A Sense of Doubt blog post #1943 - How many bad apples in the police pie? HODGE PODGE 2006.14

I am still on that narrative being promoted by so many including that person who believes himself to be President of America that 99% of police officers are good and only 1% are "bad apples."

The long history and the current examples of police brutality DO NOT bear out those statistics as true.

Furthermore, as so many African-Americans speak out about being afraid of police just during a "routine" traffic stop, that fear, and for some PTSD, cannot be caused by just 1% of the nation's police.

Granted there good cops. I am not arguing that the ratio is 99% bad and 1% good apples, though some would as they see so much brutality and corruption among police (just take a few minutes to see what sex workers are writing about that online or go actually speak to a sex worker) that they would argue for that ratio.

But what is the ratio? How many cops abuse their authority regularly? How many use excessive if not deadly force when it is not necessary? I am aware that these police officers put their lives on the line all the time against the threat of "criminals" and "violent offenders," of whom we are told to be afraid. Some of the fear is real, but how much? Many questions to pose and yet the answers may be hard to come by.

But what is the ratio? How many cops abuse their authority regularly? How many use excessive if not deadly force when it is not necessary? I am aware that these police officers put their lives on the line all the time against the threat of "criminals" and "violent offenders," of whom we are told to be afraid. Some of the fear is real, but how much? Many questions to pose and yet the answers may be hard to come by.And yet, Seattle leads the way (as it often does) with the "free" zones, the "autonomous" zones, areas in which the police have been asked to leave and have complied.

https://www.seattlepi.com/seattlenews/article/In-the-new-Capitol-Hill-Autonomous-Zone-15330353.php

and

https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/capitol-hill-autonomous-zone-becomes-political-flashpoint-as-durkan-rebukes-trumps-message-to-take-back-city/

Standing on a ladder next to the Seattle Police Department's East precinct, a person wearing a yellow construction helmet on Tuesday hung a new sign to the now boarded up building marking the day after Seattle Police left the area. "This space is now property of the Seattle People," the sign read in large red letters on black canvas. A green sign now hangs next to it, welcoming people to the newly coined "Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone."

Jeremy Vajko had his van stationed inside the zone where he invited protesters to write phrases or draw pictures. The silver van was was covered with words written with different colored markers, reading "We stand in solidarity," "Keep going do not get weary" and "Silence is complacency." Some people drew flowers, too, to symbolize those who had died.

It all started, Vajko said, when he put tape on the back of the van to say the words "Y U Here." Then, he brought markers so people could share. It just evolved from there, Vajko, who's been out at the protests mostly every day, said.

And in the center next to the precinct, people stood in a circle as they shared their stories, experiences and demands. Many people talked about being out on the frontlines of the protests every single night, facing tear gas and flashbangs from Seattle police. Several people listed specific changes they're fighting for, such as defunding the Seattle Police Department and reinvesting money in community programs. People talked about what come's next, how they plan to move the movement forward.

People also shared personal experiences and what it will take to get the change they're demanding.

The environment, once tense, seemed calmer. But people still kept that sense of urgency.

A man who identified himself as Hauser, said he's been out every day, and has seen a "coming together of people and community" that he's never experienced before.

"It felt like there was way more unity than I've ever seen in any protest," he said, adding he grew up in Seattle going to protests every year. "This isn't new, but this kind of protest, it feels different."

Hauser said every day over the past several days, he’d seen people peacefully protesting, faced with extensive police force.

"Its all love on one side and just hardcore lines of police brutality," he said. "They would literally incite people to get angry.”

Now, in the zone, he’s seeing people debating and talking about actual issues. Everybody is given the opportunity to share, he said and for their voices to be heard.

“Not everybody agrees but we all agree there is an issue here that we can't stand around and be silent,” he said. “Because people are very supportive and open and they’re willing to discuss and debate and they’re willing to grow.”

He said he's never seen what's happening in Capitol Hill anywhere else.

If only the whole world could be like this magical place in Seattle. Maybe it's ephemeral. Maybe it won't last. Or maybe this place shows a glimpse of what life can be like in the future if we free ourselves from the totalitarian police state meant to "protect and serve" that has been exposed for what it has been for much of its existence: to oppress, brutalize, and exterminate violently without due oversight or recourse for its victims.

Enough.

People do not want to live in fear, and maybe the path to success is less authority not more.

Surely, this philosophy has proven true during the protests so far. The more force the police attempt to use with protestors the more escalated they become and thus violent. When police de-escalated, joined the protesters in kneeling in solidarity, or even abandoned the streets, precincts, protest arenas, violence subsided dramatically.

And yet, this "president" wants to be a "law and order" leader and "dominate the streets," which he has since re-framed as the nonsensical "dominate with compassion," whatever the fuck that means.

Welcome to this week's hodge podge. A big collection of things this week from the aftermath of George Floyd's murder and those in the streets for BLACK LIVES MATTER (because now Atlanta is facing another situation after a shooting Friday night) as well as the usual politics, pandemic update (yes, there's still a pandemic), some cool art and comics, some intriguing science and space news, some disturbing news of the Chinese spreading misinformation via Twitter, and much more.

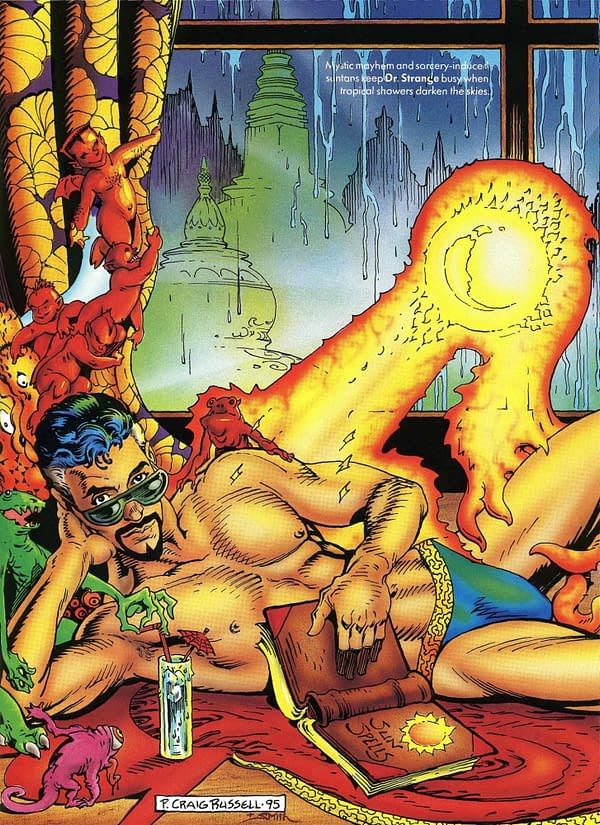

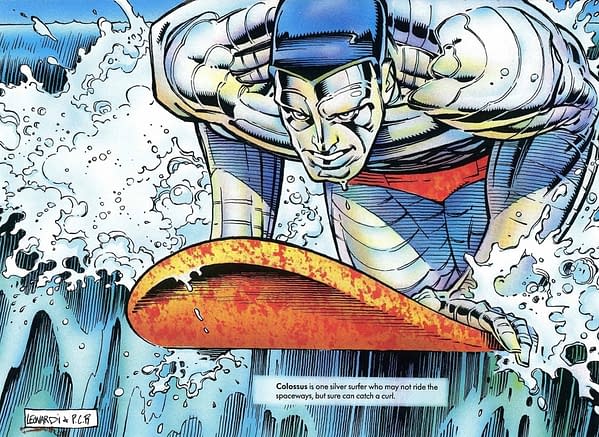

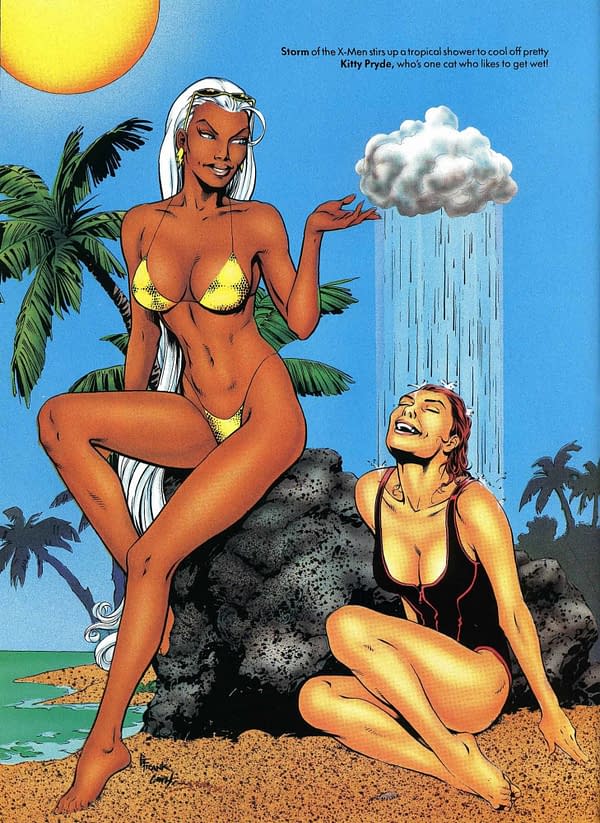

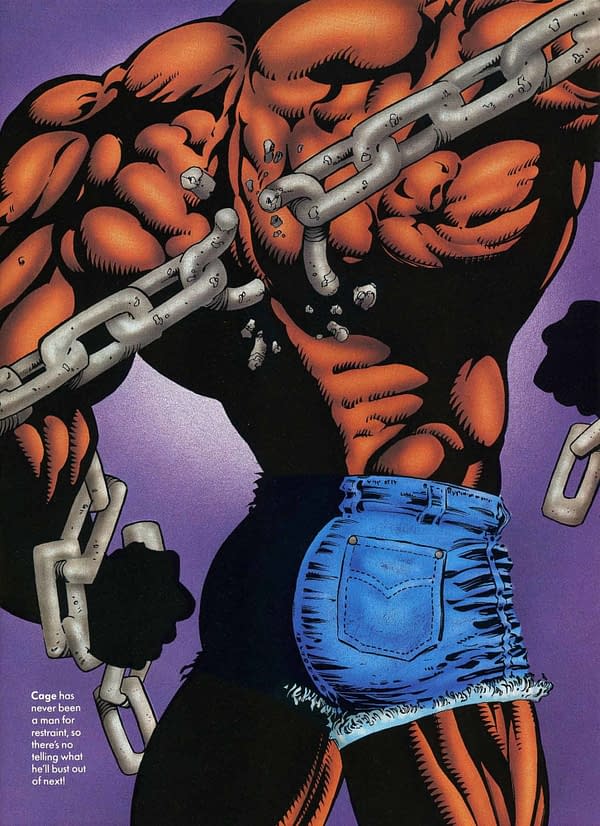

There's some VERY GAY comic book art, Bandcamp's announcement to donate 100% of its revenue on June 19th (Juneteenth) to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, tons of great Twitter posts and others that are outrageous (Thank you DT), mysterious structures deep in the earth, new earth-like planets, Titan migrating away from Saturn faster, jailbreaking the STUPID DRM in GE's refrigerator, what DEFUNDING the police means, and some great art by AFRICAN-AMERICANS. All this and still many things I did not mention in today's gallimaufry stew of yumminess. Oh and some stuff about sports...

But first, this point about how much worse it can get... which is worse and worse...

I don't think it can get worse with this "person" who has managed to take over in the White House, and then it does get worse. And in getting worse, it makes my effort to sound reasonable and not use invective like name calling to respond.

Donald Trump's deeply irresponsible conspiracy theory on the Buffalo man injured by police

https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/09/politics/donald-trump-martin-gugino-antifa-tweet/index.html

An elderly man approaches a police line in Buffalo, New York. He is pushed backward by police, stumbles and falls, hitting his head on the pavement. Blood immediately begins to pour from his ear. None of the officers stop to help him.

In a country on high alert for incidents of unnecessary use of force by police against those protesting in the wake of the death of George Floyd, the video sparked outrage. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo called the episode "wholly unjustified and utterly disgraceful." The two officers involved in the incident were suspended.

