|

| https://sites.temple.edu/tudsc/2017/12/20/building-new-wave-science-fiction-corpus/ |

A Sense of Doubt blog post #3988 - New Wave of Science Fiction

Fitting that I am posting this the day after seeing BLADE RUNNER: LIVE.

Adding to that paper whatever I wanted from things I had read, such as John Varley's Titan and Wizard.

But because of the book and the paper, I started a close study of the The New Wave of Science Fiction and its authors.

I read Dune and the next two books. I read a lot of Larry Niven. I read Ursula K. LeGuin. I read Samuel Delaney. I read Harlan Ellison. I read John Brunner, Clifford Simak, James Blish, and Alfred Bester.

Wikipedia

The Rise of Science Fiction from Pulp Mags to Cyberpunk

EDUARDO PAOLOZZI AT NEW WORLDS: SF and ART in the 1960s

W – Michael Moorcock

W – Dangerous Visions, W – New Worlds, W – The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, W – Galaxy Science Fiction

Impact of New Wave Science Fiction

a radical re-evaluation

By Rich Dana (Ricardo Feral)

Fifth Estate # 411, Spring, 2022

In the last several years, Science Fiction, or SF as it is known among fans of the literary genre, has been the subject of several excellent critiques.

In 2018, Alec Nevalla-Lee’s Astounding: John W Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction presented an in-depth analysis of the cultural impact of pulp magazines and the purveyors of the genre’s myth of “the competent man.”

Last year, Representations of Political Resistance and Emancipation in Science Fiction, edited by Judith Grant and Sean Parson, brought together essays by historians and social theorists examining the speculative politics of SF.

The latest entry is a new release from PM Press, Dangerous Visions and New Worlds, in which editors Andrew Nette and Ian McIntyre take a deep-dive into the highly influential and equally underappreciated works of the SF New Wave, whose more famous members included Ursula K Le Guin, Octavia Butler, William Burroughs, Joanna Russ, Samuel R. Delaney, J.G. Ballard, and Philip K. Dick.

The book’s title is drawn from Harlan Ellison’s anthology Dangerous Visions and the UK SF magazine, New Worlds, edited in its heyday by Michael Moorcock. The subtitle of the book references the years 1950-1985, which in SF are the period between the decline of the so-called Golden Age and the rise of the Cyberpunk era. The book focuses primarily on the period from the late 1950s to the early 1970s known as “the long sixties.” During this period of worldwide cultural upheaval, art, film, literature, and science were all rocked from their foundations. Science fiction (or speculative fiction as its more literary purveyors sometimes describe it) played a significant role as a testbed for exploring potential political scenarios while testing the boundaries of cultural norms.

The SF New Wave of the long sixties was influenced by the Beats’ literary experiments, the Situationists’ tactics, and psychedelia’s aesthetics. In turn, it continues to influence both popular culture and fine art to the present day. In the introduction, the editors write:

“The impact of New Wave science fiction has, in turn, extended long beyond the heyday of the 1960s and 1970s. Although an explicit and heavy focus on technology returned with cyberpunk in the 1980s, the literary, thematic, and stylistic challenges and innovations presented in the preceding period were largely absorbed and refined rather than removed and rejected. While broader society has significantly changed and moral attitudes shifted, many of the social issues addressed by New Wave authors either remain or have been intensified, giving this body of work continued relevance.”

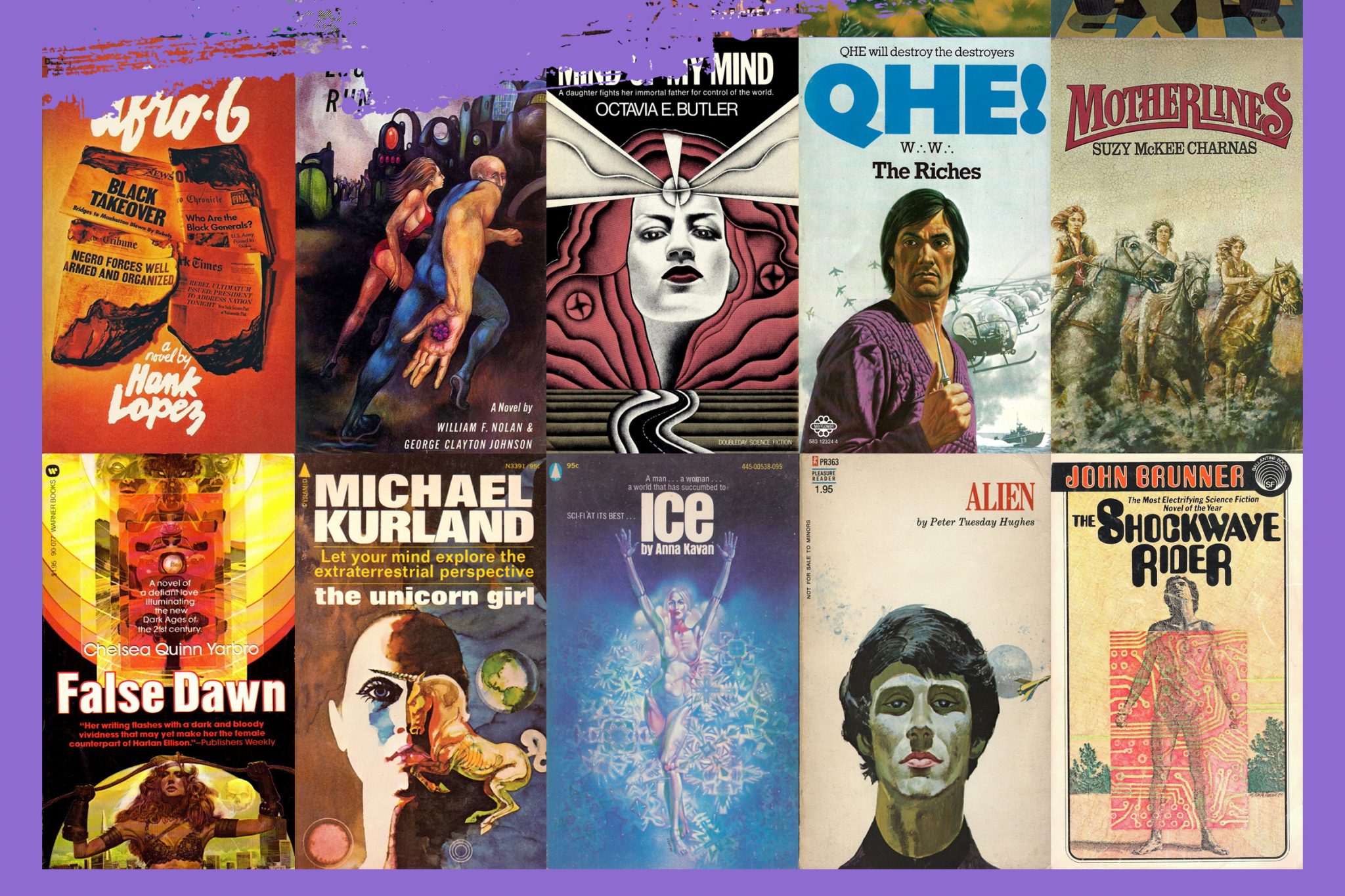

The book is visually stunning and graphically rich. In the introduction, the editors point to the changes in publishing that brought about the decline of pulp magazines and the rise of the paperback novel. The role that paperback cover art played during this period cannot be overstated, and the plethora of illustrations are a joy to experience.

From classic 1950s commercial illustration to full-on psychedelia, Italian Futurist-inspired abstractions to medieval heraldry, the cover artists of the New Wave era drew readers to the revolving wire bookracks at newspaper stands across the world. The selections are excellent, and the full-color reproductions are good. They are so good that if I have one criticism of the book, it is that there isn’t an essay dedicated to the cover artists, without whom many paperback masterpieces would have never caught the eye of the novice reader.

For the SF fan, the scholar, or the casual reader, the relatively short and very entertaining essays in the book cover all the bases and introduce most of the significant players of the era. Butler, Moorcock, PKD, Delaney, and Le Guin are featured prominently, but so are less mainstream talents like R.A. Lafferty, Judith Merril, Hank Lopez, and the Strugatsky brothers.

Race and gender, nuclear holocaust and environmental catastrophe, pop culture and technology, sex, drugs, and rock and roll all receive thoughtful discussion. Among the highlights for me were Cameron Ashley’s essay “The Future Is Going To Be Boring,” or J.G. Ballard’s “Speculative Fuckbooks: The Brief Life of Essex House” by Rebecca Baumann, and Ian McIntyre’s unexpected “Doomwatchers: Calamity and Catastrophe in UK Television Novelizations.”

The editors note that while some of the writers of the New Wave “…took part in public demonstrations and political action, most opted to undertake activism and sedition via literary expression. In keeping with the anti-authoritarianism of the counterculture, visions for real-world reform and revolution were either fuzzy or aligned most strongly with anarchism and radical forms of feminism.”

No one in the movement was more closely aligned with anarchist thought than Judith Merril. Kat Clay does an excellent job of introducing readers to this underappreciated writer and anthologist in her entry, “On Earth the Air Is Free: The Feminist Science Fiction of Judith Merril.”

On a personal level, I’m grateful for the inclusion of Mike Stax’s essay on Mick Farren, the iconoclastic British prankster, gonzo journalist, SF writer, and frontman of the protopunk band the Deviants. In the mid-1980s, I became friends with Mick during his time in New York, and later, when I started OBSOLETE! Magazine, Mick was OBSOLETE!’s most consistent contributor.

His last SF short story “What is your problem, Agent X9?” appeared in my magazine shortly before he died (onstage, performing with the Deviants.) Stax does an excellent job of placing Farren in the historical context of the New Wave. Farren’s collaborative nature and lack of mainstream success could lead some to mistake Mick for a dilettante.

But one only needs to read Farren’s autobiography, Give the Anarchist a Cigarette, to understand that, more than anyone else, he was a quintessential chronicler of this brief, but essential moment, when art, literature, politics, and technology slammed together in a high-speed freeway pile-up, and post-modern popular culture rose from the wreckage.

Rich Dana, aka Ricardo Obsolete, is a writer, artist, and independent publisher. His most recent book, Cheap Copies! The Obsolete Press guide to DIY Mimeography, Hectography and Spirit Duplication examines the role of analog copy machines in the rise of the Avant-Garde and Radical Underground. Available at obsolete-press.com

Building a New Wave Science Fiction Corpus

For the 2017-2018 Digital Scholarship Center (DSC) annual project, we teamed up with Temple University Libraries’ Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) and Digital Library Initiatives (DLI) to build a digitized corpus of copyrighted science fiction literature. By continuing the DSC’s corpus building project, this in-house resource serves to offer students and faculty more opportunities for “non-consumptive” research and pedagogy in the intersecting fields of cultural study, especially genre studies, and computational textual analysis.

Digitizing the Twentieth-Century Canonical Novel

Last Spring, 2017, the Digital Scholarship Center, under the direction of Prof. Peter Logan and Matt Shoemaker, conducted with DLI a digitization process of copyrighted twentieth-century novels. Peter Logan selected the novels by querying English faculty and graduate students as to which copyrighted works they used most frequently for teaching and research. The first batch of texts for the DSC’s corpus, then, reflects rather closely what we could call the contemporary canon, containing works by a wide-range of authors, from Maxine Hong Kingston and James Baldwin to Vladimir Nabokov and Zadie Smith.

After Temple Libraries purchased editions of approximately one hundred novels, a student worker in Digital Library Initiatives, under the direction of Delphine Khanna, Gabe Galson and Michael Carroll, proceeded to break the book bindings (using the aptly named guillotine) and send the hundreds of paper-sheets through a Fujitsu fi-7460 sheet-feed scanner. These newly digitized texts are currently being checked for errors by DSC graduate student workers, including Emily Cornuet and Crystal Tatis. To facilitate that rather painstaking work, Crystal recently began working directly with ABBYY FineReader to correct the scans, allowing for easier proofreading and the output of corrected text in a range of file formats, from .html to .txt.

As the DSC seeks to grow its corpus of copyrighted texts, besides downloading available texts from resources such as Project Gutenberg, we are seeking out more affordable ways to digitize copyrighted literature, ideally building searchable databases of fields of literature not yet readily available for computational text analysis.

Sifting through the Paskow Science Fiction Collection

Besides its voluminous Urban Archives, the SCRC also houses a significant collection of science-fiction literature. The Paskow Science Fiction Collection was originally established in 1972, when Temple acquired 5,000 science fiction paperbacks from a Temple alumnus, the late David C. Paskow. Subsequent donations, including troves of fanzines and the papers of such sci-fi writers as John Varley and Stanley G. Weinbaum, expanded the collection over the last few decades, both in size and in the range of genres. SCRC staff and undergraduate student workers recently performed the usual comparison of gift titles against cataloged books, removing science fiction items that were exact duplicates of existing holdings. A refocusing of the SCRC’s collection development policy for science fiction de-emphasized fantasy and horror titles, so some titles in those genres were removed as well.

When I started working in the DSC this Fall, SCRC Director Margery Sly kindly gave me a tour of the collection and permission to sort through the hundred-linear foot set of duplicate books. Thanks to the assistance of Crystal Tatis, Jasmine Clark, Luling Huang, and James Kopziewski, we were able to filter through the materials in a matter of months. With that said, a lot of labor can go into corpus building. In this case, without an inventory of the duplicate books, we were forced to filter back and forth through dozens of boxes, selecting various options before we knew what else we would find. While parsing out romance, horror, thriller, young/adult, and fantasy genres, it quickly became apparent that the appeal of many mass-market paperbacks from the 1960s and 70s lay in their cover images and outlandish premises.

Many of these relatively unknown sci-fi novels advertised sensational allegories of alternate American histories and dystopian ecological futures that still resonate in haunting ways with our time. Consider, for instance, such promising titles as The Indians Won (1970), The Day They H-Bombed Los Angeles (1961), The Texas-Israeli War: 1999 (1974), and The Day The Oceans Overflowed (1964). While we did keep many of these gems, we also started to find classic works of that nebulous and contested category of literary style and period, the New Wave of science fiction, stories and novels written approximately from the late 1950s through the mid-70s by such authors as Samuel R. Delany, Joanna Russ, Philip K. Dick, Roger Zelazny, and Ursula Le Guin. It wasn’t until we’d worked our way through more than three quarters of the hundred linear feet that we found Afrofuturist works by Octavia Butler.

These were the writers I had hoped to find, the speculative writers of sci-fi who, since the onset of the 1960s, have imagined, rather accurately, many of our era’s most pressing crises. In The Drowned World (1962), for instance, J.G. Ballard portrays a time when solar radiation has melted the polar ice caps, transforming the cities of Europe and America into islands amidst beautiful, decaying lagoons. While Ursula Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) foreshadows a rather recognizable totalitarian society, Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren (1975) offers a startling, complex vision of a post-apocalyptic American city. Many of the works we selected also fit well with the aesthetics and thematics of a Digital Scholarship Center, including such proto-cyberpunk texts as Jean Mark Gavron’s Algorithm (1978), and the classic anthology, Mirrorshades (1986). Finally, since we wanted texts that would prove interesting for computational textual analysis, the New Wave, with its complex experiments in literary forms, promises to be a particularly useful and timely resource for research.

Digitizing the New Wave of Sci-Fi Literature

With a workflow system already developed, I began this Fall working with DLI’s Gabe Galson and Michael Carroll to initiate this next round of digitization. Michael built an inventory and directed undergraduate workers to begin scanning the materials a couple months ago. As of this week, the last days of the Fall semester, Michael has informed me that DLI has already scanned over 40 volumes, almost one-third of the sci-fi selection. Compared to recently purchased and published classics of the twentieth century, these sci-fi works vary greatly in font and formatting, and the condition of many pages are so dirty that the scanner requires frequent cleaning. It is possible the process of cleaning the texts will also therefore be more onerous.

Hopefully by late Spring, on top of the DSC’s twentieth-century novel corpus and the voluminous materials available for download from Project Gutenberg, the DSC will be able to offer a digitized corpus of New Wave science fiction for those looking to analyze on a large-scale some of the literature most reflective of our seemingly dystopian future. In the meantime, keep on the look-out in the new year for more posts to the DSC blog on the sci-fi corpus, where I’ll try to explore the existing academic scholarship involving distant reading (large-scale textual analysis) of sci-fi lit and I’ll give samples of various research projects that could be conducted with our corpus.

Thanks again to everyone from DLI, SCRC, and in the DSC for their contributions to this year’s DSC project. Over the coming years, the digitized corpus will hopefully continue to grow, as this collaborative venture continues to digitize books not otherwise available for computational textual analysis. For a sneak peek, here is one possible selection of mass-market sci-fi books we could send off to the scanners in the future:

I wasn’t interested in the far future, spaceships and all that. Forget it. I was interested in the evolving world, the world of hidden persuaders, of the communications landscape developing, of mass tourism, of the vast conformist suburbs dominated by television—that was a form of science fiction, and it was already here.

J.G. Ballard, 2008.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2601.17 - 10:10

- Days ago: MOM = 3851 days ago & DAD = 506 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment