In August, I finally got around to posting ESPN's 100 greatest Baseball players with rankings that I did not entirely agree with.

These articles explain why and describe the difficulty in assessing Charleston's case.

Thanks for tuning in.

Top 100 MLB players of all time: What if Oscar Charleston is the best baseball player of all time -- and why it's so important to try to find out

Could Oscar Charleston be the best player of all time?

The question is a big one, perfectly straightforward and ultimately, not even the real subject of this story. For now, just keep an open mind and take this as a jumping off point: it's a reasonable one to ask.

Bill James once wrote, when comparing Charleston to legendary center fielders Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio and Willie Mays, "Oscar Charleston probably rates right with them. Some say he was better. It's hard to imagine how anyone could have been better, but Charleston, in a sense, put Mays and Mantle together."

Charleston hasn't been completely overlooked. He is after all a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame, having been inducted in 1976, 22 years after his death. Yet, like so many other greats from the Negro Leagues of Charleston's time, he fell so far off the historical radar that the first comprehensive biography about him, written by Dr. Jeremy Beer, was not published until 2019. Fittingly, Beer chose the title, "Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball's Greatest Forgotten Star."

In his biography, Beer notes that when Charleston died at 57, his passing merited scant notice in the mainstream press.

"No one was yet going around asking former Negro Leagues players about their lives and careers," Beer said in an email exchange. "So, we don't have him on the record much himself, and most of the guys who ended up getting interviewed in the 1980s and later only knew him from his later playing career, at best."

This week, when ESPN is ranking the top 100 players ever, putting Black stars from Charleston's era into their proper context remains a difficult proposition.

Records from the time are scattered and incomplete, though dedicated researchers are trying to change that. It's not just statistics that are unearthed. So, too, are the stories of many of these players, whose legacies were lost, forgotten, misunderstood, ignored or dismissed.

The effort to recover these histories is something like an excavation. Anecdotes have been found, oral histories have been recorded and stories have been passed down through generations. And, almost as essential, numerous box scores have been unearthed.

"Hopefully the work that we do, and the work that is being done to pull these statistics together, and the fact that Major League Baseball has formally recognized [the numbers] will start to change some mindsets," said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

That work is why we can still consider the body of work of a player like Charleston, who was born in 1896, started playing ball for a living in 1915 and died in 1954.

"When I heard Buck [O'Neil] talk about him, along with some of the other old timers ... they'd say the closest thing to Oscar Charleston was Willie Mays, that's just downright frightening," Kendrick said. "It's just hard to believe that a player was that great and we really don't know who he is."

Take this quote: "In my opinion, the greatest ballplayer I've ever seen was Oscar Charleston. When I say this, I'm not overlooking Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig and all of them."

That's from 1953, 12 years after Charleston stopped playing full time, and was uttered by a player, manager and scout named Bennie Borgmann.

And he's not the only one. In the seminal "The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract" from 2003, James ranked Charleston fourth on his list of greatest players of all time -- citing a number of others who made the same claim as Borgmann, that Charleston was the best player they ever saw.

The list included Hall of Fame manager John McGraw, who said, "If Oscar Charleston isn't the greatest baseball player in world, then I'm no judge of baseball talent." (And he said this in 1922, after Babe Ruth had already become perhaps the most famous person in America.)

In addition to everything else, O'Neil was one of baseball's greatest scouts. James quoted O'Neil as saying, "Charlie was a tremendous left-handed hitter who could also bunt, steal a hundred bases a year and cover center field as well as anyone before him or since. ... He was like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth and Tris Speaker rolled into one."

Finally, Grantland Rice reportedly once wrote a column, in which he claimed, "It's impossible for anybody to be a better ballplayer than Oscar Charleston."

Despite all of this, James also noted that among top 100 lists that had been put together by the time of the 2003 Abstract, only one had Charleston on the list, and that was by The Sporting News, which ranked him No. 67 in 1998.

"I don't blame anyone for not including Oscar," Beer said. "Until recently it has been really hard to evaluate him, and it still is to a significant extent. But if you dig carefully into his numbers, his legacy, what people said about him, then I think it's hard not to come to the same conclusion to which Bill James came 20 years ago: that he deserves to be in the discussion."

As great as Charleston was, through time and neglect, his exploits had lost their proper context, and he was far from alone.

"Keep in mind that we have forgotten just about all Negro Leaguers from the generations that preceded [Satchel] Paige and [Josh] Gibson," Beer said. "So in part Oscar is simply caught up in that cultural amnesia. He stands for the larger problem."

The problem is inscrutable, but not unsurmountable: how to revive the legacies of some of the best players in baseball history, to make them known to all fans, not just a lucky few.

The scattered numbers of the Negro Leagues have been around for decades, but were considered by some to be unreliable, incomplete and, basically, useless. Yet those numbers were often used to tell their story.

"We've been here all along telling you, 'No, it did happen and it happened in grandiose fashion,'" Kendrick said. "This is that wonderful game of comparisons and statistics. The comparisons have always been there. The statistics, however, have not been there in a way where people would give them a real credence that they should."

Perhaps now that is changing. In December 2020, MLB announced that it would be adding the Negro Leagues to the official statistical record. In doing so, it was acknowledging the "major league" status of a number of Black leagues from the pre-integration era. As many pointed out, the reality is that the leagues were major all along, even in the face of numerous inequities that resulted in lesser coverage, poorer record keeping, worse playing conditions and so much else.

"No major leaguer ever had to deal with the set of social circumstances that the Negro Leagues players had to deal with," Kendrick said. "They had to play not knowing where you can get something to eat, sleep on the bus, can't wash your uniforms. No major league athlete ever had to endure that."

There are conflicting views of what MLB's decision to "promote" the Negro Leagues means, and I urge you to read Howard Bryant's powerful essay on the subject that was published at the time of the announcement. Here, we are merely looking into the question of what we should do with those statistics -- an enormous collaborative effort by researchers, which gradually built up the definitive Negro Leagues database at Seamheads.com -- now that they are a part of the official major league record. Around the same time, the data was fully incorporated into the pages of Baseball Reference, brought into the mainstream for the first time.

Let's consider a simple leaderboard generated by Baseball Reference's Stathead utility. It's the all-time top 10 in lifetime OPS+ for all players in the database with at least 2,500 recorded plate appearances during the modern era.

1. Josh Gibson (215)

2. Babe Ruth (206)

3. Ted Williams (191)

4. Oscar Charleston (184)

5. Barry Bonds (182)

6. Buck Leonard (181)

7. Lou Gehrig (179)

8. Turkey Stearnes (177)

9. Mike Trout (176)

10. Rogers Hornsby (175)

There are four Negro Leagues legends on this list, all of whom are in the Baseball Hall of Fame. (While OPS+ is normally calibrated for league and ballpark context, the work to calculate good park factors for the Negro Leagues is still a work in progress. Baseball Reference has yet to add them for the Negro Leagues data, and the effort to more accurately calculate another building block of WAR -- replacement level -- is also ongoing.)

|

| Satchel Paige didn't get a chance to play in MLB until the end of his career, while Josh Gibson never got a chance at all. Mark Rucker/Transcendental Graphics, Getty Images |

There is no consensus on whether we should accept these numbers at face value, or if they should simply fuel a broader discussion.

Still, if we want the numbers to expand our ability to put overlooked Negro Leagues greats into their proper context, we need to have a working understanding of how to interpret them.

As part of the rollout of its enhanced Negro Leagues presence on Baseball Reference, Sports Reference collected a number of essays on the subject, statistical and otherwise. The work was also collected in a book edited by company founder Sean Forman and writer Cecilia Tan titled "The Negro Leagues are Major Leagues: Essays and Research for Overdue Recognition". In it is an essay by researcher and analyst Todd Peterson with a title that gives away its conclusion: "Negro Leagues = Major Leagues".

The numbers, Peterson concludes, should be treated legitimately. The conclusion is at the end of a long road of research. Peterson edited a collection a few years ago on these topics which contain a longer version of his essay than is what is at Baseball Reference. In fact, the document he sent me is 45 pages long.

Peterson's standpoint is clear: "I militantly fall into the camp of taking the pre-integration NLB data at face value," he said. There were a couple of key points that led Peterson to his conclusions. One is the success Black teams had in head-to-head competition against teams from white leagues, some of which were actual teams (like the 1917 New York Giants) and many of which were All-Star teams. So far, Peterson has been able to document that Black teams from 1900 to 1948 went 316-283-21 against white teams (.527 winning percentage). That scales up accordingly when you look at the success of Black teams against other levels of competition. That is really only the tip of the iceberg of Peterson's research, but it's a compelling one.

In many cases, this effect trickles down to the player level in documented games between Black and white teams. Charleston's page at Seamheads sums up 37 games against all-white major league competition. He hit .355 in those games, homered 10 times, slugged .738 and drove in 38 runs.

There have been numerous attempts at creating MLEs out of Negro Leagues statistics. This is similar to the way that analysts will adjust current minor league numbers to suggest what they would look like in a major league context, to help guide prospect analysis, for instance.

One of the most cited systems for Negro Leagues MLEs was created by analyst and researcher Eric Chalek. The process is complex, as there is a lot to account for -- not all of the Negro Leagues were of the same quality. The quality of playing venues was wildly disparate and the prevalence of ballparks with extreme dimensions was much greater than in the AL or NL.

"Stars Park in St. Louis had a [trolley car] barn that provided the boundary and outfield wall in its left field," Chalek said. "The barn was so close to home plate that if you viewed the park from the air, its playing surface resembled a rectangle more than a diamond."

Also, the spread of talent in most Negro Leagues is considered larger than it was in the AL or NL, at least beyond the 1900s. Black leagues were drawing from a much smaller percentage of the population and there were numerous challenges for maintaining stable rosters and schedules, leading to similar competitive balance issues to what the AL and NL faced in the first decade of the 20th century.

As an example, consider the 1943 Homestead Grays. That season, Gibson hit .466, which in the revamped Baseball Reference leaderboard now ranks second all time, behind Tetelo Vargas -- from the same league in the same season. The Grays were loaded with talent, no doubt, with Gibson joined by fellow Hall of Famers Buck Leonard, Jud Wilson, Cool Papa Bell and Ray Brown.

Still, just as it was for AL and NL teams, 1943 was a war year and a lot of ballplayers were serving in the military. The Grays went 53-14-1 in a league in which teams played a range of documented games numbering between 16 and 68. Sample size is an issue when it comes to assessing Negro Leagues single-season numbers, because of the actual length of the seasons, and the fact that we don't have documentation for nearly all of the games.

However, the overriding factor for AL, NL and Negro Leagues teams is that none of them were playing against the best possible competition. Major league teams pursued star-level players, but the overall presence of Black players on most rosters was limited for a long time after integration.

"I have recently seen some [major league equivalencies, or MLEs] that put the Negro Leagues at .8 of major league value [basically Triple-A levels]," Peterson said. "However, if all things had been equal, I believe about 33% of [major league] and [Negro Leagues] players would not have been playing in their respective leagues. Therefore, both organizations' totals are similarly inflated and should be contextualized equally."

That's based on current participation levels of non-white players, which have settled into a rate between 30% to 40%, by Peterson's estimation. What it means is: A whole slew of players who were considered to be major leaguers before 1947 would not have been were baseball integrated all along.

All of this needs to be understood as we deploy the numbers that have been documented. It's amazing that Lefty O'Doul hit .383 in 1930, but we also have to understand that he did that in a season where the overall NL batting average was .303. We have always gone to that trouble for AL and NL greats and now we have to do the same for Negro Leaguers.

"It's better when we can corroborate stories with stats," Chalek said. "It's better yet when we can use the same analytical tools we use on MLB players to get closer to an accurate estimate of a Negro Leagues player's talent. These guys deserve more appreciation, and it's very hard to appreciate them fully without understanding them in a comparison to what we already know about greatness in baseball."

Once we do that, then we can really have a discussion.

"[The major leagues] from 1876 on had extremely organized recordkeeping. The Negro Leagues probably had at least half of the best players in the 1920s and 1930s, but not the same level of stadiums, attendance or recordkeeping," Bill James said, via email. "It's absolutely essential to respect the players for what they were. It is essential to respect the work that was done after the fact to recover and create a statistical record."

The ultimate data point on how we should regard pre-integration Black ballplayers is found in what happened after integration. The success of former Negro Leaguers, or those who would have played in the Negro Leagues in a previous era, was immediate, beginning with Jackie Robinson's rookie season. It was widespread. And it was dominant.

Peterson documents that former Negro Leaguers outperformed their counterparts in the years after Robinson broke the color line, and by a considerable margin, outhitting them .277 to .255 with an OPS edge of 111 points. This is a reflection of the contributions of the star-level players like Ernie Banks, Minnie Minoso, Robinson, Roy Campanella and so many others. It's also a reflection of the lack of a "middle class" of Black players after integration, as their presence on rosters was still being artificially suppressed.

Still, consider this tweet from Adam Darowski who works for Sports Reference. For almost three decades after integration, former Negro Leaguers won more than their share of Rookie of the Year and MVP awards, and they started winning those honors in the immediate aftermath of Robinson joining the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The post-integration leaderboards reflect the long-ignored reality that the best players in Black baseball were at the very least as good as the best in the all-white leagues. Knowing that serves us when we say something like, "Oscar Charleston batted .397 with a .700 slugging percentage between 1921 and 1925."

During those same seasons, Ruth hit .357 with a .728 slugging. Ruth was the best player in his league, perhaps the best ever. You can say the same things about Charleston. And if you say that Charleston wouldn't have put up those numbers in the AL or NL, that might be true. But it would also be true to suggest that Ruth wouldn't have put up the same career numbers if he had had to face a steady dose of Smokey Joe Williams, Satchel Paige and Bullet Rogan over his career.

"Oscar Charleston probably would not have batted .364 lifetime in an integrated league, if he would have been given a chance to do so," Peterson said. But "there is no way Ty Cobb is hitting .366 against the likes of John Donaldson, [Smokey] Joe Williams and Dick Redding, etc. The Babe, great as he was, is not mashing 714 homers, either."

|

| The Negro Leagues' best deserve to be in the debate for best baseball players of all time. Clarence Gatson/Gado/Getty Images |

Let's turn back to Beer and his book. Why did Beer write it? Because in 2003, he read Bill James' historical abstract. He saw that James had ranked Charleston No. 4 on his list of the best players in history. And he had no idea who Oscar Charleston was. When Beer found out that, like him, Charleston was from Indiana, the quest to find out more was on.

The number that got Beer started was a ranking -- 4 -- but it was still a number. And the number sent Beer down a rabbit hole that led to years of work and an award-winning book. That is why the numbers matter.

That really is at the crux of why, for me, it is imperative that we take advantage of the trove of data from the Negro Leagues era that is now available to us and easier to work with than ever. And it's why when we have these "greatest ever" discussions, we don't leave those numbers out of the analysis. Don't shrug your shoulders and say, "Those don't sound right." Because they are as right as they can be. They are a still-growing record of what these players actually did on the field at the highest level they were allowed to play.

The WAR figures at Baseball Reference are contextualized for the leagues and ballparks in which they are compiled, though the Negro Leagues data currently is not adjusted for ballparks, and WAR is hard to compare because the Negro Leagues seasons were shorter. However, under the hood of WAR methodology is a rate stat that can be deployed here: Individual winning percentage.

I downloaded the bWAR database and compiled a leaderboard based on career winning percentage. (I had to stick with position players, as pitchers work a little differently, so apologies to Satch, Smokey Joe, Bullet Rogan, Hilton Smith and the rest.) I calculated the career winning percentages for every player and converted the results into an index. So 100 is average, 110 is one standard deviation better than average, 120 is two standard deviations better than average and so on. These indexes are based only on the group of players who compiled at least 2,500 documented career plate appearances.

The actual numbers here aren't as important as the investigations they might lead to. When we see a number like 184 (Charleston's OPS+) or 140.8 (Stearnes' index) on an all-time leaderboard, those curious about baseball can't help but to want to know more. It might start them digging into the dustbins of the internet, where they might find a string of testimonials like those that were uttered about Charleston during his time and beyond. Thanks to the numbers, the stories stay alive.

"It is always important that we never forget those, as the late great Buck O'Neil always said, who 'built the bridge across the chasm of prejudice,'" Kendrick said. "Those that opened the door for Black and brown players to move into the major leagues and help change our game. It is incumbent upon this museum to make sure that they are never forgotten."

It's incumbent on us to do that, too. Is Oscar Charleston the best player who ever lived? I don't know. I'd still rank Ruth ahead of him and everyone else, despite Gibson's lofty standing here. What I do know is that Charleston is part of the conversation. Having that debate is the least we can do.

| Player |

|---|

| 1. Josh Gibson (158.4)* |

| 2. Babe Ruth (156.7)* |

| 3. Rogers Hornsby (150.0)* |

| 4. Mike Trout (148.2)# |

| 5. Barry Bonds (147.0) |

| 6. Ted Williams (146.1)* |

| 7. Oscar Charleston (144.7)* |

| 8. Willie Mays (141.3)* |

| 9. Lou Gehrig (141.1)* |

| 10. Turkey Stearnes (140.8)* |

| 11. Buck Leonard (139.9)* |

| 12. Mookie Betts (139.7)# |

| 13. Willie Wells (139.2)* |

| 14. Mickey Mantle (138.5)* |

| 15. Ty Cobb (137.6)* |

| 16. Dan Brouthers (137.2)* |

| 17. Honus Wagner (137.2)* |

| 18. Tris Speaker (135.8)* |

| 19. Joe DiMaggio (135.2)* |

| 20. Mike Schmidt (134.9)* |

| Minimum 2,500 plate appearances |

| * Hall of Famer |

| # active player |

Hothead: How the Oscar Charleston Myth Began

This article was written by Jeremy Beer

This article was published in Spring 2017 Baseball Research Journal

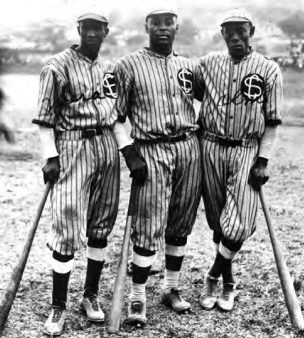

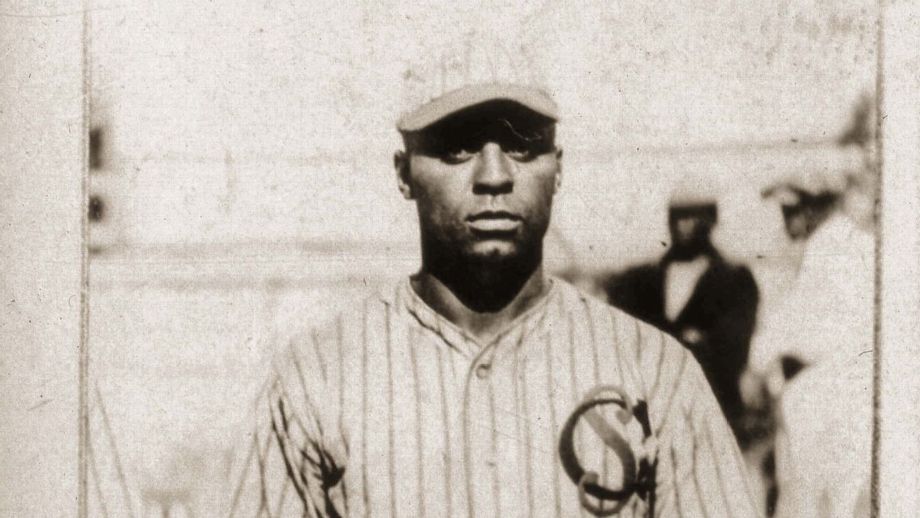

Oscar Charleston is shown here in the uniform of the Santa Clara Leopardos, circa 1923. The 1923-24 Leopardos, for whom Charleston played, were considered the best Cuban team in history—a team so dominant that halfway through the season the league simply declared them champions and then reorganized. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

April 11, 2015, marked the centenary of Oscar Charleston’s debut in American professional Black baseball. The event passed without fanfare. Even though Charleston was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1976, many of today’s devoted baseball fans do not recognize his name, and when Charleston is thought of at all, it is often as a talented but temperamental hothead. There are many reasons for Charleston’s neglect, including his early death and lack of descendants. One of the unfortunate consequences of this neglect has been the persistence of a false image of Charleston as a dangerous loose cannon, bordering on psychopathic. Charleston began to gain this reputation because of an event that occurred at the end of his rookie season. The story of how that happened is usually highly condensed and often mangled. It deserves to be told in full.

Ranked in 2001 by Bill James as the fourth-greatest player of all time, Charleston may have been the most respected man in Black baseball in the years before Jackie Robinson signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers.1 As James pointed out, Charleston is “regarded by many knowledgeable people as the greatest baseball player who ever lived.”2 One of those people was a longtime Cardinals scout named Bennie Borgmann. Soon after former Negro Leagues catcher Quincy Trouppe started scouting for the Cardinals in 1953, Borgan told him, “Quincy, in my opinion, the greatest ball player I’ve ever seen was Oscar Charleston. When I say this, I’m not overlooking Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, and all of them.”3

Buck O’Neil claimed that Charleston was even better than Willie Mays, whom O’Neil regarded as the greatest major leaguer he had ever seen. O’Neil described Oscar as “like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker rolled into one.”4 In a poll of twenty-four Negro League historians conducted around the turn of the millennium, Charleston received more votes for greatest player in Negro Leagues history than anyone else.5 While the data are incomplete, Gary Ashwill’s sabermetrically-oriented Seamheads.com currently estimates that Charleston compiled more Win Shares than any other player in Black baseball history.6 Charleston even played a role in the game’s integration. He was one of the first Black scouts for a major league team when Branch Rickey began using him to evaluate Negro League players for the Dodgers. The Dodgers only signed future Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella because of Charleston’s advice.7 In the face of this, Charleston’s obscurity seems highly unjustified.

Mark Ribowsky, among others, has given us the image of Charleston as a barely human berserker. “With his scowl and brawling tendencies, Charleston was a baleful man, and he enjoyed watching people gulp when he got mad,” wrote Ribowsky in his not entirely reliable history of the Negro leagues.8 Charleston was an “autocrat,” he claimed, a man with a “thuggish reputation” who was “barbaric on the basepaths.”9 He was “a great big snarling bear of a man with glaring eyes and a temper that periodically drove him beyond the edge of sanity.” Oscar may have “compiled a long record of achievement on the field,” but he also had “a police record almost as long.”10

Those who have dug into the sources know that such a portrait is wildly distorted. No contemporary sportswriter or anyone who knew Charleston personally ever called him a thug, and Charleston emphatically did not have a substantial police record. While he was happy to join fights in progress, he infrequently started them. And although as a young man, especially, he had a quick temper, he was not, to use Ribowsky’s adjective, “barbaric.”

Then, too, context matters. In both Black baseball and the majors, violence was vastly more common during the first decades of the twentieth century than it is today. Ballplayers almost routinely got into fights with opposing ballplayers, with their own teammates, with coaches and managers, with umpires, and with fans. As Charles Leerhsen demonstrates at length in his new, judicious biography of Ty Cobb, it was a time in which fighting and violence were integral to the game—and, arguably, American society as a whole. “The drama critic George Jean Nathan, an avid baseball fan, counted 355 physical assaults on umpires by players and fans during the 1909 season alone.”11

Oscar Charleston, in fact, was characteristically self-disciplined and reasonably good-humored, not to mention significantly more intellectual than most of his ballplayer peers, Black or White. Numerous extant photos show him smiling. Accounts do not dispute that Charleston was exceptionally tough, and we know he had a passion for boxing.12 But John Schulian, who spoke to a number of ex-teammates and relations for his splendid Sports Illustrated essay on Charleston, told me that “you get the feeling…that here is this rough ballplayer who would fight anybody, crash into anything, take out fielders, but was a real puppy dog.”13 Rodney Redman, whose father knew Charleston well, and who himself was close to Charleston’s brother Shedrick, said that he never heard anything negative about Oscar: “My father only said good things about him.” Mamie Johnson, who played for Oscar on the 1954 Indianapolis Clowns, said, “What I would say is that he was a beautiful person.” Did she enjoy playing for him? “Oh yes, he was great.” James Robinson, who played for Oscar on the 1952 Philadelphia Stars, remembers him as “mild” and “friendly.” Clifford Layton, another member of the 1954 Clowns, recalls Charleston as “a very intelligent man” whose “personality was beautiful.”14

In short, Charleston was certainly not a dark-souled, frightful hooligan. So how has this image taken hold?

EARLY LIFE AND ARMY BASEBALL OVERSEAS

Oscar McKinley Charleston was born in Indianapolis on October 14, 1896. Tom and Mary Charleston, along with three sons, had likely arrived earlier that year, migrating to Indiana by way of Nashville.15 The Charlestons moved frequently—living in at least ten different homes while Oscar was a child, mostly on the north side of the vibrant, African American Indiana Avenue neighborhood—and they were a spirited lot.16 Mary was once hauled into court for greeting a deputy with an ax. Brothers Roy, Berl, and Casper each had multiple run-ins with the law.17 Roy eventually channeled his thymos well enough to become a locally prominent boxer.18

Oscar finished the eighth grade at Indianapolis Public School No. 23, but he did not attend high school, where he would have been prohibited from playing on school athletic teams in any case.19 After finishing school, he likely went to work to supplement the family income. He also reputedly spent time as a batboy for the ABCs, whose home park was located within just a few blocks of the peripatetic Charlestons’ Indiana Avenue homes.20

Alas, you can’t be a batboy forever, and the work then available to a Black teenager in Indianapolis could not have been particularly rewarding. The United States military offered an attractive alternative. So in early 1912, fewer than two years after he had completed his eighth grade year, Oscar Charleston decided to join the Army. Giving his birthday as October 14, 1893 (rather than 1896), he enlisted on March 7, 1912. Oscar was accepted and assigned to the 24th Infantry, Company B. On April 5, he shipped out for the Philippines.

During his three years of service in the Philippines, Charleston’s prowess on the diamond made him a star. There were “few more popular baseball players in the islands than Charleston,” claimed the Manila Times, and “everybody knows that he is the boy to make good in any position.”21 The position at which Charleston made good was not center field, where he would later excel, but pitcher. In July 1914, after the completion of the 1913–14 professional Manila League season in which Charleston’s all-Black 24th Infantry regiment had fielded a team, he was chosen by Manila’s Cablenews-American newspaper to be its starter in an exhibition game against the rival Manila Times. Just seventeen at the time, Charleston hurled a one-hit shutout for this integrated all-star team, striking out ten and walking two. He also hit a triple.22 (The catcher for the Manila Times club that day was Charles Wilber Rogan, later known as “Bullet” or “Bullet Joe,” and possibly the greatest two-way player of all-time.23 Rogan was Charleston’s usual receiver on the 24th’s regimental squad, which obviously had a heck of a battery.)

We get a glimpse into this period of Charleston’s life from a letter he saved in his personal scrapbook. Dated August 1, 1914, the letter was written by an acquaintance stationed at the headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary in Manila. The all-star game in Manila had prevented Charleston from keeping an appointment with the writer, who excuses him for his absence. After all, “All of us and 90% of the fans around Manila, believe that in addition to being the best pitcher in the Philippine Islands, you are also all around, the best ball player in this neck of the woods.” The writer signs off by assuring Oscar that “Captain Loving and Mr. Waller join me in wishing you success in all your undertakings.”24

Among other things, this letter indicates that at a young age Oscar was already taking delight in, and had a talent for attracting, thoughtful companions. The Captain Loving mentioned in this letter was Walter Howard Loving, leader of the constabulary band, which he had led at William Howard Taft’s inaugural presidential parade in Washington, DC. In 1914, Loving was in the midst of a long and distinguished military career that would include serving as an undercover agent for the US government during World War I. Few Black Americans in the Philippines would have been more prominent than Loving. To have established a friendly acquaintance with him as a seventeen-year-old private must have been quite a thrill.25

Charleston’s scrapbook and photo album make clear that throughout his life he maintained an interest in music and ideas, and that he tended to seek relationships with others who shared these interests and who were striving to rise socially. This very much includes his two wives, Hazel Grubbs and Jane Blalock Howard, who were highly intelligent and came from respectable, ambitious, pillars-of-the-community sorts of families. A rounded view of Charleston’s life indicates, in other words, that he would have hated being regarded as a thug—a fact which makes his early troubles controlling his temper all the more poignant. Not until late in his life was Charleston able to consistently overcome this family legacy.26

BEGINNING WITH THE ABCs

After his discharge from the Army in March 1915, Charleston headed home to Indianapolis, where he presented himself to Indianapolis ABCs manager C.I. Taylor. (Taylor’s full name was Charles Isham, but he was universally known by his initials.) Taylor had purchased a half interest in the ABCs in 1914 from Thomas Bowser, a White bail bondsman who had bought the team from Ran Butler in 1912. In the last years of Butler’s ownership, the ABCs’ talent and fan support had declined. The late Butler years saw the team playing mainly at home, presumably to save money, and using gimmicks like a 793-pound umpire known as Baby Jim to lure folks to games.27 It took just one year for Taylor to begin to change the ABCs’ fortunes dramatically.

Rube Foster is more commonly named as early Black baseball’s most important institutional pioneer, but C.I. Taylor was nearly as formidable as Rube—and significantly less given to chest-thumping egotism than his rival. Like the rotund Foster, the thin C.I. was a southern minister’s son. He was also an Army veteran and a graduate of Clark College in Atlanta. Aside from his consuming commitment to baseball, this background played out in predictable ways: C.I. believed in self-help, discipline, practice, conditioning, and strategy—“scientific” baseball, as it was called at the time. He detested rowdiness, drunkenness, and gambling, and surrounded himself with intelligent, well-mannered men. At least two of his players published poetry, many were recruited from Black colleges, and a number went on to successful managerial careers. C.I. was civically active, too, the sort of man who served on YMCA fundraising committees. His managerial efforts led to increased community support for the ABCs, more stadium improvements, and—gradually, haltingly—a more female- and family-friendly game environment.28

Of course, winning was also high on the list of things three of his brothers—Ben, Candy Jim, and Steel Arm Johnny, all of them college men like C.I.—were exceptional ballplayers themselves. They didn’t always play for C.I.’s teams, but when they did, they were a tremendous help. When C.I. came to Indianapolis from West Baden, Indiana, where he had been leading a team called the West Baden Sprudels, he brought Ben, a first baseman, with him. From the Sprudels he also brought to Indy pitcher William “Dizzy” Dismukes (later to become Buck O’Neil’s beloved mentor), outfielder George Shively (a resident of Bloomington, Indiana), and light-hitting shortstop Morty “Specs” Clark.

Thanks to C.I., by early in the 1915 season the ABCs had accumulated a good deal of talent. Taylor, Shively, Clark, third baseman Todd Allen, and catcher Russell Powell formed the position-player core. The starting pitching rotation was anchored by Dismukes and Louis “Dicta” Johnson, an accomplished spitballer (at the time a perfectly legal, if unhygienic, pitch). Former Sprudel second baseman Elwood “Bingo” DeMoss—according to Bill James, the best bunter in Negro League history—came on board in early May.29

Shortly after Oscar got back to Indianapolis in spring 1915, he presented himself to C.I. Taylor for a tryout.30 Taylor knew he had something special on his hands. By April 9, he was telling the local papers that he had signed a “crack southpaw.”31 Two days later, at Northwestern Park, a couple of blocks from where his family now lived, Oscar’s stateside career in professional Black baseball began.32 Taking the mound against the semi-pro Indianapolis Reserves, he notched a shutout, giving up two hits in the first inning, but only one more the rest of the game. He also struck out nine, walked none, and pitched six perfect innings.33

Oscar’s start seemed to augur a future as a mound ace, but the second game Charleston pitched in 1915 for this talented ABCs team complicated things. Against a team of White minor-league players calling themselves the All-Leaguers, he gave up six runs in the ABCs’ loss. He also homered to right and was robbed of another hit when the left fielder snared a line drive. The 18-year-old Oscar’s home run was “one of the longest drives seen at the local park” and the longest ever to right field, claimed the Indianapolis Freeman. Charleston had not been back in the States for a month, but he was already being hailed as “one of the most promising young pitchers seen at Northwestern park. He pitches like a veteran, besides fielding his position and batting in great fashion. The fans should watch this youngster, he will be one of the best.”34

The following Sunday, Taylor had Oscar in center field for a rematch with the All-Leaguers. The ABCs had been left with a hole in the outfield when Jimmie Lyons jumped to the St. Louis Giants, so to the outfield Oscar went.35 He homered yet again in the ABCs’ 14–3 victory.36 Charleston’s bat was far too valuable not to be in the lineup every day. Oscar would start on the mound four days later, but for the rest of the season he would serve only occasionally as a starting pitcher. No one complained. Oscar’s fielding, baserunning, and his power, in that order, stood out much more than his pitching.

By June, when the Indianapolis Freeman ran photos of the speedy ABCs outfield of George Shively, Charleston, and midseason addition Jim Jeffries, the paper was claiming that “[t]his trio of outer gardeners looks to be the best in the game.”37 In the Black game, at least, that was probably not an exaggeration. Even when Charleston screwed up—as he did on June 24, when he misplayed an easy fly to center against the Chicago American Giants, allowing the winning run to score in the five-game series’ rubber game—he was liable to redeem himself in short order. Thus, a few days after that costly error against the Giants, when the ABCs took on the Cuban Stars before a record crowd at Northwestern Park, he made what the Star called “two remarkable running one-handed catches,” one of which led to a double play.38

Against the Indianapolis Merits, one of the city’s strongest White semipro teams, “Charleston made a circus catch in deep center, pulling the ball down with one hand,” helping to win what was billed as the city championship for the ABCs, 14–1.39, 40 Given the short, thin mitts then in use, in 1915 the one-handed catch was comparatively rare, and one gets the impression from contemporary newspaper accounts that Charleston was one of its first impresarios. The press frequently reported that his fielding “featured,” the era’s adjective of choice. Sometimes it was “sensational,” and once it was so good that fans were “startled.” In August, the Freeman praised Charleston for playing center field “for all there is in it.”41 Oscar’s range was most impressive to observers, but his arm was good, too. In games against top-tier opponents, he finished second on the team to George Shively with nine outfield assists.42

The 1915 ABCs liked to run—that was part of scientific baseball, as taught by Taylor and practiced in the big leagues with such flair by Cobb. Against the Fort Wayne Shamrocks, for example, the team stole nine bags.43 Charleston was not the team’s most prolific base stealer, but he held his own with speedy teammates like Shively and DeMoss. In fifty-seven games, he stole fourteen bases and legged out five triples, tied for tops on the team. For a while, later in the year, Taylor batted him leadoff.

Oscar’s power came and went in this rookie season, fading down the stretch as the ABCs faced better pitching and as pitchers seeing Oscar for the second and third time made adjustments. But homering in three of your first six games leaves a lasting impression, especially when they are no-doubters, and especially when you are playing in the Deadball Era. (Against top competition, the mammoth Pete Hill’s six home runs was highest among elite Black professional clubs in 1915.) Oscar was the “slugging soldier,” the “heavy-hitting outfielder,” even though he only hit one more homer the rest of the year.44 At this point in his career, he was only a decent hitter. Overall, he batted .258 against top opponents in 1915. His teammates Shively and Ben Taylor hit significantly better. Oscar’s best series came against the talented Cuban Stars in June, when he went 7-for-19 with a home run, a double, and three stolen bases and helped the ABCs win four out of five.

Charleston may not have been the ABCs’ best player—not yet—but the well-rounded quality of his game led the Freeman to dub him, on one occasion, the “Benny Kauff of the semi-profs.” Kauff manned center field for the Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the upstart Federal League. Brash and flashy, he was well known to locals, first, because he had played center field for the Federal League’s pennant-winning Indianapolis Hoosiers in 1914, and second, because prior to Dizzy Dean he was probably the greatest trash-talker in baseball history. Kauff had no problem saying things like “I’ll make them all forget that a guy named Ty Cobb ever pulled on a baseball shoe,” and “I’ll hit so many balls into the grandstand that the management will have to put screens up in front to protect the fans and save the money that lost balls would cost.” To top it off, he dressed, in the words of Damon Runyon, like “Diamond Jim Brady reduced to a baseball salary size.” With respect to their games the comparison of Charleston to Kauff was not totally inapt, but, unlike Benny, Oscar did not boast in the press—and he didn’t have the funds to indulge in diamond tiepins and silk underwear.45

On the whole, in 1915 Charleston did as well as anyone might hope for an 18-year-old rookie. But there is one indication that there may have been trouble behind the scenes. For a period of at least three games in July, Oscar did not play for the ABCs. No reason for his absence was given in the Star or in the Freeman, but when he returned to the team Elwood Knox of the Freeman referred to his being “back in the fold again.”46 Perhaps he had been injured. Perhaps he and C.I. had butted heads. Perhaps Oscar was having trouble controlling that troublesome family temper.

Pablo Mesa, Oscar Charleston, and Alejandro Oms playing for Santa Clara in Cuba in the mid-1920s. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

THE INDIANAPOLIS POST-SEASON BRAWL

On September 9, 1915, the ABCs played their last game of the year against a top-tier non-White team, winning, 4–2, against the Cuban Stars. They had gone 37–25–1 against the top clubs, and they had absolutely rolled through lesser competition, including contests with White teams like the Chicago Gunthers, the Indianapolis Merits, and the unforgettably-named Terre Haute Champagne Velvets.47

No matter who they had faced in 1915, Dizzy Dismukes and Dicta Johnson had been fantastic at the top of the ABCs rotation, with Dismukes throwing a no-hitter against the Chicago American Giants on May 9 and matching the New York Lincoln Stars’ Dick “Cannonball” Redding pitch-for-pitch in a 1–1, 15-inning tie in which both pitchers went the distance. First baseman Ben Taylor had shown himself one of the best hitters not playing in White segregated baseball, and Shively and DeMoss had also had fine seasons. The ABCs had gone 9–3 against the Chicago American Giants, 13–9 against the Cuban Stars, and 4–4–1 against the Lincoln Stars, the three teams that were their top competition—in the argot of the time, the “fastest” teams out there.48 No one doubted that the ABCs were a very good team. This is how things stood in late September 1915, as the ABCs prepared to undertake what was becoming an annual tradition of postseason games against White all-star teams at Indianapolis’s Federal Park. Since the middle of the season the ABCs had been playing their Sunday home games at this new stadium, thanks to growing crowds that their usual home field of Northwestern Park simply could not accommodate. These all-star teams—the term was used loosely—consisted largely but not exclusively of Indianapolis natives returning home after their seasons in minor league ball had ended, as well as players from the high-minors Indianapolis Indians and other city teams.

The papers loved these games. The daily Star promoted them heavily, breathlessly reporting who and who would not play for the all-star teams, inserting editorial asides about the relative strength and hopes of the teams, printing trash talk, playing up the racial rivalry angle, and fairly openly taking the side of the White teams as the games went on. For the brawl that occurred on October 24, the White press shoulders at least a little of the blame.

The first games were scheduled for Sunday, September 26. “The colored champs”—the ABCs, that is—“had fairly easy sailing on their trip over the state” recently, admitted the Star; the ABCs had beat up on teams from Kokomo, Rochester, Columbus, and other Indiana burgs. But “Sunday it is thought they will meet with stronger opposition.”49 The White all-stars would include players from various leagues in and levels of the minors. The ABCs would be tested, predicted the Star. “The ABCs always take delight in polishing off any league teams, but they probably will be forced to step at their best today to turn the trick.”50 Eh, not really. The team of mostly low-minors “all-stars” that showed up on September 26 was no match for Taylor’s club, which won the first game, 12–1, and the second, mercifully shortened after five innings by darkness, 7–0. Collectively, Dicta Johnson and Dismukes gave up seven hits on the day. Charleston went 2-for-8 with two stolen bases. The ABCs stole 11 bags in game one alone. “Manager Taylor of the ABCs has drilled so much base-running knowledge into his colored champs that it is going to take an all-powerful outfit to grab a game from them,” conceded the Star.51

The White players set out to put together such a club. Frank Metz, who played first base for the American Association’s Indianapolis Indians, organized a new squad to take on the ABCs the following Sunday. The Indians’ Joe Willis, who had had a brief major-league career with the Cardinals, would pitch, and several other Indians and players from the Louisville Colonels would join in. “It looks like the ABCs are due for a trouncing Sunday when they battle Frank Metz’s All-Stars at Federal Park,” chortled the Star.52 The all-star outfield was “expected to show something in the way of distance slugging,” and Smiling Joe Willis’s left-handed pitching would “prove quite puzzling to the colored champs.” Willis even called his shot: “[T]he big fellow says he’ll win if given a few runs.”53 Metz’s all-star team proved much better than the previous Sunday’s, but still it could not beat the ABCs, the game ending in a 3–3 tie after 12 innings. Dismukes pitched seven innings of no-hit ball in relief of Dicta Johnson, and Charleston went 3-for-5 with a stolen base. Three thousand fans saw a “spicy game” full of “swell stops and neat catches,” but no winner.54

By now the big-league season was over, and there was no more messing around. Indianapolis native son Donie “Ownie” Bush was coming back to town, and he would lead the all-stars the following Sunday against the ABCs, just as he had the previous year, when his all-stars had gone 2–2 against Taylor’s club.55 Bush, twenty-eight, couldn’t hit his way out of a paper bag, but he was fast, exceptionally disciplined at the plate (he had led the American League in walks five times already), and a slick fielder at shortstop. That combination of talents was good enough to place him third in the MVP voting of 1914. With him would not be Ty Cobb, who had better things to do, but three other Tigers teammates: outfielder Bobby Veach, who had led the AL in both doubles and RBIs that year; George “Hooks” Dauss, who had won twenty-four games with a 2.50 ERA and was also an Indianapolis native; and George Boehler, a reliever from nearby Lawrenceburg, Indiana. Also scheduled to play was the Yankees’ Paddy Baumann, yet another Indianapolis man who as a utility player had just hit .292.56 This new all-star team was a different beast. Bush’s club beat the ABCs, 5–2, on October 10. Dauss and Boehler frustrated the ABC batters with curves, striking out 12. Oscar went 0-for-4.

The ABCs were a “disappointed lot.”57 Two games remained in the series, and these were the only contests all year in which they could show to others, and to themselves, how well they stacked up against major-league, or at least near-major-league, competition. Then, too, the racially tinged needling of the White papers had to rankle. As the Star wrote the next week, apropos of nothing at all, “The All-Stars expect, next Sunday, to teach Tom Bowser’s men their ABCs.”58 Taylor had his club practicing all week. On Thursday, Bush announced that the Brooklyn Robins’ Dutch Miller would be added as the All-Stars’ catcher. C.I. responded by welcoming back Jimmie Lyons as his right fielder. Unfortunately, Dismukes had decided to head to Honolulu with Rube Foster’s American Giants, so Dicta Johnson would start this time for the ABCs, while for the all-stars the White Sox’s Reb Russell would fill in for Hooks Dauss, whose wife had taken ill. Russell had just posted a 2.59 ERA for the Sox, so this was not necessarily a downgrade.

Four thousand, five hundred fans showed up at Federal Park on the afternoon of Sunday, October 17. They watched Dicta Johnson throw a masterful game, giving up only four hits over eleven innings. The ABCs, sporting new uniforms for the occasion, finally won, 3–2, on Ben Taylor’s walk-off (the term wasn’t used then) base hit that scored Shively from second. It was far from a boring game. In fact, “until the deciding run was registered in the eleventh the fans were kept in an uproar by sensational plays on both sides.”59 Oscar, who had turned 19 three days earlier, went 2-for-4 with a double off the Mississippian Reb Russell, who “would no doubt draw the color line in the future,” chuckled the Black Freeman.60

The rubber game was set for the next Sunday, October 24. Excitement was high, and it built even more when it was reported first that Benny Kauff himself was headed to town to play for the all-stars, and next that Cannonball Redding, “the best colored hurler in the business,” would pitch for the ABCs.61 Redding wasn’t just coming to Indianapolis from New York for one game. In early October, C.I. had announced that his club would undertake a Cuban tour immediately after the season’s end. The ABCs were scheduled to leave right after this final game of the season, and Redding would accompany them. Reb Russell, allegedly angry over his defeat, would take the mound again for Bush’s club. The day finally arrived. The all-star team wasn’t at its best. Kauff had not made it, and neither Veach (who had only played the first game) nor Miller would play. Bush, Baumann, and Russell were the team’s only true big-leaguers. Perhaps that only put the ABCs more on edge. Not only were they tired from the long season, but with the all-stars not even at full strength the ABCs had to win this game—especially with five thousand screaming fans in the stands.

The all-stars scored first, plating one in the top of the second. In the meantime, the ABCs were having trouble solving Russell. When the fifth inning began, it was 1–0 all-stars. Donie Bush made it to first. Then he took off on Redding. ABCs catcher Russell Powell threw to second, where Bingo DeMoss was covering. The throw beat Bush, but umpire Jimmy Scanlon, who was White, signaled safe.62 That’s when all hell broke loose.

Like Tris Speaker, to whom he would later be frequently compared, Charleston played a famously shallow center field, and when Bush started for second [base] he no doubt sprinted in to back up the play. After Scanlon’s safe signal, he was already close to the action when he saw DeMoss lose it. DeMoss pushed Scanlon, then swung at him. Scanlon put up his fists, and the men began to grapple. A moment later, Oscar, still running at top speed, arrived and clocked Scanlon. His punch to the umpire’s left cheek left him gashed, bloodied, and lying on the ground.63

Umpires were not immune to the violence that was common on the field in those days. Earlier that season at Northwestern Park, an umpire had allegedly hit Chicago American Giants outfielder Pete Hill over the head with a pistol—the mere fact of pistol-packing umpires gives one some idea of the temper of that era.64 But still, for a Black man playing in a mixed-race game to slug a White umpire who was already engaged with another Black player was to cross any number of lines, and Charleston must have known that immediately. If he didn’t, the enraged fans that began to stream onto the field probably clued him in. Players from both teams also began to converge on the action at second base. The police—twelve patrolmen and six detectives—were close behind. The scene was chaotic. Just who fought whom is unclear, but it seems that most of the combat now took place between fans—it was very nearly, said the next day’s Star, a full-fledged “race riot.” The police used their billy clubs freely to break up the fighting. Several drew revolvers, but did not use them. The players themselves, from both teams, tried to restore order. Finally, the police gained control of the situation and the fans returned to the stands.

Oscar Charleston poses with his second wife, Jane Grace Blalock of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, whom he married in November 1922. The photo was probably taken in Cuba, where Oscar played winter ball, shortly thereafter. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Oscar, if the Star’s account can be credited, had slipped away. The Star claimed that “he kept on running” after decking Scanlon, and if that was true it was the last time he ever ran away from a fight. He may have been genuinely scared for his life. The Indianapolis of 1915 wasn’t all that friendly to Blacks in the first place, and Blacks who assaulted White representatives of authority were not exactly assured of dispassionate justice.65 “The police had considerable trouble finding” Oscar, reported the Star, but eventually they located him. He and Bingo were placed under arrest and carted off to jail. The game, amazingly, then continued, Scanlon still umpiring. The ABCs, perhaps pondering whether and how they would get out of the park unscathed, managed just one hit in the game and were defeated, 5–1.

C.I. Taylor was embarrassed, dismayed, furious. Not only did he deeply wish to make baseball a more reputable activity, his entire identity was centered on being a respected member of the Indianapolis community. He knew that this ugly incident in a White ballpark would be held against all of the African American residents of the city as proof of their ineradicable savagery, especially at a time when a fresh wave of Black migrants from the South was contributing to heightened racial tensions. But he had made arrangements to take this team to Cuba, and, probably realizing that the best thing to do was to get the club out of town as quickly as possible, he went forward with his plans. His co-owner Tom Bowser bailed Oscar and Bingo out of jail, and by evening the ABCs were embarked on their journey.

When the team’s train stopped in Cincinnati, Taylor wired the Star with a statement. He made it clear where his sympathies lay. Not with his young players—and especially not with Oscar.

That was a very unwarranted and cowardly act on the part of our center fielder. There can be no reason given that will justify it. Umpires Geisel and Scanlon are gentlemen. I am grateful to Bush and Bauman (sic) and all the players of the All-Stars for their earnest efforts to ward off trouble and their kind words to me after the incident. The colored people of Indianapolis deplore the incident as much as I do. I want to ask that the people do not condemn the A.B.C. baseball club nor my people for the ugly and unsportsmanlike conduct of two thoughtless hotheads. I can prove by the good colored people of Indianapolis that I stand for right living and clean sport. I have worked earnestly and untiringly for the past two years in an effort to build a monument for clean manly sport there and am sorely grieved at the untimely and uncalled for occurrence at Federal Park today. Again I ask that the people do not pass unjust judgment on my club or me.66

It must have been an awkward trip to Florida. Bingo DeMoss had started the fight, but it was Oscar who took all of the heat. His actions had escalated things terribly, but from his point of view, he had come to a teammate’s aid.67 Was that entirely wrong? It would remain true throughout his career: Oscar didn’t usually start fights, but he loved to join them. And when he came to your aid, it was with fists flying. The man was simply not a natural peacemaker.

The next day, Oscar and Bingo were formally charged with assault and battery, and their case continued until November 30. A couple of days later they and the rest of the ABCs disembarked in Havana.

LETTERS FROM CUBA

By the time he reached Cuba, Oscar had cooled off. On November 1 he sent a statement to the Freeman. It is the first time we hear his voice in the historical record:

Realizing my unclean act of October 24, 1915, I wish to express my opinion. The fact is that I could not overcome my temper as oftentimes ball players can not. Therefore I must say that I can not find words in my vocabulary that will express my regret pertaining to the incident committed by me, Oscar Charleston, on October 24th.

Taking into consideration the circumstances of the incident I consider it highly unwise and that is a poor benevolence. I am aware of the fact that some one has said that they presume I am actuated by mania, but my mind teaches me to judge not, for fear you may be judged.

Yours respectfully,

Oscar Charleston68

Was the “some one” who had accused Oscar of “mania” C.I.? It isn’t clear. In any case, the apology was good enough for the Freeman, which encouraged readers to accept it. The paper emphasized that Oscar had “become exceedingly sorry.”

An apology was due from Mr. Charleston, a fact which finally dawned on him. He has done the very graceful thing in acknowledging his error, and which leaves him no less a man. The bravest are the tenderest. Considerable harm has been done because of the happening, and which a string of apologies from here to Cuba could never altogether righten. However, he has helped some, and he has set himself right individually and with his team and race.69

C.I., on the other hand, remained angry, even after a few days in the Caribbean. He remained eager to deflect any blame from landing on his own head. Four days after Oscar wrote his apology, Taylor sent from Cuba another statement about the whole affair in which he partially excused DeMoss but continued to take Charleston to task.

I am very grieved over the most unfortunate and degrading affair pulled off by DeMoss and Charleston. Umpire Scanlon was wholly blameless. His decision might have been questionable, but there is not one word that can be said justifying the perpetrators of that unfortunate and untimely happening. It was an awful climax of my last year’s work.

I feel that I should not be censured for the conduct of these two men. Neither should our club, for I do not believe that there is any man on the club outside those two who would have committed such an ungentlemanly and unsportsmanlike act. Every member has expressed to me his deepest regrets. And, too, I believe that if DeMoss had any idea that things would have turned out as they did he would not have raised a hand to push the umpire. Remember we are not trying to shadow him for his actions. He needs no defense—he was wrong. But knowing him as I do, I am fully convinced that his conduct was worse than his heart.

As far as Charleston is concerned, he really doesn’t know. He is a hot-headed youth of twenty years [actually nineteen; either C.I. was mistaken or Oscar had lied about his age] and is irresponsible, who is to be pitied rather than censured.70

It all added up to a bad time for Oscar in Cuba, a place Black teams had been visiting in the late autumn almost every year since 1900. Following the established tradition of the “American Series,” the ABCs were installed at Havana’s Almendares Park, where they played twenty games against three Cuban teams—Habana, Almendares, and San Francisco—between October 30 and December 2.

In subsequent years, Oscar would perform so well in Cuba that he would become a national legend. But with the brawl still fresh and his manager criticizing him in the press, in 1915 he could not get going. He batted .191, showing no power (he had only two extra-base hits in 77 plate appearances), and was caught stealing on half of his attempts. Taylor started him on the mound once and he was hammered, giving up ten runs, eight earned.

Certainly the competitive and proud Oscar must have been in a sour mood, which couldn’t have helped advance the cause of reconciliation with C.I. On November 25, midway through the ABCs’ Cuban tour, Taylor announced that he had kicked Oscar off the team. He had “persisted in disobeying club rules.”71 The expulsion didn’t last long: Oscar missed exactly one game. After the ABCs played their last game on the island on December 2, finishing their tour with a record of 8–12, Charleston returned to Indianapolis with the team.72

THE CONSEQUENCES

Charleston and Bingo had missed their November 30 trial date, of course—costing Bowser his $1,000 bond—and were promptly rearrested upon their return to Indianapolis. Their trial took place on December 7, Scanlon testifying for the prosecution. Judge Deery dealt with them leniently. Neither would have to serve any time. Oscar was fined ten dollars plus court costs, and Bingo five dollars plus costs.73 The legal drama was at an end, but the ramifications of the brawl were still playing out. Several days before the trial, the police used the fight as an excuse to declare that no games between Black and White teams would henceforth be allowed in the city. “It occurs to me that it is time to call a halt in baseball playing between Whites and Blacks when two teams of mixed colors cannot play a game without trouble,” announced a police captain. It was a good time to make such an announcement, since Blacks could be blamed for the decision. “I have talked to several witnesses, and there is no doubt but what the two colored players incited trouble.”74 The city’s decision looked like a blow to the ABCs, who had played a couple dozen games against White teams in 1915. This step backwards was exactly what C.I. Taylor had feared.

A few years later, Donie Bush, enraged by a call, punched umpire Bill Dinneen “in the stomach and jaw” in a major league game. He wasn’t even ejected—not until after the inning ended, anyway, when he threw a ball at Dinneen.75 Bush and Charleston weren’t so different from each other after all, or from the other rough-edged players of the Jazz Age. Both were intense, competitive, widely respected men. It’s not too surprising to learn that, sometime after the ugly incident at Federal Park, these baseball lifers began to call each other friend.76

Perhaps because he was Black, Charleston’s temper exacted a far higher reputational cost than did Bush’s. As player, manager, and scout, Oscar Charleston would go on to compile one of the finest baseball résumés of any player of any race.77 Yet more than a century later, the capsule narrative about him remains distorted by the ugliness that marred the end of his rookie season. That is how the myth began, and one of the reasons why the full truth about Charleston remains obscured.

JEREMY BEER is at work on a biography of Oscar Charleston for the University of Nebraska Press. He is the author of “The Philanthropic Revolution: An Alternative History of American Charity” and the editor of “America Moved: Booth Tarkington’s Memoirs of Time and Place, 1869–1928.”

Notes

1 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract, rev. ed. (New York: Free Press, 2001), 358. James defends this ranking at some length in the pages that follow.

2 James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract, 189.

3 Quincy Trouppe, Twenty Years Too Soon: Prelude to Major-League Integrated Baseball, rev. ed. (St. Louis, MO: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1995 [1977]), 118.

4 Buck O’Neil, I Was Right on Time: My Journey from the Negro Leagues to the Majors (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 25.

5 William F. McNeil, Cool Papas and Double Duties: The All-Time Greats of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001), 192.

6 See http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?ID=134&tab=2. First developed by Bill James, a win share is a comprehensive measure of player value that takes into account, at least theoretically, both offense (including baserunning) and defense.

7 See Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2010 [1984]), 114; and Joe King, “Campanella Not Antique But Modernizer,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1951, 3. My thanks to Neil Lanctot for leading me to these sources.

8 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884 to 1955 (New York, NY: Birch Lane Press, 1995), 87.

9 Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 277.

10 Mark Ribowsky, The Power and the Darkness: The Life of Josh Gibson in the Shadows of the Game (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 45–46.

11 Charles Leerhsen, Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 331. Leerhsen documents the violence characteristic of baseball during the Cobb era in numerous other places throughout this biography.

12 Charleston’s personal scrapbook and photo album attest to this judgment. The scrapbook includes numerous boxing-related clippings, including a Cuban-newspaper story about Charleston going into the ring himself in Cuba. Oscar’s brother Roy was a prominent and successful fighter in Indianapolis. The Charleston scrapbook and album are kept at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. They were acquired by historian Larry Lester from Charleston’s niece Anna Bradley, who seems to have acquired them from Oscar’s sister Katherine. Lester also acquired and donated to the museum Oscar’s collection of Cuban cigarette baseball cards.

13 John Schulian, telephone interview, November 7, 2015. Schulian’s article on Charleston is the best piece ever written about the man. It is collected in Schulian’s Sometimes They Even Shook Your Hand: Portraits of Champions Who Walked Among Us (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011).

14 Rodney Redman, telephone interview, December 28, 2015; Mamie Johnson, telephone interview, August 12, 2015; James Robinson, telephone interview, December 28, 2015; Clifford Layton, telephone interview, August 21, 2015.

15 The Charlestons probably arrived in Indianapolis in 1896 (1) because the first year in which they are known to have lived in Indianapolis is October 1896, when the newspapers mentioned the birth of a new son, and (2) because in contrast to later editions, the Charlestons are not listed in any Indianapolis city directory prior to 1897, which implies they moved to the city in 1896 too late to be included in that year’s directory. It is possible that the 1896 (or even earlier) directories missed them, of course, but given the frequency with which they were listed thereafter, it isn’t all that likely.

16 City directories make it clear that the Charlestons lived in at least ten different places before Oscar enlisted in the Army in 1912. From Oscar’s birth until he was four, the Charlestons lived in the Martindale neighborhood on Indianapolis’s northwest side, and after that in the Indiana Avenue neighborhood, but no one address and no one street was home for very long.

17 For the story about Oscar’s mother, Mary, see Indianapolis News, August 24, 1901, 6, and September 3, 1901, 9. Several newspaper accounts reveal that Oscar’s brothers Roy and Berl had multiple run-ins with the law. See, e.g., for Roy, Indianapolis News, November 7, 1900, 8, and for Berl, Indianapolis Journal, January 9, 1903, 8. Oscar’s brother Casper is listed as a ward of the Julia E. Work Training School in the small town of Plymouth, Indiana, in the 1910 United States census. The facility, known as Brightside, served as a home and training center for, among others, juvenile delinquents and “incorrigible” children sent there by the courts.

18 See, for example, “Ash Gets Shade in Ten-Round Contest,” Indianapolis Freeman, December 16, 1911, 7; “In the Field of Sport,” Indianapolis Freeman, June 29, 1912, 7; “The New Crown Garden,” Indianapolis Freeman, July 13, 1912, 5; “In the Field of Sport,” Indianapolis Freeman, November 16, 1912, 7; and “Boxing Contest at the Indiana Theater,” Indianapolis Freeman, November 23, 1912, 6.

19 Oscar’s sister Katherine said that Oscar’s highest educational level was the eighth grade in the questionnaire she filled out for the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976. This questionnaire is also the source of the claim that Oscar attended P.S. No. 23.

20 That Oscar served as a batboy for the ABCs was stated in many articles written about him later in life. Since he was in all likelihood the source of this information, it is probably true, though I have not been able to confirm it.

21 The article from the Manila Times was published in the Indianapolis Freeman on January 1, 1916. The Freeman was an African American newspaper that covered the Negro leagues closely.

22 This information comes from Geri Driscoll Strecker’s bio of Joseph Coffindaffer, available at http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/c6fd7724. The Manila Times provided extensive coverage of the buildup to this all-star game and of the 1913–14 Manila League season as a whole.

23 This the opinion of Larry Lester; in fact, he claims that given his prowess on the mound and at the plate, Rogan is the greatest player of all time, period. See William F. McNeil, Cool Papas and Double Duties: The All-Time Greats of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001), 183.

24 This letter is included in Charleston’s personal scrapbook, which is kept at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

25 For information on Loving, see, e.g., Robert Yoder, In Performance: Walter Howard Loving and the Philippine Constabulary Band (Manila: National Historic Commission of the Philippines, 2013).

26 Charleston was married to Hazel Grubbs, of Indianapolis, from 1917 to 1921. Her father, William, was a highly respected school principal, and her mother, Alberta, just as highly respected a music teacher. Oscar married Jane Blalock in 1922. Her father, Martin Luther Blalock, was a prominent A.M.E. minister in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. By the time of Oscar’s death in October 1954, Oscar and Jane had been separated for a number of years.

27 Paul Debono, The Indianapolis ABCs: History of a Premier Team in the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.), 41. Although I have pieced together what follows from primary sources, Debono’s book is a valuable source of material for and helpful guide to ABCs history.

28 The portrait of Taylor here is drawn based on information taken from numerous contemporary newspaper articles, but see also Debono, The Indianapolis ABCs, 30–71, inter alia.

29 James, The New Bill James Historical Abstract, 176.

30 Dizzy Dismukes, “Dismukes Names His 9 Best Outfielders,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 8, 1930, 14. This article is also included in Charleston’s personal scrapbook.

31 “A.B.C.s and Reserves Play at Northwestern,” Indianapolis Star, April 9, 1915, 10.

32 1812 Mill. The house—and most of the street—is gone today, as is every other of the ten or more in which Charleston lived as a youth, as far as I can tell.

33 “A.B.C.s Shut Out the Reserves by 7–0 Score,” Indianapolis Star, April 12, 1915, 10.

34 “A.B.C.’s Lose to the All Leaguers before Large Crowd—Pitcher Charleston Looks to Be a Wonder,” Indianapolis Freeman, April 24, 1915, 5.

35 Lyons was known, like numbers of obviously good outfielders in the Negro leagues, as the “Black Ty Cobb,” a designation often wrongly implied to have been more or less exclusively used for Charleston.

36 “Colored Boys Slug Ball, Beating All-Stars, 14 to 3,” Indianapolis Star, April 26, 1915, 8.

37 “The Fast and Hard Hitting Out Field of the A.B.C. Ball Team,” Indianapolis Freeman, June 19, 1915, 4.

38 “Cuban Stars Defeat the A.B.C.s in Flashy Game,” Indianapolis Star, June 28, 1915, 8.

39 “Merits Have Been Hitting Ball Hard; Play A.B.C.s Sunday,” Indianapolis Star, June 4, 1915, 10.

40 “A.B.C.’s in Form and Merits Have No Chance,” Indianapolis Freeman, June 12, 1915, 4.

41 “Notes of the A.B.C.’s and Lincoln Stars,” Indianapolis Freeman, August 21, 1915, 4.42. These statistics and all

42 These statistics and all others, unless otherwise noted, are taken from Gary Ashwill’s invaluable Seamheads.com, with data input from Larry Lester and Wayne Stivers, which provides the best currently available Negro Leagues stats (they are more reliable than those found at baseball-reference.com). Seamheads counts only games against top-flight competition. For our purposes here, that means solely games against major Black professional teams.

43 “A.B.C.s Win at Fort Wayne,” Indianapolis Star, September 15, 1915, 8.

44 “A.B.C.’s Trim Gunthers,” Indianapolis Freeman, July 17, 1915, 4;“Notes of the A.B.C.’s,” Indianapolis Freeman, July 17, 1915, 4.

45 This information on Kauff is taken from David Jones’s excellent SABR BioProject article on Kauff. See http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4a224847.

46 “Notes of the A.B.C.’s,” Indianapolis Freeman, July 17, 1915, 4.

47 By my count. For what it’s worth, Taylor reported an overall 71-26-3 record going into the game on October 24 against Donie Bush’s All-Stars. Since they played a few games before Oscar arrived, and I am probably missing a few games, Taylor’s claim is probably not too inflated. Champagne Velvet was the name of a pilsner made by the team’s sponsor, the Terre Haute Brewing Company. The brand, allegedly quite popular in Indiana during the first half of the twentieth century, has been recently revived by Bloomington’s Upland Brewing Company.

48 Seamheads gives a triple slash line of .293/.385/.437 for Ben Taylor, .298/.385/.382 for Shively, and .214/.365/.274 for DeMoss. Those lines translate to OPS+s of 172, 156, and 106, respectively. Although these are the best stats we have, keep in mind that they should be taken with a grain of salt, as box scores are sometimes incomplete or contradictory, and some are missing entirely. Charleston’s OPS+ in 1915 was 125.

49 “Stars Play A.B.C.s,” Indianapolis Star, September 21, 1915, 11.

50 “A.B.C.s and Stars Play Double-Header,” Indianapolis Star, September 26, 1915, 21.

51 “A.B.C.s Too Fast for Minor Leaguers,” Indianapolis Star, September 27, 1915, 9.

52 “Chance for All-Stars,” Indianapolis Star, October 1, 1915, 13.

53 “Southpaw in Shape,” Indianapolis Star, October 2, 1915, 13. Both quotes at the end of this paragraph come from this source.

54 “Stars and A.B.C.s in a Drawn Battle,” Indianapolis Star, October 4, 1915, 8.

55 See Scott Simkus, “ABCs vs. Donie Bush All-Stars, 1914,” published on the Agate Type website on December 5, 2006.

56 All of the statistics in this paragraph taken from Baseball-Reference.com.

57 “Work for All-Stars,” Indianapolis Star, October 12, 1915, 13.

58 “Williford at Indiana,” Indianapolis Star, October 13, 1915, 10.

59 “Russell Beaten in Mound Duel,” Indianapolis Star, October 18, 1915, 10.

60 “A.B.C.’s Beat All-Stars,” Indianapolis Freeman, October 23, 1915, 7.

61 “Crandall to Be in All-Stars’ Lineup,” Indianapolis Star, October 24, 1915, 18. The statistics at Seamheads.com show that Redding had compiled a 1.06 ERA over 119 innings in 1915. No one had such numbers at hand at the time, of course.

62 Bush claimed that DeMoss missed the tag. The Chicago Defender, in its game report, states squarely that “Scanlon called what should have been an out safe.” October 30, 1915, 7.

63 My account of this game is taken from the following articles: “Last Game Taken by the All-Stars,” Indianapolis Star, October 25, 1915, 14; “Race Riot Is Balked by Police,” Indianapolis Star, October 25, 1915, 1; “All-Stars Take Last Game,” Indianapolis Freeman, October 30, 1915, 7; “Fight Ends A.B.C. Game,” Chicago Defender, October 30, 1915, 7.

64 “American Giants in Fierce Riot at Hoosier City,” Chicago Defender, July 24, 1915, 7. (The title of the article was sensationalist; there had been an on-field fight, but no riot.) It is also worth noting here that in 1916, DeMoss almost touched off another riot when he punched a White umpire in the face after being called out at home in a game against the Chicago American Giants. Charleston played in that game but was no part of the trouble. Why DeMoss has escaped being portrayed as a troublemaker is unclear. Perhaps it is the friendly-sounding nickname?

65 After all, in 1915 we are not that distant from the 1920s, when an estimated 27 to 40 percent of native-born White men in Indianapolis were official members of the Ku Klux Klan. See The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1994), 879.

66 The text of Taylor’s wire was published in “In the Field of Sport,” Indianapolis Freeman, October 30, 1915, 7.

67 Indeed, this was the Chicago Defender’s view of the matter: “Charleston came to DeMoss’ aid,” it reported. October 30, 1915, 7.

68 “Charleston’s Unclean Act—He Is Very Sorry,” Indianapolis Freeman, November 13, 1915, 7.

69 “Mr. Charleston,” Indianapolis Freeman, November 13, 1915, 4.