Today is SHARE day, so these two posts -- one from 2021 and one from 2022. And another one via SLASHDOT from the BAFFLER.

And so I offer this today as a share because many people have the kinds of jobs that can be done at home and maybe, from now on, should be.

Thanks for tuning in as always.

ENJOY.

As vaccinations and relaxed health guidelines make returning to the office a reality for more companies, there seems to be a disconnect between managers and their workers over remote work.

A good example of this is a recent op-ed written by the CEO of a Washington, D.C., magazine that suggested workers could lose benefits like health care if they insist on continuing to work remotely as the COVID-19 pandemic recedes. The staff reacted by refusing to publish for a day.

While the CEO later apologized, she isn’t alone in appearing to bungle the transition back to the office after over a year in which tens of millions of employees were forced to work from home. A recent survey of full-time corporate or government employees found that two-thirds say their employers either have not communicated a post-pandemic office strategy or have only vaguely done so.

As workforce scholars, we are interested in teasing out how workers are dealing with this situation. Our recent research found that this failure to communicate clearly is hurting morale, culture and retention.

Workers relocating

We first began investigating workers’ pandemic experiences in July 2020 as shelter-in-place orders shuttered offices and remote work was widespread. At the time, we wanted to know how workers were using their newfound freedom to potentially work virtually from anywhere.

We analyzed a dataset that a business and technology newsletter attained from surveying its 585,000 active readers. It asked them whether they planned to relocate during the next six months and to share their story about why and where from and to.

After a review, we had just under 3,000 responses, including 1,361 people who were planning to relocate or had recently done so. We systematically coded these responses to understand their motives and, based on distances moved, the degree of ongoing remote-work policy they would likely need.

We found that a segment of these employees would require a full remote-work arrangement based on the distance moved from their office, and another portion would face a longer commute. Woven throughout this was the explicit or implicit expectation of some degree of ongoing remote work among many of the workers who moved during the pandemic.

In other words, many of these workers were moving on the assumption – or promise – that they’d be able to keep working remotely at least some of the time after the pandemic ended. Or they seemed willing to quit if their employer didn’t oblige.

We wanted to see how these expectations were being met as the pandemic started to wind down in March 2021. So we searched online communities in Reddit to see what workers were saying. One forum proved particularly useful. A member asked, “Has your employer made remote work permanent yet or is it still in the air?” and went on to share his own experience. This post generated 101 responses with a good amount of detail on what their respective individual companies were doing.

While this qualitative data is only a small sample that is not necessarily representative of the U.S. population at large, these posts allowed us to delve into a richer understanding of how workers feel, which a simple stat can’t provide.

We found a disconnect between workers and management that starts with but goes beyond the issue of the remote-work policy itself. Broadly speaking, we found three recurring themes in these anonymous posts.

1. Broken remote-work promises

Others have also found that people are taking advantage of pandemic-related remote work to relocate to a city at a distance large enough that it would require partial or full-time remote work after people return to the office.

A recent survey by consulting firm PwC found that almost a quarter of workers were considering or planning to move more than 50 miles from one of their employer’s main offices. The survey also found 12% have already made such a move during the pandemic without getting a new job.

Our early findings suggested some workers would quit their current job rather than give up their new location if required by their employer, and we saw this actually start to occur in March.

One worker planned a move from Phoenix to Tulsa with her fiancé to get a bigger place with cheaper rent after her company went remote. She later had to leave her job for the move, even though “they told me they would allow me to work from home, then said never mind about it.”

Another worker indicated the promise to work remotely was only implicit, but he still had his hopes up when leaders “gassed us up for months saying we’d likely be able to keep working from home and come in occasionally” and then changed their minds and demanded employees return to the office once vaccinated.

2. Confused remote-work policies

Another constant refrain we read in the worker comments was disappointment in their company’s remote-work policy – or lack thereof.

Whether workers said they were staying remote for now, returning to the office or still unsure, we found that nearly a quarter of the people in our sample said their leaders were not giving them meaningful explanations of what was driving the policy. Even worse, the explanations sometimes felt confusing or insulting.

One worker complained that the manager “wanted butts in seats because we couldn’t be trusted to [work from home] even though we’d been doing it since last March,” adding: “I’m giving my notice on Monday.”

Another, whose company issued a two-week timeline for all to return to the office, griped: “Our leadership felt people weren’t as productive at home. While as a company we’ve hit most of our goals for the year. … Makes no sense.”

After a long period of office shutterings, it stands to reason workers would need time to readjust to office life, a point expressed in recent survey results. Employers that quickly flip the switch in calling workers back and do so with poor clarifying rationale risk appearing tone-deaf.

