|

| https://clockshop.org/project/about-octavia-e-butler/ |

A Sense of Doubt blog post #2311 - OCTAVIA BUTLER IS VERY POPULAR RIGHT NOW

This is such an incredible listen. 🙌 #Octaviatriedtotellus https://t.co/aQl6RfIjYn

— Meredith Irby (@mereirby) February 20, 2021

https://slate.com/culture/2020/09/octavia-butler-parable-of-the-sower-talents-pandemic.html

Why So Many Readers Are Turning to Octavia Butler’s Apocalypse Fiction Right Now

|

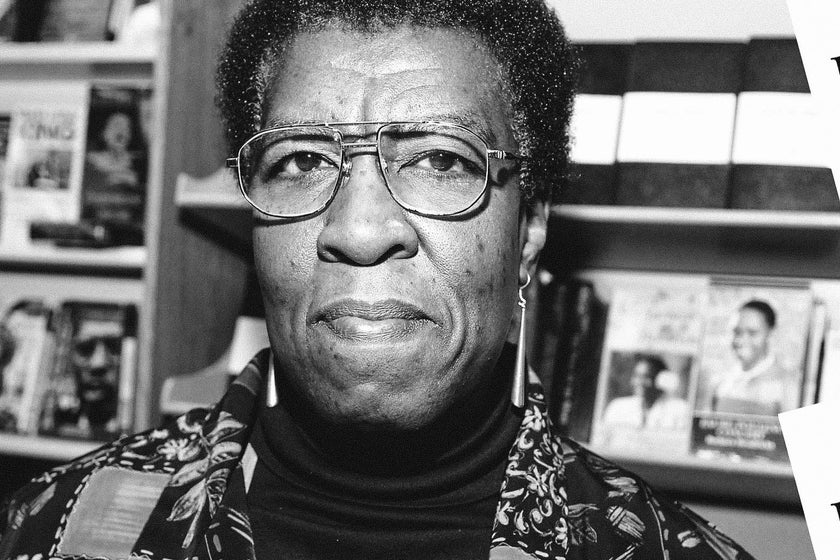

| Octavia E. Butler. Malcolm Ali/WireImage |

Earlier this month, Octavia Butler’s novel Parable of the Sower made it onto the New York Times’ bestseller lists 27 years after its original publication. The book, one of two in a planned trilogy that was never completed, follows Lauren Oya Olamina, a Black teenager who lives in an environmentally decayed and socially chaotic California in the 2020s—at the time, still a distant, futuristic decade. In Parable of the Sower and Butler’s 1998 follow-up, Parable of the Talents, Olamina leaves the gated compound where she grew up, goes on the road, starts (and loses) her own community, and becomes a leader of people, spreading a set of ideas she calls “Earthseed.”

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents contain many plot elements that seem to have “predicted” our current circumstances. But because Olamina’s story is also the story of a prophet—and because Butler is interested in how people might retain their humanity and direction through conditions of extreme chaos and change—the Earthseed books are instructional in a way that other apocalypse fictions are not. They are not prepper fiction, though reading them will teach you a thing or two about go bags and the importance of posting a night watch. According to people who love the books, myself included, they offer something beyond practical preparations: a blueprint for adjusting to uncertainty.

During this isolated, anxious spring and summer, projects centered on the Earthseed books have sprung up across the internet. Scholar and minister Monica Coleman and Afrofuturist author Tananarive Due have been hosting monthly webinars called Octavia Tried to Tell Us. (There’s a hashtag, applying the motto to everything from the California wildfires to the president’s many failures in leadership; you can also buy merch with this slogan on it.) There’s another group reading Butler’s entire body of work, starting this month with plans to continue through November 2022, that can be found at the Twitter handle @OebRead. And a graphic novel adaptation of Parable of the Sower, illustrated by Damian Duffy and John Jennings, came out in January—a fortuitous publication date for work that was clearly in motion before the pandemic changed everything.

But my favorite part of the Octavia Butler resurgence might just be Octavia’s Parables, a podcast by musician Toshi Reagon and activist Adrienne Maree Brown and a chapter-by-chapter read of both Earthseed books. The podcast, which also features music from the Parable of the Sower opera that Reagon co-wrote with her mother, Bernice Johnson Reagon, has become a cathartic must-listen for me this summer. The hosts begin every episode with a song from that opera, tapping a foundational Earthseed verse for its lyrics: “All that you touch you change/ All that you change changes you/ The only lasting truth is change/ God is Change.” Its tune now comes into my mind whenever I begin to panic (which is about 40 times a day).

Butler’s books resonate right now because the apocalypse they describe is not singular but a series of them. There’s no major event that wracks the United States, just an accumulation of serious problems (climate change, inequality), and second-order crises (hunger, war, an epidemic of abuse of dangerous designer drugs). Part of Parable of the Talents is narrated by Taylor Bankole, a physician Olamina meets on the road, who eventually becomes her lover. Bankole describes the period known as “the Pox” (short for “apocalypse”) as “a decade and a half of chaos”—though Bankole, writing a few years after its supposed end, thinks the Pox was much longer than that.

“I have read that the Pox was caused by accidentally coinciding climactic, economic, and sociological crises,” Bankole writes. “It would be more honest to say that the Pox was caused by our own refusal to deal with obvious problems in those areas. We caused the problems: then we sat and watched as they grew into crises.” This passage is a contender for “the most 2020 thing,” with another set of sentences from the Bankole section as a close runner-up: “The United States of America suffered a major nonmilitary defeat. It lost no important war, yet it did not survive the Pox. Perhaps it simply lost sight of what it once intended to be, then blundered aimlessly until it exhausted itself.”

In certain other fictional apocalypses, an electromagnetic pulse or an outbreak of zombie-ism can serve as a leveler that raises somebody humble, like Glenn the pizza deliveryman, up to the status of hero. In the Earthseed books, as in our own America, the suffering is always unequally distributed. Part of the horror lies in seeing the way the middle- and upper-class characters turn their backs on the poor completely. In Olamina’s Southern California, among the many homeless people who live outside the walls of her compound, the worst kinds of rape, abuse, suffering, and disease are rampant. (The police must be paid by citizens to do their jobs, and so they do nothing about any of this.) The people who must live outside toss “gifts of envy and hate”—dead animals, “a bag of shit,” “even an occasional severed human limb or a dead child”—over the walls.

That image—a dead child as message, the ultimate expression of hopelessness and bitter anger—has stayed with me since the first time I read Sower. Broken children and broken childhood are an omnipresent theme in both books. Because of the chaos of the Pox, child labor has returned; child slavery (including child sex slavery) is rampant; education is “no longer free, but still mandatory according to the law.” “The problem was,” wrote Olamina’s daughter Larkin in another part of Talents, “no one was enforcing such laws, just as no one was protecting child laborers.”

Talents, especially, is packed with trauma. A few years after Olamina leaves her home compound and goes on the road, the town that she founds in the mountains in Northern California with fellow Earthseed believers, a settlement called Acorn, is thriving. About 60 members of her racially and ethnically diverse group are cooperating in group living, each member beginning to specialize in a trade or skill that they enjoy and that benefits the community. The children go to a community school; everybody slowly heals from earlier traumas. Then, a paramilitary group associated with an ascendant Christian church takes over the town, enslaving its citizens with the help of collars that are capable of inflicting pain if the wearer tries to escape or displeases the person who’s controlling the tech. And Acorn’s children are taken away, adopted out into “good Christian” families. (Octavia tried to tell us …)

Since becoming a parent and getting a bit older and more fearful, and since times have gotten worse in our real-life United States, rereading these books has newly confronted me—made me see that I have the same fears that make most middle-class, fearful-of-falling people in Olamina’s California draw inward and build up walls, trying to pretend that they can single-handedly protect what they love most. That’s one reaction these books provoke: a turning away, a turning in

“When I first went to read these books, I read a few pages and couldn’t go on,” Toshi Reagon told me in an interview. “But I was getting ready to do a workshop with my mom and Toni Morrison at Princeton, in 1997, and so I had to read it. And once I read it, I couldn’t put it down.” When I ask her about the weird mix of grimness and hopefulness in these books, Reagon points out the members of Earthseed largely survive their enslavement with their commitment to one another intact. The pain is real, but they remain, as she put it, “generous” to one another, considerate of one another’s needs, even when they’re emotionally devastated. “You’re alive,” Reagon said. “You have your skill set, you have your community, in whatever way that is. And something happens, and because of who you are, and what you know, you figure out survival. If you’re still alive, you’re still breathing, you take a next step.”

Olamina writes, in one Earthseed verse:

God is Change,

and in the end,

God prevails.

But meanwhile …

Kindness eases Change.

Love quiets fear.

And a sweet and powerful

Positive obsession

Blunts pain,

Diverts rage,

And engages each of us

In the greatest,

The most intense

Of our chosen struggles.

For Olamina, that “sweet and powerful positive obsession” was “living among the stars”—a space colony, an idea that, as Reagon pointed out when I asked her about it, was very “of the time” when Butler was writing. “She says, ‘Humanity needs to live among the stars,’ ” Reagon said. “I’m like, ‘We already do.’ We live on this one planet where we can breathe the air, drink the fresh water. This planet is for us.”

You don’t have to believe in space colonization, I don’t think, to believe in the idea of Earthseed. Any “sweet and powerful positive obsession” will do. And if there was ever a time to develop one, it’s now.

Seven Times Science Fiction Got Genetic Engineering Right

FX Is Adapting Octavia Butler’s Kindred

NASA Honors Octavia Butler With Martian Landing Site

Symphony Space Presents an All-Star Celebration of Octavia Butler

Ten Eco-Fiction Novels Worth Discussing

Seven Vampire Reading Recommendations for Fans of What We Do in the Shadows

THE LOVECRAFT REREAD

Love in the Time of Parasitic Breeding Strategies: Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild”

A New Podcast Will Take a Deep Dive Into Octavia Butler’s Parable Novels

The Thing With Wings: Fledgling by Octavia E. Butler

Grandmother Paradox: Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

An Earth(seed) Day Parable: Livestream an Operatic Version of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower

Books That Grab You

Library of America to Publish the Works of Octavia Butler

Octavia Butler’s Dawn Revived for Amazon Studios by Ava DuVernay and Victoria Mahoney

Subterranean Press Announces Two Beautiful New Octavia Butler and Neal Stephenson Editions

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2106.16 - 10:10

- Days ago = 2175 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment