I subscribed to the New Yorker to get this article on Critical Race Theory:

Like many posts that I will be making in the next few weeks, this one has been in the works for some time.

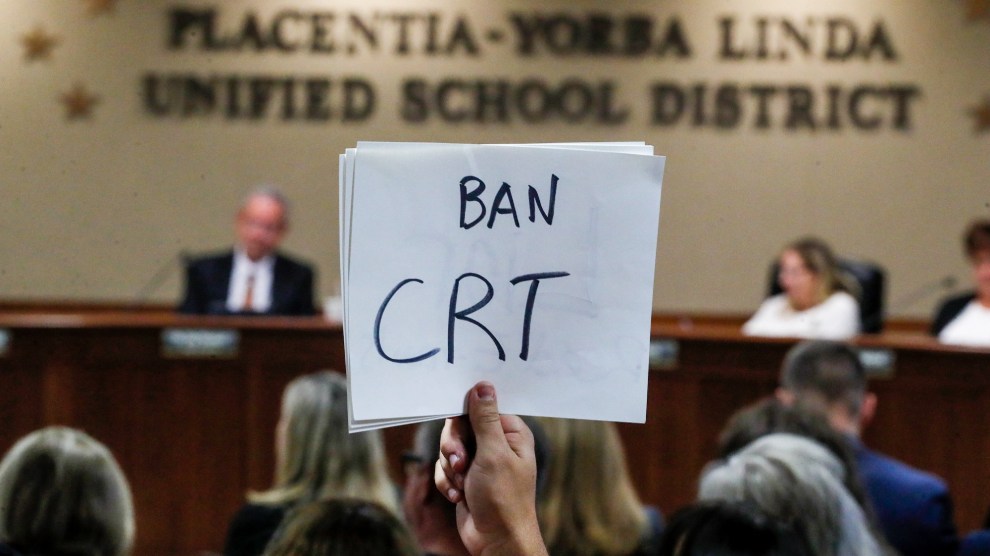

The joke going around is that most of the people who oppose Critical Race Theory don't know what it is and can't define it.

Or if they think they can define it, they're wrong.

I like this definition: CRT definition from 1619 article from the Washington Post 2302.02

Specifically, they are there to talk about John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, who was Virginia’s colonial governor during the American Revolution. In 1775, Dunmore issued a proclamation that, among other things, declared that any enslaved person who fought on behalf of Britain against the colonists would be granted their freedom — a proclamation that “infuriated White Southerners,” Holton says.The idea that some colonists chose to fight Britain in the American Revolution in part or solely to defend and retain the practice of slavery rankled many "patriots" in their beliefs about the freedom-fighting near holy nature of the founding fathers.

This controversy over the motivations of the freedom-fighting colonists represents the conflict over CRT perpetuated by many conservatives and proliferated by a very powerful propaganda machine: Fox "News."

The project, and the backlash, entailed more than a claim about the motives of colonists and a dispute over whether that claim should have come with caveats. It became a controversy about whether slavery or freedom should be more fundamental to the country’s self-image, in which historical correctness tangled with what’s politically acceptable and personally comforting.

“So much of the response,” Hannah-Jones said, “was people saying, ‘It can’t possibly be true,’ or ‘I certainly would have heard this before,’ ‘It unsettles everything I’ve been taught to believe,’ ‘I’ve never heard of this, so it must be a lie.’”

|

| https://www.abc10.com/article/news/nation-world/finnegan-maxwell-toddlers-hug-anti-racism-campaign/507-c7d1c464-b68a-465e-b982-bb9d99b052b6 |

Pennsylvania's anti-CRT bill, for instance, would prohibit university professors from teaching any "racist or sexist concept" or bringing an outside speaker to campus who does the same. Remember when conservatives were outraged about the disinvitation campaigns waged against campus speakers like Ben Shapiro and Milo Yiannopoulos? Well, this bill would make disinvitation the law of the land. University bureaucrats would have to scroll through prospective speakers' Twitter feeds, on the hunt for statements that could be read as racist or sexist. (This would obviously not benefit socially conservative speakers, many of whom do, after all, believe that there are differences between men and women and different roles for them in society.)

At the same time, anti-CRT folks on the right are correct that there are a whole host of progressive writers, teachers, and activists who were clearly inspired by critical race theory—a field that does in fact include fairly radical ideas, some of which run contrary to the colorblind liberalism of previous racial equality advocacy. Whether or not these people would admit to being adherents of CRT is almost beside the point.

|

| https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/critical-race-theory-ban-states |

Included in this mix are two of the least persuasive anti-racism writers: White Fragility author Robin DiAngelo and How to Be Antiracist author Ibram X. Kendi, who are routinely paid thousands of dollars to give short presentations to corporate employees, school administrators, and teachers. Both take wildly flawed approaches; DiAngelo treats racism as a kind of incurable infection, or original sin—John McWhorter accurately accused her of promoting the cultish notion that "you will never succeed in the 'work' she demands of you…it is lifelong, and you will die a racist just as you will die a sinner."

Kendi's big idea is to create a U.S. Department of Antiracism. "The DOA would be responsible for preclearing all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won't yield racial inequity, monitor those policies, investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces, and monitor public officials for expressions of racist ideas," he wrote. This proposal would necessitate the creation of a vast surveillance state and render the First Amendment moot.

The best solution is twofold. First, foes of critical race theory should spend their time more productively by working to ban racial discrimination in schools. Tinkering with the curriculum is usually a local issue, but states can prohibit race-based hiring and admissions systems. Bar elite public high schools from requiring white and Asian students to score higher on entrance exams, and from segregating students by race. David French is also correct that civil rights law already provides a potential avenue for students to sue school districts that have fostered a racially hostile and discriminatory climate. If the thinking behind "aspects of white supremacy culture" is put into practice in schools, those schools can be sued.

Second, Reason's J.D. Tuccille is completely correct that "the critical race theory debate wouldn't matter if we had more school choice." Families deserve more control over their children's education, and the best way to give it to them is to let students attend whatever school best fits their needs. If parents are concerned that a district is regularly training its teachers to espouse a DiAngelo-esque worldview, the easiest solution is to empower the kids to go elsewhere.

“The critical race theory (CRT) movement,” explain legal scholars Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, “is a collection of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power.” Its most direct academic origins can be found in the work of the late Harvard law professor Derrick Bell, who rigorously challenged mainstream liberal narratives of steady racial progress, illustrating how landmark legislation — the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 — failed to deliver liberty and justice for Black Americans.

|

| https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/critical-race-theory-law-systemic-racism/2021/07/02/6abe7590-d9f5-11eb-8fb8-aea56b785b00_story.html |

Attacks on critical race theory are everywhere these days: Its detractors claim that the academic movement is “planting hatred of America in the minds of the next generation” and “advocating the abhorrent viewpoint that Blacks should forever be regarded as helpless victims,” and say that it might even qualify as “child abuse.”

Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) held up the Senate confirmation of one of President Biden’s nominees “because of her history promoting radical critical race theorists,” Hawley’s spokeswoman said. Delivering a speech in June pretty clearly aimed at bolstering his political prospects, former vice president Mike Pence said that “critical race theory teaches children as young as kindergarten to be ashamed of their skin color.”

Wrong.

Indeed wrong.

But this is the problem. Politicians, radio broadcasters and podcasters, Fox "News" commentators all parrot dangerous, destructive, and wildly inaccurate if not outright offensive ideas about CRT. And the more they repeat this disinformation (if not outright MALINFORMATION), the more people parrot it onward and warp it farther, hence the "child abuse" accusation.

And then this part:

The concept is certainly left-leaning, and it shakes up the traditional story of America as the unalloyed land of the free. But its central contention isn’t particularly radical or difficult to grasp. Far from preaching anti-Whiteness or Black victimhood, or rejecting individual rights, critical race theorists seek to explain how our laws and institutions — colorblind in theory — continue to circumscribe the rights of racial minorities. In the post-Jim Crow, post-Brown v. Board era, they ask, why and how do race and racism continue to play a constitutive role in America?

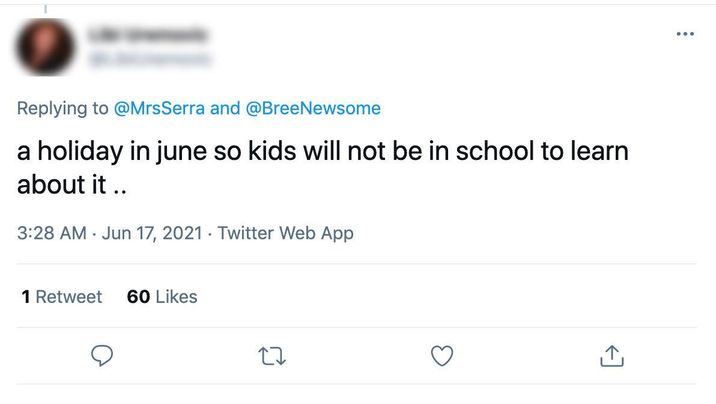

But go on Twitter and review hash tags. #BanCRT was trending and peaked in 2021 though it still rears its ugly head today, but a review will reveal other hash tags and terms and slogans of the Right-side propaganda machine, such as Regressive Left, Woke Mind Virus, Liberalism is a Mental Disorder, Liberal Corruption, Clown World, and more. It's a toxic waste land of vicious hyperbole, insult, and often outright threats of violence. It's such an unleashing of hate and outrage that it's difficult to understand how those perpetuating it do not see how it's clearly projection. In response, those on the Left are just trying to play defense because their media are not propaganda, fomenting them into a frenzy of spit-spewing vitriol.

What developed as a framework for interrogating racial dynamics in American legal institutions influenced academics in neighboring disciplines, notably including sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s conceptualization of “color-blind racism,” philosopher Charles W. Mills’s notion of a “racial contract” and education scholar Gloria Ladson-Billings’s analysis of the racial achievement gap. These works helped reinforce the insight that our country’s severe racial inequities are deeply embedded in social structures, so any serious attempts to rectify our racist history will necessarily involve structural reform; diversity seminars are not reparations.

America can still choose solidarity. The Black experience shows the way.

Today, elite law schools across the country offer courses in critical race theory. Yale Law regularly hosts a critical race theory conference, and UCLA Law’s critical race studies program organizes an annual symposium with speakers from various disciplines. Contrary to critics who’ve portrayed the idea as mere leftist folderol, these are scholarly efforts to assess the impact of race in the law and society. As an academic school of thought, you can take critical race theory or leave it — and many do.

All of this came from instigator Christopher Rufo, whose story I will get to in a bit. He's the wank that suggested that " the ideology of the Ku Klux Klan is 'a simple transposition of critical race theory’s basic tenets'” (Hoadley-Brill).

How is that not a red flag for anyone that they are moving in to the land of crazy?

Wha??????????

But it's all denialism. As I stated previously, understanding the deep roots of racism in our culture and how whites are complicit in it either as actors or as silent bystanders (silence is its own kind of complicity) is a painful process.

For most, the moral panic around critical race theory isn’t that intense, but the phrase can still be a stand-in for those who chafe at even the notion of systemic racism. Think of the aggrieved letter written by a parent at New York’s Brearley School, and published by polemicist Bari Weiss, ripping the school for “adopting critical race theory” and shrinking systemic racism to this definition: “Systemic racism, properly understood, is segregated schools and separate lunch counters. It is the interning of Japanese and the exterminating of Jews. . . . We have not had systemic racism against Blacks in this country since the civil rights reforms of the 1960s.”

And, sadly, these conservative wanks are winning, and this article was published almost exactly two years ago.

By this point, the campaign against the theory, and the phrase, isn’t even camouflaged. In March, Rufo tweeted: “We have successfully frozen their brand — ‘critical race theory’ — into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perceptions. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category.” “To win the war against wokeness,” he wrote in April, “we have to create persuasive language. From now on, we should refer to critical race theory in education as ‘state-sanctioned racism.’ That’s the new weapon in the language war.” (This past week, he dialed the idea back in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, making the narrower case that the “Battle Over Critical Race Theory” isn’t about some “exercise in promoting racial sensitivity or understanding history,” but rather, he says, about shunning a “radical ideology.”)

AdvertisementStory continues below advertisementIt’s plain. Today’s attacks on critical race theory aren’t meant to rebut its main arguments. They’re meant to paint it with such broad brushstrokes that any basic effort to reckon with the causes and impact of racism in our society can be demonized and dismissed.

|

| https://sensedoubt.blogspot.com/2020/09/a-sense-of-doubt-blog-post-2034-justice.html |

"A Primer on Critical Race Theory"

My link to a PDF.

This article is a very good primer on the subject of Critical Race Theory (CRT). It's worth a read for anyone who really wants to understand it and what it actually is, how it came to be, and what it has spawned.

But nearly every opponent just wants to listen to the invective in their echo chamber and not really learn or understand anything. Their views are so warped and inaccurate that they would be comical if not so offensive, deeply troubling, and dangerous.

https://theconversation.com/critical-race-theory-what-it-is-and-what-it-isnt-162752

Critical race theory: What it is and what it isn’t

U.S. Rep. Jim Banks of Indiana sent a letter to fellow Republicans on June 24, 2021, stating: “As Republicans, we reject the racial essentialism that critical race theory teaches … that our institutions are racist and need to be destroyed from the ground up.”

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor and central figure in the development of critical race theory, said in a recent interview that critical race theory “just says, let’s pay attention to what has happened in this country, and how what has happened in this country is continuing to create differential outcomes. … Critical Race Theory … is more patriotic than those who are opposed to it because … we believe in the promises of equality. And we know we can’t get there if we can’t confront and talk honestly about inequality.”

Rep. Banks’ account is demonstrably false and typical of many people publicly declaring their opposition to critical race theory. Crenshaw’s characterization, while true, does not detail its main features. So what is critical race theory and what brought it into existence?

The development of critical race theory by legal scholars such as Derrick Bell and Crenshaw was largely a response to the slow legal progress and setbacks faced by African Americans from the end of the Civil War, in 1865, through the end of the civil rights era, in 1968. To understand critical race theory, you need to first understand the history of African American rights in the U.S.

The history

After 304 years of enslavement, then-former slaves gained equal protection under the law with passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868. The 15th Amendment, in 1870, guaranteed voting rights for men regardless of race or “previous condition of servitude.”

Between 1866 and 1877 – the period historians call “Radical Reconstruction” – African Americans began businesses, became involved in local governance and law enforcement and were elected to Congress.

This early progress was subsequently diminished by state laws throughout the American South called “Black Codes,” which limited voting rights, property rights and compensation for work; made it illegal to be unemployed or not have documented proof of employment; and could subject prisoners to work without pay on behalf of the state. These legal rollbacks were worsened by the spread of “Jim Crow” laws throughout the country requiring segregation in almost all aspects of life.

Grassroots struggles for civil rights were constant in post-Civil War America. Some historians even refer to the period from the New Deal Era, which began in 1933, to the present as “The Long Civil Rights Movement.”

The period stretching from Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which found school segregation to be unconstitutional, to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination in housing, was especially productive.

The civil rights movement used practices such as civil disobedience, nonviolent protest, grassroots organizing and legal challenges to advance civil rights. The U.S.’s need to improve its image abroad during the Cold War importantly aided these advancements. The movement succeeded in banning explicit legal discrimination and segregation, promoted equal access to work and housing and extended federal protection of voting rights. However, the movement that produced legal advances had no effect on the increasing racial wealth gap between Blacks and whites, while school and housing segregation persisted.

|

| The racial wealth gap between Blacks and whites has persisted. Here, Carde Cornish takes his son past blighted buildings in Baltimore. ‘Our race issues aren’t necessarily toward individuals who are white, but it is towards the system that keeps us all down, one, but keeps Black people disproportionally down a lot more than anybody else,’ he said. AP Photo/Matt Rourke |

What critical race theory is

Critical race theory is a field of intellectual inquiry that demonstrates the legal codification of racism in America.

Through the study of law and U.S. history, it attempts to reveal how racial oppression shaped the legal fabric of the U.S. Critical race theory is traditionally less concerned with how racism manifests itself in interactions with individuals and more concerned with how racism has been, and is, codified into the law.

There are a few beliefs commonly held by most critical race theorists.

First, race is not fundamentally or essentially a matter of biology, but rather a social construct. While physical features and geographic origin play a part in making up what we think of as race, societies will often make up the rest of what we think of as race. For instance, 19th- and early-20th-century scientists and politicians frequently described people of color as intellectually or morally inferior, and used those false descriptions to justify oppression and discrimination.

Second, these racial views have been codified into the nation’s foundational documents and legal system. For evidence of that, look no further than the “Three-Fifths Compromise” in the Constitution, whereby slaves, denied the right to vote, were nonetheless treated as part of the population for increasing congressional representation of slave-holding states.

Third, given the pervasiveness of racism in our legal system and institutions, racism is not aberrant, but a normal part of life.

Fourth, multiple elements, such as race and gender, can lead to kinds of compounded discrimination that lack the civil rights protections given to individual, protected categories. For example, Crenshaw has forcibly argued that there is a lack of legal protection for Black women as a category. The courts have treated Black women as Black, or women, but not both in discrimination cases – despite the fact that they may have experienced discrimination because they were both.

These beliefs are shared by scholars in a variety of fields who explore the role of racism in areas such as education, health care and history.

Finally, critical race theorists are interested not just in studying the law and systems of racism, but in changing them for the better.

What critical race theory is not

“Critical race theory” has become a catch-all phrase among legislators attempting to ban a wide array of teaching practices concerning race. State legislators in Arizona, Arkansas, Idaho, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas and West Virginia have introduced legislation banning what they believe to be critical race theory from schools.

But what is being banned in education, and what many media outlets and legislators are calling “critical race theory,” is far from it. Here are sections from identical legislation in Oklahoma and Tennessee that propose to ban the teaching of these concepts. As a philosopher of race and racism, I can safely say that critical race theory does not assert the following:

(1) One race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex;

(2) An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously;

(3) An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment because of the individual’s race or sex;

(4) An individual’s moral character is determined by the individual’s race or sex;

(5) An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex;

(6) An individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or another form of psychological distress solely because of the individual’s race or sex.

What most of these bills go on to do is limit the presentation of educational materials that suggest that Americans do not live in a meritocracy, that foundational elements of U.S. laws are racist, and that racism is a perpetual struggle from which America has not escaped.

Americans are used to viewing their history through a triumphalist lens, where we overcome hardships, defeat our British oppressors and create a country where all are free with equal access to opportunities.

Obviously, not all of that is true.

Critical race theory provides techniques to analyze U.S. history and legal institutions by acknowledging that racial problems do not go away when we leave them unaddressed.

|

| A Ku Klux Klan parade in Washington, D.C., in 1926. Everett Historical from www.shutterstock.com - https://theconversation.com/3-things-schools-should-teach-about-americas-history-of-white-supremacy-111347 |

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/civil-rights-reimagining-policing/a-lesson-on-critical-race-theory/

January 11, 2021 HUMAN RIGHTS

A Lesson on Critical Race Theory

by Janel George

In September 2020, President Trump issued an executive order excluding from federal contracts any diversity and inclusion training interpreted as containing “Divisive Concepts,” “Race or Sex Stereotyping,” and “Race or Sex Scapegoating.” Among the content considered “divisive” is Critical Race Theory (CRT). In response, the African American Policy Forum, led by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, launched the #TruthBeTold campaign to expose the harm that the order poses. Reports indicate that over 300 diversity and inclusion trainings have been canceled as a result of the order. And over 120 civil rights organizations and allies signed a letter condemning the executive order. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), the National Urban League (NUL), and the National Fair Housing Alliance filed a federal lawsuit alleging that the executive order violates the guarantees of free speech, equal protection, and due process. So, exactly what is CRT, why is it under attack, and what does it mean for the civil rights lawyer?

CRT is not a diversity and inclusion “training” but a practice of interrogating the role of race and racism in society that emerged in the legal academy and spread to other fields of scholarship. Crenshaw—who coined the term “CRT”—notes that CRT is not a noun, but a verb. It cannot be confined to a static and narrow definition but is considered to be an evolving and malleable practice. It critiques how the social construction of race and institutionalized racism perpetuate a racial caste system that relegates people of color to the bottom tiers. CRT also recognizes that race intersects with other identities, including sexuality, gender identity, and others. CRT recognizes that racism is not a bygone relic of the past. Instead, it acknowledges that the legacy of slavery, segregation, and the imposition of second-class citizenship on Black Americans and other people of color continue to permeate the social fabric of this nation.

In September 2020, President Trump issued an executive order excluding from federal contracts any diversity and inclusion training interpreted as containing “Divisive Concepts,” “Race or Sex Stereotyping,” and “Race or Sex Scapegoating.” Among the content considered “divisive” is Critical Race Theory (CRT). In response, the African American Policy Forum, led by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, launched the #TruthBeTold campaign to expose the harm that the order poses. Reports indicate that over 300 diversity and inclusion trainings have been canceled as a result of the order. And over 120 civil rights organizations and allies signed a letter condemning the executive order. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), the National Urban League (NUL), and the National Fair Housing Alliance filed a federal lawsuit alleging that the executive order violates the guarantees of free speech, equal protection, and due process. So, exactly what is CRT, why is it under attack, and what does it mean for the civil rights lawyer?

CRT is not a diversity and inclusion “training” but a practice of interrogating the role of race and racism in society that emerged in the legal academy and spread to other fields of scholarship. Crenshaw—who coined the term “CRT”—notes that CRT is not a noun, but a verb. It cannot be confined to a static and narrow definition but is considered to be an evolving and malleable practice. It critiques how the social construction of race and institutionalized racism perpetuate a racial caste system that relegates people of color to the bottom tiers. CRT also recognizes that race intersects with other identities, including sexuality, gender identity, and others. CRT recognizes that racism is not a bygone relic of the past. Instead, it acknowledges that the legacy of slavery, segregation, and the imposition of second-class citizenship on Black Americans and other people of color continue to permeate the social fabric of this nation.

Principles of the CRT Practice

While recognizing the evolving and malleable nature of CRT, scholar Khiara Bridges outlines a few key tenets of CRT, including:

- Recognition that race is not biologically real but is socially constructed and socially significant. It recognizes that science (as demonstrated in the Human Genome Project) refutes the idea of biological racial differences. According to scholars Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, race is the product of social thought and is not connected to biological reality.

- Acknowledgement that racism is a normal feature of society and is embedded within systems and institutions, like the legal system, that replicate racial inequality. This dismisses the idea that racist incidents are aberrations but instead are manifestations of structural and systemic racism.

- Rejection of popular understandings about racism, such as arguments that confine racism to a few “bad apples.” CRT recognizes that racism is codified in law, embedded in structures, and woven into public policy. CRT rejects claims of meritocracy or “colorblindness.” CRT recognizes that it is the systemic nature of racism that bears primary responsibility for reproducing racial inequality.

- Recognition of the relevance of people’s everyday lives to scholarship. This includes embracing the lived experiences of people of color, including those preserved through storytelling, and rejecting deficit-informed research that excludes the epistemologies of people of color.

CRT does not define racism in the traditional manner as solely the consequence of discrete irrational bad acts perpetrated by individuals but is usually the unintended (but often foreseeable) consequence of choices. It exposes the ways that racism is often cloaked in terminology regarding “mainstream,” “normal,” or “traditional” values or “neutral” policies, principles, or practices. And, as scholar Tara Yosso asserts, CRT can be an approach used to theorize, examine, and challenge the ways which race and racism implicitly and explicitly impact social structures, practices, and discourses. CRT observes that scholarship that ignores race is not demonstrating “neutrality” but adherence to the existing racial hierarchy. For the civil rights lawyer, this can be a particularly powerful approach for examining race in society. Particularly because CRT has recently come under fire, understanding CRT and some of its primary tenets is vital for the civil rights lawyer who seeks to eradicate racial inequality in this country.

The originators of CRT include Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Cheryl Harris, Richard Delgado, Patricia Williams, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Tara Yosso, among others. CRT transcends a Black/white racial binary and recognizes that racism has impacted the experiences of various people of color, including Latinx, Native Americans, and Asian Americans. As a result, different branches, including LatCrit, TribalCrit, and AsianCRT have emerged from CRT. These different branches seek to examine specific experiences of oppression. CRT challenges white privilege and exposes deficit-informed research that ignores, and often omits, the scholarship of people of color. CRT began in the legal academy in the 1970s and grew in the 1980s and 1990s. It persists as a field of inquiry in the legal field and in other areas of scholarship. Mari Matsudi described CRT as the work of progressive legal scholars seeking to address the role of racism in the law and the work to eliminate it and other configurations of subordination.

CRT grew from Critical Legal Studies (CLS), which argued that the law was not objective or apolitical. CLS was a significant departure from earlier conceptions of the law (and other fields of scholarship) as objective, neutral, principled, and dissociated from social or political considerations. Like proponents of CLS, critical race theorists recognized that the law could be complicit in maintaining an unjust social order. Where critical race theorists departed from CLS was in the recognition of how race and racial inequality were reproduced through the law. Further, CRT scholars did not share the approach of destabilizing social injustice by destabilizing the law. Many CRT scholars had witnessed how the law could be used to help secure and protect civil rights. Therefore, critical race theorists recognized that, while the law could be used to deepen racial inequality, it also held potential as a tool for emancipation and for securing racial equality.

Foundational questions that underlie CRT and the law include: How does the law construct race?; How has the law protected racism and upheld racial hierarchies?; How does the law reproduce racial inequality?; and How can the law be used to dismantle race, racism, and racial inequality?

In the field of education, Daniel Solórzano has identified tenets of CRT that, in addition to the impact of race and racism and the challenge to the dominant ideology of the objectivity of scholarship, include a commitment to social justice; centering the experiential knowledge of people of color; and using multiple approaches from a variety of disciplines to analyze racism within both historical and contemporary contexts, such as women’s studies, sociology, history, law, psychology, film, theater, and other fields.

Some of the most compelling demonstrations of how racism has been replicated through systems is within the education system. Many can recall images of troops escorting nine Black students to integrate Little Rock Central High School. Or Ruby Bridges being escorted into a New Orleans Elementary School by armed guards six years after the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated racially segregated education in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Those moments are just snapshots of the intersection of racism, the law, and the education system. This article provides just a snapshot of CRT, and the following explanation is a glimpse of the application of CRT in education. But the explanation below seeks to capture how CRT applies to the education system, particularly in addressing how racial inequality persists in the post–civil rights era.

While recognizing the evolving and malleable nature of CRT, scholar Khiara Bridges outlines a few key tenets of CRT, including:

- Recognition that race is not biologically real but is socially constructed and socially significant. It recognizes that science (as demonstrated in the Human Genome Project) refutes the idea of biological racial differences. According to scholars Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, race is the product of social thought and is not connected to biological reality.

- Acknowledgement that racism is a normal feature of society and is embedded within systems and institutions, like the legal system, that replicate racial inequality. This dismisses the idea that racist incidents are aberrations but instead are manifestations of structural and systemic racism.

- Rejection of popular understandings about racism, such as arguments that confine racism to a few “bad apples.” CRT recognizes that racism is codified in law, embedded in structures, and woven into public policy. CRT rejects claims of meritocracy or “colorblindness.” CRT recognizes that it is the systemic nature of racism that bears primary responsibility for reproducing racial inequality.

- Recognition of the relevance of people’s everyday lives to scholarship. This includes embracing the lived experiences of people of color, including those preserved through storytelling, and rejecting deficit-informed research that excludes the epistemologies of people of color.

CRT does not define racism in the traditional manner as solely the consequence of discrete irrational bad acts perpetrated by individuals but is usually the unintended (but often foreseeable) consequence of choices. It exposes the ways that racism is often cloaked in terminology regarding “mainstream,” “normal,” or “traditional” values or “neutral” policies, principles, or practices. And, as scholar Tara Yosso asserts, CRT can be an approach used to theorize, examine, and challenge the ways which race and racism implicitly and explicitly impact social structures, practices, and discourses. CRT observes that scholarship that ignores race is not demonstrating “neutrality” but adherence to the existing racial hierarchy. For the civil rights lawyer, this can be a particularly powerful approach for examining race in society. Particularly because CRT has recently come under fire, understanding CRT and some of its primary tenets is vital for the civil rights lawyer who seeks to eradicate racial inequality in this country.

The originators of CRT include Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Cheryl Harris, Richard Delgado, Patricia Williams, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Tara Yosso, among others. CRT transcends a Black/white racial binary and recognizes that racism has impacted the experiences of various people of color, including Latinx, Native Americans, and Asian Americans. As a result, different branches, including LatCrit, TribalCrit, and AsianCRT have emerged from CRT. These different branches seek to examine specific experiences of oppression. CRT challenges white privilege and exposes deficit-informed research that ignores, and often omits, the scholarship of people of color. CRT began in the legal academy in the 1970s and grew in the 1980s and 1990s. It persists as a field of inquiry in the legal field and in other areas of scholarship. Mari Matsudi described CRT as the work of progressive legal scholars seeking to address the role of racism in the law and the work to eliminate it and other configurations of subordination.

CRT grew from Critical Legal Studies (CLS), which argued that the law was not objective or apolitical. CLS was a significant departure from earlier conceptions of the law (and other fields of scholarship) as objective, neutral, principled, and dissociated from social or political considerations. Like proponents of CLS, critical race theorists recognized that the law could be complicit in maintaining an unjust social order. Where critical race theorists departed from CLS was in the recognition of how race and racial inequality were reproduced through the law. Further, CRT scholars did not share the approach of destabilizing social injustice by destabilizing the law. Many CRT scholars had witnessed how the law could be used to help secure and protect civil rights. Therefore, critical race theorists recognized that, while the law could be used to deepen racial inequality, it also held potential as a tool for emancipation and for securing racial equality.

Foundational questions that underlie CRT and the law include: How does the law construct race?; How has the law protected racism and upheld racial hierarchies?; How does the law reproduce racial inequality?; and How can the law be used to dismantle race, racism, and racial inequality?

In the field of education, Daniel Solórzano has identified tenets of CRT that, in addition to the impact of race and racism and the challenge to the dominant ideology of the objectivity of scholarship, include a commitment to social justice; centering the experiential knowledge of people of color; and using multiple approaches from a variety of disciplines to analyze racism within both historical and contemporary contexts, such as women’s studies, sociology, history, law, psychology, film, theater, and other fields.

Some of the most compelling demonstrations of how racism has been replicated through systems is within the education system. Many can recall images of troops escorting nine Black students to integrate Little Rock Central High School. Or Ruby Bridges being escorted into a New Orleans Elementary School by armed guards six years after the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated racially segregated education in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Those moments are just snapshots of the intersection of racism, the law, and the education system. This article provides just a snapshot of CRT, and the following explanation is a glimpse of the application of CRT in education. But the explanation below seeks to capture how CRT applies to the education system, particularly in addressing how racial inequality persists in the post–civil rights era.

Education and CRT

Segregated schooling is a particularly profound and timely demonstration of the persistence of systemic racism in education. For example, Brown is often couched in terms of American exceptionalism. But Gloria Ladson-Billings and other CRT originators in the field of education recognize that Brown was the culmination of over a century of legal challenges to segregated schooling and second-class citizenship and far from a natural occurrence or inevitable result of racial progress. The late Harvard Law Professor Derrick Bell, in Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma, noted that the Fourteenth Amendment alone could not effectively promote racial equality for Black people where such a remedy threatened the superior social status of wealthy white people. Further, Bell noted that Brown was decided the way it was because of what he termed “interest convergence,” which is the recognition that the interests of Black people in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of white people.

Therefore, Brown’s legal invalidation of racial segregation in education held some benefits for white policymakers as well as for Black students. Chief among these, Bell argued, was not the moral imperative of ending legal segregation but restoring the credibility of America’s image abroad. As the nation waged a Cold War, it became increasingly difficult for the country to justify its racial caste system, Bell observed. Further, the Brown ruling was limited in its relief, and the persistence of racial inequality following the civil rights era implicates the law in maintaining racial inequality. For example, the Supreme Court failed to outline a specific remedy to achieve integrated education. As Ladson-Billings notes in Landing on the Wrong Note: The Price We Paid for Brown of Brown II decided in 1955, it can be seen as a combination of flawed compromises that combined a denouncement of legal segregation with a limited and unworkable remedy. It took years of subsequent litigation over the ensuing decades until the Court finally mandated that school districts act to uproot all vestiges of segregation “root and branch.”

A particular limitation of legal efforts to address racial inequality has been the inability of many legal mandates to reach the covert and insidious nature of de facto racism. This has proved that eradicating racial inequality in education is not merely an exercise in ending legal segregation. For example, achieving racial balance, as Bell asserted, did not obviate the need to address other systemic practices that perpetuate racial inequality within diverse schools, such as the loss of Black faculty and administrators, many of whom lost their jobs in the wake of Brown as retribution for aiding school desegregation efforts. Bell observed that changing demographic patterns, white flight, and the reluctance of the courts to urge the necessary degree of social reform rendered further progress in Brown virtually impossible.

The limitations of legal interventions have led to current manifestations of racial inequality in education, including:

- The predominance of curriculum that excludes the history and lived experiences of Americans of color and imposes a dominant white narrative of history;

- Deficit-oriented instruction that characterizes students of color as in need of remediation;

- Narrow assessments, the results of which are used to confirm narratives about the ineducability of children of color;

- School discipline policies that disproportionately impact students of color and compromise their educational outcomes (such as dress code policies prohibiting natural Black hairstyles);

- School funding inequities, including the persistent underfunding of property-poor districts, many of which are composed primarily of children of color; and

- The persistence of racially segregated education.

School funding inequities are exemplified in many racially and socioeconomically isolated districts, such as Detroit’s public schools. In 1940, shortly before Verda Bradley arrived in Detroit, Black Americans comprised 9.2 percent of the city’s population. Over 30 years later, when her children went to school, Black Americans comprised 44.5 percent of the city’s population. The ratio of Black students to white students was 58 to 41 in 1967. Seeking to desegregate the city’s schools, Bradley and other parents who were represented by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People alleged that Michigan maintained a racially segregated public school system through policies that isolated Black students within the city’s public schools. Due to racially discriminatory housing practices, Black families were excluded from the surrounding suburbs populated by white families that fled the city to avoid integrating the schools. However, in Milliken v. Bradley, the Supreme Court rejected a desegregation plan that encompassed Detroit’s public schools and the surrounding all-white suburbs. In exempting the surrounding suburban districts from the desegregation plan, the Court held that they were not required to be part of the desegregation plan because district lines had not been drawn with “racist intent” and the surrounding suburbs were not responsible for the segregation within the city’s schools. The Court left Detroit to desegregate within itself. In his prescient dissent, Thurgood Marshall observed, “The Detroit-only plan has no hope of achieving actual desegregation. . . . Instead, Negro children will continue to attend all-Negro schools. The very evil that Brown was aimed at will not be cured but will be perpetuated.”

Consequently, in 2000, the ratio of Black students to white students in Detroit’s public schools was 91 to 4. The city’s racially isolated public schools are also profoundly under-resourced. Recent litigation—Gary B. v. Whitmer—brought on behalf of students in Detroit’s public schools illuminates the state of the schools in the decades following Milliken. In their complaint, the plaintiffs describe deteriorating facilities that lack heat and are infested with vermin. They describe the absence of qualified educators that resulted in a middle schooler serving as a substitute teacher. But students like the Gary B. plaintiffs (and students in similarly racially isolated and under-resourced districts) are left with little recourse given that the Supreme Court held in 1973’s San Antonio v. Rodriguez that there is no federal right to education.

Instead, the Gary B. plaintiffs brought a novel claim alleging that they were entitled to a minimum level of education that enabled them to achieve at least a basic level of literacy. The decision of the Court of Appeals in favor of the plaintiffs was ultimately set aside, and the state of Michigan reached a settlement with the plaintiffs. However, from a CRT perspective, the case is instructive about how the law can reproduce racial inequality. By rejecting a desegregation plan that sought to transcend the racial divisions imposed by discriminatory housing practices, the Court essentially foreclosed the possibility of implementing a workable desegregation strategy, and racial and economic inequality persisted unabated. CRT recognizes the inevitability of the segregated and under-resourced schools at issue in the Gary B. litigation, given Milliken’s indifference to the nature of covert discrimination decades earlier.

Segregated schooling is a particularly profound and timely demonstration of the persistence of systemic racism in education. For example, Brown is often couched in terms of American exceptionalism. But Gloria Ladson-Billings and other CRT originators in the field of education recognize that Brown was the culmination of over a century of legal challenges to segregated schooling and second-class citizenship and far from a natural occurrence or inevitable result of racial progress. The late Harvard Law Professor Derrick Bell, in Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma, noted that the Fourteenth Amendment alone could not effectively promote racial equality for Black people where such a remedy threatened the superior social status of wealthy white people. Further, Bell noted that Brown was decided the way it was because of what he termed “interest convergence,” which is the recognition that the interests of Black people in achieving racial equality will be accommodated only when it converges with the interests of white people.

Therefore, Brown’s legal invalidation of racial segregation in education held some benefits for white policymakers as well as for Black students. Chief among these, Bell argued, was not the moral imperative of ending legal segregation but restoring the credibility of America’s image abroad. As the nation waged a Cold War, it became increasingly difficult for the country to justify its racial caste system, Bell observed. Further, the Brown ruling was limited in its relief, and the persistence of racial inequality following the civil rights era implicates the law in maintaining racial inequality. For example, the Supreme Court failed to outline a specific remedy to achieve integrated education. As Ladson-Billings notes in Landing on the Wrong Note: The Price We Paid for Brown of Brown II decided in 1955, it can be seen as a combination of flawed compromises that combined a denouncement of legal segregation with a limited and unworkable remedy. It took years of subsequent litigation over the ensuing decades until the Court finally mandated that school districts act to uproot all vestiges of segregation “root and branch.”

A particular limitation of legal efforts to address racial inequality has been the inability of many legal mandates to reach the covert and insidious nature of de facto racism. This has proved that eradicating racial inequality in education is not merely an exercise in ending legal segregation. For example, achieving racial balance, as Bell asserted, did not obviate the need to address other systemic practices that perpetuate racial inequality within diverse schools, such as the loss of Black faculty and administrators, many of whom lost their jobs in the wake of Brown as retribution for aiding school desegregation efforts. Bell observed that changing demographic patterns, white flight, and the reluctance of the courts to urge the necessary degree of social reform rendered further progress in Brown virtually impossible.

The limitations of legal interventions have led to current manifestations of racial inequality in education, including:

- The predominance of curriculum that excludes the history and lived experiences of Americans of color and imposes a dominant white narrative of history;

- Deficit-oriented instruction that characterizes students of color as in need of remediation;

- Narrow assessments, the results of which are used to confirm narratives about the ineducability of children of color;

- School discipline policies that disproportionately impact students of color and compromise their educational outcomes (such as dress code policies prohibiting natural Black hairstyles);

- School funding inequities, including the persistent underfunding of property-poor districts, many of which are composed primarily of children of color; and

- The persistence of racially segregated education.

School funding inequities are exemplified in many racially and socioeconomically isolated districts, such as Detroit’s public schools. In 1940, shortly before Verda Bradley arrived in Detroit, Black Americans comprised 9.2 percent of the city’s population. Over 30 years later, when her children went to school, Black Americans comprised 44.5 percent of the city’s population. The ratio of Black students to white students was 58 to 41 in 1967. Seeking to desegregate the city’s schools, Bradley and other parents who were represented by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People alleged that Michigan maintained a racially segregated public school system through policies that isolated Black students within the city’s public schools. Due to racially discriminatory housing practices, Black families were excluded from the surrounding suburbs populated by white families that fled the city to avoid integrating the schools. However, in Milliken v. Bradley, the Supreme Court rejected a desegregation plan that encompassed Detroit’s public schools and the surrounding all-white suburbs. In exempting the surrounding suburban districts from the desegregation plan, the Court held that they were not required to be part of the desegregation plan because district lines had not been drawn with “racist intent” and the surrounding suburbs were not responsible for the segregation within the city’s schools. The Court left Detroit to desegregate within itself. In his prescient dissent, Thurgood Marshall observed, “The Detroit-only plan has no hope of achieving actual desegregation. . . . Instead, Negro children will continue to attend all-Negro schools. The very evil that Brown was aimed at will not be cured but will be perpetuated.”

Consequently, in 2000, the ratio of Black students to white students in Detroit’s public schools was 91 to 4. The city’s racially isolated public schools are also profoundly under-resourced. Recent litigation—Gary B. v. Whitmer—brought on behalf of students in Detroit’s public schools illuminates the state of the schools in the decades following Milliken. In their complaint, the plaintiffs describe deteriorating facilities that lack heat and are infested with vermin. They describe the absence of qualified educators that resulted in a middle schooler serving as a substitute teacher. But students like the Gary B. plaintiffs (and students in similarly racially isolated and under-resourced districts) are left with little recourse given that the Supreme Court held in 1973’s San Antonio v. Rodriguez that there is no federal right to education.

Instead, the Gary B. plaintiffs brought a novel claim alleging that they were entitled to a minimum level of education that enabled them to achieve at least a basic level of literacy. The decision of the Court of Appeals in favor of the plaintiffs was ultimately set aside, and the state of Michigan reached a settlement with the plaintiffs. However, from a CRT perspective, the case is instructive about how the law can reproduce racial inequality. By rejecting a desegregation plan that sought to transcend the racial divisions imposed by discriminatory housing practices, the Court essentially foreclosed the possibility of implementing a workable desegregation strategy, and racial and economic inequality persisted unabated. CRT recognizes the inevitability of the segregated and under-resourced schools at issue in the Gary B. litigation, given Milliken’s indifference to the nature of covert discrimination decades earlier.

CRT and a Call to Action for Civil Rights Lawyers

The example of application of CRT to education in the case of Milliken illustrates how CRT recognizes the role of the law in perpetuating racial inequality. Employing a CRT framework necessitates interrogation of systems and structures in which we function. The Milliken example also implicates the impact of discriminatory housing policies and school financing systems in perpetuating racially isolated and under-resourced schools in Detroit and recognizes that education policy does not operate in a vacuum.

Another important consideration is that many of our nation’s systems and structures—including the legal system—were created when people of color were denied full participation in American society. Therefore, as many critical race theorists have noted, CRT calls for a radical reordering of society and a reckoning with the structures and systems that intersect to perpetuate racial inequality.

For civil rights lawyers, this necessitates an examination of the legal system and the ways it reproduces racial injustice. It also necessitates a rethinking of interpersonal interactions, including the role of the civil rights lawyer. It means a centering of the stories and voices of those who are impacted by the laws, systems, and structures that so many civil rights advocates work to improve. It requires the abandonment of a deficit approach that perceives those impacted by unjust laws and policies as deficient, defective, or helpless. Instead, we ought to recognize that these individuals have stories, histories, and knowledge that are worth acknowledging, learning about, and centering. Particularly in devising legal and policy interventions to address racial inequality, CRT calls for considering unintended consequences of proposed remedies, addressing intersecting policies and structures, and acting intentionally to ensure that harm is not further replicated by the legal system. Most of all, CRT demands challenging the status quo of racial inequality that has persisted for far too long in this nation and exploring how the law and lawyers can help to finally upend it.

Like any other approach, CRT can be misunderstood and misapplied. It has been distorted and attacked. And it continues to change and evolve. The hope in CRT is in its recognition that the same policies, structures, and scholarship that can function to disenfranchise and oppress so many also holds the potential to emancipate and empower many. It provides a lens through which the civil rights lawyer can imagine a more just nation.

The example of application of CRT to education in the case of Milliken illustrates how CRT recognizes the role of the law in perpetuating racial inequality. Employing a CRT framework necessitates interrogation of systems and structures in which we function. The Milliken example also implicates the impact of discriminatory housing policies and school financing systems in perpetuating racially isolated and under-resourced schools in Detroit and recognizes that education policy does not operate in a vacuum.

Another important consideration is that many of our nation’s systems and structures—including the legal system—were created when people of color were denied full participation in American society. Therefore, as many critical race theorists have noted, CRT calls for a radical reordering of society and a reckoning with the structures and systems that intersect to perpetuate racial inequality.

For civil rights lawyers, this necessitates an examination of the legal system and the ways it reproduces racial injustice. It also necessitates a rethinking of interpersonal interactions, including the role of the civil rights lawyer. It means a centering of the stories and voices of those who are impacted by the laws, systems, and structures that so many civil rights advocates work to improve. It requires the abandonment of a deficit approach that perceives those impacted by unjust laws and policies as deficient, defective, or helpless. Instead, we ought to recognize that these individuals have stories, histories, and knowledge that are worth acknowledging, learning about, and centering. Particularly in devising legal and policy interventions to address racial inequality, CRT calls for considering unintended consequences of proposed remedies, addressing intersecting policies and structures, and acting intentionally to ensure that harm is not further replicated by the legal system. Most of all, CRT demands challenging the status quo of racial inequality that has persisted for far too long in this nation and exploring how the law and lawyers can help to finally upend it.

Like any other approach, CRT can be misunderstood and misapplied. It has been distorted and attacked. And it continues to change and evolve. The hope in CRT is in its recognition that the same policies, structures, and scholarship that can function to disenfranchise and oppress so many also holds the potential to emancipate and empower many. It provides a lens through which the civil rights lawyer can imagine a more just nation.

So what happened?

I subscribed to the New Yorker just to get this next article at the link directly below. If you read nothing else, read this.

As Rufo eventually came to see it, conservatives engaged in the culture war had been fighting against the same progressive racial ideology since late in the Obama years, without ever being able to describe it effectively. “We’ve needed new language for these issues,” Rufo told me, when I first wrote to him, late in May. “ ‘Political correctness’ is a dated term and, more importantly, doesn’t apply anymore. It’s not that elites are enforcing a set of manners and cultural limits, they’re seeking to reengineer the foundation of human psychology and social institutions through the new politics of race, It’s much more invasive than mere ‘correctness,’ which is a mechanism of social control, but not the heart of what’s happening. The other frames are wrong, too: ‘cancel culture’ is a vacuous term and doesn’t translate into a political program; ‘woke’ is a good epithet, but it’s too broad, too terminal, too easily brushed aside. ‘Critical race theory’ is the perfect villain,” Rufo wrote.Rufo wrote about his views, won himself time on "Tucker Carlson Tonight" on Fox, the worst of the propaganda of the since fired "journalist." Right after his appearance with Tucker, he received a call from Mark Meadows that President Trump has seen the segment and was ready to take action to ban CRT.

This is where I get the rallying cry for our own fight against the censors. What they say we're doing -- the "woke" crowd -- is exactly what they are doing. They weaponized government, such as what Ron DeSantis has continued to do in Florida.

"Core American Values" would be ones of truth, freedom, and liberty for all not just a select few. The backwards idea that "woke" ideology is racist against white people is just a ridiculous idea, and yet it resonates with overtly racist people and even those in the "white fragility" mode who don't think they are racist, don't think they contribute to racist power structures.

he next day, I spoke by phone with Kimberlé Crenshaw, a law professor with appointments at Columbia and U.C.L.A., and perhaps the most prominent figure associated with critical race theory—a term she had, long ago, coined. Crenshaw sounded slightly exasperated by how much coverage focussed on the semantic question of what critical race theory meant rather than the political one about the nature of the campaign against it. “It should go without saying that what they are calling critical race theory is a whole range of things, most of which no one would sign on to, and many of the things in it are simply about racism,” she said. When I asked what was new to her about the conservative movement against critical race theory, she said that the main thing was that it had been championed last fall not by conservative academics but by Donald Trump, then the President of the United States, and by many leading conservative political and media figures. But the broader pattern was not new, or surprising. “Reform itself creates its own backlash, which reconstitutes the problem in the first place,” Crenshaw said, noting that she’d made this argument in her first law-review article, in 1988. George Floyd’s murder had led to “so many corporations and opinion-shaping institutions making statements about structural racism”—creating a new, broader anti-racist alignment, or at least the potential for one. “This is a post-George Floyd backlash,” Crenshaw said. “The reason why we’re having this conversation is that the line of scrimmage has moved.”

BACKLASH.

And yet, trying to control education, brings its own hazards.

Are teachers and principals going to quit over these authoritarian controls being placed on what they can teach and how they must police teachers?

That climate has had a chilling effect on teachers and school administrators, affecting the way they approach their jobs. A principal of a high school in Ohio—where some parents demanded banning Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye—said he has stopped meeting with parents alone in his office because he assumes he is “going to be accused of something I didn’t do at some point.” His staff is also concerned about addressing certain topics such as Jim Crow and the civil rights movement in the classroom. “We are trying to weather this storm and see if we can get through it,” he said. In some cases, principals have actively discouraged teachers from discussing politics or current events so, as one principal put it, “our school can function with as little disruption as possible and hopefully without violence.”

Teachers in high schools most affected by conflicts also tended to be the ones less likely to receive the support and professional development necessary to deal with these situations, the researchers concluded. Interviewees reported that fearing the hostility toward schools may make it harder to find and retain teachers, particularly in rural areas. “Something needs to change or else we will all quit,” said a principal in California. Another in Nevada observed, “I know I’m not the only one who is counting days now until retirement, and I’m getting closer.”

|

| https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2022/11/national-survey-principals-something-needs-to-change-or-else-we-will-all-quit/ |

Florida colleges will no longer "fund or support" critical race theory. https://t.co/QtdrPwWaCJ via @MotherJones

— gmrstudios (@gmrstudios) January 20, 2023

An investigation by UnKoch My Campus found that both the Heritage Foundation and the American Legislative Exchange Council — major proponents of "school choice" — have been pushing for anti-Critical Race theory Bills across the United States.

At the moment, there is a coordinated effort in states across the country to pass bills attempting to ban the teaching of CRT in public schools. The Koch-funded Heritage Foundation is leading the push, claiming that CRT “ is destructive and rejects the fundamental ideas on which our constitutional republic is based.” In their quest to control what is taught in schools, Heritage Action for America, an affiliate of the Heritage Foundation think tank, created a toolkit to get folks to push antiCRT legislation in their individual states.

Um....no.

White people panicking to protect their power:

The NBC News reporting on CRT backlash is important because it makes clear that the fights currently happening in school districts nationwide are an extension of those desperate grasps to maintain power and limit interactions with people of color. Sure, a white parent shouting at a school board meeting because they don’t want their child learning the truth about racial inequality isn’t as blatant as the violence carried out by the Klan. But it is motivated by the same desire to protect whiteness, its stature, and the privilege it bestows

Officials in Republican-controlled states across America are proposing numerous laws to ban teachers from emphasizing the role of systemic racism. Legislation aiming to curb how teachers talk about race has been considered by at least 15 states, according to research by Education Week.

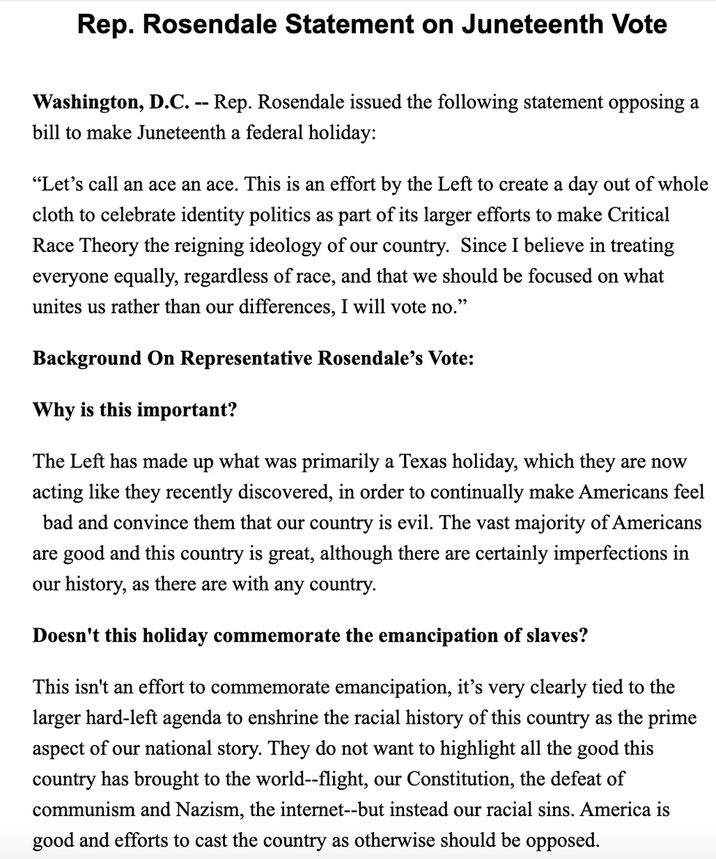

Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida, has described CRT as “state-sanctioned racism”.

Brad Little, the governor of Idaho, signed into law a measure banning public schools from teaching CRT, which it claimed will “exacerbate and inflame divisions on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, national origin, or other criteria in ways contrary to the unity of the nation and the wellbeing of the state of Idaho and its citizens”.

Red states are also targeting the 1619 Project, a series by the New York Times which contends that modern American history began with the arrival of enslaved people four centuries ago and examines that legacy.

Republicans are expected to use the Youngkin formula to woo suburban voters in next year’s midterm elections for Congress.

But hope is not lost.

And the student government at the University of Oregon wants to make study of Critical Race Theory a graduation requirement.

Apparently, it is surely too much to expect people oppose something to have an understanding of it that comes from reality and not from the propaganda machine that is Fox "News."

What they all seem to want is their version of reality, the heart of the Make America Great Again movement, this ideal of Americana that never existed, or really only existed for some white people and mostly on television.

What makes this fight so convoluted is that the opponents to CRT and DEI work feel that they are defending America, truth, and freedom against the very existential threat that they themselves pose.

I am emboldened to discuss these issues in my class rooms, at my college, on this blog, and in my own DEI work in my community.

And that's not all that I have to share today.

Check out the rest of the content I have loaded here.

https://www.wonkette.com/f-ck-matt-rosendale-in-the-eyeholes-of-his-white-hood-a-letter-to-my-congressman

https://www.wonkette.com/holiday-marking-end-of-slavery-very-divisive-say-assholes

General Defends Critical Race Theory in

the Military Against Rep. Matt Gaetz. Nobody Defended Gaetz Against Twitter,

Though

What happens when a congressman under

investigation for sex trafficking questions a military general on curriculum

taught in the military? He 'Gaetz' roasted.

On Wednesday, elected officials and military

officials met for a House Armed Services Committee hearing to discuss the 2022

Defense Department budget—at least that’s what it would have been if Rep. Matt

Gaetz and other Republicans weren’t so hellbent on turning it into an

anti-Critical Race Theory interrogation as if they felt the Defense

Department’s main concern should be defending white people’s fragile-ass

feelings. Fortunately, there was a top military general present at the meeting

to poignantly address Gaetz’ concerns.

NPR reports that the

chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, took the time to

respond to the guy who would be more concerned with studies on Critical Paying-for-Sex-With-Minors Theory if he

had his priorities straight.

“I do think it’s important for those of us in

uniform to be open-minded and to be widely read, and the United States Military

Academy is a University,” Milley said. “And it is important that we train and

understand. And I want to understand white rage, and I’m white, and I want to

understand it. So what is it that caused thousands of people to assault this

building and try to overturn the Constitution of the United States of America?

What caused that? I want to find that out.”

Already, Milley is being nicer than he needed

to be. You don’t have to study CRT to understand what happened during the

Caucasian Can’t-Coup-Right rebellion at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6—you just have

to understand that Republicans be lying and their constituents are idiots.

Anyway, carry on, General.

“I’ve read Mao Zedong. I’ve

read Karl Marx. I’ve read Lenin. That doesn’t make me a communist. So what is

wrong with understanding—having some situational understanding about the

country for which we are here to defend?” Milley continued. “And I personally

find it offensive that we are accusing the United States military, our general

officers, our commissioned, noncommissioned officers of being, quote, ‘woke’ or

something else, because we’re studying some theories that are out there.”

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2306.28 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2917 days ago

No comments:

Post a Comment