It suggests a lack of trust in productivity at a time when many workers report putting in more effort than ever and being strained by the increased digital intensity of their job – that is, the growing number of online meetings and chats.

And even when companies said they wouldn’t require a return to the office, workers still faulted them for their motives, which many employees described as financially motivated.

“We are going hybrid,” one worker wrote. “I personally don’t think the company is doing it for us. … I think they realized how efficient and how much money they are saving.”

Only a small minority of workers in our sample said their company asked for input on what employees actually want from a future remote work policy. Given that leaders are rightly concerned about company culture, we believe they are missing a key opportunity to engage with workers on the issue and show their policy rationales aren’t only about dollars and cents.

3. Corporate culture ‘BS’

Management gurus such as Peter Drucker and other scholars have found that corporate culture is very important to binding together workers in an organization, especially in times of stress.

A company’s culture is essentially its values and beliefs shared among its members. That’s harder to foster when everyone is working remotely.

That’s likely why corporate human resource executives rank maintaining organizational culture as their top workforce priority for 2021.

But many of the forum posts we reviewed suggested that employer efforts to do that during the pandemic by orchestrating team outings and other get-togethers were actually pushing workers away, and that this type of “culture building” was not welcome.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

One worker’s company “had everyone come into the office for an outdoor luncheon a week ago,” according to a post, adding: “Idiots.”

Surveys have found that what workers want most from management, on the issue of corporate culture, are more remote-work resources, updated policies on flexibility and more communication from leadership.

As another worker put it, “I can tell you, most people really don’t give 2 flips about ‘company culture’ and think it’s BS.”

The great enforced global experiment in working from home is coming to an end, as vaccines, the Omicron variant and new therapeutic drugs bring the COVID-19 crisis under control.

But a voluntary experiment has begun, as organisations navigate the new landscape of hybrid work, combining the best elements of remote work with time in the office.

Yes, there is some push for a “return to normal” and getting workers back into offices. But ideas such as food vouchers and parking discounts are mostly being proposed by city councils and CBD businesses keen to get their old customers back.

A wide range of surveys over the past 18 months show most employees and increasingly employers have no desire to return to commuting five days a week.

The seismic shift in employer attitudes is signalled by Google, long a fierce opponent of working from home.

Last week the company told employees they must return to the office from early April – but only for three days a week.

That’s still way more than tech companies such as Australia’s Atlassian, which expects workers to come into the office just four days a year, but it is a far cry from its pre-pandemic resistance to remote work.

Hybrid work is here to stay. Employers will either embrace the change or find themselves being left behind.

Gains in productivity

Google began – under pressure – to soften its opposition to remote work in 2020. In December of that year chief executive Sundar Pichai told employees:

We are testing a hypothesis that a flexible work model will lead to greater productivity, collaboration, and well-being.

Its chief concern has been protecting the social capital that springs from physical proximity – and also perhaps with keeping employers under surveillance.

But longstanding (and widespread) management concerns that employees working from home would lower productivity have proven unfounded.

Even before the pandemic there was good research showing no productivity penalty from remote working – the opposite, in fact.

For example, a 2014 randomised trial involving about 250 Shanghai call centre workers found working from home associated with 13% more productivity. This comprised a 9% gain from working more minutes per shift – due perhaps to fewer interruptions – and a 4% gain from making more calls per minute – attributed to a quieter, more comfortable working environment.

Research in the past two years supports these findings.

Harvard Business School professor Raj Choudury and colleagues published research in October 2020 that found allowing employees to work wherever they like led to a 4.4% increase in output.

In April 2021, Stanford University economist Nick Bloom and colleagues calculated a the shift to remote working resulted in a 5% productivity boost. Though their working paper, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, was not peer reviewed, it was based on surveying 30,000 American workers, which is a decent sample size.

Our relationship with work has changed

There are good reasons most of us don’t want to go back to the old normal. It just wasn’t that great.

While working from home can brings challenges of other kinds, not least the ability to switch off and stop working when work is done, working in an office can increase stress, lower mood and reduce productivity.

My own research has measured the effects of typical open-plan office noises, finding a 25% increase in negative mood even after a short exposure time.

Then there’s the time spent commuting. Not having to go into the office every day frees up hours of time to do other things. Particularly in winter it’s nice to not have to leave and arrive home in the dark.

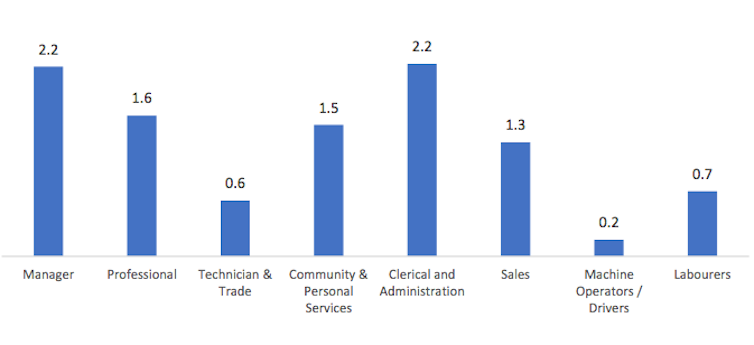

Preferred number of days working at home, by occupation

|

| Results from a survey of Australian workplaces during 2020 lockdowns. Institute of Transport and Logistic Studies, University of Sydney, CC BY |

Changed expectations of work

The importance of these things should not be underestimated.

In a June 2021 study by McKinsey of 245 employees who had returned to the office, one-third said they felt their mental health had been harmed.

The experience of the pandemic has lowered our tolerance for this old world of work.

Nothing exemplifies this better than the growth of the “lie-flat” trend, which began in China and is now a global phenomenon. Increasing numbers of people are rejecting the idea of pursuing a career at all costs.

They don’t want to spend their life being a cog in the wheel of capitalism and are choosing to work less – even not at all.

No one size fits all

Rather than a bastion of meaning and fulfilment, the structures around how we have conducted work has for many people meant an existence of quiet desperation. The pandemic has brought an unforeseen opportunity to change this narrative and rethink both the way we work and the role of work in our lives

For some, no job is better than a bad job. The rest of us will settle for the flexibility we’ve had over the past two years.

No one size fits all. The downsides of working from home include missing coworkers and losing the benefits of serendipitous conversations. The nuances of how much time we need to spend together in the office for outcomes like creativity, belonging, learning and relationship building varies between individuals, teams and job types.

But what is certain is we don’t need to be together five days a week to make these things happen. With a shrinking workforce and an increasing war for talent, employers who don’t provide flexibility will be the losers.

And then the essay turns to Jonathan Malesic's new book The End of Burnout:He casts a critical eye on burnout discourse, in which the term is used loosely and self-flatteringly. Journalistic treatments of burnout — such as Anne Helen Petersen's widely read 2019 essay — tend to emphasize the heroic exertions of the burned-out worker, who presses on and gets her work done, no matter what. Such accounts have significantly raised burnout's prestige, Malesic argues, by aligning the disorder with "the American ideal of constant work." But they give, at best, a partial view of what burnout is. The psychologist Christina Maslach, a foundational figure in burnout research — the Maslach Burnout Inventory is the standard burnout assessment — sees burnout as having three components: exhaustion; cynicism or depersonalization (detectable in doctors, for example, who see their patients as "problems" to be solved, rather than people to be treated); and a sense of ineffectiveness or futility.... Accounts of the desperate worker as labor-hero ignore the important fact that burnout impairs your ability to do your job. A "precise diagnostic checklist" for burnout, Malesic writes, would curtail loose claims of fashionable exhaustion, while helping people who suffer from burnout seek medical treatment.

Malesic, however, is interested in more than tracing burnout's clinical history. A scholar of religion, he diagnoses burnout as an ailment of the soul. It arises, he contends, from a gap between our ideals about work and our reality of work. Americans have powerful fantasies about what work can provide: happiness, esteem, identity, community. The reality is much shoddier. Across many sectors of the economy, labor conditions have only worsened since the 1970s. As our economy grows steadily more unequal and unforgiving, many of us have doubled down on our fantasies, hoping that in ceaseless toil, we will find whatever it is we are looking for, become whoever we yearn to become. This, Malesic says, is a false promise.... [The book] is an attack on the cruel idea that work confers dignity and therefore that people who don't work — the old, the disabled — lack value. On the contrary, dignity is intrinsic to all human beings, and in designing a work regime rigged for the profit of the few and the exhaustion of the many, we have failed to honor one another's humanity.... William Morris, in his famous essay "Useful Work Versus Useless Toil," dreamed of a political transformation in which all work would be made pleasurable. Malesic thinks, instead, that work should not be the center of our lives at all....

Burnout is an indicator that something has gone wrong in the way we organize our work. But as a concept it remains lodged in an old paradigm — a work ethic that was already dubious in America's industrial period, and now, in a period of extreme inequality and increasing precarity across once-stable professions, is even harder to credit.... The top 1 percent of the income distribution is composed largely of executives, financiers, consultants, lawyers, and specialist doctors who report extremely long work hours, sometimes more than seventy a week....

But the strange work ethic the rich have devised seems highly relevant for our understanding of burnout as a cultural phenomenon, especially as it spreads beyond its traditional victims — doctors, nurses, teachers, social workers, anti-poverty lawyers — and courses through the ranks of knowledge workers more generally."

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2203.29 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2461 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment