|

| https://www.udiscovermusic.com/news/brian-eno-blood-red-film-music/ |

Finding Shore (also 2017) in collaboration with Tom Rogerson.

Reflection is another ambient record in Eno's pantheon of ambient records. This one is truly generative as he helped design an app that generates this music and simple took selections from the app and spliced them artfully together.

The app is only available (as far as I know) for iOS.

A sample of Reflection is included in the content below.

Mostly, what we have here is a collection of links from Eno's Twitter or his re-post site, MORE DARK THAN SHARK.

I had saved a few choice links and stashed them in a post, which is what I often do to save content.

I love these BLOOMSBURY 33 1/3 books on music!! I own several, but I want them all. I should write one.

I donated to Dayal for a time on Patreon, but she never produced anything, so then I dropped my donation. Though I still follow her if she were to post an update.

Anyway...

This post is full of YUMMY Eno content. I am still re-reading my way through his DIARY.

Enjoy.

Reflection

mbient music is a funny thing. As innocuous as it may seem on the surface, it can often be seen as an intrusion, an irritant. Muzak annoyed as many people as it mellowed, to the point where Ted Nugent tried to buy the company just to shutter it. When Brian Eno teamed with guitarist Robert Fripp (planting the seeds that would lead to his epochal Ambient series), the duo played a concert in Paris in May of 1975 that eschewed their Roxy Music and King Crimson fame and was subsequently met with catcalls, whistles, walkouts and a near-riot.

Forty years later, Eno’s ambient works have drifted from misunderstood bane to canonical works. Eno’s long career has taken him from glam-rock demiurge to the upper stratospheres of stadium rock, from the gutters of no wave to the unclassifiable terrains of Another Green World, but every few years he gets pulled back into ambient’s creative orbit. And while last year’s entry The Ship suggested a new wrinkle, wherein Eno’s art songs inhabited and wandered the space of his ambient work like a viewer in an art gallery, Reflection retreats from that hybrid and more readily slots along works like the dreamlike Thursday Afternoon and 2012’s stately Lux.

Like those aforementioned albums, Reflection is a generative piece. Eno approaches it less like an capital-A Artist, exerting his will and ego on the music, and more like a scientist conducting an experiment. He establishes a set of rules, puts a few variables into motion and then logs the results. Reflection opens with a brief melodic figure and slowly evolves from there over the course of one 54-minute piece. It’s not unlike the opening notes of Music for Airport’s “1/1,” with Robert Wyatt’s piano replaced by what might be a xylophone resonating from underwater. Each note acts like a pebble dropped into a pond, sending out ever widening ripples that slowly decay, but not before certain tones linger and swell until they more closely resemble drones. Listen closer and certain small frequencies emerge and flutter higher like down feathers in a draft.

Around the 18-minute mark, one of those wafting frequencies increases in mass and the piece turns shrill for an instant before re-settling. Another brief blip occurs a half-hour in, like a siren on a distant horizon. Between these moments, the interplay of tones is sublime, reminiscent at times of famous jazz vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson’s weightless solos, time-stretched until they seem to be emanating from the moon rather than the earth. As smooth and unperturbed as Eno’s ambient pieces tend to be, these small events feel seismic in scale, even if they are short-lived.

Scale becomes the operative word for Reflection. While the physical editions of the album last just under an hour, Eno conceived of the piece to be the most realized version of his ambient music yet, one without parameters or end. Around 51 minutes in, the music starts to slowly recede from our ears, gradually returning to silence. But there’s a version of the piece for Apple TV and iOS that presents a visual component as well as a sonic version of Reflection that’s ever-changing and endless. As the lengthy press release the accompanied the album noted: “This music would unfold differently all the time–‘like sitting by a river’: it’s always the same river, but it’s always changing.” In this instance, reviewing the actual album feels like taking measure of that river from a ship window; you can sense more changes occurring just beyond its borders.

Eno’s ambient albums have never seemed utilitarian in the way of many other ambient and new age works, but naming the album Reflection indicates that he sees this as a functional release, in some manner. Eno himself calls it an album that “seems to create a psychological space that encourages internal conversation.” It feels the most pensive of his ambient works, darker than Thursday Afternoon. Playing it back while on holiday, it seemed to add a bit more gray clouds to otherwise sunny days. Maybe that’s just an aftereffect of looking back on the previous calendar year and perceiving a great amount of darkness, or else looking forward to 2017 and feeling full of dread at what’s still to come.

MORE ALBUM REVIEWS FOR BRIAN ENO

Brian Eno Launches Sonos

Radio Station With Unreleased Music

The Lighthouse, a new station on Sonos Radio HD, will

broadcast unheard music from Eno’s archive

June 8, 2021

In a statement, Eno said of the new station:

The Lighthouse joins artist-curated Sonos Radio stations from Thom Yorke, D’Angelo, FKA twigs, Björk, and the Chemical Brothers. You can listen to them on Mixcloud or on the Sonos app.

Read Pitchfork’s interview “A Conversation With Brian Eno About Ambient Music.”

A Conversation With Brian Eno About Ambient Music

The unceasingly curious composer on chance, minimalism, and the politics of form.

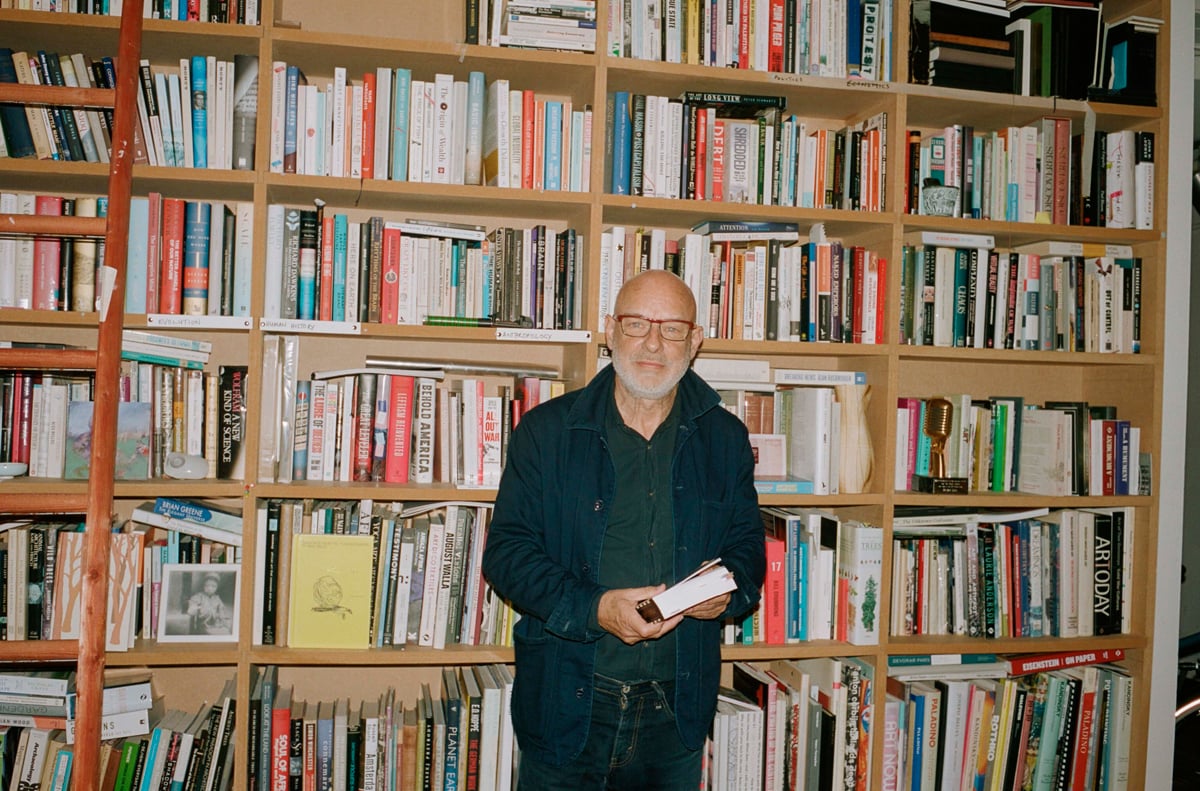

Visiting Brian Eno’s studio in London’s Notting Hill neighborhood, there’s plenty to catch the eye. Shelves sag beneath books and records, a spiral staircase climbs up toward the rafters, and a kitchen table is filled with wine bottles in preparation for a party. Standing in front of a computer monitor, Eno listens to an excerpt of a Baroque opera at formidable volume. Large skylights flood the white-walled space in natural light, and an open doorway affords a tantalizing view into the room where the producer makes his music. Two glowing light boxes, artworks from Eno’s Light Music series—four feet high and priced up to £35,000 apiece—cycle slowly through a series of geometrical shapes in rich pastel colors, like melting blocks of fruit sorbet.

Once the opera stops playing, I ask Eno how long he’s been in this space. “All night,” he says. If that’s true—it’s 10:30 in the morning—he looks remarkably fresh. I clarify: But for how many years? “All night for the past 22 years,” he deadpans. The room’s appeal is obvious; it feels like an oasis. A few tree branches are faintly visible through the skylights, silhouetted against February’s slate-grey sky. The city feels far away.

One of the scene’s most striking details is the way Eno jots down quick notes on his laptop—in pencil, right on the aluminum exterior of the MacBook Pro. The computer rests between us, already covered in scribbles and smeared graphite, when we sit down to talk over cups of almond rooibos tea, and by the end of the hour, fresh markings will have been added to its hieroglyphic tangle: lines of MIDI data, economic diagrams, a pyramid illustrating the hierarchical structure of a symphony orchestra.

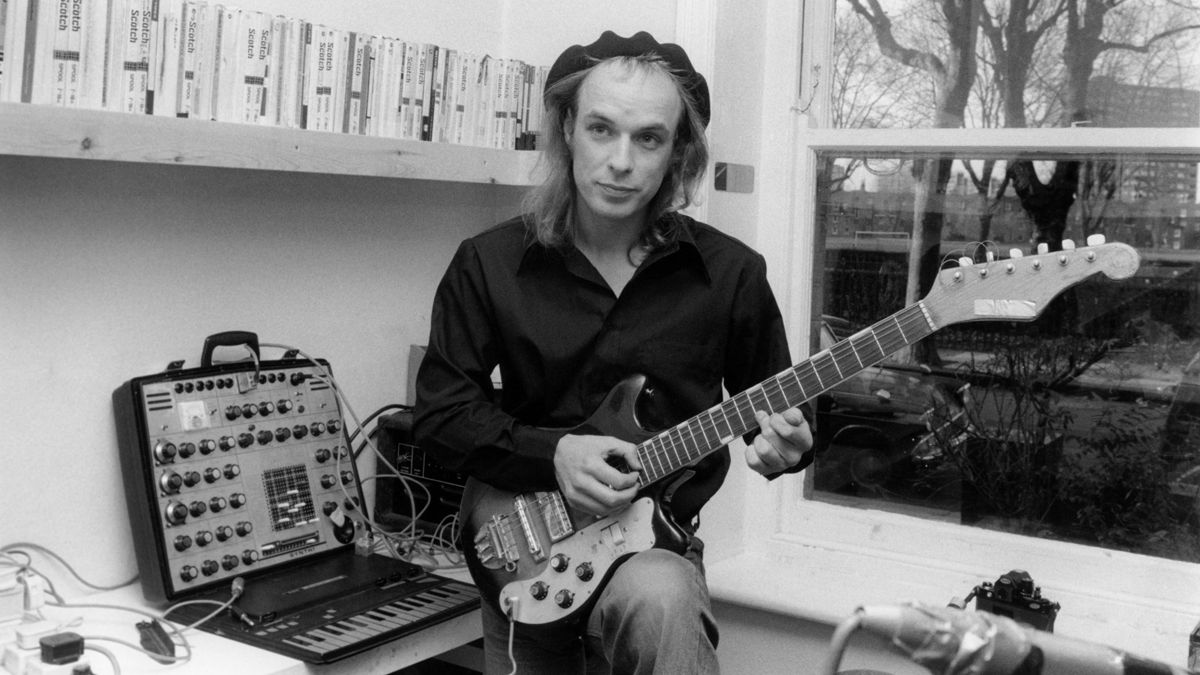

You won’t find that note-taking strategy in any user’s manual, but then, the 68-year-old has made an entire career out of turning convention on its head, from his freeform studio methods to his invention—or advocacy, anyway—of ambient music, a form he once dreamed to be “as ignorable as it is interesting.” Clearly, his counterintuitive instincts are working: In the 44 years since he quit Roxy Music and struck out on his own, he’s made some 50 albums and produced dozens more for artists such as David Bowie, U2, and Coldplay. Not bad for a self-described “non-musician.”

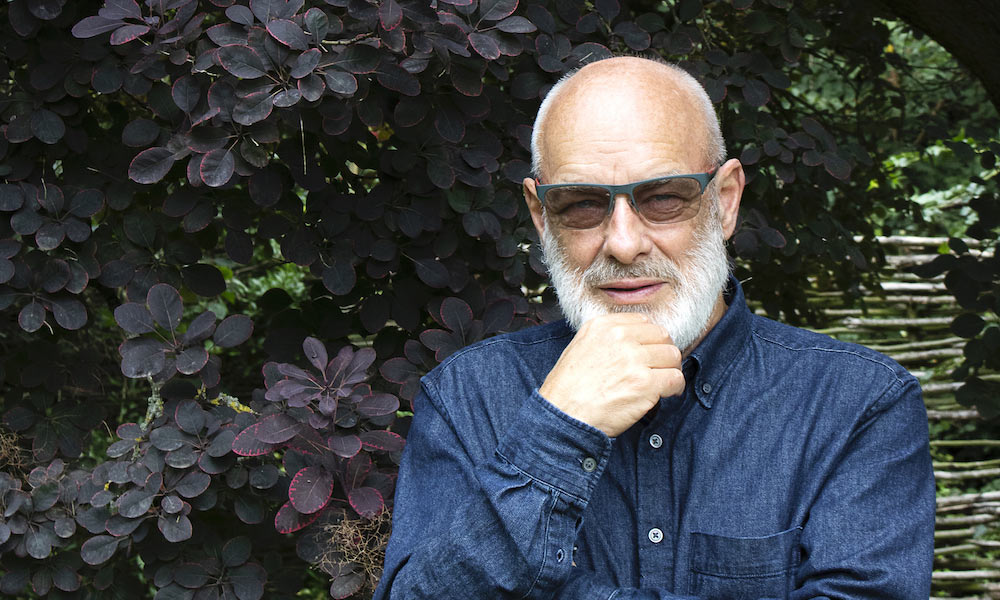

If, once upon a time, Eno seemed the very embodiment of glam panache—eyeliner, feather boas, etc.—these days he’s better known as a sort of kindly philosophy professor, a persona that he lives up to in person, right down to his blue flannel shirt. In the 90 minutes I’m with him, he’s thoughtful, engaged, and prone to self-deprecation. More than once he remarks upon the allegedly frightfully messy state of his studio, exaggerating for comic effect; his housekeeper is scheduled to clean up for the party he has planned, but she’s nowhere to be found. “I just texted her,” he mutters, before we sit down. “I said, ‘Are you coming? I’m shitting bricks here!’” He’s a natural performer, in other words—and that extends to the role he plays as an interviewee: Whether talking art or politics or philosophy, everything in the world seems suddenly much more interesting in Brian Eno’s company.

With his new album Reflection, Eno picks up a thread that has run through most of his career. The soft, contemplative LP is not just ambient, but also generative—that is, it is not a composed piece of music, but rather one for which he set in place a system of musical variables and then stepped back to witness what would happen. Every combination of sound is the product of chance operations: An all-encompassing warmth, like that of cats napping in sunlit corners, is tempered by the occasional otherworldly trill, as though a highly efficient spacecraft were powering up. Every now and then, a bell rings out, breaking the meditative calm. He once used tools like magnetic tape to achieve similar effects; nowadays, his colleague Peter Chilvers codes randomization scripts that Eno drops into Logic Pro, setting in motion his cottony chain reactions.

But Reflection differs from previous generative pieces, like, 1975’s Discreet Music and 1993’s Neroli, in one important aspect: The 54-minute album is but one iteration of the piece’s virtually limitless sprawl. A corresponding iOS app, co-authored with Chilvers, will never play exactly the same thing the same way twice. Unlike the album, the app is not a recording of the piece; it is the piece itself, a virtual machine with all the probabilistic clockworks coded right in. It’s less something you listen to and more something you use to color the air around you.

It might seem like a strange time to be putting more soft, contemplative music into the world. But for Eno, who might be the closest thing contemporary pop music has to a public intellectual—he recently co-signed an open letter criticizing the British government’s overtures to Donald Trump—creating generative electronic music is, in itself, a kind of political act: a rejection of hierarchy in favor of ecological models of existence.

But ambient music represents just one facet of Eno’s boundless curiosity. I’m reminded of this after our interview, when he brings me into the music studio to show off the generative processes he used to create Reflection. Leaning against his standing desk, he flips through randomization scripts in Logic Pro, and skeletal percussion patterns suddenly explode into wild, distorted formations, more Autechre than Music for Airports.

An iTunes playlist of rough drafts contains 4412 tracks; the most recent of them, something called “Jubilant Hair Sad,” was made just the night before. “I can’t remember what it is,” he says. We listen to it for a moment: slow string pads—the kernel of an idea, maybe, but not much more. “That’s not very interesting,” he says, turning it off. Perhaps part of genius is knowing when to give up on a ho-hum idea and move on.

“I have to show you statistical guitar,” he continues, queuing up an unsteady arpeggio perforating a kind of trip-hop beat. “This tempo’s too slow to make it work,” he mutters, but then he flips a variable, and the song comes bounding to life: a wild chakka-chakka that sounds strikingly like disco’s “chicken-scratch” guitar, all created using the same randomization scripts that drive Reflection’s slowly undulating form. “I’ve always loved rhythm guitar and I’ve never been able to play it,” he beams, his inner philosopher having apparently been replaced by a much more innocent figure: tinkerer, amateur, wide-eyed thrower of dice.

Pitchfork: What are your studio habits like when making a generative piece like Reflection?

Brian Eno: I often work here in the evening. It’s when I get a bit of peace. I have speakers everywhere, so I can have three-dimensional sound. I just start something simple [in the studio]—like a couple of tones that overlay each other—and then I come back in here and do emails or write or whatever I have to do. So as I’m listening, I’ll think, It would be nice if I had more harmonics in there. So I take a few minutes to go and fix that up, and I leave it playing. Sometimes that’s all that happens, and I do my emails and then go home. But other times, it starts to sound like a piece of music. So then I start working on it.

I always try to keep this balance with ambient pieces between making them and listening to them. If you’re only in maker mode all the time, you put too much in. It was a discovery I made right in the beginning of making this kind of music, where I would make something—I was working on tape then, of course—and find that if I played it back at half-speed, it always improved it dramatically. One reason was because of the change of sonic color that you get; the thing is suddenly mellow. But the other one was that much less was happening per unit of time. That was the lesson I really took. As a maker, you tend to do too much, because you’re there with all the tools and you keep putting things in. As a listener, you’re happy with quite a lot less.

The other way I had of moving myself towards minimalism, shall we say, was when I would think at the end of a day’s work: OK, now I’m going to do the film soundtrack mix of it. As soon as you think of something as a film soundtrack, you’re thinking of something that is behind the action, that is not the action itself. And I would think, Where is this piece? It feels like evening, it’s a river, there’s vines hanging down over the water—some kind of picture would come to me. And then I would find it very easy to do quite minimal versions of things. It’s a discipline, because the path of least resistance for anyone with a lot of sound-making tools is to keep making more sounds. The path of discipline is to say: Let’s see how few we can get away with.

You equate action or effort with authorship.

That’s right. I find that you’re a completely different person as a maker than you are as a listener. That’s one of the reasons I so often leave the studio to listen to things. A lot of people never leave the studio when they’re making something, so they’re always in that maker mode, screwdriving things in—adding, adding, adding. Because it seems like the right thing to be doing in that room. But it’s when you come out that you start to hear what you like.

Given the infinite nature of the Reflection project, was it difficult to select the 54-minute chunk that became the album?

Yes, it was quite interesting doing that. When you’re running it as an ephemeral piece, you have quite different considerations. If there is something that is a bit doubtful or odd, you think, OK, that’s just in the nature of the piece and now it’s passed and we’re somewhere else. Whereas if you’re thinking of it as a record that people are going to listen to again and again, what philosophy do you take? Choose just a random amount of time? Could have done that. Just do several of them and fix them together? Is that faking it? These are very interesting philosophical questions.

Which approach did you follow?

A hybrid approach. I generated 11 pieces of the length I’d set the piece to be and I had them all in my iTunes on random shuffle, so I would be listening at night, doing other things, and as one ran through, I would think, That was a nice one, I particularly like the second half. So then I would make a note. I did this for quite a few evenings. There were two that I really liked. On one, the last 40 minutes of it were lovely, and on another, the first 25 minutes of it were really nice. So I thought, This is a studio, I’m making a record. I’ll edit them together! It was like the birth of rock’n’roll. I’m allowed to do that! It’s not cheating. It was quite a bit of jiggery-pokery to find a place I could do it, but the result is two pieces stuck together.

I find myself listening to the app differently than I would listen to an album. I might hear something, and my interpretive brain tries to ascribe meaning to that event, but then I remember it’s essentially accidental, and it defies interpretation.

It’s interesting, isn’t it? I really think that for us, who all grew up listening primarily to recorded music, we tend to forget that until about 120 years ago ephemeral experience was the only one people had. I remember reading about a huge fan of Beethoven who lived to the age of 86 [in the era before recordings], and the great triumph of his life was that he’d managed to hear the Fifth Symphony six times. That’s pretty amazing. They would have been spread over many years, so there would have been no way of reliably comparing those performances.

All of our musical experience is based on the the possibility of repetition, and of portability, so you can move music around to where you want to be, and scrutiny, because repetition allows scrutiny. You can go into something and hear it again and again. That’s really produced quite a different attitude to what is allowable in music. I always say that modern jazz wouldn’t have existed without recording, because to make improvisations sound sensible, you need to hear them again and again, so that all those little details that sound a bit random at first start to fit. You anticipate them and they seem right after a while. So in a way, the apps and the generative music are borrowing from all of the technology that has evolved in connection with recorded music and making a new kind of live, ephemeral, unfixable music. It’s a quite interesting historical moment.

Do you find it easier on the ego to release something like this instead of an album of traditionally “composed” music?

Yes, I think it is. If I make something like Reflection, people know it’s a sort of calculated, dispassionate piece of music. But if I record a song with my voice, people assume, Oh, it’s his voice, therefore it must be carrying something deep. A voice is very exposing, and of course, a voice is always seen as being the voice of the creator, no matter how many times you tell them it isn’t. A lot of singers are really trying out personalities when they sing. It isn’t them. It’s just like somebody writing a play: He isn’t the person in the play, he’s inventing personas and seeing how they interact. I think David Byrne does it; David Bowie did it a lot. Just saying, “Who do I want this character to be? What’s the world they’re in, and how are they going to behave in that world?” But of course people always read it as autobiographical. So yes, there’s much more ego tied into anything that uses your voice, essentially. Even if you try to abstract your voice wildly, people still think: Hm, that Brian—doesn’t sound too happy.

I was listening to your 1993 album Neroli and noticed that it’s in the same key as Reflection. I had them both running at the same time—the album on my laptop and the app on my phone—and it turns out they work really nicely together.

Do they! Oh, I want to try that. I often think I’ve only ever had two ideas, and I keep finding new approaches to them. And each time I do, I think, Wow, this is really new! But it actually isn’t. It’s the same idea from a different angle.

You’ve said that the difference between classical and contemporary music is the difference between architecture and gardening. Do you keep a garden yourself?

“Keep” is not quite the word. I do garden, yes, but I’m not very good at it. I’m much better at theorizing about gardening than doing it. My gardening is similar to my cricket. When I was at school I always used to think, When I get out on that field, I’m going to bash that ball all over the place. And I was nearly always out on the second ball. I had enormous confidence and very little skill. Which you could say has typified my whole career, really!

The original price of the Reflection app was around $40, which is quite a bit higher than previous apps you’ve done. Why was that? Were you trying to make a statement about value?

Yes, I was. There are two statements: One is the price and the other is that it isn’t interactive. That was quite important to me, to try to keep it free of anything you could do with it. I just did not want people sort of fiddling. I was trying to say, “This is something to listen to.” Think of it like a finished piece of music. It happens to be a finished piece of music that will never repeat, but it is a finished piece. Some people were a little bit annoyed there was nothing they could do to it. My response is: You don’t expect to be able to do anything to a CD, do you? You just put it on and turn it up.

The point about the price was that if you make a vinyl, it costs 22 pounds in England, a CD is 16. Both of those are reduced versions of the app, in the sense that they are a tiny fraction, infinitesimal, of the lifetime piece. I really want to make the point that this is an endless piece of music. And one of the ways I can make that point is to price it higher. So in England, the app went to 30 pounds. A lot of work went into it, as well. It was only the two of us, Peter and I, and it took about a year to make the app.

Last time Pitchfork interviewed you, in 2010, you said that you still listened to CDs. Is that still true?

I do. I’m much less attached to analog stuff in general than a lot of people seem to be. I think there’s quite a lot of black magic about it. For instance, I really don’t think I can tell the difference between a well-mastered CD and a well-mastered vinyl. If I’m listening to CDs for a long time, and then I put a record on, I think I notice a slight difference. Or vice versa, actually. But both ways ’round, I quite like the difference.

Do you stream music?

Not very much. But what I was just playing there [before the interview] was streamed, actually. I’ve really only started doing that recently. But I don’t listen to that much music that isn’t mine; the only problem with being a composer is you don’t get to listen to very much music. You can’t really have the radio on while you’re doing it. The people I know who are writers or painters or designers know so much more about music than me because they’re listening all the time. Those are the people I always ask about what should I be listening to. I have a friend, a social worker, and he has the most interesting musical tastes. I always say to him, “John, what’s happening right now?” He makes me CDs. Every month he gives me one. He’ll put on 25 things he thinks I’ll be interested in, and they’re nearly always things I never would have heard otherwise.

