A Sense of Doubt blog post #2211 - Various links raided from ENO - MUSICAL MONDAY for 2103.08

This is Brain Eno's Twitter account: https://twitter.com/dark_shark?lang=en

"Understanding is simple. Knowing is complicated." - Robert Fripp #quote

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 7, 2021

Brian Eno: Here He Comes - from his 1977 album, Before And After Science https://t.co/LYg6lEeeBt

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 7, 2021

Roxy Music performing on the BBC's Top Of The Pops, March 15, 1973 by Watal Asanuma #glam #BrianEno @bryanferry @philmanzanera pic.twitter.com/me0yieuck4

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 7, 2021

David Bowie: The Future Isn't What it Used To Be in NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS September 13, 1980 #interview #BrianEno https://t.co/5VuearYaDf pic.twitter.com/t2SUUj1ecH

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 7, 2021

Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy): How Brian Eno Plotted Art Rock's Future https://t.co/PZWpTXlSEV pic.twitter.com/8Oqmtuav4H

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 7, 2021

Sonic Healing: Exploring The Restorative And Spiritual Qualities Of Music #Laraaji https://t.co/Rtnq3Qfklx pic.twitter.com/Mjiuh6MXwK

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 7, 2021

Brian Eno: Oblique Strategies in SHINDIG! October 2017 https://t.co/thoDYtmjK7 pic.twitter.com/LP2ZJaeka6

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 6, 2021

Brian Eno: City Of Life - his 2020 track previously available only as a 7" vinyl single included with the i.Detroit book; to listen, download the free i.Detroit app and point it at the book cover (it also works with a picture of the cover) #iPhone https://t.co/Ls5cZ0933U pic.twitter.com/lM9b7P7L0L

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 6, 2021

Remembering Miriam Makeba, born on this day in 1932 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Here she is performing “Qongqothwane” in Kinshasa in 1974. This performance took place at the Zaire 74 music festival that accompanied the Rumble in the Jungle boxing match. pic.twitter.com/nB8YKfVJVe

— Dust-to-Digital (@dusttodigital) March 4, 2021

Seeing Sound: The Effect Of Music On Your Mind https://t.co/hjx1joFT4y pic.twitter.com/73FVac1084

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 6, 2021

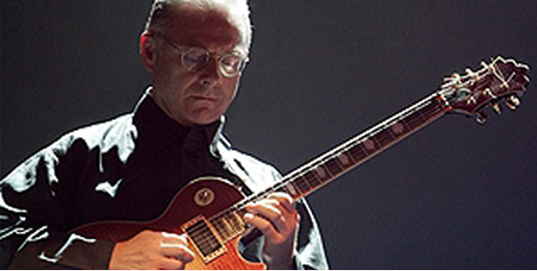

Robert Fripp, 1982 #KingCrimson pic.twitter.com/M7QjtmATHX

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

Robert Fripp: Music For Quiet Moments 45 - Elegy (Paris 22 Sept 2015) https://t.co/VazB6Ctres

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

Eye To Eye With Brian Eno in SCIENCE FICTION EYE Summer 1993 #interview https://t.co/C6pyFAVE4c pic.twitter.com/1zM4eWdt8F

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

Joni Mitchell: Fear Of A Female Genius https://t.co/W2PtrYOk0N pic.twitter.com/pgXtmbcSgD

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

Ralf Hütter reviews Kraftwerk's albums #interview #electronicmusic https://t.co/MRODFkaFfh pic.twitter.com/IV4xyQhl7S

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

David Bowie's Albums Ranked From Worst To Best #list https://t.co/bbKE1MjXg0 pic.twitter.com/Zpf9aaCWwG

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

Brian Eno Against Interpretation in TROUSER PRESS August 1982 #interview https://t.co/wj7X803f2g pic.twitter.com/17FX5ZRx5u

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 5, 2021

Brian Eno in FLUX February/March 2007 #interview https://t.co/yWJg2yBllv pic.twitter.com/utbVyQEd02

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 4, 2021

The Mystery Of People Who Speak Dozens Of Languages #hyperglot https://t.co/VlvOCjYJpe pic.twitter.com/jnxZbE7M4p

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 4, 2021

Brian Eno: St. Elmo's Fire - from his 1975 album, Another Green World; guitar by Robert Fripp https://t.co/WwOCti0vaN

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 3, 2021

The Studio As Compositional Tool by Brian Eno in DOWNBEAT July 1983 https://t.co/uK2bt6Wudt pic.twitter.com/r3nnHHJQBr

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 3, 2021

11 Killer Albums Brought To You by Brian Eno https://t.co/gmdCx5xQrI pic.twitter.com/hhmLanrJ9o

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 3, 2021

Oblique Strategy of the Day... #BrianEno #PeterSchmidt pic.twitter.com/R0JroOAyFy

— Brian Eno News (@dark_shark) March 8, 2021

https://www.seren.bangor.ac.uk/arts-culture/music/2021/02/13/my-life-in-the-bush-of-ghosts-and-the-history-of-sampling/

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts and the History of Sampling

BY STEPHEN OWEN ON

ME AGAIN....

Apparently, Robert Fripp started releasing ambient soundscapes weekly, and I am just now learning about it when he is almost done with his 50 week run.

Can you say future playlist??

YES...............

Robert Fripp - Music For Quiet Moments 42 - Glisten (La Spezia 28 Jun 2006)

2,657 views•Premiered Feb 12, 2021

Robert Fripp's "Music for Quiet Moments" series. We will be releasing an ambient instrumental soundscape online every week for 50 weeks. Something to nourish us, and help us through these Uncertain Times.

|

| https://www.dgmlive.com/robert-fripp |

The Road To Graceland

by Robert Fripp

I

Music is a process of uniting the world of qualities and the world of existences, of blending the world of silence and the world of sound.

In this sense, music is a way of transformation.

What we do is inseparable from how and why we do what we do.

So, the transformation of sound is inseparable from a transformation of self.

For example, we attract silence by being silent.

In our culture, this generally requires practice.

Practice is a way of transforming the quality of our functioning, that is, a transformation of what we do.

We move from making unnecessary efforts, the exertions of force, to making necessary efforts: the direction of effortlessness.

In this the prime maxim is: honor necessity, honor sufficiency.

II

When we consider our functioning as a musician, that is, what we do in order to be a musician, we find we are considering more than just the operation of our hands.

The musician has three instruments: the hands, the head and the heart, and each has its own discipline.

So, the musician has three disciplines: the disciplines of the hands, the head and the heart.

Ultimately, these are one discipline: discipline.

Discipline is the capacity to make a commitment in time.

If the musician is able to make a commitment in time, to guarantee that they will honor this commitment regardless of convenience, comfort, situation and inclination of the moment, they are on the way to becoming effectual.

An effectual musician is a trained, responsive and reliable instrument at the service of music.

III

So, practice addresses:

1. The nature of our functioning; that is, of our hands, head and heart.

2. The co-ordination of our functioning; that is our hands with head, our hands with heart, our heart with head, and in a perfect world, all three together in a rare, unlikely, but possible harmony.

3. The quality of our functioning.

IV

It is absurd to believe that practising our instrument is separate from the rest of our life.

If we change our practice, we change our lives.

Practice is not just what we do with our hands, nor just how we do what we do, nor why we do what we do.

Practice is how we are.

V

A practice of any value will be three things:

1. A way of developing a relationship with the instrument;

2. A way of developing a relationship with music;

3. A way of developing a relationship with ourselves.

So, the techniques of our musical craft are in three fields: of playing the instrument, of music and of being a person.

I cannot play guitar without having a relationship with myself, or with music.

I cannot, as a guitarist, play music without having a relationship with myself and my guitar.

And, by applying myself to the guitar and to music, I discover myself within the application.

VI

A technique simulates what it represents, and prepares a space for the technique to become what it represents.

For example, the manner in which I live my life is my way of practising to be alive.

There is no distance between how I live my life and how I practice being alive.

VII

Once a quality is within our experience, we recognise its return and may allow its action to take place upon us.

But how and why it is present, or comes to visit, is rather harder to describe.

If this quality is present with us, description becomes easier: we describe the world in which we live.

If we live in the way of craft, the craft lives in us; as we describe this way, the craft reveals itself through us.

Any true way will be able to describe itself through its craftspeople.

VIII

The quality we bring to one small part of our life is the quality we bring to all the small parts of our life.

All the small parts of our life is our life.

If we are able to make one small act of quality, it wiil spread throughout the larger act of living.

This is in the nature of a quality - a quality is ungovernable by size and by the rules of quantity: a quality is ungovernable my number.

So, one small act of quality is as big as one big act of quality.

An act of quality carries intention, commitment and presence, and is never accidental.

IX

Once we have an experience of making an effort of this kind, we may apply this quality of effort in the other areas of our life.

The rule is: better to be present with a bad note than absent from a good note.

When our note is true, we are surprised to find that it sounds very much like silence, only a little louder.

X

If music is quality organised in sound, the musician has three approaches towards it: through sound, through organisation, or through quality.

The apprentice will approach the sound, the craftsperson will approach the organisation of sound, and the master musician approaches music through its quality.

That is, the master musician works from silence, organises the silence, and places sound between the silence.

XI

Where we are going is how we get there.

If where we are going is how we get there, we are where we are going.

If we are where we are going, we have nowhere to go.

If we have nowhere to go, may we be where we are.

XII

Music is a benevolent presence constantly and readily available to all.

May we trust the inexpressible benevolence of the creative impulse.

|

| https://www.vice.com/en/article/mbd8nx/brian-eno-best-songs-guide-playlist-essay |

So you want to get into: 70s Rock Eno?

Playlist: Roxy Music, “Virginia Plain” / Roxy Music, “Ladytron” / “Baby’s on Fire” / “The Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch” / “Here Come the Warm Jets” / “Third Uncle” / Burning Airlines Give You So Much More” / "Taking Tiger Mountain” / “The Big Ship” / “In Dark Trees” / “St. Elmo’s Fire” / “Golden Hours” / “King’s Lead Hat” / “Spider and I” / “No One Receiving” / “By This River” / “Been There Done That”

So you want to get into: Ambient Eno?

THE DESCENT OF MAN

Loved by Bowie and Iggy, post-punk antagonists Devo went from heroes to zeros in just twelve months. Now they're back. "We were right all along," they tell Andrew Perry.

November 1977. Devo are playing Max's Kansas City, weirding out the New York punk set with their twitchy robo-attack and lyrics about mongoloids and de-evolution. As they wind up their first set of the evening to baffled applause, a gaunt figure strides after them into the dressing room. An hour or so later, Devo return to the stage, and David Bowie (for it is he) takes the microphone to introduce them.

"He goes, 'This is the band of the future!'," frontman Mark Mothersbaugh recalls today, "and, 'I'm going to produce them this winter in Tokyo.' We're like, Wow, we're sleeping in a van, we don't have apartments at home, Tokyo'll be just fine!"

In the end, Bowie's accomplice at Max's that night, Brian Eno, produced Devo, out of his own pocket, at Conny Plank's studio near Cologne in early '78. They'd hang with Bowie, who took the train over from Berlin on weekends, between shoots for the Just A Gigolo movie, and on one occasion the band jammed for three hours with Bowie, Eno and Can's Holger Czukay.

During those whirlwind months, Devo's hipster credential's were immaculate. Neil Young cast them as an all-singin', all-dancin' nuclear waste disposal tean in his Human Highway movie. Burt Bacharach invited Mothersbaugh over for a writing session, Iggy Pop shacked up with them in Los Angeles and Richard Branson flew them to Jamaica in an effort to get John Lydon, freshly liberated from The Sex Pistols, to replace Mothersbaugh as their singer.

Yet by the end of 1978 the public were fiercely divided over Devo. For a fanatical few, they were visionaries, lampooning man's slump into capitalism and moronic slovenliness with steely veracity For others, they were new wave clowns with decent tunes. The UK music press loathed them for their cynicism. There were fractious interviews in which Mothersbaugh and 'chief strategist'/bassist Gerald Casale came across as anything but grinning fools. Even Eno daubed them "the most anally retentive band I've ever worked with".

For the ensuing twelve years, Devo were freakish outsiders who enjoyed one brief canter in the mainstream after their Whip It video became a staple on the fledgling MTV. Since their dissolution in 1990, however, their sound has come to seem prescient of '90s dance, and today's synth-heavy indie-rock.

Now, the post-punk era's most baffling collective have returned with their first record in two decades, unsettlingly entitled Something For Everybody. Their latest motto? "De-Evolution: A Prophesy Fulfilled".

When Devo landed in Britain in 1978 at the height of new wave, they may as well have arrived from Mars. They came, in fact, from Akron, Ohio, North America's heavily-industrialised rubber capital. Their mission was bizarre, even for a rock band: to refute Darwin's Theory of Evolution - the very bedrock of modern science - on grounds that Man was regressing, not evolving.

On the cover of their Eno-produced debut, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!, Mothersbaugh remonstrated at you in white lab coat, rubber gloves and swimming goggles. On the reverse, three shades-wearing gents with stockings on their heads barked back. These were scenes derived from a twelve-minute movie from 1975, In The Beginning Was The End: The Truth About De-Evolution, in which Mothersbaugh mimed Devo's manifesto song, Jocko Homo, to a medical class: "They tell us that we lost our tails / Evolving up from little snails / I say it's all just wind and sails!"

The movie, which won the Best Short Film award at the 1976 Ann Arbor Film Festival, was soon seen on America's independent cinema circuit, and thus Devo's infamy rose. The ideas contained therein, however, were not fired off by frustrated teenage punks, but stretched back to the final days of the hippy movement.

Mothersbaugh had met Casale in 1969, while studying at Kent State University, ten miles from Akron. "[Gerry] saw some stickers I'd printed up of astronauts holding a potato, and an astronaut puking on the moon," remembers Mothersbaugh. "I'd been sticking them on fire hydrants, glass bookcases and portraits of school presidents. He looked me up. He was a couple of years older, but we started working together as visual artists."

Their world was turned upside down, when, in April 1970, the Ohio National Guard opened fire on anti-Vietnam protesters at Kent State, killing four, and wounding nine. Casale witnessed the shootings. "It was the day I stopped being a hippy," he says.

"It wouldn't be overly dramatic to say the shootings were Devo's starting point," adds Mothersbaugh. "School was closed for four months, so Gerry would come over to my house, and we'd write music, and talk about politics, technology, Ohio's crumbling industry. Our conclusion was that technology wasn't inherently bad, the problem was the human mind."

Together, Mothersbaugh, Casale and friends formulated their philosophy, based on an anti-evolutionary pamphlet from 1924 by one B.H. Shadduck, titled Jocko Homo Heavenbound. "We were talking about all this for years," says Casale, "then someone found a Wonder Woman comic, [where] a mad scientist had this chamber, where he pulls the lever and turns a guy into a monkey. The lever went from 'Evolution' to 'Devolution'. We thought, That's it, there's the word for it."

Mothersbaugh and Casale made their public debut at Kent State's Creative Arts Festival in '73. The band, provisionally titled Sextet Devo, was fleshed out with their own brothers, plus a hired drummer and singer. "It was hard to get people to be in the band with us," Mothersbaugh admits.

YouTube clips suggest proto-Devo was pitched between Roxy Music, Soft Machine and improvised theatre. By day, Casale worked in a janitorial supply store where, in a catalogue, he saw a uniform tailor-made for Devo: A suit made of plastic-coated paper. Cost: Five dollars.

"We wanted to present a unified force," Casale explains. "We thought that had more power; it was sexy, in a different way."

They also dreamt of opening Club Devo, Akron's answer to Warhol's Factory, fitted out with sinks and plumbing fixtures from Casale's catalogues. "From the beginning, the whole idea of Devo was multi-media," he says. "We originally intended to make a feature film, with hired actors, and stories about the devolved world. The music would drive the film, and if it succeeded, we thought we could send out half-a-dozen Devos around the country to play - a franchise like the Blue Man Group."

For a year or so, they attempted to pass themselves off as a covers band on Ohio's bar circuit but were trapped in a pitiful economy, so Mark and Gerry opened up their own graphic design company. Stumping up three thousand dollars, they made The Truth About De-Evolution with fellow Kent State alumni Chuck Statler, who had become an ad director in Minneapolis. By spring '77, after winning their Ann Arbor award, they landed gigs at CBGB and Max's. They demo'd about twenty songs, including such lost delights as I'm A Potato (And I'm So Hip), and Midget. When Iggy Pop's solo tour passed through Cleveland, Devo passed their demos on to Bowie. Against all odds, he and Iggy became somewhat obsessed.

Conny Plank's studio in rural Neunkirchen was the hub of Krautrock's hi-tech activity, home of Neu! 75 and Kraftwerk's Autobahn. Iggy and Bowie were certainly monitoring this site of future-sounds while making The Idiot and Low in Berlin, while their pal Eno cut numerous records there in the mid-'70s. When Bowie's film commitments ruled him out of producing Devo, Eno set about recording their debut album himself.

On paper, both parties shared much, from their similar names downwards. In keeping with their chemical-plant garb, Devo developed a robotic sound, with human spasms. Following on from Jocko Homo, their repertoire highlighted sundry aspects of man's decline, such as sappy romance, religious supplication, burger cuisine and rock'n'roll heroism, riffs stolen from I Wanna Hold Your Hand, and a mechanical reading of The Rolling Stones' Satisfaction - '60s pop mangled according to de-evolutionary logic. So very Eno... surely. Mark Mothersbaugh recently found a photograph of himself and Eno standing by a lake in Neunkirchen, holding hands. Such bonhomie, he concedes, was not representative of the album sessions.

"We came in knowing what we wanted the record to sound like, before he got involved," says Mothersbaugh. "He wrote all sorts of synthesizer tracks, and did tape loops, and sang vocals on every single song. When it came to the final mix, we'd all be standing in the studio, then just as the mix would start, one of us would reach over, and just slowly slide down the fader on the Brian Eno track, and the mix would proceed without his input. We'd be looking straight ahead, acting like nothing happened, and I could feel his eyeballs going into the side of my head, like, 'What the fuck are you doing?'"

Mothersbaugh told Eno that the producer's lyrics were "daft". He also stole a blank card from Eno's 'oblique strategies' pack, drew a rat on it, and stuck it in a mousetrap in the corner of the studio. "I thought they were silly," he says, "like fortune cookies, but I wish I hadn't done that. We were very insular, because right from the beginning, people didn't get what we were saying. Our early gigs ended as confrontations and fist fights, so that always gave us reason to be defensive."

Mothersbaugh is contrite because the band were able to shop around for a deal with a ready-made, Eno-franked LP, signing long-term to Warners for AMerica, and Virgin in the UK. But Devo were still commercially doomed. A legal tangle over Transatlantic rights left Warners out of pocket and less keen to promote their new act. Warners also had to shell out when the band's own college buddy and road manager, Bob Lewis, sued them for his part in establishing De-evolutionary theory.

Branson's legendary gambit, meanwhile, to supplant Mothersbaugh with Lydon, suggests he had little faith in the band's longevity. Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! - its title based on the monkey-man chant from Island Of Lost Souls, the 1933 adaptation of H.G. Wells' Island Of Dr Moreau - reached Number 12 in the UK charts, but, after initial Bowie-related hype, Devo were soon viewed with disdain, Sounds asserting that the album "breaks about as much new ground as The Darts' It's Raining".

Even in the pre-political correctness times, the song Mongoloid felt just too near the knuckle, especially from an apparently comic rock band, who wore flowerpots (AKA "energy domes") on their heads, and often appeared wrapped in latex, wearing dildos, baby masks and fake breasts.

"Touring England, people were spitting all over us," remembers Casale. "We were glad we were wearing yellow plastic suits, which you just throw away after the show. At Eric's in liverpool there was a metal mesh, floor-to-ceiling on a wooden frame, between you and the audience. We started our set, and they all smashed themselves against the fence as hard as they could, yanking it back and forth like monkeys, and hawking and screaming. Wow!, we thought, this looks like a Devo movie. This is de-evolution!"

At some shows, Devo created more antagonism by appearing as their own support act, Christian Rock band Dove (The Band Of Love). They were flying way over people's heads, and their career suffered. Their next two albums dramatically under-performed until, in 1981, Whip It - one of their most deviant ditties - was picked up by radio in florida, and became a US hit. "MTV was experimenting in three cities," says Casale, "and we had made five videos by that point. They begged us to let them have our videos because they didn't have any content. Then as soon as they went national, they tied their playlist to Top 40 radio, and canned Devo. After that, the three-musketeers camaraderie of 'one for all and all for one' started to erode. You had all the evil little weasels coming up and going, 'You're really the band, why don't you just do a solo record?' Then drugs entered the picture. Mark would be with his girlfriend doing ecstasy, while I was at concerts and parties doing cocaine. Those two states of mind don't blend well.

"I started directing videos for other bands, but we got enticed into this deal with Enigma Records, a huge mistake. Mark was disinterested after that. If you have a two-cylinder bike, and one of the cylinders isn't working, you're not going anywhere."

In the long run, Devo - the band, the sound, the philosophy - was indestructible. Mothersbaugh applied his talents to writing music for TV, adverts and films including Pee-Wee's Playhouse, The Rugrats, and Wes Anderson movies. His company, Mutato Muzika, employed Devo's Bob Casale and Bob Mothersbaugh, and after a few frosty years, he and Casale buried the hatchet. Devo started playing occasional shows circa '95 and producing ads for Dell computers, and Honda. Momentum towards a comeback record has been gradual, but unstoppable.

"You couldn't pick a worse time," says Casale with a chuckle, "with the economic meltdown, the implosion of the record business, and no new viable business model to replace it. People feel like they shouldn't have to pay for music, everything's on an iPod shuffler, content is meaningless..."

De-Evolution: A Prophesy Fulfilled?

Mothersbaugh smiles: "It's a bittersweet thing to have to say but it seems like the last thirty-five years have proved our theories to be, unfortunately, right on the money."

The Music Of Our Spheres

Stream Brian Eno's new album, 'For All Mankind'

Mojo JANUARY 2016 - by Andrew Male

LAURIE ANDERSON

A Midwest violinist-turned-New York performance artist, O Superman shot her to fame. Now, as Laurie Anderson puts her philosophy of life on film, and comes to terms with husband Lou Reed's death, she says "All we have is now."

"I'm sorry," says Laurie Anderson, "When I'm away from my home I kind of take my office I with me." She is sitting in a high-backed designer leather chair in the corner of a cluttered Warner Records anteroom, scrolling through the e-mails on her phone. Tonight she has a few hours off and might take herself to Foyles bookstore, but for the rest of the time she'll be stuck in what she calls "the film festival rut: screen your film, talk about your film..." as she promotes Heart Of A Dog, a funny, sad, lyrical cine-essay that moves from ruminations on the death of her much-loved rat-terrier Lolabelle to reflections on storytelling, language, identity, memory and loss.

Anderson's tour-look is relaxed and Eastern, dark silk jacket, linen trousers and trainers, and her words are delivered with a melancholy lightness, her eves wide and bright, her smile puckish, suggesting that it's no biggie, this European festival rut, just something that goes with the job, after thirty-plus years as a multimedia performance-art avatar, monologist and recording artist of rare and strange beauty.

It's the same soothing yet questioning tone we first heard on Anderson's dream-like eight-minute 1981 single O Superman - debuted on John Peel's late-night BBC Radio 1 show - that led to a signing with Warner Brothers Records, briefly propelling the then thirty-three-year-old New York-based performance artist into a heady world of pop stardom. The fame eventually settled down into something more convenient, but the song never really went away. It was under the surface of albums like 1994's Brian Eno-produced Bright Red, in which Anderson attempted to comprehend America's war in the Gulf, and reappeared in her live New York performance on September 19, 2001, where lines such as "Here come the planes / They're American planes" hummed with their eerie prescient power, confirming what Anderson has always said, that "we're all still stuck in the same war". And it recurred in the short evening performances that followed her most recent art installation, Habeas Corpus, at the New York Armoury in October. Here, a live video image of Mohammed el Gharani, one of the youngest Guantánamo detainees, was projected onto a sixteen-foot-high sculpture of a seated human form the size of the Lincoln Memorial.

The drone score for Habeas Corpus was composed by Lou Reed, Anderson's former husband and partner for over twenty years before his death in 2013, and it's Lou and Habeas Corpus and the new film that our conversation keeps resetting to today, amid matters of the past and the future, bearing out the message that Heart Of A Dog plays out on, bound up in a Reed song from 2000, Turning Time Around. "He gets the last word," says Anderson, "and it's right to the point: don't go looking to the past with your regrets, don't go to the future and how much better it's going to be. All we have is now."

How did Heart Of A Dog come about?

It was a commission from Arte, the French/German TV channel. They said, "Can you make a film about your philosophy of life?" I said, "I don't have one. And if I did I would not put it in the shape of a film and make you watch it." Well, the producer had come to [Anderson's 2012 performance piece] Dirtday! and he said, "You had those stories about your dog. Put those in," and I said, "OK." Then I added a few related stories, then asked a few questions about how you tell a story, and what happens when you repeat your story, or forget your story, and then, in the end, it's my philosophy of life. They've tricked me into it.

It references The Tibetan Book Of The Dead a lot...

I began to study The Tibetan Book Of The Dead after Lolabelle died. It became very personal because it's all about what I do as an artist anyway. How to be aware. That's it. You're not even asked to believe anything particular. That's an amazing approach to things. My family's religious background was one half Southern Baptist, the born again stuff, and the other side was Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant, which was just a be-nice-to-people religion. That's it, just be nice. So, I got a little smattering of different approaches.

The film is also a meditation on loss.

It's about death in general. I have only recently started to count the number of people who die in this film. But even though love and death are themes, the actual theme is story construction, like why do we tell stories and where is it that language becomes fallible and images have to take over. That's one of the reasons why the second story in the film is my mother's deathbed speech. She was a very proud person and very formal, so she waited on her death bed until all eight kids were there and she almost sort of stepped up to the microphone and said, "Thank you all for coming," and then she gets a little distracted and starts talking to the animals she sees on the ceiling, and in this way that you can watch the words just sort of ripping apart. It was one of the most moving things I've ever seen, because language is completely inadequate to the task of saying goodbye.

I don't want to make a trite leap, but this film ends with a Lou Reed song, the sound of Lou's voice...

That's not a trite leap. He didn't use any reverb on his voice in that song and it's very, very real. Very conversational. Very engaged. And I loved that he made that equation of love and time being the same thing.

How did growing up in the Midwest, in Illinois, shape the stories you told?

Well, Heart Of A Dog is also a film about the sky, as it represents freedom and fear. And in Habeas Corpus, the whole Armoury is turned into the night sky. It became a context for how we see our own freedom because it was for me as a child. A very, very flat place, with a dome of sky, that was the dominant thing where I grew up and even now I like really super-flat places like Holland. I see mountains and I feel hemmed in. Other people go, "That's nondescript." I say, "What do you mean? It's sky-rich."

You came from a big family, seven siblings including twin brothers. In Heart Of A Dog you tell a story about wanting to be noticed, of doing a back flip off the swimming pool high board and missing the pool. You broke your back, you were paralysed, doctors said you'd never walk again, and it took you two years to recover...

Yeah. I was the second oldest and so my job was to take care of a lot of them. It shaped my life, like anybody who has that. While I was in the middle of making Heart Of A Dog my older brother sent me these cartons of old eight millimetre film. Family films. I was really busy so I just reached in and transferred a couple and suddenly there's my little brothers in a stroller, there's me ice skating, there's the lake, the island, oh my God. I called my brothers and said, "Remember that time I almost drowned you, when the stroller went under the ice?" "Yes, we do!" They're twins so they have like an outboard brain and they were two and they remember that. And they said, "You're not going to put that in the film are you?" I said, "Do you mind?"

Ice skating is central to one of your earliest performance art pieces, Duets On Ice. You wore ice skates frozen in blocks of ice and played a duet with yourself on a violin where the bow hair was audiotape and the strings were a tape head. The piece ended when the ice melted...

Ice skating and frozen lakes was my life as a child. I came from a frozen world. Every winter there was snow up to the height of the ceiling, and so much of my life was being dazzled by the sparkle of winter. That and the sky are the things you carry with you.

You were studying classical violin from the age of five...

Yeah. My parents wanted a family orchestra.

The Midwest Von Trapps?

Hur. Not quite. Let's not go that far. We didn't... oh, we did wear matching outfits! What am I saying? Oh dear. We wore navy skirts and red sweaters. Nice.

You were an undergraduate at Mills College in California which housed The San Francisco Tape Music Center, home to Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, Terry Riley... Did your world cross over with theirs?

When I was there it was more Pablo Casals in residence. I was doing chemistry. I was pre-med. I had stopped violin. I realised I wasn't really good enough. I liked the idea of medical school a lot but I was only one semester at Mills. I hated it. I hated every minute of it because you had to wear a long skirt to dinner on Wednesday and that put me off the whole thing. I was just disgusted by that. I'd gone to California to be as far away from the Midwest as possible, so then I just decided to go to New York instead and in the middle of studying chemistry and botany, I realised I actually liked doing the drawings more than I liked getting the information right. So I thought maybe painting is more for me.

One of your earliest performance pieces, from 1972, was the Institutional Dream Series, where you slept in public places to see if specific sites influenced dreams. Heart Of A Dog begins with the recounting of a dream. Dreams seem integral to what you do...

I trust that world. A whole lot of things come from that world. One of my favourite stories Mohammed recounts in Habeas Corpus is about a detainee they were interrogating and he told them about a dream he'd had where a submarine came to Guantaáamo to rescue everyone. Well, that night, Guantanamo Bay was filled with helicopters and ships, looking for the submarine that he had dreamed about.

That's so creepy. The CIA are looking for plots against them in our dreams.

We make plots in our dreams. It's an obvious thing to say, but many of our fears and hopes are expressed in our dreams. When you think of what you're actually talking about, it often has nothing to do with what's really going on. I put some really fast words up on the screen in Heart Of A Dog, [to represent] those words that go around in your head, that you never say. It's like talking to that person inside you, the silent witness, the person who's been there all the time, and to whom language sounds a little bit stupid. You're using them right now, as I am, as we're having this conversation, that silent witness is analysing it and thinking this, but not saying anything ever. That's why I wanted you to read this fast succession of unvoiced words. It's coming in a different way into your mind. I invented a computer program to do this, ERST. I don't know why I gave it a German name. I think it stands for Electronically Reproduced Simulated Text, or something horrible like that.

You've always done this, inventing new strange instruments like the tape bow violin or the talking stick. Is this always a means to an end -1 want that sound that doesn't exist - or an end in itself - the beautiful-looking art-piece?

A little bit of both. They're a bridge for me between sculpture and performance. They're hybrids. My work often is. Habeas Corpus is sculpture, performance and film. I like weird hybrid forms. I've never really fit very easily into a category because they have these uncomfortable elements that don't fit. I'm not trying to colour outside the line on purpose, it's just... it's interesting.

In 1976, you were briefly in a band with Arthur Russell.

He was in my band. Cello and drums. I loved Arthur's music. We got along really well. We didn't think that it was because we were [both] from [the Midwest]. It's funny what happens when an industry dies, a record industry. It has crumbled, that empire, and with it the ability to sit around for a year and make a record. There isn't really a substitute for spending that amount of time on something. You could do big things. But I try not dream of that. Just go and make something really simple with a pencil.

I also read you were Andy Kaufman's straight man at the end of the '70s. When he got to that part of his show where he said "I won't respect women until one of them comes up here and wrestles me down." That was your job, to wrestle him.

Yeah. And he wasn't pretending. It wasn't scary. Maybe metaphorically scary. I don't think I was ever really scared. I think if he thought he was going to hurt anyone he would have absolutely stopped. There was metaphor in everything Andy did. On the other hand, he was very hardcore and believed in everything he did. He was a kind person, and funny, but he loved using doubt and violence and fear and confusion. He was a master of all of that, of creating that and bringing it out. We'd go on field trips to Coney Island to test out his theories. We'd go on rides like the Roto-Whirl, where the bottom would drop out and plaster you to the side of the spinning cylinder, and right before the ride would start he'd be saying, "I don't think this ride is safe." People who were about to have fun on the ride, a lot of them got off.

You recorded your 1981 single O Superman through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and pressed up just a hundred copies. John Peel played it on Radio 1, you were signed to Warners and it went to Number 2 in the UK singles chart. Do you ever wonder what might have happened if John Peel had never played it?

I think I had a fairly anthropological interest in that. Or tried to. When you get something that you didn't dream of, it means a different thing than it would if you'd always dreamed of having it. I knew this would be dangerous if I wanted it to go on and on because this was a quirk of fate and it's like, even now, I'm the kind of artist who wants to get smaller rather than bigger. I don't ever want to open the Berlin office.

You perform O Superman during the Habeas Corpus evening shows. Those lines, "When love is gone, there's always justice. And when justice is gone, there's always force", really resonated with audiences. Similarly, when you played O Superman at Town Hall in New York City in the week after 9/11 and sang, "Here come the planes / They're American planes", you said you suddenly realised you were "singing about the present". Does it spook you out, how much that song continues to accrue meaning?

No it doesn't, because we're in the same war. Most people don't recognise that. And it's working kind of the same way. The same things keep breaking down, the same questions keep being asked. And force, justice and love are still major themes.

At the height of your popular attention, you made one of your biggest multi-media productions, the Home Of The Brave concert movie. There's so much going on in that film, so many people on stage... Were you trying to hide from pop stardom behind all that spectacle?

I'm not sure I wanted to hide. No. During that time, and part of it comes from being a snob, when I went out to Warner Brothers to do my eight record deal, they sat me down in a room and said, "I want you to meet the other artists," and there were these guys like (mimes slouchy, gurning, nose-pic king urchin) and I was like, Who are these guys? 'Artists' for me was like Duchamp. But they spoke about "the artists" with heavy quote marks around them. Wow, you're being so cynical. We're your marketing tools. We're not the artists.

On the other hand, Warners was an incredible label. They actually really liked singer-songwriters. They supported them. They supported me. They said, "We like your music and we'd like to put it out," and I thought, OK, why not? What is the downside of this? Plus, the other part of the snobbism was that I didn't like that artworks cost so much and I liked that anyone could buy a record. I got a lot of flak from the art world for signing with Warners. They were like, "You sold out. Why did you do that?" It only took about four or five months before it was called 'crossing over' and everyone did that. In the end I was happily floating between both worlds but I never quite belonged to either one.

One single from Home Of The Brave, Language Is A Virus (From Outer Space), was inspired by a line, a concept in William Burroughs' The Ticket That Exploded. Was he a big influence?

Definitely, because he really made me laugh. That guy was insanely funny. And dark. I toured with him and John Giorno on the club circuit in 1981 and we had a great time. It felt very vaudeville because Bill would always bring his cane and... wait a second... he brought guns. And he would go out and practise. In the back. That bothered me. That he liked guns, and that he didn't really like women. Those were the two things that put me off a bit. Otherwise, I loved him, because he was an old coot and hilarious and really cranky. And I have a real attraction to cranky people. I don't know why.

Am I allowed to mention Lou Reed at this point?

Oh, you are. You are. What makes you so cranky? I'm interested in that.

In 1991 you interviewed John Cage for a Buddhist magazine. Another influence?

More twins. Cage and Burroughs. Light and dark twins. I really fell in love with [Cage] in the last year of his life. He made a huge impression on me. So many old people are angry, bored and he was not like that for one second. He almost reminded me a little bit of the happiness of a dog, whose mouth is open, he's looking around, wow! He was dazzled by things, and that is probably the thing I most admire in humans, their ability to be dazzled. And he really was in weird circumstances. Merce [Cunningham] had left him, he's by himself, it's harder for him to go places... He said, "I can't pick up my suitcase." So I said. Til come with you!" I was so happy to spend time with him. He was beyond inspiring. His ability to see and appreciate the world as music, and as a completely finished artwork, I think about that all the time, and his ability to be in the present and not be worried about something or projecting something.

Tracks like Night In Baghdad and The Cultural Ambassador on your mid-'90s albums Bright Red and The Ugly One With The Jewels were direct responses to the Gulf War. That seemed to have a major effect on you. It was a multimedia war.

Well, all the wars. But, yeah, sure, it had its own music, its own graphics. It's like we've been saying, the one who gets the best focus is the one with the best story. Do you like the story, do you like the music that goes along with it?...

One of your biggest productions was 1999's Songs And Stories From Moby Dick. The album based on that show became something else entirely, 2001's Life On A String, and you later said, "If you ever get any idea about doing an opera based on a book you love, don't do it."

Yes, and I am so serious about that.

Did you get swallowed up by it?

Yes, just like a whale. I was the smaller fish. I was too worshipful. I loved it too much. That made me too shy and careful. You can't be shy and careful if you're going to carve up a whale. I wish I hadn't done that.

You seem to have this pattern though. After a huge project like that your next project is always stripped back, spare, simple...

Yeah. It's a question of energy more than anything else because I like to make these beautiful simple things. Like... I'm doing these drawings for this show in Switzerland and... It was in the middle of the summer and I was kind of in trouble from Habeas Corpus. I had to get some therapy because I couldn't get these pictures out of my head. Do you remember the first time you saw the pictures from Abu Ghraib? This combination of pornography and violence? What is that? And you just can't get those images out of your head? That's what happened to me.

One of your stranger commissions must have been when you became NASA's first (and last) artist in residence in 2003. How did that come about?

Just a phone call. Why they thought I would be good PR for NASA is beyond me. It was definitely a PR move to get NASA into the public awareness more. Behind that was this idea that its military applications had become dominant in the public imagination, that they were just making rockets and shields and weren't looking out any more so much as looking down and spying on people and creating fast weapons and that's very true. They didn't really know what a NASA artist-in-residence did, so I just became a fly on the wall looking at them.

You don't need NASA's budget to make art. You can make visionary art, dangerous art, with a pencil and paper. Artists tend to forget that these days, especially now the Russians are in the market. You notice how many more works have gold dust or diamonds encrusted into the canvas. Extra added value - that's a nauseating development for me. But I got to poke around in the corners [at NASA] and any time you get to do that is great. This is what I love about being able to do what I do. Without war. I'd never have been friends with Mohammed, who's not an Al Qaeda operative but a goat-herder from Saudi Arabia. War gave me the chance to meet this person.

Was that the thinking behind 2003's Happiness? You prepared for that show by taking a job at McDonald's, working on an Amish farm, Zen river-rafting...

Yeah, get out of my rut. That's what I should do. I'm in a kind of rut right now. Do you have any good ideas?

Your work is about how you look at the world, and how that changes you. After Lou died you spoke very eloquently about his life and his passing. At the thirtieth Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction ceremony this year you said his death propelled you into "a magic world where you finally understand things that were complete mysteries up to that point."

Did I say that? Well, that's true. I have not rowed my boat back from that. I probably never will, because it's too wild, and I've met a lot of people who were suddenly very absorbed in a partnership, and then your partner is gone and part of you goes with it, but part of that partner stays too. It's a very, very weird thing to be part of and it becomes a very real thing. Also, when your partner is a really real person the way Lou... Lou is still, I have to say, a lot more real than many people I know because, he came to play. He was not goofing around.

What next?

Who am I? What am I? Those questions are always in the background of what I'm doing. And giant landscape paintings. I feel the need to make something enormous and still.

THE ANDERSON TAPES: ESSENTIAL LAURIE

THE FIRST ONE Big Science - A flinty distillation of United States I-IV, her eight-hour multimedia performance-art epic about the US military industrial complex, Anderson's major label debut is a surprisingly moving and groovy collection, somewhere between minimalist post-punk electronica and a comic Robert Wilson spoken-word opera about plane crashes and dreams of falling in post-war America. Also, US pop's love affair with Auto-Tune can probably be traced back to Anderson's eerily seductive use of vocoder on this long-player.

THE AMBIENT ONE Bright Red - "I learned something important when I worked on Bright Red," said producer, Brian Eno, recently. 'I said, What do I really like here? I really like her voice. So I just listened to the voice until I wanted to hear something else happen." As a result, Bright Red is Anderson's most spare and spooky album. Written in the wake of the first Gulf War, it is a hypnotic, unsettling listen, like some deep, long, waking dream on "this tightrope made of sound".

THE DIVERSE ONE Life On A String - Originally intended as an audio document of her vast, impressionistic 1999 performance-art piece, Songs And Stories From Moby Dick, Anderson's sixth studio LP became something else entirely: three numbers from Songs And Stories plus some of her most honest, emotional and stylistically varied compositions, including collaborations with Bill Frisell, Mitchell Froom and, on the sonically unsettling One Beautiful Evening, her boyfriend Lou Reed.

WE'RE NOT WORTHY

Jean Michael Jarre salutes Laurie Anderson's artistry - "For innovation in sound, Laurie has opened so many doors through the way she uses processed vocals and her different approaches. She's a linguist, a writer, a poet, a painter too and totally underrated as a visual artist. She is intellectual and animalistic at the same time, always evolving into those extremes.

https://thequietus.com/articles/05047-david-bowie-station-to-station-review-anniversary

Exploring Notions Of Decadence: Bowie's Station To Station, 45 Years On

Ben Graham , January 11th, 2016 00:02

Ben Graham takes a detailed look at the decadent path trod by David Bowie during the creation of Station To Station

Decadence is an appropriately mutable and ambiguous concept. It can be used to signify the most contemptuous approbation, to suggest rottenness, decay, wasteful amorality and an utter disconnectedness from reality and shared social values. Yet without any real change in its meaning, the word can also be used in praising terms to suggest an alluring glamour, a wild, intoxicating freedom from society's petty restraints and a sense of abandon and entitlement that is somehow admirable despite, or even because of, its obvious destructiveness. In some ways, decadence is about style over substance, and whether you view that as a sin; it's the difference of opinion between the socialist and the dandy, and many of us struggle to balance these two conflicting positions within ourselves all the time.

More than on any other Bowie album in a career built on exploring the theme from any number of angles, the idea of decadence is at the heart of Station to Station. If Young Americans, his previous album, had examined the post-Watergate rottenness infecting the once-great nation he'd recently adopted as his home, then on Station to Station he turns his gaze fully inward upon his own condition, and finds the creeping decay at work there too. It's a pre-punk album, not just chronologically (recorded in ten days at the end of 1975), but in recognising the hollow, bloated state of the rock aristocracy of which Bowie was a part, especially in contrast to the social upheaval and economic recession going on in the real world, wherever that was. Punk was a response from the kids on the street, but Bowie was part of the problem, and he knew it, tall in his room overlooking the ocean, staring out through a blizzard of coke and knowing it was all coming crashing down.

Ah, yes: cocaine. The proverbial Peruvian is all over this record, but not in an over-produced, airbrushed Rumours way. Station to Station is shiny but spare, harsh; it captures the jagged edge, the exquisite balancing act between the high and the comedown, and the sense of feeling hugely emotional at the same time as feeling completely numb and detached that is a typical symptom of fast white drugs (speed, E, coke). Similarly the intellectual grandstanding, paranoia and occultism, barely masking an inner desperation; having made a career out of wearing masks, inventing personas, analysing his emotions from a distance and then acting them out, Bowie seems desperate for a way out of his situation. Early in his career, under the influence of Lindsay Kemp, he made a short film called The Mask, in which a mime artist puts on a mask that then takes him over. By 1975 for Bowie the parable had come true. Lauded, wealthy, trapped in the social whirl of an affluent and fashionable Los Angeles jet set, reputedly existing on a diet of cigarettes, orange juice and cocaine and immersing himself in mysticism, conspiracy theories, the occult and an increasing fascination with right-wing ideologies, Bowie was fast becoming the epitome of the Decadent Man. Yet Station to Station is far from the work of an artist in decline. Rather, it extends the Philly funk of Young Americans into weirder, colder territory, and marks the beginning of the period of radical musical reinvention and rigorous introspection that would continue through the Berlin period and the more celebrated Low and "Heroes" albums.

Like the Duc Des Esseintes- the original Thin White Duke? – in Huysman's 1884 novel A Rebours, Bowie has become jaded beyond belief, too numb and sated to be moved by any but the most extreme sensations. So far gone, so alienated from his own feelings is he that what he craves more than anything else is an authentic experience. Eventually he would realise this by stripping away all artifice and moving to Berlin, but here he still attempts to contrive genuine emotion, to convince himself by dint of a bravado performance. As if acting on 'Young Americans' celebrated line, "ain't there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?" Bowie constructs the most grandiose of love songs, the most overblown, epic ballads, mouthing hollow romantic clichés as if, by saying the lines with enough simulated passion, he will actually come to feel them. And yet, of course, all of this is just a construct, too- he knows exactly what he's doing. It's not a cynical act, because the desire to feel remains genuine- in its way, this is as stark and troubled a record as anything from Neil Young's contemporaneous ditch trilogy, the musical polish and role-play only thinly veiling a soul on the edge, battling with addiction and paranoia and with what he, at least, genuinely believed were dark mystical forces just waiting to drag him forever into the abyss. "It's the nearest album to a magical treatise that I've written," Bowie has said, though perhaps a ritual spell of protection would be a more accurate description.

The album opens with the sound of a train. An old-fashioned steam train, chuffing from speaker to speaker and which always makes me think of Mr Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood- leaping ahead to Berlin, again - and then suddenly it isn't a train anymore, but something far more warped and alien, and here come those flat, clip-clop piano notes, the spidery beat and Earl Slick's strafing guitar feedback out of which a dragging, leaden riff slouches, some rough beast waiting to be born… But Bowie's vocal is anything but rough: silken, demanding, ridiculously theatrical yet eerily convincing. 'Station to Station' isn't about trains, despite being written while the notoriously aerophobic Bowie was touring America and Europe by rail; instead, it refers to the fourteen Stations of the Cross, which Bowie also equates to the eleven Sephirot of the Tree of Life in the Jewish Kabbalah- hence, "one magical movement from Keter to Malkuth," the songs most enigmatic lyric, which refers to the descent from the Crown of Creation to the Physical Kingdom, or from one end of the tree to the other.

This first section ends with a cryptic reference to Aleister Crowley's early, poetic fusion of pornography and occultism, White Stains. A classic of decadent literature, Crowley himself later justified this short work as follows: "I invented a poet who went wrong, who began with normal innocent enthusiasms and gradually developed various vices. He ends by being stricken with disease and madness, culminating in murder. In his poems he describes his downfall, always explaining the psychology of each act." It's not hard to imagine Bowie identifying with such a project, but before we have time to digest this, the whole song suddenly switches gear: not once, but twice, into hard, urgent funk with a proggy chord sequence, and then again, finally hitting that glorious plateau of a chorus and somehow staying there, like a never-subsiding orgasm, held impossibly aloft by Roy Bittan's driving piano, just so long as you don't look down- "It's too late!" –Slick kicks in with a wired, fiery solo, and then, "it's not the side effects of the cocaine- I'm thinking that it must be love," and we're still up there, somehow- it's a sustained, smooth-jagged coke high of a song, just keeping going, always up and on the one until it finally, inevitably fades out…

'Golden Years' is one of Bowie's finest middle-of-the-road moments, a mainstream soul-funk ballad with mass appeal but a seriously weird core. It comes on like a love song, but what is it actually about? "Nothing's going to touch you in these Golden Years (run for the shadows in these golden years)." It's opaque, impenetrable, all mirrored surfaces and shifting moods. Again, the incessant, almost proto-rap delivery, listing things to do, balancing aggressive positivity ("Don't let me hear you say life's taking you nowhere") with brittle paranoia ("run for the shadows…") is pure coke babble, riding on the bright mellow glide of the groove and the dark empty spaces beneath… nothing's gonna touch ya, move through the city, stay on top, all night long…

And Yet:

"In this age of grand illusion, you walked into my life out of my dreams..." What starts out sounding like a poignant love song suddenly becomes a doubting hymn, a tentative declaration of faith directed towards God above with no sense of irony or role-playing. That Lord's Prayer moment at the Freddie Mercury tribute concert is alarmingly prefigured, as the penitent gak fiend drops to his knees on the studio floor (and a sudden shaft of light throws a shadow of a cross behind a conveniently positioned mike stand…). This song's origins apparently lie in Bowie's experiences filming The Man Who Fell to Earth, where certain unspecified dark doings on set led him to fear for his immortal soul. Working with Nic Roeg seems to have this effect on people: James Fox had a breakdown, found God and quit acting for years after working with the director on Performance, while Jagger was haunted by the role of Turner for years afterwards. Like Jagger in Performance, Bowie essentially played himself when portraying the alien visitor Thomas Jerome Newton, but soon found the role taking over his "real" life instead. Bowie began wearing a silver crucifix around his neck to protect him from occult influences, and 'Word on a Wing' finds him reaching out for some kind of belief that remains somehow just out of reach. The line "it's safer than a strange land" draws parallels between The Man Who Fell to Earth and Robert Heinlein's cult SF novel Stranger in a Strange Land. Throughout the early seventies Bowie spoke often of starring in a film adaptation of this book, about a messianic Martian who arrives on Earth, comes into conflict with the established church and is ultimately assassinated- obvious shades of Ziggy- but here Bowie seemingly renounces such Nietzschean self-determinacy in favour of the foxhole of orthodox Christianity.

'TVC15' provides light relief, of a sort; nobody's favourite Bowie song, though the author seems to be having fun, and check the live version for a cringe-inducing example of rigorously-rehearsed spontaneity and looseness, a forced fake bonhomie among the band. It's hard to say why it doesn't work; certainly the brittle, cokey-hokey rush of words and the spiky piano jabs are in keeping with the rest of the album, but is it too frivolous-sounding in such heavy company? Or is the joke just too oblique for most listeners to get? Moving swiftly along, 'Stay,' apes '1984' from Diamond Dogs, which itself purloined that dirty, funky wah-wah guitar sound from Isaac Hayes' 'Shaft'. Somehow though, the studio version never takes off for me, and this is one case where the live Nassau Coliseum version is far superior.

And so finally we come to 'Wild is the Wind', and who would've thought an old Johnny Mathis number would inspire Bowie to perhaps his finest ever recorded vocal performance? Also his most over the top and ridiculously affected, of course- try doing this one in karaoke and see if you can get away with it- but it's the vocal that carries the song completely, turning what could have been a fairly plodding number into an epic finale to an already massively melodramatic album, on the back of little more than a strummed acoustic guitar, extremely spare bass and drums and some heavily-treated but low-key electric picking. Bowie's vocal builds and builds, as the verses just repeat the same simple chord sequence, broken up by two deadened drum rolls that always make me think of Animal from the Muppets- until it finally just fades out, leaving you completely drained. "Don't you know you're life... itself?"

And that was it. Just six songs long, yet bestowing one of Bowie's most enduring personas- The Thin White Duke, part Thomas Jerome Newton, part barking mad aristocrat from imperial Europe. Barely suggested on the album, he came to life on the subsequent tour, in front of a set inspired by Albert Speer and Leni Riefenstahl, in white shirt, black dress trousers and waistcoat, hair slicked back, frighteningly pale and thin, jerking across the stage in clipped, precise movements. An aging Ziggy, messianic fervour curdled into megalomaniac zeal, the scorned saviour turned armchair dictator, still mouthing hollow clichés of love and piety while quietly plotting bitter revenge. Bowie would have us believe that it was the Duke, not him, who gave the Nazi salute at Victoria Station and blathered on about how England would benefit from a Fascist dictatorship. And certainly, Nazism is one end product of a curdled, decadent romanticism, and a neo-Christian fascination with the occult, taken to irrational, nationalistic extremes. Personally, I'm prepared to accept that it was the side effects of the cocaine after all, and leave it at that. Happily, the album's cold, claustrophobic funk and sense of dramatic tension would prove more enduring than the obsessions of its decidedly dodgy central character. Next stop- 1979, and early albums by Magazine, Simple Minds, the Banshees and Bauhaus, and many others in the post-punk, European canon. Station to Station, indeed.

Ben Graham on the reissue package

One might even suggest that in an era of enforced austerity, global recession, massive cuts in public spending, looming unemployment and an increasingly obvious gap between the haves and the have-nots, it is an act of decadence on EMI's part to be releasing an individually-numbered 5-CD, 3-LP and DVD box set (also including 24-page booklet, poster, replica fan club pack, press kit, backstage pass etc- “the ultimate fan's experience”) which, despite retailing for around £100, adds very little in musical terms to the original album which the target market will, without exception, already own.

Not that your humble reviewer received the entire deluxe package, of course; merely the five promo CDs in plain white inserts, all held together with a red elastic band that nicely replicated the colour scheme of the original record. The first two CDs feature said original album (no bonus tracks or outtakes) in two near-identical versions: the “original analogue master” on CD1, and the 1985 RCA re-master on CD2. The only difference, as far as I can tell - though I'm no audiophile - is that CD1 sounds slightly flat, while CD2 sounds slightly tinny. CD3 contains the single edits of five of the six album tracks, which are exactly the same, but hey- slightly shorter. And CDs 4 and 5 consist of a live recording of Bowie and band at the Nassau Coliseum on the 23rd of March 1976, trumpeted as “previously unreleased” but widely available on bootlegs for years; most famously, eleven of the fifteen tracks were packaged together with Bowie's toe-curling 'Young Americans' medley from the Cher Show (see youtube if you dare) on the Thin White Duke double album.

I could write a whole separate review of the live CDs, but suffice to say that we're a long way from the Spiders from Mars, and somewhere just east of jazz-funk hell; that the Dame goes through some half-dozen different comedy accents, often within the space of a single song; that they contain some of the most brilliant technical musicianship ever to be heard at a rock show, while also providing a dire warning of the dangers of putting three-chord garage rock numbers like 'Suffragette City' and 'Queen Bitch' – nice yodelling there, Dave - into the hands of over-achieving, coked-up musos; and that it features the most compellingly dreadful version of 'Waiting for the Man' ever executed, in which 'The Man' appears to be none other than that groovy cat Jesus Christ himself, my friends. You really should hear it; thankfully, it also comes packaged with the analogue master of the original album- that's the slightly flat one- in the much more reasonably priced 3-CD version. It's ridiculously, over-the-top brilliant and, yes, gloriously decadent.

Originally published in September 2010

https://medium.com/the-homesick-society/brian-eno-for-bibliophiles-9e35f93563fa

Brian Eno For Bibliophiles

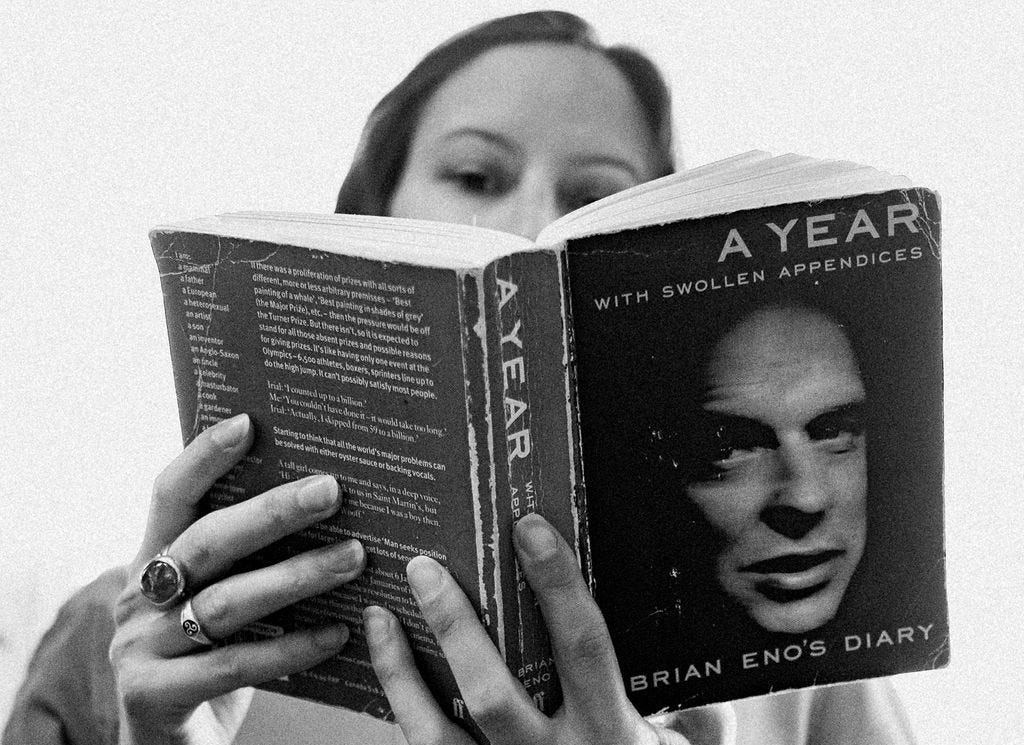

In which I surrender to a massive crush on Brian Eno, and strongly recommend you read his newly reissued diary.

It is October, 2005. I am a 20-year-old Alaskan, overseas for the first time, on a long-awaited study-abroad program at NUI Galway. The fact that I am really here feels a little extra surreal because it’s where my favorite novel, Juno & Juliet, is set. It’s written by some Irish fellow called Julian Gough, and it baffles me that any male could possibly write into being a female whose inner monologue so eerily matches my own. Twitter has not yet been invented, which means there’s no way to investigate him online, so I do it the old-fashioned way — I find him in the pub, and say hi. We strike up something that’s not just an easy-going friendship, but also not a romance — a strange fondness, you might call it.

For my birthday that February, Julian gives me a book: A Year With Swollen Appendices, by Brian Eno. At 21, I am vaguely aware of Brian Eno as that guy who looks the most mundane in footage of U2, and the most freaky in images of Roxy Music. I know a lot of music-obsessed dudes, like my brother, think highly of him, read entire essays he’s written on bells and things like that. Why one would read his daily diary entries from 1995, I have no idea. But this book clearly means a lot to Julian, and that he would think to get me a birthday present means a lot to me.

Julian and I each leave Ireland soon thereafter, and fall out of each other’s lives. It is not until we reconnect, eight years later, that we fall back into each other’s lives, so much so that we end up married. By this time, Julian has become a really wonderful writing teacher, and as his partner, I get to tag along to residencies at universities in Dublin, Limerick, and Singapore; it’s a bit like doing a series of MFA programs where you don’t pay any fees, and you get to sleep with your cute professor — a real win-win. One of the side effects of this writing-centered lifestyle is that, increasingly, the only music I can bear listening to is the sort that helps me hear myself think. And the bulk of such music, I am slowly discovering, is created by Brian Eno, either on his own or with others: Cluster, Harmonia, Harold Budd, Robert Fripp, Roger Eno, Karl Hyde, Daniel Lanois, U2…

One week, in spring 2017, Julian is away, teaching at a retreat in Scotland. The rightfully notorious Irish rain is hammering the windows, and my cat and I are bundled beside the radiator. I’m trying to use Julian’s absence to tackle something challenging, and decide to revisit a story I’ve been struggling with for ages. It’s inspired by one of my now-favorite albums, ‘Another Green World’. I have the idea to base one of the characters very loosely on Brian Eno, since it’s his music and lyrics I’m using as the parameters to build the story. Then I realize I can’t really base a fictional character on him when I don’t know anything about him. I at least need a sense of how he speaks, to help me with the dialogue. I go to YouTube.

A few videos in, I have been led to an interview from 1999. Eno would have been 51 that year (which is, coincidentally, the same age Julian is in 2017). Gone are the makeup, feathers, balding mullet, and garish shirts of his incarnations through the 70s and 80s. His head is entirely clean shaven, his clothes entirely black, and the studio he sits in is dim. His head hovers luminous in the gloom, like a cross between a Zen monk and a Cheshire Cat. Stripped of distraction, I notice for the first time that he has striking blue eyes. And that his mouth, which is always either articulating very thoughtful ideas or laughing, is actually quite sensual. He exudes a kind of warmth really. No, not just warmth…

Oh shit, Brian Eno is hot. Like, really hot. How did I never realize he was hot? Was he always hot? When did this happen?!

And just like that, a massive crush sparks into being. The only crush in all my years mated with Julian. Apparently, I have a type; significantly older, brilliant, funny men born in England, whose work began making an intimate impression on me as I went through puberty. It’s pretty niche. When the one I’m married to isn’t around to chat with, I put on interviews with the other. The amount of time I end up watching and listening to Eno as a result is, frankly, embarrassing. But I so enjoy his voice, and his ideas, and I do learn more than enough to base a character on him. Some of the things I learn are that he reads a lot, likes cats, drinks tea (Oh my gosh, we have so much in common). He cares a great deal about science, art, society, and the climate. He talks a lot about how humans have conflicting cravings for control and surrender. He also talks about trying to be a person who “lives at the extremes” of their passions and intellect at the same time, and how he tries to make music that combines both, and I realize this is the quality that makes his work so uniquely exciting. I have no idea what he is like in real life, but on camera he is unpretentious, hilarious, and compelling; the unrivaled champion of the thinking woman’s crumpet.

Unfortunately, his interviewers seem woefully oblivious to this. They’re almost always dudes, unaware of him as anything more than an oracular brain in a jacket, and look a little panicked when he tries to bring anything jokey or heartfelt or remotely sexual into the conversation. They seem to think their job is to ask about his definition of ’scenius’ for the twelve-millionth time, and move on. I find this prudish engagement deeply annoying. I am left with so much to wonder.

But I own this man’s diary, I realize. Why the hell have I never read it?

Yes, over a decade since Julian gifted it to me, the shameful truth is that I still haven’t read the bloody thing. This is partly because the decade has been so tumultuous, and so migratory, that most of my books have spent the time boxed away in garages and storage units. The other reason is to do with the fact that A Year With Swollen Appendices is not just a diary; nearly every entry has footnotes, and every few pages you are referred to one of the lengthy appendices at the back (hence the title). Altogether, it’s as wide and dense as a brick. Every couple of years or so, I would get it out, flip back and forth between the actual diary entries, the corresponding footnotes, the appendices, and make it to maybe February, before something would come up and I packed the thing away again. As a result, I’d read roughly one-tenth of the book about five times, but never the thing in its entirety. And now I am absolutely kicking myself.

Just as my crush is really taking off, Julian has been recommending Eno’s diary to his Limerick students. We are dividing the year between four countries, and living out of suitcases, so my copy is, yet again, in storage, in a concrete high-rise off Frank-Zappa-Strasse, in the bowels of East Berlin. Julian decides to just buy a new copy, and is shocked to discover the book is out of print, and that what rare used copies are to be found online cost well over €100. So we wait until our nomadic year ends, and we have found a new apartment in Berlin, before we recover our books, amongst which we find the now-coveted copy of the diary. Finally, after a thirteen year delay, I settle in, and read the fuck out of it.

After living with this man so much in my head, it is a pleasure, and a gift, to be allowed to spend time in his. Or at least, the version of him that existed in 1995. Fun facts about Eno that have never once come across in an interview jump out readily from his own writing. He cooks a lot, and has strong convictions about oyster sauce. He adores his daughters, and really engages when they play and create and talk with him. He has horrific sleep patterns. He likes flirting, and has a perpetual enthusiasm for women’s bottoms. His schedule is a relentless and varied combination of family life, studio work, charity projects, teaching, parties, events, installations. When he does find time for procrastination, he creates his own pornography in Photoshop (now where is that book, Faber?).

He does a great deal of travel, mainly for work. Trips to Belgium, Italy, Germany, Egypt, Bosnia, Austria, France, Monaco, Italy, New York, and the Netherlands, but mostly to Dublin, where he is recording the Passengers album with U2. In addition to very detailed and affectionate accounts of laying down vocals and partying with Bowie and Bono, there are recording sessions with Elvis Costello, James, and The Cranberries. Parties with the likes of Laurie Anderson, Gavin Friday, Jarvis Cocker, Björk. You pick up a fair amount of gossip. Eno’s frustration with arguments and disorganization in the studio. Which of his friends’ wives he fancies. There are also more somber entries. Family health scares. Periods of self-doubt and despair. And news from the war in Yugoslavia, which hangs over everything that year.

Somehow, alongside everything else he’s juggling, he manages to find the time and headspace for a lot of quite substantial reading matter, which he discusses in detail in long letters to his friends. In particular, his friend Stewart Brand, with whom he is in the process of helping set up The Long Now Foundation. Several of their letters are reproduced within the diary and in its appendices. The appendices are also packed with supremely thoughtful essays on culture, technology, art, and music, and are interspersed with smutty short stories.

Reading Eno’s diary gives me a lot to think about. And it gets me thinking about his body of work. (Of work, I said! Of work.) The sheer amount of time I’d spent listening to music he’d either composed, collaborated on, or produced. While I wrote. While I walked, ran, or drove down the road. While I puttered around the kitchen. While I danced. While I lay in bed, in both erotic and daydreaming states. No matter the decade or city — in London, Anchorage, and Berlin — he had been there. He had soundtracked virtually my entire life, and I was only now realizing it. Like how they say a frog won’t know it’s being boiled if you only turn the temperature up slowly, my life had slowly been Eno-ed and Eno-ed, to the point of saturation where I can’t avoid him if I try.

And I do try, occasionally. In the kitchen, I turn on the BBC’s Woman’s Hour thinking, surely, that will be an Eno-free zone. But no, the program that day opens with a startlingly deep voice: Eno reading out the essay he’s written for the BBC ‘Rethink’ series. I go to the living room — Julian has Eno’s diary out, trying to find the entries where he talks about the philosopher Richard Rorty. I take my son out for a walk. In a box of giveaway items on the street, I spot a Robert Wyatt CD, and knowing Julian likes Wyatt, I grab it. Back home, Julian starts reading out the liner notes — Eno is on three of the tracks.

Mother of fuck. Okay Brian, you win. I surrender.

After finally reading Eno’s diary in full last year, I decide I will try keeping my own page-a-day diary for 2020. I buy a nice red Moleskin diary, its brightness a vote of confidence for how fun the year will be. In stark contrast to these expectations, and to Eno’s diary, mine has ended up mainly a record of how many times my son has broken my sleep to breastfeed in the night, and how shattered I feel that day as a result. The pandemic has robbed the year of so many things I had looked forward to, left little else to make note of besides a sprinkling of dreams, first words, failed plans, and deaths. It has not been the year I had hoped it would be, and in that I know I am in good, global company.

One of the few good surprises of 2020 is that, 25 years after it was written, A Year With Swollen Appendices is finally coming back in print. Faber have created a new hardback edition, with ribbon place-markers and the whole shebang for the occasion, which is 19 November on this side of the Atlantic, though not til February 9 for the US. It looks beautiful. I suspect we’ve got a long winter ahead of us, and I highly recommend this dense, rich tome to anyone wondering how on earth they’re going to sustain their brain through it. I mean, you could do worse than escaping into the world of a sexy genius who travels the world making art and dining with legends. At the same time, if you’re looking to make something with this time, the essays on culture and creativity will prompt new ways of thinking about your craft. And as it turns out, you can listen to his new album of Film Music (out this Friday the 13th) while you read and work. Both book and album will be in heavy rotation in our household, and I’m sure yours would benefit from them, too. The book is unlikely to cast as long a shadow over so much of your life — or embed itself so weirdly into your marriage — as it has for me. But you never know where this reading business will lead you…

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2103.08 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2075 days ago