Today's share.

I am not going to get in the way of this reporting with a lot of rhetoric.

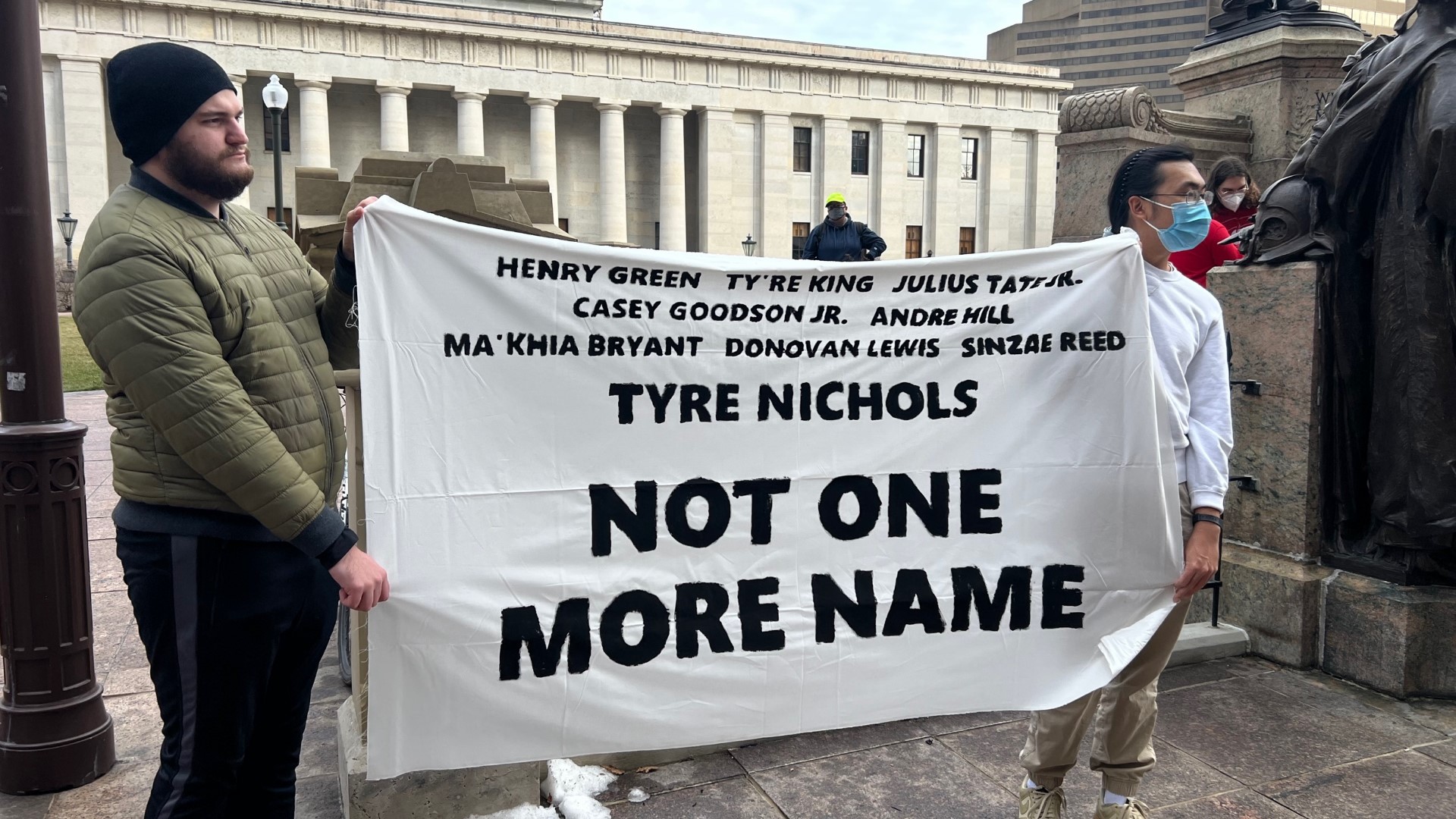

We have been through this tragedy before, many times.

Say his name.

|

| https://stand.org/tennessee/blog/justice-for-tyre-nichols/ |

‘Shortness of breath’: How police first describedwhat happened to Tyre Nichols

By Justine McDaniel and Dan Rosenzweig-Ziff January 28, 2023 at 10:15 p.m. EST

Brutal video footage released Friday, an hour’s worth of clips from body-worn and mounted cameras showing police pepper-spraying, punching and kicking Nichols, underscores the disparity between what police first reported and what actually happened.

Across the country, police sometimes use passive language that can paint a very different picture from what cameras later show. Initial news releases are often based on police officers’ self-reporting, and were it not for the ubiquity of cameras in modern times, the discrepancies between those filings and the reality of a police interaction may never come to light.

“If you read that report, you would not think that Tyre is dead because of excessive force. It’s written in a way to be positive toward those law enforcement agents,” Van Turner, the president of the Memphis NAACP, said of the initial news release. “The report is disingenuous. It’s fabricated.”

Rather than simply complaining of shortness of breath, Nichols, the video showed, could barely sit up after the beating. Officers propped him up against a police car, where he repeatedly slumped over. He can be heard groaning but is not heard forming any words. He twists and writhes against the police car, at times falling over on his side, as he waits 22 minutes for an ambulance.

Nichols died three days later. His case sparked national outrage and investigations by the FBI and Justice Department.

It echoes other cases, including that of George Floyd, in which initial police reports painted a sanitized picture of a violent or fatal interaction. At the same time, the police investigation that came after that first Memphis report moved so swiftly that experts have pointed to it as an unusually capable response to officer brutality.

Memphis Police Chief Cerelyn Davis herself questioned that first report, later telling CNN she received an incident report at 4 a.m., hours after the beatings, thought it was a “strange summary of what occurred on a traffic stop,” and went to the office to investigate.

The Memphis Police Department did not respond to questions from The Washington Post on Saturday.

“In this particular case, it seems very different from very active coverups that I’ve seen in other instances,” said Rajiv Sethi, a professor at Barnard College who studies police use of lethal force. “The initial statement was very quickly reversed.”

Still, the first narrative often sticks, said Lauren Bonds, executive director of the National Police Accountability Project. The initial framing of an inaccurate narrative by police is a tactic often seen after brutality by officers, she said; though parts of Memphis’s response were fast and transparent, she said she would not look to it “as a model.”

“Even though we’ve seen the videos now, if you’re going through [a certain] segment of Twitter, you’re still seeing some people saying this and this were true or he shouldn’t have ran,” Bonds said. “There’s things that came out of that initial presentation of the facts that are going to stick with people.”

Before body cameras became widespread, the police’s word was often unchallenged by the media or otherwise, said Dan Kennedy, a longtime media observer and journalism professor at Northeastern University.

While videos can show what police do not write in incident reports, experts also say officers could be starting to use body cameras to influence narratives. Some believed they saw that in the Nichols videos.

In the first altercation shown in the videos, multiple officers shout at Nichols to lie down, though he is already pinned to the ground from shoulders to feet. “I am,” he shouts back, desperate. During the second video, officers tell Nichols to give them his hands when an officer is already holding him by the wrist; then the body camera points away. Officers also say on film that Nichols reached for their guns and is high, neither of which the videos show, though their first traffic stop was not included in the videos because it wasn’t filmed.

Officer tells Nichols to give them his hands when an officer is already holding him by the wrist. (Video: Memphis Police Dept.)

“It appeared to me that one or more officers were providing a false narrative to accompany the video recording in real time. They were saying things like, ‘Give me your hands’ when they already had his hands,” said Philip M. Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University who researches police crime.

Turner, of the Memphis NAACP, also said he interpreted what the officers said in the videos as an attempt to cover up what had happened moments before.

“You’re seeing this more and more. They’re almost acting like the cameras didn’t catch what happens,” Turner said. “For this guy to say Tyre reached for his gun, but we didn’t see that, it is dumbfounding.”

However, Sethi said police officers take into account the fact that they’re being recorded, but in this case, they may not have been thinking of the Nichols interaction as anything out of the ordinary and thus would not have been speaking for the camera’s benefit.

“I don’t think those officers expected,” he said, “that Nichols would not survive.”

In other cases, incident reports often obscured abuses. Floyd “appeared to be suffering medical distress,” read the Minneapolis police statement about his death. Louisville police listed Breonna Taylor’s injuries as “none,” though six shots struck her, including one bullet near her heart, an autopsy later showed. During an “altercation” in Grand Rapids, Mich., “the officer fired his weapon” at Patrick Lyoya, “striking the individual who died as a result of his injuries.” But it did not report the details: an officer tackling Lyoya to the ground and later firing a single round into the back of his head, according to video that was later released.

Police statements are often written by public information officers using reports written by the officers involved in the incident, Stinson said.

In the case of Floyd, the public information officer who wrote the report had not seen the video of Derek Chauvin’s knee choking Floyd beforehand. And in Nichols’s case, the first public statement came early the following morning, just hours after the police chief had been notified of the incident at 4 a.m.

Though this case joins that list, authorities’ later response was “commendable,” Turner said. After investigations, five officers were fired and then charged with second-degree murder before the video footage was released, three weeks after the incident.

“I’d rather have the police being transparent, not prolonging the investigation and bracing the public for a brutal video,” Turner said, comparing the response with that in other police killings, “than what’s happened in the past.”

The death of Tyre Nichols

The latest: One of the former Memphis police officers charged with murder texted a photo of bloodied Tyre Nichols to colleagues, according to new state records.

What has Memphis police footage revealed?: The race of the five officers charged in the Nichols killing has sparked a complex dialogue on institutional racism in policing. Some of the most haunting videos came from SkyCop cameras.

Who was Tyre Nichols?: The 29-year-old father was pepper-sprayed, punched and kicked by Memphis cops after a January traffic stop. He was pronounced dead at a hospital three days after the officers arrested him. Four of the cops were previously disciplined. At Tyre Nichols’ funeral service, his family said they are focused on getting justice.

What is the Scorpion unit?: After the fallout from the brutal beating, Memphis police shut down the Scorpion unit. Memphis police chief Cerelyn Davis currently leads the department.

Black Memphis police spark dialogue on systemicracism in the U.S.

By Robert Klemko, Silvia Foster-Frau, and Emily Davies

Updated January 29, 2023 at 9:04 p.m. EST|Published January 29, 2023 at 7:15 p.m. EST

The race of the five officers charged in the Nichols killing has prompted a complex grappling among Black activists and advocates for police reform about the pervasiveness of institutional racism in policing. Nichols died three days after he was pulled out of his car Jan. 7, kicked, punched and struck with a baton on a quiet neighborhood street by Black officers, whose aggressive assault was captured on body-camera videos released Friday.

The widely viewed videos of the Nichols beating provided fodder for right-wing media ecosystems that routinely blame Black America’s maladies on Black America, and spawned nuanced conversations among Black activists about how systemic racism can manifest in the actions of non-White people.

The Memphis Police Department, which has nearly 2,000 officers, is 58 percent Black, the result of a decades-long effort to field a police force that resembles the city’s 64 percent Black population. Unlike in several recent high-profile police brutality cases, Memphis Police Chief Cerelyn Davis, who is Black, and other officials acted swiftly in firing, arresting and charging the Memphis officers in advance of the release of video footage.

Though some studies have shown that police officers of color use force less frequently against Black civilians than their White counterparts, analysts say the improvement is marginal.

“Diversifying law enforcement is certainly not going to solve this problem,” said Samuel Sinyangwe, president of Mapping Police Violence.

He pointed to many factors in the policing system that lead to a disproportionate response against people of color: directives to work in neighborhoods where more people of color live and a system that relies on the discretion of the officer to enforce things like traffic stops, opening the door for internal biases to play a role.

Conversations on Fox News over the weekend were less academic.

“Tucker Carlson Tonight” guest Jason Whitlock, a conservative sports culture blogger who is Black, blamed “young Black men and their inability to treat each other in a humane way,” as muted footage of the Memphis officers beating Nichols played side-by-side.

“It looked like gang violence to me. It looked like what young Black men do when they’re supervised by a single, Black woman,” Whitlock said, referring to Davis, the Memphis police chief, who is married.

Focus on the individual officers in the aftermath of police killing and not the institution the officer belongs to perpetuates the belief that policing’s problems are the result of a few bad apples — a narrative embraced by police, said Jeanelle Austin, who runs the George Floyd Global Memorial in Minnesota.

“This is what I fear: What’s going to happen in Memphis is what happened to Minneapolis — is that when Derek Chauvin and the other [three] officers were charged, the narrative turned from an issue of the police department to an individual issue,” Austin said. “That was a PR strategy.”

“What we’ve been screaming from our lungs for years is that the system and the culture of policing trains people’s minds regardless of the color of their skin to behave a certain way,” she said.

Systemic racism can be more difficult for the general public to grasp than explicitly visible White-on-Black crimes, said Craig Futterman, a clinical professor of law at the University of Chicago Law School who studies policing and civil rights.

“We’d like to think in the binary — the good guys and the bad guys,” he said. “It’s far easier to consume the story in an uncomplicated way seeing a White officer shoot 14 shots at a young Black boy laying on the ground,” he added, referencing the 2014 murder of Laquan McDonald.

From the protests in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014 through those in 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, activists have long sought to reform policing. But the lack of centralization between local, state and federal police entities, along with failures in congressional action, has not resulted in widespread changes.

More than two weeks after Nichols was killed after being pulled over for what police said was reckless driving, Ayanna Robinson drove 6 1/2 hours from Indianapolis to Memphis to join demonstrations she thought would include thousands of protesters angered by his recorded beating by officers. She arrived to find dozens, not thousands, of protesters and they seemed calm.

Robinson, 28, a manager at a Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant, said the turnout was nothing like what she saw in Memphis after Floyd, a Black man, was murdered in Minneapolis police custody in May 2020. In a way, the city seemed too peaceful after the Nichols killing, she said.

“In order to get a reaction, there has to be a reaction, and right now there’s no type of action,” she said, looking around a park where 100 protesters gathered Friday evening.

Robinson said one of the major reasons she thought many people seemed more subdued in response to the Nichols death was that the five officers charged in beating him are Black. If the officers had been White, “All hell would have broken loose. The city would have been in war.”

Nikki Owens felt a similar frustration in the aftermath of the death of her cousin, William Green, who was shot to death while handcuffed by a Black officer in Prince George’s County, Md., in January 2020.

“In America we’re taught that racism is black and white,” said Owens, who now works with the Maryland Coalition for Justice and Police Accountability. “And we are not taught about institutional or systemic racism, even though we see it everywhere. We are taught that if a Black person kills another Black person, it can’t be racist. It’s ‘Black-on-Black crime.’”

Owens said that attitude contributed to her struggles to inspire activism among area residents and in getting national and local media coverage of her cousin’s killing.

“There wasn’t the outrage,” she said. “Even when George Floyd passed away, nobody reached out to us.”

Owens said she felt as if the world viewed her cousin’s death as somehow different than other police killings. The officer’s criminal trial begins this year.

“When I was out in the community and I would talk to people, I could see their reaction when I told them the officer was Black,” she said. “And some people would ask what color the officer was, which is another indication of that lack of understanding.”

Some protesters said that while the racism isn’t explicit, Nichols’s death could be a moment for the nation to understand the way pervasive, institutional racism functions, and how it can compromise individuals.

Bakari Sellers, a former South Carolina state legislator, civil rights attorney and CNN contributor, said the Nichols beating made him recall the Black Minneapolis police officer, J. Alexander Kueng, who knelt on Floyd’s back as Derek Chauvin suffocated him.

“He talked about how he thought he could make a difference in policing,” Sellers said of Kueng. “And then like three days after his hiring, he’s there watching George Floyd being brutalized and doing nothing about it.

“For many Black folks, the race of a cop is cop.”

Jason Sole, a community organizer in Minneapolis and former head of the local NAACP, said he’s never felt a sense of relief when encountering Black officers.

“I never had that feeling of ‘Oh great, it’s a Black cop, yay.’ No. I was born in ’78 and I never had that feeling, not once,” Sole said. “All your skinfolk ain’t kinfolk.”

Regardless of color, Sole said, “we need people who are loving, people who are showing we care, people who understand that grace has to be shown to everybody.”

Foster-Frau reported from Washington.

The death of Tyre Nichols

The latest: One of the former Memphis police officers charged with murder texted a photo of bloodied Tyre Nichols to colleagues, according to new state records.

What has Memphis police footage revealed?: The race of the five officers charged in the Nichols killing has sparked a complex dialogue on institutional racism in policing. Some of the most haunting videos came from SkyCop cameras.

Who was Tyre Nichols?: The 29-year-old father was pepper-sprayed, punched and kicked by Memphis cops after a January traffic stop. He was pronounced dead at a hospital three days after the officers arrested him. Four of the cops were previously disciplined. At Tyre Nichols’ funeral service, his family said they are focused on getting justice.

What is the Scorpion unit?: After the fallout from the brutal beating, Memphis police shut down the Scorpion unit. Memphis police chief Cerelyn Davis currently leads the department.

Police Charged With Killing Tyre Nichols Allegedly Beat Another Man Days Before

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2302.10 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2779 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment