from working through a to-do list, it's easy to break down big projects to smaller ones to have more things to cross off the list.

Though Price explores more serious barriers faced by students, such as mental illness, it's the seemingly lazy students who are the most common; however, Price argues that all students have a context and that if educators can work to understand the context, then educators of all shapes and sizes can help those students be successful. If so, is there really no such thing as procrastination and laziness? Is all inactivity due to barriers produced by that person's context? I am not wholly convinced, and so here's some counter arguments, which I know is a clumsy way to introduce them, but as I stated, this is not a final draft.

Some students are lazy. I have had students admit to me that the reason for not starting is procrastination, is laziness. Other students have claimed that they don't know why they haven't started a big project and that they have a problem with procrastination. However, are these claims correct? Or do they fit Price's definition of unseen barriers? The students who claim to be lazy and procrastinators must have some barriers to the work whether those be understanding the whole project, knowing the first step to take, fear of failure, or struggles to limit or eliminate distractions. When pressed, most of these students have a good work ethic when it comes to other things. They produce things; they accomplish things. It's all about the priorities. School work does not rank above making dinner for their family, volunteer work at the church, babysitting for their cousins, or mowing the lawn. They are active; they are just not actively doing school work. But are they thinking about it? What are they thinking? Can we as educators get at the barriers so as to help the student be successful, assuming being successful is what the student wants?

Those who do not know why they are "procrastinating" clearly have barriers. Almost all of these students have self-esteem issues. I can see it when they talk to me. They may be playing video games all night or streaming animé until five a.m. but they are avoiding the risky enterprise of doing homework and receiving the confirmation of what their self esteem whispers below the surface of consciousness: that they are losers and will end up like the homeless people that they viciously condemn as what Scrooge called "the surplus population" in "A Christmas Carol" (Dickens, 5, location 771). Scrooge insinuated that these "waste of humanity," the poor who need "alms" at Christmas time. Likewise, these students need the "merciful deeds" (definition of alms - see Matthew in the Bible) from their educators. Their inactivity reflects my own. I need help to paint that fence, which is still not painted. The more educators talk to these students to try to find out what's going on with them, the greater the likelihood of uncovering the barriers to success.

Here I am using the grand we because I am an educator and I using plural of first person. We educators want to help, or we are supposed to want to help. It's our job to help. It's the moral imperative we signed on for when took the "Pedagogic Oath" of service and fealty to learning and intellectualism. Price asserted as much in their article in expressing why "it’s morally repugnant to me that any educator would be so hostile to the people they are supposed to serve. It’s especially infuriating, that the person enacting this terror was a psychologist. The injustice and ignorance of it leaves me teary every time I discuss it. It’s a common attitude in many educational circles, but no student deserves to encounter it" (Price, 6, para 28). And yet, do we educators always have the time to discover a student's context, a student's barriers to success? How many classes are we teaching? How many student are in those classes? How much time can we devote to each? And furthermore, does every student want the individual attention of a professor, however well liked, invading his/her/their privacy to uncover those hidden, unvoiced barriers?

It's all like parenting. People parent as they were parented, improving only somewhat on the model if they are self-aware, emotionally-rich, present, and thoughtful. Others just repeat history. Same with educators. We teach as we were taught, just a little less cruelly, giving students the help we wish we had received some of the time. But ultimately, we have to put the hammer down, we have to lower the boom, we have to talk the talk of the tough love, the mean streets, the reality principle. Extensions, understanding, empathy are all well and good, but ultimately, there's a hard deadline called the end of the quarter, and if we educators give all students maximum time to complete a large task, it means giving ourselves much less time to assess it, which leads to haste, frustration, bitterness, and bad choices, the very PROBLEM Price describes of the "unflinchingly rigid" (Price, 6, para 27) instructors from whom unsuccessful students had to flee. Being too accommodating means being taken advantage of. I learned many great lessons from the uncompromising task-masters. I learned to meet deadlines when my feet were held to the fire. There's some value in those who are unflinchingly rigid, and yet, Price argues that we educators do not have to be door mats, we just need to try to meet students where they are and offer a helping hand equally to all. If we're not willing to do that much, then why are we in this career at all.

Now, who wants to help me stain my fence?

NOTE: In counting paragraphs, I lumped one liners together with other parts as one, but with page and paragraph numbers, one should easily find paraphrases or quotes in the original.

NOTE: I cannot make hanging indents on the blog.

WORKS CITED

NOTE: Location number in in text cite refers to Kindle location. Page is the print edition page.

Price, Devon. “Laziness Does Not Exist.” Medium: Human Parts, Medium Corporation, 23 Mar. 2018, humanparts.medium.com/laziness-does-not-exist-3af27e312d01.

Sáez, Francisco. “Micro-Tasks. The Pleasure of Checking Off.” Facile Things: The Ultimate Solution to Get Things Done, David Allen Company, 2019, facilethings.com/blog/en/micro-tasks.

WRAPPING UP

As my disclaimer professes, I wrote "commentary" as a free write, pre-writing collection of thoughts and content produced from close reading. The content I created is not a good essay on Price's article. But if I am a student writing on this article, I have a lot to work with.

There's clay to be molded here. Now I have to shape, mold, trim, and bake in the kiln before I slather on the glaze.

I have some personal experience that provides an entry point into the article, though it's kind of long. I have a partial summary of Price's article but it's all spread out throughout my content. I did not write a start-to-finish summary before I started to make arguments and analyze content.

I also did not compose a thesis, but I have all the building blocks to create one and to re-structure my content to advance and argue it. I have discovered that I agree with Price. Even when I attempted to make counter arguments -- "students ARE lazy" -- I refuted them by re-asserting Price's opinion: no, they're not; it's all about context.

Now, I can reshape what I have written around a thesis that I can establish early in the essay. I can also see that my thesis is not going to be a huge multi-part creation, but I am purposefully NOT writing it here because I want my students who chose to read this content to create their own thesis statements.

Some final thoughts for my classes.

THE FUN GAME: I am not editing this entry before I publish it. Can you help me? If you find a typo, let me know. If you find an error, let me know via the comments. Even if you're not my student, let me know. After all, I shared such corrections with this YouTuber the other day who used the word "less" when she needed to use "fewer," and she's supposedly an English teacher. Nobody's perfect. We're all just flawed humans.

ENGLISH 101: Mostly, the material I wrote here fits your assignment best as you are making an argument essay that agrees with Price, disagrees with them, or find a middle ground of combined agreement and disagreement. I have found that I agree. Honestly, I wasn't sure before I started the free write. My work here mirrors your own and could be your process. Observe the power of the first draft free writing exercise. Now, do you own thing.

ENGLISH 102: I did not expressly address rhetorical triangle in this free write. Your task is different than those of the 101 students. You are analyzing Price's use of rhetorical triangle not arguing whether you agree, disagree, or a bit of both. I am not going to produce a free write for you, though I will describe rhetorical triangle in a video for you. Pathos should be easy. Price appeals to pathos A LOT. Do they reason? Do they prove themselves credible via ethos and establish ethos via those they reference? Price is a social psychology professor and as such has some instant credibility with those credentials. Look then at how they express ideas. Do they seem credible? Trustworthy? Authoritative? How are these values established or fail to be established?

Here endeth the lesson.

Thanks for reading today's blog.

Stay tuned for other blogs, like tomorrow's WEEKLY HODGE PODGE and feel free to explore the almost 1900 other entries so far: see the categories along the right side of the page.

Hey Lower Columbia College STUDENTS! @LowerCC has some great resources for the #Spring term. https://t.co/ndHIQsuUCN#CollegeStudent #collegelife #cowlitzcounty pic.twitter.com/gtjSEKnlPC— Cowlitz DEM (@CowlitzDEM) April 15, 2020

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2004.22 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1754 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

3 comments:

Reading Laziness Does Not Exist changed everything for me during dissertation season. I wasn’t lazy I was overwhelmed. That insight led me to seek help and Pay for Online Dissertation support. It wasn’t about quitting, but finding guidance to keep going without burnout. Asking for help was my turning point.

Hi Alannah, thanks for leaving a comment on my blog!! I am happy to hear about your choices with your dissertation completion. Asking for help is the second cousin of saying no, both of which are powerful in managing work load, motivation, and stress. I assume you finished your dis? Thanks so much!!

Post a Comment