In the notes to Reflection, you write of ambient music, “I don’t think I understand what the term stands for anymore; it seems to have swollen to accommodate some quite unexpected bedfellows.” What surprises you about the way that ambient music has evolved?

It’s interesting what part of ambient they took as being the center of it. For me, the central idea was about music as a place you go to. Not a narrative, not a sequence that has some sort of teleological direction to it—verse, chorus, this, that, and the other. It’s really based on abstract expressionism: Instead of the picture being a structured perspective, where your eye is expected to go in certain directions, it’s a field, and you wander sonically over the field. And it’s a field that is deliberately devoid of personalities, because if there’s a personality there, that’s who you’ll follow. So there’s not somebody in that field leading you around; you find your own way.

In my case, because of my musical tastes, it also meant quiet and mellow. But it doesn’t have to be that; [1982’s] On Land is an example of ambient music that isn’t quiet and mellow, it’s sinister and quite dark. But mostly people took the quiet and mellow bit, which for me was just a stylistic aspect of it, not the philosophical aspect—they took that as being what ambient music is. So for me, a lot of the stuff that gets called ambient is a kind of an accidental offshoot of my taste.

Flattering, but limiting, perhaps.

Yes, that’s right. Of course, you don’t own an idea like that, and I don’t have any objection to whatever people do. But when I listen to things that are called ambient sometimes, I think, Oh, I see, it’s that part of the thing they’ve taken.

You’ve been

working on generative music for decades now. Are there any techniques today

that you see now as you did generative music 40 years ago—ideas with great

potential that people are only beginning to scratch the surface of?

I don’t think

it really is there yet, but I find some kind of idea of group composition very

promising. I don’t really know what form it will take. But there have been some

quite interesting experiments with thousands of people coordinating on the

internet to make one piece of music. To me those are more interesting in theory

than in practice so far; I may not have heard the best ones, I don’t know. It’s

an idea that I like.

“You can’t

really make apolitical art.”

BRIAN ENO

I was curious

about the album’s title, Reflection. You wrote a very

thoughtful post on New Year’s Day about the current political

moment, and I think many Americans, at least, have become more reflective since

the presidential election. Did Trump’s win come as a surprise to you?

Not to me.

About three months before the election, I wrote to all my American friends and

said, “Trump’s going to win.” I was convinced everybody was in the state of

mind we were in before Brexit. Brexit was the surprise for me. I thought, It’s

going to happen again.

Does the

current political moment change the kind of music you feel it’s necessary to

make?

It does in a

way, yes. I think that one of the interesting things that’s happened since

Trump is that everybody who isn’t a Trumpist, has become what I call a “liberal

conservative.” Suddenly, we realize that those old-fashioned institutions that

we liberals don’t think about much—like the judiciary, the infrastructure of government—are

actually worth protecting. The basis of stability in a society is in those deep

structures. So we’ve all become conservatives—and liberals as well. It’s

consolidated a lot of people who have buried differences they might otherwise

have had. That’s a new coalition. And it’s a powerful one. In that sense, the

Trumpists are much more radical than I’ve ever been. They’re Leninists,

basically.

Trump’s chief

strategist Steve Bannon even said he was a Leninist.

Fucking hell.

Christ, I got him right, then. That’s so interesting. It is the idea that you

remake society by smashing it up—but I think you just smash it up by doing

that. There’s a lot of precedents for that, where complex societies have just

fallen apart under the weight of their own complexity. It can happen! The Roman

Empire is the great example of a society that was incredibly organized,

well-run, and very successful, and in a generation disappeared. Really. One

generation. It went from the Forum being the center of global civilization to

being a place where people grazed their sheep.

And what is the

impact on art? Is there a need for political music now? Is making art itself a

political act?

Yes, I think it

is. You can’t really make apolitical art. We started out talking about ways of

composing; ways of composing are political statements. [Pulls out his pencil

and points to a diagram on his laptop.] If your concept of how something

comes into being goes from God, to composer, conductor, leader of the

orchestra, section principals, section sub-principals, rank and file, that’s a

picture of society, isn’t it? It’s a belief that things work according to that

hierarchy. That’s still how traditional armies work; the church still works

like that. Nothing else does, really. We’ve largely abandoned that as an idea

of how human affairs work. We have more sophisticated ways of looking at

things.

But to make

something is to express a belief in how things belong together. To me, that’s a

political statement. So I’m suggesting a funny mixture of bottom-up and

top-down, which is actually what I think nature does. It’s a mixture of will

and desire with an understanding of ecology—how complex things mesh together,

and how much you can interfere with that. Where do you allow freedoms and where

do you try to constrain results? That’s what I’m learning and practicing in

doing this. It is a political statement.

|

| https://www.musicradar.com/news/5-tracks-producers-need-to-hear-by-brian-eno |

If you want to talk about David Bowie, you’ll sooner or later have to talk about Brian Eno. That music producer, visual artist, technological tinkerer, and “drifting clarifier” hasn’t had a hand in all the image-shifting rock star’s work, of course, but what collaborations they’ve done rank among the most enduring items in the Bowie catalog. “I’m Afraid of Americans,” which Eno co-wrote, remains a favorite of casual and die-hard fans alike; the 1995 Eno-produced “cybernoir” concept album 1.Outside seems to draw more acclaim now than it did on its release. But for the highest monument to the meeting of Bowie and Eno’s minds, look no further than Low, and Heroes, and Lodger, which the two crafted together in the late 1970s. These albums became informally known as the “Berlin trilogy,” so named for one of the cities in which Bowie and Eno worked on them. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall during those sessions.

Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere.

Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox.

Animators the Brothers McLeod have given us just that perspective in the cartoon above. It opens in September 1976 at the Château d’Hérouville, the “northern Frenchland” studio which hosted the bulk of Low‘s recording sessions. These three and a half minutes, in which Bowie, Eno, and producer Tony Visconti lay down a couple of takes for what will become “Warszawa,” one of the album’s most memorable tracks, come loaded with gags just for the Bowie-Eno enthusiast. The cartoon Bowie (voiced uncannily by comedian Adam Buxton) sports exactly the look he did in the Man Who Fell to Earth publicity photo repurposed for Low’s cover. Eno offers Bowie a piece of ambient music, explaining that, if Bowie doesn’t like it, “I’ll use on one of my weird albums” (like Music for Bus Stops). Visconti constantly underscores his doing, as a producer, “more than people think.” And when Bowie and Eno find themselves in need of some creative inspiration, where else would they turn than to the infallible advice of Oblique Strategies — even if it advises the use of “a made-up language that sounds kind of Italian”?

via Biblioklept

| http://www.muzines.co.uk/articles/brian-eno/7300 |

In Imaginary Landscapes, documentarians Duncan Ward and Gabriella Cardazzo paint an impressionistic video portrait of Brian Eno: record producer, visual artist, collaborator with the likes of U2 and David Bowie, ambient music-inventing musician, self-proclaimed “synthesist,” early member of Roxy Music, and co-creator of the Oblique Strategies. Even if you’ve never handled an actual deck of Oblique Strategies cards — and few have — you’ve surely heard one or two of the Strategies themselves in the air: “Honor thy error as a hidden intention.” “The most important thing is the most easily forgotten.” “Do something boring.” The idea is to draw a card and follow its edict whenever you hit a creative block. This should, in theory, get you around the block, no matter what you’re trying to create. Eno first published the Oblique Strategies with painter Peter Schmidt in 1975, and here in Imaginary Landscapes, fourteen years later, you can hear him still excited about the cards’ basic premise: if you follow arbitrary rules and theoretical positions, they’ll lead you to creative decisions you never would have otherwise made.

This short documentary combines interviews of Eno with footage of him crafting sounds in his studio, simulating the echoes of a cave, say, then turning that cave into a liquid. It weaves these segments together with a trip through American cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York, then back to the Woodbridge, Suffolk of Eno’s youth, then on to Venice, one of the world’s places that draws him irresistibly with its wateriness. Place itself emerges as one of Eno’s driving concepts, not simply as a source of inspiration (though it seems to work that way for his video Mistaken Memories of Medieval Manhattan), but as a form. When Eno talks about making albums, or images, or installations, he talks about them as places for audiences to exist. In any physical place, you’re presented with a certain set of choices. You can’t always tell the deliberately designed elements from the “natural” ones, and having a rich experience demands that you actively use your own awareness. This, so Eno explains, guides how he builds “places” — imaginary landscapes, if you will — for listeners, gallerygoers, recording artists, or himself, trying to open up “the spaces between categories” and “make use of the watcher’s brain as part of the process.” Look into his more recent projects, like his iPhone apps or his collaborations with bands like Coldplay or his touring exhibition 77 Million Paintings, and you’ll find him building them still.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

|

| https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/04/arts/music/brian-eno-film-music.html |

Secret Circuits: New York’s Early Electronic Music Mavericks

In the first half of the 20th century, electronic music as we know it was in its embryonic stages. The synthesizer didn’t exist, but there were various electrical contraptions with fantastical names: Thaddeus Cahill’s Telharmonium in the early 1900s; the theremin, originally called the aetherophone, invented in 1919 by Leon Theremin; the Spharophon; the ondes martenot; the Trautonium. Yet these devices, while fascinating, were of limited usefulness.

The magnetic tape recorder, invented in Germany in the 1930s, ushered in a dramatic musical revolution. By the time tape machines started becoming more widespread in the late 1940s, artists and musicians started to realize that these machines didn’t just record – they were powerful creative tools for making new sounds. With magnetic tape, it was suddenly possible to record and manipulate sounds in ways that were unimaginable before.

But the process of making electronic music in the 1940s and 1950s – using reel-to-reel tape recorders, bulky analog test equipment and other gear – was still beyond the reach of the average person. It makes sense that electronic music’s history is often tied to famous institutions and studios, which had the space and the funding to support these sonic experiments. By the mid-1950s, there were several electronic music studios: GRM in Paris, the birthplace of musique concrète; NHK in Tokyo; and WDR in Cologne, for starters.

But an equally strange and interesting story was taking root in New York City in the 1950s, in apartments and makeshift studios. Iconolastic inventors built their own circuits, invented their own instruments and pushed the limits of tape machines, outside of the bounds of institutions and famous academic studios like New York’s Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. Four of these New York composers in particular – Raymond Scott, Tod Dockstader and Louis and Bebe Barron – were instrumental to the growth of electronic music as we know it.

Perhaps most importantly, these inventors and composers helped get electronic music into everyday life – injecting their prescient sounds into cartoons, popular movies, radio jingles and more. Instead of staying in the avant-garde, they helped make electronic music part of the fabric of the world. Many of us heard electronic music for the first time via the far-out sound effects of Looney Tunes cartoons, crafted by Scott, Dockstader and others in the 1960s. The Barrons infiltrated Hollywood, making the first fully electronic score for a movie: the hugely influential 1956 sci-fi classic Forbidden Planet. Instead of crafting their sounds within the safe cocoon of a well-funded institutional studio, they battled the whims of the marketplace – supporting themselves with their music, and often struggling to pay the rent.

Raymond Scott was born in Brooklyn, and learned a lot of what he knew about electronics from his time at Brooklyn Technical High School. Beginning in the late 1940s, Scott designed incredible machines which helped inspire the synthesizer revolution. Scott’s most famous creation was the Electronium, a gigantic “instantaneous composition-performance machine.” The analog electronic instrument was massive and impressively futuristic, like the console from a spaceship. The machine was meant to automatically generate pieces of music, much like a computer algorithm. Motown’s Berry Gordy commissioned an Electronium, the only one that still exists today (it is now in the hands of Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo).

You can also credit Scott for inventing the first sequencer. “When I first worked for him in the 1950s, he had built a sequencer with relays, motors, steppers and electronic circuits,” marveled Robert Moog, the late, legendary synthesizer inventor, who was deeply inspired by Scott. “I had never seen anything like it.”

Scott was also a successful composer; he made it big in the traditional way in the 1930s and 1940s with a pop career, which helped finance his later pioneering research in electronics. He had a flair for writing melodies you could snap your fingers to, and was in high demand for writing music for TV and radio jingles, cartoons and movies. Scott’s signature electronic sounds were created using his unique inventions, but his music never got too esoteric; he managed to retain popular appeal. You could foresee his transition to electronics early on; in his Raymond Scott Quintette recordings in the 1930s and his big-band recordings in the 1940s, it already sounded like he was waiting for the machines to take over. The tunes were catchy but rigid; he directed his band to play the melodies with exacting precision, as if he already had the concept for the sequencer in his head.

For Scott, music wasn’t really about the thrill of live improvisation; he dreamed of a future where the listener could connect directly with the composer’s vision. “Perhaps within the next hundred years, science will perfect a process of thought transference from composer to listener,” he said in 1949. “The composer will sit alone on the concert stage and merely think his idealized conception of his music. Instead of recordings of actual music sound, recordings will carry the brainwaves of the composer directly to the mind of the listener.”

Scott eventually built a deluxe electronic music studio and workshop in his grand, sprawling house on Long Island; a 1959 article in Popular Mechanics showcased Scott’s massive, futuristic setup. “The house where composer Raymond Scott, singer Dorothy Collins and their two children live in Manhasset, NY, is not a home in any ordinary sense,” Popular Mechanics proclaimed. “It is a 32-room musical labyrinth, and a testament to Scott’s electronic genius.”

Tod Dockstader was less commercially successful, and more sonically out-there. Like Scott, Dockstader also worked on sound effects for animated shows like Tom and Jerry, but Dockstader’s work tended to be less accessible and more experimental. Parts of Eight Electronic Pieces, Dockstader’s first record, were later used in the Federico Fellini film Satyricon.

Dockstader, who came from an art background, taught himself about electronic music by messing with military surplus gear and ham radios. His first edits were made in high school with a wire recorder, a primitive device capable of making lo-fi recordings on steel wire; he would make edits by holding the wire up to his face, making the splice with a burning cigarette held between his teeth.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, Dockstader was employed by Gotham Recording Studios in Manhattan. He worked on his own music in the studio at night, which eventually led to several incredible electronic music albums, including Water Music (1963) and Quatermass (1964). “I would talk to these Ampex [tape machines], they were like my friends,” he told me last year when I spoke with him for Wired. “I was always working at night, deep night.”

The story of Louis and Bebe Barron is perhaps the strangest of all, because their life story sounds like something out of a science-fiction novel. The Barrons were a husband-and-wife team who made electronic music in their apartment using an array of homemade circuits; their entire studio in the 1950s was crammed into one room of a relatively small apartment on West 8th Street in Greenwich Village.

The Barrons were most famous for creating the prescient soundtrack for the science-fiction classic Forbidden Planet, the first fully electronic film score. But the Barrons were relative outsiders; they weren’t accepted by Hollywood. Their pioneering sounds were labeled “electronic tonalities,” not music, to avoid a potential lawsuit with the Musician’s Union. “What the Musician’s Union will make of this I don’t know – but a new Hollywood movie has a score ‘played’ by no human agency,” wrote the Los Angeles Times that year. It’s hard to contemplate in 2013 how absolutely alien it must have been to make electronic music in 1956.

The Forbidden Planet score broke new ground. There had been many sci-fi movies in the 1950s that used the theremin to supply otherworldly noises, including Rocketship X-M (1950) and The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), and there were many orchestral scores punctuated with electronic sound effects. But in Forbidden Planet, there was no theremin and no orchestra – all the sounds came from the Barrons’ homemade circuitry and tape machines. There was no difference at all between the sound effects and the music. Everything – absolutely everything – was electronic.

The story of the Barrons’ strange music began with a wedding gift in 1948. A German friend gave them a Magnetophon, one of the first tape machines imported into the United States. The Barrons were fascinated with the expensive wedding gift. The tape stock was expensive too but, as the legend goes, Louis Barron had a relative that worked at 3M who could get tape stock for free. Soon they were building a makeshift home studio.

The front room of their apartment is filled with equipment. It is a jungle of electronic instruments, knobs, wires, as complex as the control panel of an airplane.

“The front room of their apartment on 8th Street is completely filled with equipment,” the author Anaïs Nin, a good friend of the Barrons, wrote in her diaries. “It is a jungle of electronic instruments, knobs, wires, as complex as the control panel of an airplane. It is separated from the living room by soundproof glass.”

In New York in the early 1950s, the Barrons quickly fell in with the avant-garde scene, working with John Cage on building up the samples for the classic 1952 work “Williams Mix.” The Barrons then created the scores for two short films directed by Ian Hugo, Nin’s first husband – Bells of Atlantis (1952) and Jazz of Lights (1954), a surreal and stunning exploration of New York City which featured Nin walking the streets with Moondog, the blind, itinerant musician who was sometimes called the Viking of Sixth Avenue. Many famous artists, musicians and writers spent time at the Barrons’ apartment in the West Village – Aldous Huxley, Nin and Maya Deren among them – and the Barrons’ lives tell a story not only of the history of electronic music, but of bohemian downtown New York in the 1950s.

The Barrons’ curious technique – giving up to the mercurial whims of the circuits, letting them dictate the way – was in stark contrast to the Paris musique concrète school and the Cologne school of composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, who favored total control over their compositions. The Barrons’ philosophy echoes what John Cage’s longtime collaborator David Tudor would say later about his own electronic music. “I don’t like to tell the machines what to do,” Tudor said in a 1984 interview. “It’s when they do something that I don’t know about, and I can help it along, then all of a sudden I know the piece is mine.”

In their own unique ways, Raymond Scott, Tod Dockstader and Louis and Bebe Barron all helped to push electronic music into the mainstream. Instead of staying within the studio, these maverick New York composers helped demonstrate that inventive, boundary-pushing electronic music would soon be embedded in our lives. They showed that you didn’t need access to a famous institution to make electronic music; you could make it yourself, in your own apartment. These pioneering do-it-yourselfers in the 1950s helped predict the future – an era where anyone can run a home studio on a laptop, where anyone can make sounds we never thought possible.

Illustrations: Kustaa Saksi

| https://www.ft.com/content/26832878-47b1-11e8-8c77-ff51caedcde6 |

INTERVIEWS, REVIEWS & RELATED ARTICLES

Sound On Sound JANUARY 1989 - by Mark Prendergast

BRIAN ENO: THOUGHTS, WORDS, MUSIC AND ART - PART 1

Earlier this year, I was lucky enough to find myself in the beautifully quaint city of Amsterdam. One quiet Sunday morning I strolled down with a friend to the 'begijnhof', a very old square. Off this lay the Amsterdam Historical Museum, which reveals to one with scale models, films, reconstructions and photographs, the entire history of the city. Inside, there were plenty of buttons to press and dials to turn as life-like miniatures lit up with the glow of population increase bulbs and growth chart meters. As we explored the many rooms and corridors of the museum, I suddenly became aware of music. At the end of a large room strewn with disturbing photographs of wartime Amsterdam, I saw a bright red flash, like a beacon revolving. As I drew nearer I noticed that things got darker here, and that underneath the beacon was a video monitor relaying a peculiar film about water. Since I couldn't understand Dutch, I sat there entranced by the flashing red light that arced around the area like a single laser show and the beautiful music that seemed familiar yet strange. I sat there for twenty minutes or more watching all these images of cascading, flowing water in slow motion, and then it clicked. In a word: Eno. In two words: How brilliant!

The music was strange because someone had mixed together segments from Music For Films (EG 1976), Music For Airports (EG 1978) and On Land (EG 1982), which unintentionally produced a completely new hybrid of these Ambient records.

The exhibition was actually about the engineering feats involved in providing adequate water drainage for a land in continuous battle with the sea. I'm sure Eno himself would be mildly amused by this application of his music, one that concurs with his personal belief in the importance of chance and novelty. I am certain that many visitors to the museum are lured to that corner by the entrancing music and hypnotic beacon, and not the subject matter, but once there cannot help but get involved. I was delighted to see one of my favourite modern recording artists undermining the preconceived notions of what music 'is' and where art 'should be'.

Earlier this year, Eno had two videos, Mistaken Memories Of Mediaeval Manhattan and Thursday Afternoon, released on PAL/VHS for popular consumption. The first arose from the accidental leaving of a video camera on his New York apartment window sill during the period 1978-1983, when he was resident there. He found that when he played back the images, the television set had to be turned on its side because the camera had been resting in that way. In a flash, the 'video painting' was discovered - a television image that was perfectly conducive to the aural quiet of his discreet music. Mistaken Memories is eighty-two minutes long and shows slowly changing skies, water towers, and the unfurling of clouds over the city rooftops.

Eno: Like the music that accompanies them, the films arise from a mixture of nostalgia and hope, and from a desire to make a quiet place for myself. They evoke in me a sense of 'what could have been' and hence generate a nostalgia for the future.

Within this brief quotation one can find the kernel to Eno's unusual approach to music and art. None of his work is finite in any way, therefore it fails to subordinate itself to the rules of industrial perfection so beloved of our Western culture. He never utilises equipment or technology for its own sake and will happily accept mistakes and malfunctions as welcome gifts. All his work attempts to define a place or atmosphere that, when heard or seen, cannot be pin-pointed in reality. Within this, one can feel a yearning for change, a hope that things might be different. In that Eno refuses to compromise his approaches or results to the will of received notions and conventions, his work can be looked on as the most radical and relevant of our time.

The second video mentioned above, Thursday Afternoon, was made in 1984 for Sony of Japan. (Their TV sets are capable of holding up to being placed on their sides better than others, apparently.) It consists of seven 'paintings' of a female nude done in San Francisco. The music that accompanied the sequence was released on CD only at sixty-one minutes - one of the first CD-only releases that took full advantage of the format. Like Music For Airports, this music revolves around small bunches of piano notes played against an ever-changing background of pure sound treatments. As the piece develops, the atmosphere takes over and the piano begins to be lost within innumerable sonic layers. The piece seems to conclude in some natural habitat, like a jungle or swamp, with very distant bird noises just being audible.

In fact, Thursday Afternoon was Eno's last solo album. Since then he has concentrated on his video work, produced U2 and, with the help of Anthea and Dominic Norman-Taylor, established Opal - a creative artists' company that gathers together old friends like Daniel Lanois, Michael Brook and Harold Budd, and investigates 'possible' musics and situations with a keen eye to the innovative.

SOUND AND LIGHT

Before we look at Opal in more detail, and consider the recent activities and thoughts of Eno, I think it important to go back to 1986 and the first proper exposition in England of his 'works constructed with sound and light'. These were video sculptures, pictures and dimmer designs that utilised the television screen as a reflective medium, around which outward refractive surfaces were built. Housed in London's spacious Riverside Studios, the objects were accompanied by semi-darkness and music not unlike that of Thursday Afternoon. This was an important testament of Eno's urge to be seen as an artist rather than a musician who just makes records or performs concerts.

The root of this particular event went back to 1983, when Eno was invited to exhibit his video paintings at the ICA in Boston with his friend Michael Chandler. Eno felt that Chandler's very small paintings in quite dark colours would not work with his own relatively bright videos. In another flash, Eno invented a totally new medium.

Eno: It is a very simple idea, and it is an idea which I think is so fascinating and so rich in possibilities, that I can't wait to see other people starting to steal it. This enables you to do something that artists have been wanting to do for many years, namely to experiment with light origins and systems of controlling light in as satisfactory a way as one can control paint or music sound... There has never been a very well developed 'light art'.

The idea of sitting in an art gallery and being surrounded by paintings that continually changed, though very slowly, was mind-boggling. The music was, as usual, just beyond the threshold of audibility and seemed to be static and changing simultaneously.

Eno: The music in these installations repeats over a very, very long time cycle; for example, sixty weeks or one hundred weeks. These are very, very long pieces of music, and they are made long by allowing several cycles to constantly run out of sync with each other. The technical problem involved was trying to make a piece of music which I would never hear and could never predict. Obviously, I have never heard this piece of music properly - maybe only for three hundred hours, but that is only perhaps for three percent of its life.

This use of chance procedure is, of course, a central theme running through Eno's entire creative life. His art college interest in La Monte Young and the tape experiments of Steve Reich, namely his 1965 piece It's Gonna Rain, are the backbone for this practice. The publication of Eno's Oblique Strategies cards in 1975, and their use on the albums Another Green World (EG 1975) and Before And After Science (EG 1977) are another case in point. Yet the fairly academic air of his interviews and discussions up to the time of the above quotes (Husets, Udstillinger; Copenhagen, January 1986) was then replaced with a more conversational and jokey style. Consider the following quote about pop video from the same session:

Eno: I am constantly fighting a battle with the commercial people that I deal with, who say to me that you have to surprise people all the time: they say that people can only watch something for three minutes. The assumption is that you're all stupid, and every few seconds somebody has to poke you with a stick to wake you up, and this is the whole theory with pop video. In many ways the only direction for pop video is to get faster and more colourful and more extravagant, and this is indeed what happens. The technical tricks get exaggerated more and more, the number of edits increase, and the girls' legs get longer and longer. There's no limit to the length of legs that seem to be appearing!

The discussion was incredibly loose as it ranged over his ideas for a quiet club which would not be geared towards somehow speeding you up, presumably with the idea of obliterating what is assumed to be an otherwise average existence; his three dimensional concept of music; nature - of which he said: I'm interested in nature and looking at it from two different angles - one cybernetics, and the other genetic evolutionary theory, and so forth. He also discussed the rhythmic quality of his pieces in detail:

Eno: These pieces have rhythm, but they are very slow. It's not just one rhythm... If you talk about rhythmic music in Africa, you never mean music with one rhythm... Nearly all African rhythms are based on two interlocking grids of rhythm and sometimes, of course, more complicated ones... I make music that is rhythmic but I have many, many rhythms, maybe twenty or thirty going on at once... I don't think rhythm in my music has disappeared but beat has, and that's a different thing.

A pretty innocuous question from the audience, regarding the apparent contrast between the rigidity of the video sculptures and the openness of his music, threw up a remarkably illuminating answer:

Eno: On my record On Land, some of the pieces are very directly based on places that I know or knew as a child, and some of the sounds on the record are attempts at imitating precise sounds of those places. For example, on one of the pieces is the river I was born next to. It was a river that always had boats on with metal masts and pieces of wire on the masts, and when the wind blew they went 'ting, ting, ting'. And there were many of these boats, always, and this was the basis of one of those pieces of music. Now those are figurative; I call that figurative music, because it is very much an attempt to paint a picture... It is an interesting thing about music, that you can relate acoustic locations... When I make this music, the first consideration is 'Where is this music?'. I think, 'Do I know where I am in terms of the music?'. The first consideration is to try to picture a place that the music puts you in... I say, 'What's the temperature in this piece?', because sound behaves differently in different temperatures. 'What's the humidity?', because sound behaves differently in different humidities. 'Is it an open place or does It have walls? Does it have a ceiling? Is the ceiling right on top or is it a long way away? Are the walls made of stone or wood, or are they some other material? Is the place stable or do I feel like I am not quite secure in it?' All of these things I can specify (in the studio) with reverberation. I can, for my own purpose, give the impression that instead of being on land I am in water, by using what I believe are quite universal psychological cues for responses... So I am working more and more in a spherative way, where I am definitely trying to make a place.

Eno went on to conclude this line of fascinating thought with: All my work aspires to the condition of painting. What I like about painters is that they stay there, they persist. I like to see a painting on the wall and I like to look at it. I can stay for as long as I want and then get on with what I am doing, then I can go back to that again and then get on with what I am doing again. So I want to make music that has that condition of being almost static but not completely so.

Some months later (March 86), Eno arrived at the Riverside Studios to showcase his new works. It was to be the occasion of his last official press conference in this country. He reiterated his views on music as 'painting' and 'location', and went into the thinking and mechanics of his video art in quite some detail. As ever, he did not confine himself to the promotional job at hand but branched out into other areas of discussion.

With regard to sound texture, he had the following to say: I think that the thing that the recording studio has offered to music, or electronics in general have offered to music, is the possibility of a tremendous expansion in the texture of instruments... People haven't generally taken advantage of the possibilities in material terms afforded by electronics... Recording in a technical sense has always developed towards some concept of fidelity.

He went on to talk of abandoning rigid formats of what a studio does or what an instrument does and that people who produce and make records do not understand that modern consumers treat records very differently to what they used to, like a piece of interior design. Again, during the course of the conference, he came back to the subject of texture, a quality of time as well as of space and objects, and with regard to cycles in music passed the humorous comment: I'm interested in the difference between cycles that, in geological terms, would be the difference between the formation of continents and the atmosphere set up by crickets!

After that, Eno was to journey to Dublin, via France, for an Irish exposition of his new objets d'art and, of course, an historic involvement with U2 that would produce the most talked about album of the '80s: The Joshua Tree.

INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC ACTIVITY

Since 1979, Eno has continually had international showings of his audio-visual work. However, as the specific exhibitions have grown in complexity, and with greater demand, his energies have recently been more directed in this way. Most of 1987 was spent in Italy doing just that. One of the most intriguing events was Monuments And Music, held in the botanical gardens, Rome, that summer. This time the sculptures were by English artist Andrew Logan and Eno provided the music.

Eno: The Italians have apparently never had difficulty understanding the interdependence of the whole continuum of artistic activity. The Orto Botanico is dedicated to palm trees - there are about fifty different varieties there - and Andrew is placing some of his larger pieces around the garden while I am making a new piece of music and a synthetic bamboo grove; hopefully complete with electronic cicadas! Later that year Eno was invited to Brazil for the Sao Paulo Biennale to show his video paintings. Music For Airports was the featured music for the event. His video art continued to be popular in Spain and America in 1988, with the latter given the benefit of a completely new display, entitled Latest Flames, which was showcased at the Exploratorium, San Francisco, last February. Yet, for all this activity, he still found time to compose music for television, work on Jon Hassell's live recordings at his own studio in Suffolk, give lectures and perform other academic duties. Interestingly, he was invited to Irvine College, California in November 1987 to address a symposium on 'Original Vision', where he discussed the processes of chance, naivety, limitations, necessity, change of emphasis and re-contexting and their importance in his work.

THE BIRTH OF OPAL

With so much going on abroad, Eno's British profile has been low in comparison, in the sense that his appearances as interviewee in the weekly music papers (a common and welcome aspect of his late '70s and early '80s work) are rare. Indeed, I cannot remember the last time he gave such an interview. Yet his presence on the scene is felt in no small way by the activities of his artistic friends and collaborators, Russell Mills, Laraaji, Harold Budd, Jon Hassell, his brother Roger, Michael Brook and Daniel Lanois, whose work is organised by the company Eno co-founded in 1984: Opal. This is run by close friends and brother and sister team Anthea and Dominic Norman-Taylor, who are wholeheartedly committed to creating a different kind of freedom for artists, one that enables outsiders and innovators to have a free hand. Starting in the Queen Elizabeth Hall in January '87 with the first Opal evening, a core group of Brook, Laraaji, Roger Eno and Harold Budd performed to a backdrop of slides/visuals/ light objects courtesy of Russell Mills and Brian Eno. This show went on to tour extensively in Spain. Since then Opal has championed collaborations, performances and new perspectives on music both from its own artists' point of view and those of the public. It regularly contributes to the Echoes From The Cross project which, since 1986, has been performed annually as a diverse concert in order to preserve the nineteenth century Gothic church of St. Peter's, in Vauxhall, and enhance its heritage. In fact, the performances which mix several styles of music with a contribution from one or more Opal artists take place within the church itself. Last March, I had the pleasure of hearing Eno's Planet Dawn (an old but unpublished piece) performed by a chamber ensemble. Recently, Opal has launched its own record label Land Records - with four releases from Roger Eno: Between Tides - a neo-classical ambient work that draws on Erik Satie and minimalism; Harold Budd: The White Arcades - a further exploration of slow motion flux and astral melody from the American keyboard maestro; Hugo Largo: Drum - an American post-punk rock combo with the accent on theatricality and atmosphere; and the combination Music For Films III, which includes new pieces by Eno, Lanois, et al, plus many surprises.

In April this year, Opal was responsible for the first ever satellite TV link between Russia and the West with rock music as its subject. Hosted by Eno, with Peter Gabriel, Chrissie Hynde, Paul McGuinness (U2 management) and Mark Cox (of underground group The Wolfgang Press) as panel guests, an important cultural bond was made with the 'unofficial' hard-core rock situation in the USSR. With entrees into other fields, Opal is quite a unique little organisation. I spoke to Anthea and Dominic Norman-Taylor about how the company came about and its vision for the future.

Soft spoken and quietly mannered English, Dominic came over two years ago from Japan to join his sister in running Opal. There he had worked in advertising and was involved in managing a young female singer keen on having a Western audience.

Opal was set up by Anthea and Brian back in 1984, after they both decided to leave EG Records. Land Records only really came into being at the beginning of this year. As you know, we were with EG and Virgin and, with all due respect to them, it didn't really work out terribly well. We were frustrated with not really having the kind of freedom we thought we should have got. Also, the way sales were going, and a number of things like that. It really didn't seem like a very good marriage. After going around to another couple of labels we thought it was going to be much of a muchness, so we said we'd go it alone in the UK. I know it has only been going a few months but, thankfully, we haven't looked back since.

Chatting to Dominic in the airy offices of Opal Ltd in Harrow Road one summer's evening some months back, we cover much ground on the ins-and-outs of running a record/management company with little or no experience. One sensitive point I bring up is the accusations of 'benign nepotism' that are often insinuated by writers and critics at Eno's collaborations. The position of his brother Roger has always been looked on suspiciously by the so-called experts, even though he's a classically trained composer with a background in therapeutic aid and now two great albums to his credit, Voices (EG 1985) and the new record Between Tides.

Dominic: Well it's the kind of attitude 'Oh ! Here's an interesting little record from Brian's younger brother.' It's a problem, yes. I mean, Brian doesn't like it that much himself. It would be stupid to try and pretend it doesn't exist. It's very tricky.

Q: I've never heard any of this music on the radio. Jon Hassell's last collaboration with Eno, Power Spot (ECM 1986), would have been perfect for Radio 3 or any of the less restricted independent stations here. But alas, as ever, one cannot hear such great stuff on British airwaves.

Dominic: No, not in this country. In Europe and America I believe it's much better because, especially in the US, the university and local radio stations are particularly sympathetic. It's just seen as alternative music there, non pop stuff. In Germany I've heard our stuff quite often. Unfortunately, it just seems that radio in this country just always wants to play pop music.

During the course of the conversation Dominic admits an interesting fact in relation to the lack of widespread knowledge and acclaim in England for Eno's audio-visual experiments: No one really reviewed the Riverside installation. To be quite honest, I don't think that many people in this country know who Eno is. Certainly, people are far more aware of the name in places like Spain, Italy, Germany, Japan or America. Also, in response to a question relating to the 'intellectual listener' tag that this music often receives: I honestly think it appeals to all sorts of people. Some writers have an image in their head of what kind of people listen to this music. Someone said to me the other day that they were in a taxi with some cabbie, and he started going on about Jon Hassell and Harold Budd! Imagine this old cabbie trundling along in his car, and for some reason he said 'Oi ! I roilly loike Jon 'assell and 'arold Budd.' I honestly think it could be anybody who likes it. I mean, before I joined Opal I used to listen to mainstream pop and classical.

Where Dominic is outwardly subdued about Opal and its role in creating something new in British and world music/art, his sister Anthea is more livid and enthusiastic about the whole thing. I'm sure this arises from the fact that for two years she was doing it all herself and now, when everything is coming together in a big way, she is happy to be addressed questions. As one of the few women working in the record and management side of the music business, she deserves a lot of credit, particularly for her wile and acumen in approaching things obliquely and achieving much success. I spoke to her some days later at her Chelsea flat.

Q: According to Dominic you worked at EG Records. Is that where you got most of your experience?

Anthea: Everything seems to happen by chance, I think. I joined EG in 1974 and left in '83. When I got the job I didn't have any real qualifications at all. I was quite young at the time and short of money, and needed some temporary work. I had no secretarial experience but did have a background in science, so maths was no problem to me, and therefore I was given the job of sorting out the royalties, since EG was quite new in those days, you know. There was such a lot to do that they ended up giving me a permanent job as 'royalties clerk'. I really enjoyed doing that and I got on really well with them, so l became 'copyright manager' and eventually a director of the company.

As the years went by, Eno formed a very healthy relationship with Anthea with regard to his creative ambitions and musical output. Feeling that the EG situation had run its course, they both left in 1983.

Anthea: Brian and I decided to set up a company together at the beginning of 1983. From the beginning it was very clear that it was to be an artists' company. Within many conventional record companies, the relationship between the artist and the organisation is one of bank manager and client. What mattered to me was the mutual relationship, of like being more of a servant to the artist. Like the artist has got the ideas and is the creative one, and I'm good at administration but need a good artist to look after. So Brian was very happy for me to do that but also wanted all his friends to have the same benefit. Then it quickly spread to other artists - and that's the basis of Opal.

Q: Opal and Land Records are not necessarily Brian's sole creation. It's more of a team effort, isn't it?

Anthea: Well, it's easy to have a phrase that says it's so-and-so's label. You get this with Sting or Stewart Copeland, and even Phil Manzanera. Well, with Sting's Pangaea project he's helping to release all kinds of music that interests him, and therefore he's obviously doing a label. With Land it is much more a bonafide label, whereby all the artists on it are equal contributors to the total image. The group Hugo Largo came up with a good expression for Brian's role, which is 'curator' - and that's a nice image. It's like a museum which has a collection. It doesn't mean he owns it, but he decides 'Well, we'll have this rather than that.' He gives artistic guidance, certainly, while myself and Dominic have a large artistic input as well.

Q: Is the music on Land at present, and will it be in the future, a specific stylisation of 'new music'?

Anthea: We absolutely want to be the opposite of that. There are so many different things going on in so many areas that are interesting, and it's quite funny that most of the demo tapes we get seem to be imitative of what Opal artists have done already. People assume that having done one thing that you want more of it. The last thing we want is more Ambient stuff. Yes, there should be some sort of unifying thing to the music something that, say, could be called a frontier in mentality. What I hope is that the things we get involved in are not self indulgent. The recipient of the work we put out should be getting a good deal.

Q: What about your market? Is it quite defined or is this music for everybody and anybody?

Anthea: Well, I wouldn't like to say it's for anybody, because that would be insulting to the people who buy it. But I don't think it has to be so specialised. There are markets out there that haven't been explored, and one of them say, with Harold Budd's music is women. Up to now, the female record buyer has been perceived in two categories: the teenyboppers and the housewives. Women, as buyers, are categorised by record companies as frivolous buyers of music only. They don't really think of women like me, and there are lots more like me.

MUSICAL IDENTITIES

Moving on to the music itself, the first Land LP is Roger Eno's Between Tides, a superlative work of great beauty which fuses the chamber music tradition of classical acoustic music with precision piano playing that draws on equal levels from Erik Satie and Brian Eno's earlier work, particularly 1975's Another Green World, from which the track Between Tides itself quotes. Despite his obvious talent, Roger is considered by the unenlightened to be a closed book; a dark fish that swims in the wake of his brother's more famous achievements. This is a silly notion that Anthea is quick to dispel.

Anthea: Though Roger has got the musical training, it is a fact that he's more melodically gifted than Brian. Roger is a born musician. It's not so much his training but you can take Roger, sit him at a piano, and he'll turn out a tune. He's genuinely musical, with melody flowing right through him. He's constantly writing new pieces of music and being quite prolific. He studied at Colchester Institute - in fact it was the euphonium - and though he can read and write music and all that, he is not an academician. He's eleven years younger than Brian, who has just turned forty, so they hardly knew each other as they grew up. Yet there's a musical thing in the family. They've got two sisters who've got lovely voices and are musical, but they've not utilised their talents in that direction. Neither of their parents were directly involved in music but, a generation before, their grandfather was quite musical in that he made organs. And an uncle was in a brass band in Germany - or something like that. What's good about Roger is that it's always good to hear his music first and then meet him, because it's such a surprise. From his music he sounds like a sort of 'classical' composer, but in reality he's the biggest lunatic you'll ever meet! He could be a stand-up comedian.

Q: Does he teach or play with orchestras?

Anthea: Not much. He lives a very simple life and his only source of income is the few record's he's done and the few film scores. Every now and then he's done a performance for some theatre or something like that. You see, his ability is hard to categorise, in that it's not conventional in the 'classical' sense of the word but he's using those acoustic instruments. He quite dislikes electronic means, though he can turn out a song or tune in virtually any style. But he's got quite a traditional streak in him, a little bit old-fashioned in a way.

Harold Budd's new LP, The White Arcades, is a fascinating extension of the 'sound painting' techniques explored on 1986's Lovely Thunder and The Moon & The Melodies with The Cocteau Twins. To my mind, it's his best record to date. The thunder rolls are ever present but are now subsumed to indefinable piano and synthesizer textures. Though Brian Eno is involved on The Real Dream Of Sails and Totems Of The Red Sleeved Warrior, it is on a small scale, especially on the glorious miniature The Kiss, that Budd's genius for understanding the potential of piano timbre shines through. Now resident in England, Anthea sketches in some more details.

Anthea: Harold recorded that all on his own in Palladium Studios, Edinburgh. That's the sort of Cocteau Twins connection, in that it's a place they've recorded in a lot. He's still friends with them, and one day was talking about some recording he'd like to do, and they just went ahead and booked the studio for him. Robin Guthrie was involved on one track and Brian did some treatments and engineering on two others. The album was still mainly recorded at Palladium, then a bit at The Cocteau's own studio, and the rest at Brian's Wilderness Studios in Suffolk. Really, Harold is quite a lonesome man in that he has and does mostly work on his own.

BRIAN ENO: THOUGHTS, WORDS, MUSIC AND ART - PART 2 / Sound On Sound FEBRUARY 1989

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p033smwp#mp3

Brian Eno's BBC Music John Peel Lecture 2015

http://www.openculture.com/2012/05/how_david_byrne_and_brian_eno_make_music_together.html

How David Byrne and Brian Eno Make Music Together: A Short Documentary

On Monday, we posted the Artist Series, short profiles of various aesthetically-oriented creators by the late Hillman Curtis. Today, please enjoy what feels like the jewel in the Artist Series’ crown, despite not officially being part of it: Curtis’ promotional documentary on Brian Eno and David Byrne and their collaboration on 2008’s Everything That Happens Happen Will Happen Today.

Curtis interviews Eno and Byrne in their separate workspaces, captures their conversations about parts of their songs, and even — presumably in keeping with the album’s do-it-yourself promotional spirit — lets them photograph one another. He also shows them doing what they do best when not creating: cycling, of course, in Byrne’s case, and looking pensively through windows in Eno’s.

In none of these nine minutes do Byrne or Eno perform anything. Curtis doesn’t need them to; he taps instead into the combination of articulacy, clarity, and idiosyncrasy that has earned them nearly forty years of status as cerebral popular music icons. Just as the early eighties’ nascent sampling technology gave Byrne and Eno a new framework with which to think about music when they recorded My Life in the Bush of Ghosts together, the ability to send sounds over the internet and extensively modify absolutely any recording after the fact shaped the construction of Everything That Happens Will Happen Today.