A Sense of Doubt blog post #3851 - Getting to the Truth about the Border and Immigration

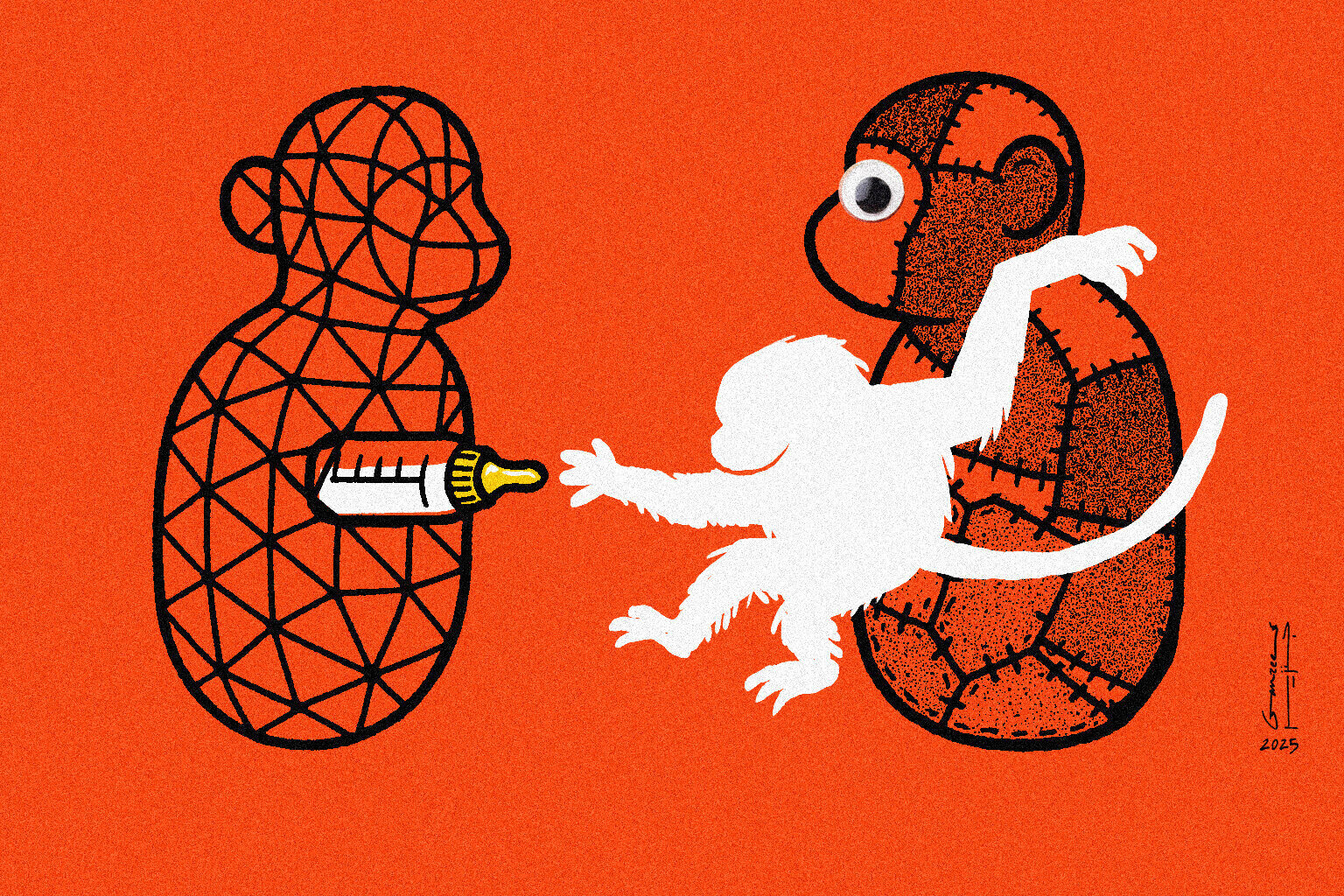

What happens when a president has his own personal militia?

Disgusting.

Trump called “many” of the undocumented immigrants “Criminals, who are MAIMING and KILLING our people!” The available data on crime rates among undocumented immigrants compared with the general population is incomplete, but an analysis by the Republican-led House Judiciary Committee concluded that about 10 percent of immigrants in removal proceedings had criminal convictions or pending charges.

At another point, Trump defended his opposition to a bipartisan bill to add emergency border authorities and funding, which Harris said he had blocked to deprive the administration of a politically beneficial accomplishment. Trump argued the legislation was unnecessary because Biden and Harris “could have just said, ‘CLOSE THE BORDER!’ like I did.” Illegal border crossings fell last month to the lowest level in four years, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data.

It Was Never Just About Crime

Ms. Flores, a lawyer, was an immigration policy adviser in the Obama and Biden administrations. She wrote from Washington, where she lives.

I was sitting on a restaurant patio on Capitol Hill with a

friend last Monday when a motorist was pulled over by local police officers

right in front of us. Within minutes, unmarked cars and federal agents — some

wearing vests marked with the initials of Homeland Security Investigations and

the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives — surrounded his

vehicle. Once outside the car, he was placed in handcuffs. He was released

after several concerned diners approached the agents.

A few days before that, I stepped outside to walk my dog and

was surprised to see Homeland Security Investigations agents patrolling my

block. By the time I got back to my apartment, they had surrounded a young

woman in front of my building. She was not resisting arrest. The agents placed

her in hand and leg cuffs bound together by chains. My neighbors and I watched

as they whisked her away in an unmarked vehicle.

I don’t know who these people were or why they were

targeted. But I’ve lived in Washington for over a decade, and I have never seen

anything as chaotic as this on our streets. Most federal agents — like the ones

I saw from H.S.I. and A.T.F. — do not normally conduct immigration checks or

pull over drivers for traffic violations. Their job is to dismantle drug cartels, arrest arms traffickers and combat child exploitation and

human trafficking rings in the United States.

President Trump said the takeover of policing and the

deployment of National Guard members here were needed to restore law and order. Then Pam Bondi, the attorney

general, pointed to district officials’ unwillingness to cooperate with

immigration officials.

The administration has threatened to deploy federal agents

to other

cities, where the White House has amplified concerns about crime,

criticized sanctuary policies and challenged political opposition. On Monday

the president issued an executive

order to create specially trained National Guard units that could be

deployed in all 50 states in the name of public safety.

These increasingly muddled objectives point to a broader

agenda: The president may be using Washington as a testing ground for expanding

federal control over local law enforcement nationwide. Once that infrastructure

is in place, little would prevent it from being turned against civilians.

While the violent crime rate in my adopted city is the lowest it’s been in years, Washington, like so many

cities, still has a long way to go in making people feel safe. Many residents,

including me, don’t think the city has done enough to reduce gun violence,

combat homelessness or address youth crime.

Still, if Mr. Trump truly cared about the well-being of the

residents, he would instead work with Congress to restore the $1.1 billion it

cut from the city’s budget — funds that would have gone to community services

that advance public safety, such as the Emergency

Rental Assistance Program, youth mental health programming and support for victims of domestic violence.

But it seems the president cares less about reducing crime

than he does about using federal law enforcement to chill dissent or retaliate

against people who question his agenda. One way we’re seeing this play out is

the use of immigration officials to arrest or try to intimidate elected

officials who are simply doing their job.

This month, Ms. Bondi sent a letter to over 30 mayors and governors threatening to prosecute them

for not being sufficiently supportive of immigration enforcement. On Aug.

14, Border

Patrol agents showed up in downtown Los Angeles at a rally and press

event that Gov. Gavin Newsom was holding on congressional redistricting.

None of these people are threats to public safety or

national security, which Mr. Trump is claiming to be his concern. These

individuals are all being caught in the web of the president’s federal

enforcement machine.

A Washington Post/Schar School poll conducted last

week found that a majority of residents said they opposed

the president’s moves. To the public, these arrests appear arbitrary, fueling

tense scenes across the city, where residents are angrily shouting at agents

and National Guard members, demanding they get out. Grand juries have declined

to issue indictments in certain cases, including one in which a man was

accused of throwing a sandwich at a federal agent.

While all this is unfolding in our city, the local economy

is taking a hit. Businesses, especially bars and restaurants, have reported a

decrease in revenue and foot traffic. Data from OpenTable shows that since the

president federalized our police department, restaurants here have experienced

a 24

percent drop in reservations compared with the same time last year.

The president was never supposed to have a personal militia. Members of Congress took an oath to

defend the Constitution and uphold our democracy, not give the president

unfettered resources to police civilians. At a minimum, they should back the

resolution introduced by Representatives Jamie Raskin and Eleanor Holmes Norton

to terminate the crime emergency Mr. Trump declared and condemn the chaos this

federal deployment has caused. Only 56 Democrats have cosponsored the

resolution so far.

Mr. Trump doesn’t make anyone safer by sending National

Guard members and federal agents into cities. Instead, he’s sowing confusion

and stretching presidential power well beyond its constitutional limits. These

moves are also a misuse of the men and women who joined the National Guard or

federal law enforcement agencies to defend the country — not to intimidate

their fellow citizens or to pick up trash around Lafayette Park.

Do we really want to live in a country where the president

can unilaterally deploy federal forces into cities that neither need nor

request them? If we allow this expansion of power to go unchecked, we risk a

future in which those federal agents can be turned against any one of us.

From 'self-deportation' to the Alien Enemies Act: a guide to all of Trump's new deportation tactics — and the real people affected by them

How to make sense of the president's immigration crackdown.

During the 2024 campaign, President Trump promised to launch an unprecedented mass deportation effort if reelected — a push that, he said, could ultimately affect millions of people who entered the United States illegally.

Since returning to the White House in January, Trump has issued a number of orders meant to expand removals. The most recent came on Monday, with the White House announcing that each immigrant who decides to "self-deport" will get a $1,000 stipend and a flight back to their home country.

But Trump’s crackdown has created controversy — and some contradictory effects.

In late April, a 4-year-old and a 7-year-old with U.S. citizenship were deported alongside their mother to Honduras on the same day a 2-year-old girl was sent there “with no meaningful process” and against the wishes of her father, according to a federal judge.

Another U.S. citizen — Jose Hermosillo, a 19-year-old from New Mexico with learning disabilities — was held for 10 days at an Arizona detention facility after suffering from a seizure.

And for months, the saga of Kilmar Abrego Garcia — the 29-year-old Maryland man who was deported to a prison in El Salvador in defiance of a withholding order forbidding his removal — has dominated headlines and consumed the courts. At first, the Trump administration acknowledged in a March 31 court filing that it had mistakenly deported Abrego Garcia; now it’s justifying Abrego Garcia’s removal and insisting that it does not have to comply with various court orders demanding his return to the U.S.

In part as a result of such stories, apprehensions on the U.S.-Mexico border — which were already falling under former President Joe Biden — have plummeted to their lowest level in decades since Trump took office.

But with fewer easy, newly arrived targets, this means Trump is deporting people at a slower pace than Biden was — which may explain why his administration keeps ratcheting up pressure on agents and catching noncriminals in its crosshairs.

Here’s a guide to Trump's confusing new deportation tactics — and the real people affected by them.

Incentivizing 'self-deportation'

What's changed under Trump: Self-deportation isn't new; Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney first popularized the idea in 2012. "We're not going to round people up," Romney said at the time. "The answer is self-deportation, [where] people decide they can do better by going home because they can't find work here, because they don't have legal documentation to allow them to work here."

Romney's proposal was widely mocked as impractical — and politically self-defeating. "He had a crazy policy of self-deportation, which was maniacal,” said Trump himself after Romney lost the election. “It sounded as bad as it was, and he lost all of the Latino vote. He lost the Asian vote. He lost everybody who is inspired to come into this country.”“The Democrats didn’t have a policy for dealing with illegal immigrants, but what they did have going for them is they weren’t mean-spirited about it,” Trump added. “They were kind."

Since then, however, Trump seems to have changed his mind. In March, the president sent an Oval Office message to migrants telling them to use CBP Home, a U.S. Customs and Border Protection app, to voluntarily leave the country — or else.

Otherwise, "they will be found, they will be deported, and they will never be admitted again to the United States," Trump said, calling self-deportation "the safest option for illegal aliens."

In April, the Trump administration added new fines to the equation: $998 per day for overstaying your final order of removal and up to $5,000 for failing to self-deport after saying you would. It also took steps to cut migrants off from crucial financial services such as bank accounts and credit cards.

Yet only a few thousand people decided to deport themselves — so on Monday the White House decided to sweeten its pitch with a $1,000 stipend and a free flight home (plus the promise of "preserv[ing] the option... to re-enter the United States legally in the future").

"We’re going to give them a stipend, we’re going to give them some money and a plane ticket, and then we’re going to work with them, if they’re good, if we want them back in, we’re going to work with them to get them back in as quickly as we can,” Trump said before the policy was officially announced.

Right now, migrants who leave the U.S. without legal status may have to wait up to 10 years before attempting to return.

How many people have been affected: As of April 1, about 5,000 people had used CBP Home to self-deport. The Department of Homeland Security said Monday that one migrant "recently utilized the [new stipend] program to receive a ticket for a flight from Chicago to Honduras" and that "additional tickets have already been booked for this week and the following week."

One real-life example: NPR recently reported on a Maryland woman named Mari who has been clashing with her husband over self-deportation. The husband, a roofer, wants to secure passports for their U.S.-born children and return to Guatemala if the situation devolves. But Mari, who fears they'll be targeted by gangs, wants to stay.

"My children were born here," Mari told NPR. "My daughters are going to school."

Mari added that her youngest daughter, age 6, has been suffering panic attacks because of Trump's immigration crackdown — and her parents' arguments.

"She's been crying at school," Mari said. "Having very bad stomachaches. A social worker had to step in."

"I was just feeling sad," Mari's daughter told NPR. "Mom told me it would be OK. I worry something will happen to her, like something will get her. Immigration is taking persons to their state where they grew up. My mom is from Guatemala. We are from here."

Removing ‘alien enemies’

What’s changed under Trump: On March 14, Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, only the fourth time in U.S. history it had be done — and the first time since World War II. The Revolutionary Era law allows the government to detain and expel immigrants age 14 or older without a court hearing — but only if they’re “alien enemies” from a country that’s invading or warring with the U.S.

So who are we at war with? According to Trump’s recent executive orders, any illegal crossings at the U.S.-Mexico border now constitute an “invasion,” and any members of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang, now qualify as alien enemies because they “have unlawfully infiltrated the United States and are conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the United States.”

Experts have disputed Trump’s interpretation of the law. Regardless, the administration defied a federal judge’s order and suddenly flew more than 200 Venezuelan migrants to a notorious El Salvadoran prison on March 15. (Noncitizens are almost never deported to a country other than their own.) Ever since, the president has been tussling over his actions with various courts — including the Supreme Court, which ruled on April 7 that anyone subject to the Alien Enemies Act must be given notice and a reasonable amount of time to challenge their removal in a “proper venue.”

In the meantime, Trump administration officials have ordered law enforcement nationwide to pursue suspected gang members into their homes, according to a copy of the directive obtained by USA Today — in some cases without any sort of warrant.

How many people have been affected: Hundreds, including Abrego Garcia.

One real-life example: Last August, Andry José Hernández Romero — a 31-year-old gay makeup artist from the central Venezuelan town of Capacho — arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in San Diego, according to the New Yorker.

Hernández Romero had traversed the dangerous jungle between Colombia and Panama known as the Darien Gap and scheduled an appointment through a U.S. government app. His goal was to claim asylum. In Capacho, he had often been followed and harassed by armed vigilantes aligned with Venezuela’s authoritarian regime.

Hernández Romero passed his initial screening, demonstrating a “credible fear” of persecution — but officials also found crown tattoos (one for “Mom,” one for “Dad”) on each of his wrists.

“The crown has been found to be an identifier for a Tren de Aragua gang member,” they said.

So instead of being released with a future court date like other asylum seekers who passed their screenings, Hernández Romero was detained — for months. A lawyer ultimately scheduled a court appearance in San Diego on March 13, but a few days before Hernández Romero was supposed to appear, ICE transferred him to South Texas. He missed his hearing as a result. The following day, Hernández Romero called his mother and said he was about to be transferred again. An ICE lawyer later told a judge that he had been “removed to El Salvador.”

“How can he be removed to El Salvador,” the judge asked, “if there’s no removal order?”

No one has heard from Hernández Romero since. He has no criminal record; family members and friends insist he is the furthest thing from a gang member. Experts, meanwhile, told the New Yorker that “Tren de Aragua does not use any tattoos as a form of gang identification.” Hernández Romero’s crown tattoos, they added, likely refer to Capacho’s Three Kings Day festival — a theatrical production to which he contributed as an actor, costume designer and makeup stylist.

Revoking parole and temporary protected status

What’s changed under Trump: Between October 2022 and January 2023 — as migrants fleeing humanitarian crises surged to the southern border — then-President Joe Biden created a sponsorship program designed to discourage illegal crossings by providing a legal way to enter the U.S. instead.

Under an existing immigration law known as humanitarian parole, migrants from Venezuela, Cuba, Haiti and Nicaragua would be eligible to live and work here legally for two years if U.S. residents agreed to financially sponsor them.

Hundreds of thousands of these migrants were eventually granted parole. Then, in October 2024, the Biden administration announced that it would not be extending their legal status and urged them to try to obtain legal status through other immigration programs (such as asylum) if they wished to stay.

But on March 25 of this year, the Trump administration went a step further, saying it would actually revoke migrants’ work permits and deportation protections starting in late April — at which point they would have to self-deport or face arrest and removal.

Around the same time, the Trump administration announced that it would also be revoking “temporary protected status” (TPS) for hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans as well, claiming that the threat of Tren de Aragua justified the move. (TPS shields foreign nationals who already live in the U.S. from being sent back to unsafe countries; under Biden, it had been extended to 2026 for Venezuelans who qualified.)

Yet so far, the courts have stymied Trump’s efforts. In March a federal judge in San Francisco ruled “there is no evidence that Venezuelan TPS holders are members of the TdA gang, have connections to the gang, and/or commit crimes.” In fact, the judge continued, “Venezuelan TPS holders have lower rates of criminality than the general population” and “generalization of criminality to the Venezuelan TPS population as a whole is baseless and smacks of racism predicated on generalized false stereotypes.”

A few weeks later, a federal judge in Boston blocked Trump’s plan to terminate parole, writing that “without any case-by-case justification,” it “undermines the rule of law” to revoke the legal status of “noncitizens who have complied with DHS programs and entered the country lawfully.”

How many people could be affected: Up to 532,000 migrants who were granted parole; roughly 600,000 Venezeulans with temporary protected status.

One real-life example: Two years ago, “Nickey,” 21, came to the U.S. from Haiti — a country wracked by gang violence — under the humanitarian parole program, according to radio station WBUR.

Without parole "I would probably not be where I am right now," Nickey told the Boston news outlet. "I could have been dead. But here I had the opportunity to grow — away from all this turmoil. I would say it's a chance in a lifetime."

Sponsored by an uncle, she’s now “in her second year of community college, works three jobs and serves as a student trustee on the board at her school,” according to WBUR.

But in March, Nickey was informed that her parole would now be expiring in April rather than August — meaning she will either have to leave the U.S., face deportation or secure new legal status.

She applied for asylum and is waiting to hear whether her application can proceed.

“That's the only option that I have because I can't go back to Haiti,” she told WBUR. “Going back to my country right now is just death for me.”

Revoking CBP One permits

What’s changed under Trump: CBP One, an earlier version of CBP Home, debuted during Trump’s first term; back then, it mainly helped visitors extend their short-term visas.

But starting in January 2023, the Biden administration expanded CBP One to allow migrants to book appointments at the U.S.-Mexico border. The idea was they could then plead for legal entry instead of attempting to cross illegally.

The program proved popular, with an average of 280,000 people competing for 1,450 appointment slots each day by the end of 2024. Ultimately, nearly a million people entered the U.S. (with two-year work permits) through CBP One.

Trump suspended CBP One for new arrivals his first day back in office, but people already in the U.S. believed they could stay at least until their permits expired.

Last month, however, many of those same people suddenly started to receive cancellation notices via email. “It is time for you to leave the United States,” the messages began. Some told recipients to leave immediately; others gave them seven days.

In a statement to the Associated Press, Customs and Border Protection confirmed that it had started to terminate temporary legal status under CBP One.

How many people could be affected: Up to 936,000

One real-life example: Maria, a 48-year-old Nicaraguan woman, came to Florida via CBP One. She cheered Trump’s election, according to AP. But she recently received a notice telling her to leave — news that landed like “a bomb.”

“It paralyzed me,” she said.

CBP One recipients have a one-year window to file an asylum claim or seek other relief. Maria — who gave only her middle name for fear of being detained and deported — told the AP that she would file for asylum while she continued to support herself by cleaning houses.

Others, however, have already left the U.S., according to AP.

“It’s really confusing,” Robyn Barnard, senior director for refugee advocacy at Human Rights First, told the outlet. “Imagine how people who entered through that process feel when they’re hearing through their different community chats, rumors or screenshots that some friends have received notice and others didn’t.”

Terminating student visas/revoking student green cards

What’s changed under Trump: During the 2023-24 school year, there were more than 1.1 million international students in the United States, according to a recent report. Together, they pumped nearly $44 billion into the U.S. economy, generating 378,000 jobs.

The Trump administration has tried to shrink America’s international student population in two ways. First, Secretary of State Marco Rubio invoked an obscure provision earlier this year to cancel the student visas of hundreds of noncitizens whose pro-Palestinian activism, in his view, was creating “serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.”

“We are not going to be importing activists,” Rubio said. “They’re here to study. They’re here to go to class. They’re not here to lead activist movements that are disruptive and undermine the — our universities. I think it’s lunacy to continue to allow that.”

(At least two permanent legal residents — Mahmoud Khalil and Mohsen Madawi, pro-Palestinian activists at Columbia University — are also fighting deportation after the State Department moved to revoke their green cards and arrested them in March and April.)

Then came a much larger wave of visa cancellations — one that seemed harder to explain. “In some cases, students had minor traffic violations or other infractions,” the New York Times reported. “But in other cases, there appeared to be no obvious cause for the revocations.”

After students learned that their records had been deleted from the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System — a move that stoked panic on campuses nationwide and led some to leave the country — more than 100 lawsuits were filed, according to Politico. In roughly half of those cases — spanning at least 23 states — judges ordered the administration to temporarily undo its actions, declaring them unlawful.

In response, the White House reversed course last Friday, restoring the records it had purged while immigration officials began work on a new system for reviewing and terminating student visas.

A senior Department of Homeland Security official told the New York Times that “students whose legal status was restored on Friday could still very well have it terminated in the future, along with their visas.”

How many people have been affected: 1,500

One real-life example: Earlier this month, a lawsuit was filed in New Hampshire on behalf of several foreign students who had their F-1 status revoked with no explanation or due process.

According to their lawyers, all of these noncitizens “maintained their student status by making progress toward completing their course of study,” and none engaged “in unauthorized employment” or had “any conviction for a crime of violence for which a sentence of more than one year imprisonment may be imposed.”

“The only criminal matters the individual Plaintiffs have encountered are either dismissed non-violent misdemeanor charges or driving without a valid U.S. driver’s license (but using an international or foreign driver’s license),” the lawsuit continued.

Yet suddenly losing their status would lead to “severe financial and academic hardship,” according to the complaint.

“Plaintiff Linkhith Babu Gorrela’s graduation date for his Master’s program is May 20, 2025. Without a valid F-1 student status, he may not obtain his Master’s degree. Nor can he participate in the OPT program after graduation,” the document reads. “Plaintiff Hangrui Zhang’s only source of income is his research assistantship, which has been cut off in light of the termination of his F-1 student status. Plaintiff Haoyang An will have to abandon his Master’s program despite having already invested $329,196 in his education in the United States. Similarly, Plaintiff Thanuj Kumar Gummadavelli and Plaintiff Manikanta Pasula have only one semester left before they can complete their Master’s degrees and participate in the OPT program. Their graduation is unpredictable and unlikely unless this Court intervenes.”

Cracking down on permanent U.S. residents (green card holders) for old, minor offenses

What’s changed under Trump: About 13 million noncitizens currently have permanent legal status (i.e., possess a green card). About 9 million of them are eligible to become citizens because they’ve been permanent residents for at least five years, or because they’ve been married to a citizen for at least three years.

Not all green card holders pursue citizenship; the application is expensive and the process is bureaucratic. But usually they’re not targeted for deportation unless they commit serious crimes.

Under Trump, however, federal agents have shifted into maximum enforcement mode in order to fulfill the president’s goal of mass deportation — and they have been “detaining permanent U.S. residents convicted of years-old minor offenses and moving to deport them,” according to the New York Times.

How many people have been affected: Unclear

One real-life example: Erlin Richards, 43, has had a green card since 1992. He works as an electrician in the New York metro area; according to his lawyer, who spoke to the New York Times, Richards has never spent a day behind bars.

Yet now Richards — a native of the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent with three U.S.-born children — is stuck in an immigration detention facility in Elizabeth, N.J. Why? Because in 2006 — nearly two decades ago — he was convicted in Texas for marijuana possession.

After paying a fine, Richards thought he’d put the incident behind him. He traveled to Canada and his home country without any problems. But last month, upon returning to JFK Airport from a vacation in the Dominican Republic, he was locked up.

“Haven’t you been watching the news?” Richards recalled being told. “Trump is president now. We have to detain you.”

Ironically, Richards is now being held “for carrying a substance that is legal in many states, including his home state of New York,” his lawyer told the Times.

Detaining and deporting tourists

What’s changed under Trump: The law remains the same — if you come from a country (mostly in Europe and Asia) whose citizens are allowed to enter the U.S. with a 90-day tourist permit instead of a visa, you’re not allowed to work while you’re here.

But enforcement of this rule seems to have ramped up dramatically since Trump took office, leading to multiple incidents in which tourists suspected of breaking it have been stopped at U.S. border crossings and detained for weeks before being forced to fly home at their own expense.

Partially as a result, the number of overseas visitors to the U.S. fell by 11.6% in March compared to the previous year — including a 17.2% drop in people traveling from western Europe.

How many people have been affected: According to the Associated Press, “U.S. authorities did not respond to a request … for figures on how many tourists have recently been held at detention facilities or explain why they weren’t simply denied entry.”

One real-life example: On March 18, Charlotte Pohl, 19, and Maria Lepère, 18 — both German citizens — arrived in Honolulu on a flight from New Zealand. They were celebrating their high-school graduation with an around-the-world backpacking trip.

The plan was to stay in Hawaii for five weeks before proceeding to California and Costa Rica. But Customs and Border Protection officials thought it was suspicious that Pohl and Lepère had only booked accommodations (an Airbnb) for the first two nights of their stay — and things soon escalated when they admitted they occasionally did “small freelance jobs online” for non-U.S. clients.

“Both claimed they were touring California but later admitted they intended to work — something strictly prohibited under U.S. immigration laws for these visas,” CBP officials told the New York Post.

Ultimately, Pohl and Lepère were denied entry and detained overnight — then handcuffed, escorted to the airport and put on a flight back to Germany.

But they have subsequently described an experience that made them feel “small and powerless” — and claimed their words were “twisted.”

The transcript “contained sentences we didn’t actually say,” Pohl told the German outlet Ostsee Zeitung. “They twisted it to make it seem as if we admitted that we wanted to work illegally in the U.S.”

As a result, “they made us do a full strip search,” one of the teens elaborated in a now deleted Reddit post. “It was really cold. We had to undress completely, including bra and underwear, and even had to squat and spread. … I don’t want to describe it in too much detail, but it was humiliating and scary.”

A dinner consisting of “two slices of toast and expired cheese” and a night in a cell with convicted criminals and a moldy mattress followed.

“We wanted to travel spontaneously, just like we had done in Thailand and New Zealand,” Pohl told Ostsee Zeitung, explaining why they hadn’t fully booked accommodations in advance.

But what they wound up experiencing, Lepère added, was “like a fever dream.”

Targeting ‘homegrown criminals’

What’s changed under Trump: Nothing yet. But Trump has repeatedly signaled his interest in sending U.S. citizens to prisons in other countries — most recently in conversation with El Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, who is currently accepting “alien enemies” into a notoriously brutal prison there.

“We always have to obey the laws, but we also have homegrown criminals that push people into subways, that hit elderly ladies on the back of the head with a baseball bat when they’re not looking, that are absolute monsters,” Trump told reporters earlier this month. “I’d like to include them.”

He added that Attorney General Pam Bondi is "studying the law.”

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt previously confirmed that Trump is interested in deporting "heinous, violent criminals" who are U.S. citizens to El Salvador "if there's a legal pathway to do that." She did not clarify whether he is referring only to naturalized citizens or to any citizen who commits a crime.

Trump is already engaged in “extrajudicial imprisonment by foreign proxy," as David Bier, an immigration expert at the libertarian Cato Institute, put it to NBC News — i.e., the deeply unusual practice of deporting accused gang members without due process to a country where they’ve never lived.

But "U.S. citizens may not be deported to imprisonment abroad,” Bier explained. “There is no authority for that in any U.S. law.”

|

https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/immigration-u-declines-first-time-100000433.html

Immigration to U.S. declines for first time in 50 years amid Trump crackdown, study shows

For the first time in more than half a century, immigrants leaving the U.S. outnumber those arriving, a phenomenon that may signal President Trump's historic mass deportation efforts are having the intended effect.

An analysis of census data released by Pew Research Center on Thursday noted that between January and June, the United States' foreign-born population had declined by more than a million people.

Millions of people arrived at the border between 2021 and 2023 seeking refuge in America after the COVID-19 pandemic emergency, which ravaged many of their home countries. In 2023, California was home to 11.3 million immigrants, roughly 28.4% of the national total, according to Pew.

In January, 53.3 million immigrants lived in the U.S., the highest number recorded, but in the months that followed, those who left or were deported surpassed those arriving — the first drop since the 1960s. As of June, the number living in the U.S. had dropped to 51.9 million. Pew did not calculate how many immigrants are undocumented.

Trump and his supporters have applauded the exodus, with the president declaring "Promises Made. Promises Kept," in a social media post this month.

"Seven months into his second term, it’s clear that the president has done what he said he'd do by reestablishing law and order at our southern border and by removing violent illegal immigrants from our nation," Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem wrote in a USA Today column on Thursday. "Both actions were necessary for Americans' peace and prosperity."

But some experts caution that such declines will have negative economic effects on the United States if they continue, resulting in labor shortages as America's birth rate continues to drop.

"Looking ahead in the future, we're going to have to rely on immigrant workers to fulfill a lot of the jobs in this country," said Victor Narro, project director at UCLA Labor Center. "Like it or not, the demographics are going to be changing in this country. It's already changing, but it's going to be more pronounced in the future, especially with the decline in native-born workers."

The Pew analysis highlights several policy changes that have affected the number of immigrants in the country, beginning during then-President Biden's term.

In June 2024, Biden signed a proclamation that bars migrants from seeking asylum along the U.S. border with Mexico at times when crossings are high, a change that was designed to make it harder for those who enter the country without prior authorization.

Trump, who campaigned on hard-line immigration policies, signed an executive order on the first day of his second term, declaring an "invasion" at the southern border. The move severely restricted entry into the country by barring people who arrive between ports of entry from seeking asylum or invoking other protections that would allow them to temporarily remain in the U.S.Widespread immigration enforcement operations across Southern California began in June, prompting pushback from advocates and local leaders. The federal government responded by deploying thousands of Marines and National Guard troops to L.A. after the raids sparked scattered protests.

Homeland Security agents have arrested 4,481 undocumented immigrants in the Los Angeles area since June 6, the agency said this month.

Narro said the decrease in immigrants outlined in the study may not be as severe as the numbers suggest because of a reduction in response rates amid heightened enforcement.

"When you have the climate that you have today with fear of deportation, being arrested or detained by ICE — all the stuff that's coming out of the Trump administration — people are going to be less willing to participate in the survey and documentation that goes into these reports," Narro said.

Michael Capuano, research director at Federation for American Immigration Reform, a nonprofit that advocates for a reduction in immigration, said the numbers are trending in the right direction.

"We see it as a positive start," Capuano said. "Obviously enforcement at the border is now working. The population is beginning to decrease. We'd like to see that trend continue because, ultimately, we think the policy of the last four years has been proven to be unsustainable."

Capuano disagrees that the decrease in immigrants will cause problems for the country's workforce.

"We don't believe that ultimately there's going to be this huge disruption," he said. "There is no field that Americans won't work in. Pew notes in its own study that American-born workers are the majority in every job field."

In 2023, the last year with complete data, 33 million immigrants were part of the country's workforce, including about 10 million undocumented individuals. Roughly 19% of workers were immigrants in 2023, up from 15% two decades earlier, according to Pew.

"Immigrants are a huge part of American society," said Toby Higbie, a professor of history and labor studies at UCLA. "Those who are running the federal government right now imagine that they can remove all immigrants from this society, but it's just not going to happen. It's not going to happen because the children of immigrants will fight against it and because our country needs immigrant workers to make the economy work."

The United States experienced a negative net immigration in the 1930s during the Great Depression when at least 400,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans left the country, often as a result of government pressure and repatriation programs. Not long after, the U.S. implemented the bracero program in 1942 in which the U.S. allowed millions of Mexican citizens to work in the country to address labor shortages during World War II.

Higbie predicts the decline in immigration won't last long, particularly if prices on goods rise amid labor shortages.

"You could say that there's a cycle here where we invite immigrants to work in our economy, and then there's a political reaction by some in our country, and they kick them out, and then we invite them back," he said. "I suspect that the Trump administration, after going through this process of brutally deporting people, will turn around and propose a guest worker program in order to maintain a docile immigrant workforce."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

No comments:

Post a Comment