But on Tuesday morning, the President of the United States suggested -- without offering a shred of evidence -- that the entire episode was the result of a broad scam involving Antifa, a protest organization "whose political beliefs lean toward the left -- often the far left -- but do not conform with the Democratic Party platform."

Trump 'will not even consider' renaming Army bases named for Confederate leaders

https://thehill.com/policy/defense/502115-trump-will-not-even-consider-renaming-army-bases-named-for-confederate-leaders

President Trump said Wednesday he "will not even consider" renaming Army bases that were named for Confederate military leaders after top Pentagon officials indicated recently they are open to the idea.

In a series of tweets, Trump argued the bases have become part of U.S. history and should not be "tampered with."

"These Monumental and very Powerful Bases have become part of a Great American Heritage, and a history of Winning, Victory, and Freedom," he tweeted, adding that "HEROES" who won two world wars were trained on the "Hallowed Grounds" of the bases.

...history of Winning, Victory, and Freedom. The United States of America trained and deployed our HEROES on these Hallowed Grounds, and won two World Wars. Therefore, my Administration will not even consider the renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations...— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 10, 2020

On Friday, the Marine Corps issued guidance banning public displays of the flag, including on clothing, mugs, posters and bumper stickers, following up on Commandant Gen. David Berger’s February commitment to do so.

On Tuesday, the Navy followed suit by announcing it too would ban the flag on bases and ships.

WEEKLY PANDEMIC REPORT

Anyway, as usual, here's the weekly links to the data about cases (lower than reality) and deaths (lower than reality, also) due to COVID-19.

Data can be found here, as always:

This is also a good data site:

Fox News is basically the Klan with more visible hair.

Here's two REALLY good reasons not to watch FOX NEWS and not to give it credit for much of anything other than being a propaganda tool for white supremacy:

https://www.wonkette.com/tucker-carlson-brutally-attacked-by-muppet

That's it. That's what made Tucker Carlson mad. Muppets saying black people are treated unfairly in America. This is what he is reacting to. That is the entire exchange he showed, in order to show Cracker Barrel America the thing they are supposed to be outraged about.

https://www.wonkette.com/tucker-carlson-heard-about-some-boobies-and-it-made-him-mad

Tucker Carlson heard about some boobies and they made him mad. None of this is surprising.

He's also had a pretty bad week, so drink to that later. Advertisers are fleeing after he declared on Monday night that the Black Lives Matter movement isn't even about black lives, and he considers this evidence that "the mob" is coming after him and trying to silence him. As the New York Times reports, advertisers like Disney, T-Mobile, Poshmark and even Papa John's are running for the hills, because surprise, most companies don't want to be associated with white nationalists right now, and Tucker Carlson is a white nationalist. This is on top of all the other advertisers Tucker's lost over the years, because he's a white nationalist.

Basically the only commercials you see if you actually watch Tucker on the Fox News network are for My Pillow

https://www.wonkette.com/tucker-carlson-black-lives-matter-not-even-about-black-lives-laura-ingraham-maybe-its-about-gays

TUCKER CARLSON: No matter what they tell you, it has very little to do with Black lives. If only it did. If Democratic leaders cared about saving the lives of Black people, and they should, they wouldn't ignore the murder of thousands of young Black men in their cities every year. They wouldn't put abortion clinics in Black neighborhoods. They would, instead, do their very best to improve the public schools and to encourage intact families which we know beyond a shadow of a doubt is central to the life prospects of children. They'd try to make Black neighborhoods as safe as their own neighborhoods. They would close the payday lenders that add so much misery to the lives of poor people of all colors.

You know, the stuff white Republican racists think is best for black people, a subject about which they have many opinions. If only somebody would listen to white Republicans, then black people would be saved! Plus ... payday lenders, a thing we have just learned Tucker Carlson has even said before. Congratulations on being right on one thing, Tuck!

Bonus points for invoking the wingnut fundamentalist Christian lie that abortion is black genocide, because we all know forcing women to carry pregnancies to term so that white Republicans can deny them healthcare and housing works out way better, for black people.

CARLSON: But they don't even consider doing any of this, they don't even try. Instead, they encourage theft and mayhem as if that will help. It will not help.

This may be a lot of things, this moment we're living through, but it is definitely not about Black lives. And remember that when they come for you and at this rate, they will.

Major League Baseball Players Association Executive Director Tony Clark today released the following statement: pic.twitter.com/d1p3Oj4K70— MLBPA Communications (@MLBPA_News) June 13, 2020

Since David Bowie is trending now’s a good time to remind people that he publicly ridiculed MTV for not playing black artists on their program as much as white artists.https://t.co/vbPVZwcQMO #DavidBowie— GamelinkReviews (@GamelinkReviews) June 9, 2020

With Stan Lee trending, I think it’s an appropriate time to share this opinion piece Stan wrote up in 1968, which only seems more relevant now. pic.twitter.com/gRvJVX4JMx— White Widow Super 🧀 (@WillLickboi) June 9, 2020

One thing you would change about the world?— Sílvia (@JustMe_Silvia) June 9, 2020

Stan Lee: " I'd make people not hate each other because of their religion, because of their nationality, because of any stupid reason. If we can abolish hatred, we live on this gorgeous planet." pic.twitter.com/lxHzUWSkCL

I agree. And I hope the upheaval doesn’t mean “more Black artists hired at institutions,” but recognizing that the institutions themselves are unreformable bulwarks of white supremacy, and must end. Which one’ll be brave enough to recognize it first? https://t.co/aPpYSZXb4E— Monica Byrne (@monicabyrne13) June 9, 2020

Here’s why Trump has been catastrophic. Not the corruption or even the racism.— Virginia Heffernan (@page88) June 9, 2020

It’s this: He’s illegitimate.

He detonated a full-blown crisis of faith — distrust in the system that installed him.

From 2018:

https://t.co/RdpcXc6Rb9

https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/29288573/mark-cuban-white-people-uncomfortable-conversations-race

DALLAS -- Mavericks owner Mark Cuban implored people to have honest, uncomfortable conversations about race as a means of helping the country move forward.

Cuban made his comments Tuesday morning at an invitation-only event billed as "Courageous Conversation," a series of discussions about systemic racism and disparities facing the black community. The Mavs franchise organized and hosted the event in Victory Plaza outside the American Airlines Center, recruiting several prominent local officials to take part.

...Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins and Dallas Police Chief Renee Hall stressed the need for police reform while speaking during the second panel of the event.

"We need to radically transform the way we do policing in this country and this community," Jenkins said, adding that he'd recently met virtually with activists who had a list of 10 suggested steps.

Hall, a black woman who was appointed to her position in September 2017, opened her speech by noting that law enforcement was created in America to capture escaped slaves. She said that culture still permeates police departments.

"We have not gotten it right," Hall said, referring to police departments around the country. "There have been many unarmed black men killed at the hands of law enforcement, and we must own that. We must acknowledge it.

"There are 800,000 law enforcement officers, men and women, in this country and we all watched. We all watched one of our own put a knee on a black man's neck with no regard for human life, with no empathy, wearing the same uniform we wear, upholding the same laws that we uphold. And it made us all sick to our stomach. So we recognize there is work to do."

Hall has made improving the diversity of the Dallas Police Department a priority, wanting a unit that reflects the demographics of its community.

"We're committed to moving this city forward," Hall said. "We're committed to acknowledging those things that are broken, and we're focusing alongside our committee on facing them.

"So we just ask for the grace, we ask for the forgiveness, because we do wholeheartedly apologize for the wrongs that law enforcement has imposed on the African American community and on the Hispanic community over the years. We apologize. But please allow us the grace to fix it and move forward, because we're committed to that."

When atheists and atheist organizations attacked and deplatformed me for speaking out about misogyny in the movement I thought “well that’s why humanism is better. Humanism holds feminism as an essential ideal.” Anyway pic.twitter.com/AezUiugenx— Rebecca Watson (@rebeccawatson) June 9, 2020

When Black Lives Matter meets Gay Pride https://t.co/MKMi6g3xSP— LZ Granderson (@LZGranderson) June 12, 2020

— Ganzeer | جنزير (@ganzeer) June 12, 2020

White supremacy is more than the idea that Whites are superior to people of color; it is the deeper premise that supports this idea - the definition of Whites as the norm or the standard for human and people of color as a deviation from that norm— Melissa "Missy" Mariposa☂️ (@ingodwetryst) June 12, 2020

-Robin DiAngelo#BlackLivesMatter

In spirit it's a hack. https://t.co/rcw90UXZXk— Motherboard (@motherboard) June 12, 2020

Don’t look at this 🙈 #marvelcomics pic.twitter.com/fWpton3TqS— Adam Kubert (@AdamKubert) June 12, 2020

The White House put up a wall. The people ‘made it beautiful.’

The Self-Help Life CycleI've been thinking a lot about what it means to touch each other during a pandemic, and what might happen when we can't. I wrote and drew about it for the New York Times: https://t.co/sao6qKJrbx— Kristen Radtke (@KristenRadtke) March 19, 2020

by

|

Kristen Radtke is an illustrator and author of the graphic memoir “Imagine Wanting Only This.”

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, sign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar. And listen to us on the Book Review podcast.

https://twitter.com/i/events/1268960455617204224?s=13

Hello!! My names Nia and I like drawing pretty black girls ☺️#drawingwhileblack pic.twitter.com/qR4cD42DQ5— nia (@peachpodt) June 5, 2020

Hello #drawingwhileblack I'm Ibim Cookey a Nigerian Artist, Using Art as a tool to Promote Black cultural heritage and power. Kindly RT.. pic.twitter.com/7I7ugXhwmS— ibimcookey (@iamibimcookey) June 5, 2020

This is me. #drawingwhileblack https://t.co/yXk4bj4QXA— Ray-Anthony Height (@RAHeight) June 5, 2020

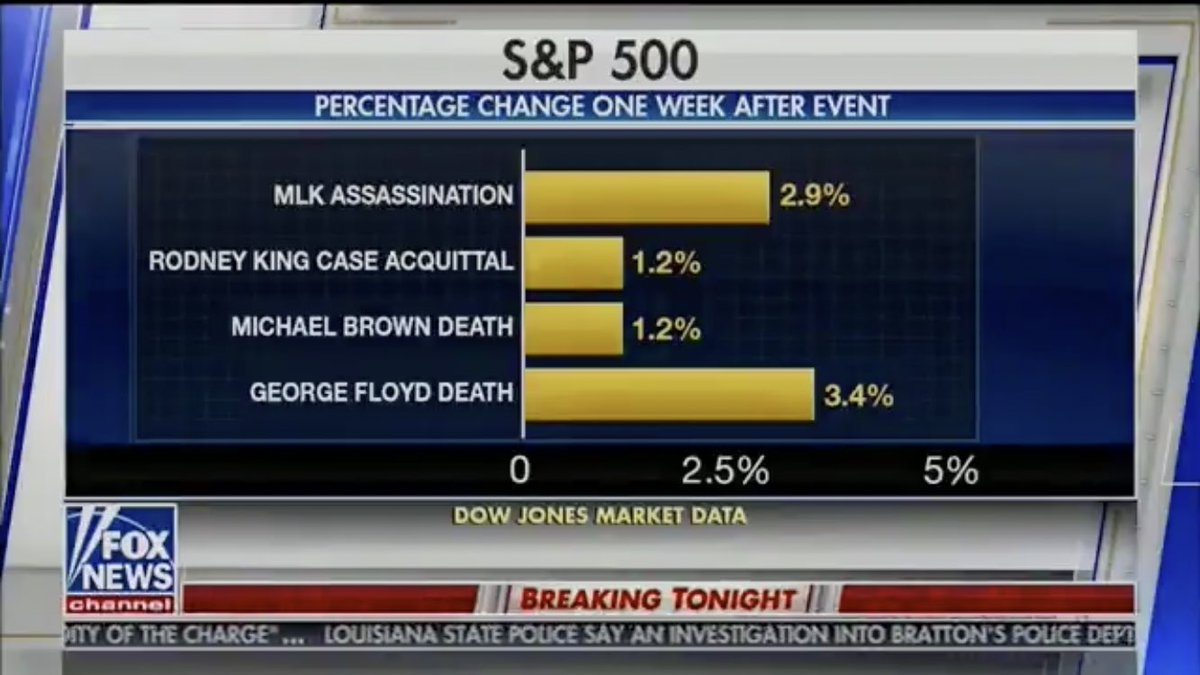

Fox News graphic: police killing and beating black people is good for the stock market

This was on Fox News, as reported by a number of reporters and viewers: a chart showing upticks in the S&P 500 stock index after killings of black people and the acquittal of the police offers filmed beating Rodney King. The defense is that it's a fact. Facts can't be racist, can they? There's no element of choice in how facts are identified, put in context and presented, is there? Maybe Fox News is actually critiquing capitalism!

I have revised the old joke from The Simpsons to bring it up to date:

'NO KNEELING!' — Donald Trump, who couldn't kneel if he tried

Yes, we regret to inform you that Large Adult President Donald Trump said something stupid again on the Twitters.

Tweeted the impeached Donald:

...We should be standing up straight and tall, ideally with a salute, or a hand on heart. There are other things you can protest, but not our Great American Flag - NO KNEELING!

NO KNEELING.

https://science.slashdot.org/story/20/06/06/2226206/how-iceland-virtually-eliminated-its-coronavirus-cases

How Iceland 'Virtually Eliminated' Its Coronavirus Cases (newyorker.com)

Iceland is the most sparsely-populated country in Europe, with a population of 364,134 spread across 40,000 square miles (103,000 square kilometers). But the New Yorker notes Iceland has "virtually eliminated" Covid-19 cases -- and tries to explore how they did it.

By February 28th, Iceland had already implemented a contact-tracing team. "And then, two hours later, we got the call," remembers a detective with the Reykjavík police department.A man who'd recently been skiing in the Dolomites had become the country's first known coronavirus patient... Anyone who'd spent more than fifteen minutes near the man in the days before he'd experienced his first symptoms was considered potentially infected. ("Near" was defined as within a radius of two metres, or just over six feet.) The team came up with a list of fifty-six names. By midnight, all fifty-six contacts had been located and ordered to quarantine themselves for fourteen days.

The first case was followed by three more cases, then by six, and then by an onslaught. By mid-March, confirmed COVID cases in Iceland were increasing at a rate of sixty, seventy, even a hundred a day. As a proportion of the country's population, this was far faster than the rate at which cases in the United States were growing. The number of people the tracing team was tracking down, meanwhile, was rising even more quickly. An infected person might have been near five other people, or fifty-six, or more. One young woman was so active before she tested positive — going to classes, rehearsing a play, attending choir practice — that her contacts numbered close to two hundred. All were sent into quarantine.

The tracing team, too, kept growing, until it had fifty-two members. They worked in shifts out of conference rooms in a Reykjavík hotel that had closed for lack of tourists. To find people who had been exposed, team members scanned airplane manifests and security-camera footage. They tried to pinpoint who was sitting next to whom on buses and in lecture halls. One man who fell ill had recently attended a concert. The only person he remembered having had contact with while there was his wife. But the tracing team did some sleuthing and found that after the concert there had been a reception. "In this gathering, people were hugging, and eating from the same trays," Pálmason told me. "So the decision was made — all of them go into quarantine." If you were returning to Iceland from overseas, you also got a call: put yourself in quarantine. At the same time, the country was aggressively testing for the virus — on a per-capita basis, at the highest rate in the world...

[B]y mid-May, when I went to talk to Pálmason, the tracing team had almost no one left to track. During the previous week, in all of Iceland, only two new coronavirus cases had been confirmed. The country hadn't just managed to flatten the curve; it had, it seemed, virtually eliminated it.

A biotech firm called deCODE Genetics (owned by the American multinational biopharmaceutical company Amgen) also offered its own facilities for screening tests, which "picked up many cases that otherwise would have been missed," according to the article. "These cases, too, were referred to the tracing team. By May 17th, Iceland had tested 15.5 per cent of its population for the virus."Meanwhile, deCODE was also sequencing the virus from every Icelander whose test had come back positive. As the virus is passed from person to person, it picks up random mutations. By analyzing these, geneticists can map the disease's spread...

[R]esearchers at deCODE found that, while attention had been focussed on Italy, the virus had been quietly slipping into the country from several other nations, including Britain. Travellers from the West Coast of the U.S. had brought in one strain, and travellers from the East Coast another. The East Coast strain had been imported to America from Italy or Austria, then exported back to Europe.

By February 28th, Iceland had already implemented a contact-tracing team. "And then, two hours later, we got the call," remembers a detective with the Reykjavík police department.A man who'd recently been skiing in the Dolomites had become the country's first known coronavirus patient... Anyone who'd spent more than fifteen minutes near the man in the days before he'd experienced his first symptoms was considered potentially infected. ("Near" was defined as within a radius of two metres, or just over six feet.) The team came up with a list of fifty-six names. By midnight, all fifty-six contacts had been located and ordered to quarantine themselves for fourteen days.

The first case was followed by three more cases, then by six, and then by an onslaught. By mid-March, confirmed COVID cases in Iceland were increasing at a rate of sixty, seventy, even a hundred a day. As a proportion of the country's population, this was far faster than the rate at which cases in the United States were growing. The number of people the tracing team was tracking down, meanwhile, was rising even more quickly. An infected person might have been near five other people, or fifty-six, or more. One young woman was so active before she tested positive — going to classes, rehearsing a play, attending choir practice — that her contacts numbered close to two hundred. All were sent into quarantine.

The tracing team, too, kept growing, until it had fifty-two members. They worked in shifts out of conference rooms in a Reykjavík hotel that had closed for lack of tourists. To find people who had been exposed, team members scanned airplane manifests and security-camera footage. They tried to pinpoint who was sitting next to whom on buses and in lecture halls. One man who fell ill had recently attended a concert. The only person he remembered having had contact with while there was his wife. But the tracing team did some sleuthing and found that after the concert there had been a reception. "In this gathering, people were hugging, and eating from the same trays," Pálmason told me. "So the decision was made — all of them go into quarantine." If you were returning to Iceland from overseas, you also got a call: put yourself in quarantine. At the same time, the country was aggressively testing for the virus — on a per-capita basis, at the highest rate in the world...

[B]y mid-May, when I went to talk to Pálmason, the tracing team had almost no one left to track. During the previous week, in all of Iceland, only two new coronavirus cases had been confirmed. The country hadn't just managed to flatten the curve; it had, it seemed, virtually eliminated it.

A biotech firm called deCODE Genetics (owned by the American multinational biopharmaceutical company Amgen) also offered its own facilities for screening tests, which "picked up many cases that otherwise would have been missed," according to the article. "These cases, too, were referred to the tracing team. By May 17th, Iceland had tested 15.5 per cent of its population for the virus."Meanwhile, deCODE was also sequencing the virus from every Icelander whose test had come back positive. As the virus is passed from person to person, it picks up random mutations. By analyzing these, geneticists can map the disease's spread...

[R]esearchers at deCODE found that, while attention had been focussed on Italy, the virus had been quietly slipping into the country from several other nations, including Britain. Travellers from the West Coast of the U.S. had brought in one strain, and travellers from the East Coast another. The East Coast strain had been imported to America from Italy or Austria, then exported back to Europe.

A mounting wave of protests calling for police reform swept across the United States on Sunday, while a majority of the Minneapolis City Council pledges to disband the city's police department in favor of a community-led model. Subscribe: http://smarturl.it/reuterssubscribe Reuters brings you the latest business, finance and breaking news video from around the globe. Our reputation for accuracy and impartiality is unparalleled. Get the latest news on: http://reuters.com/ Follow Reuters on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Reuters Follow Reuters on Twitter: https://twitter.com/Reuters Follow Reuters on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/reuters/?hl=en

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/06/07/defund-police-heres-what-that-really-means/

Defund the police? Here’s what that really means.

June 7, 2020 at 3:37 p.m. PDT

Be not afraid. “Defunding the police” is not as scary (or even as radical) as it sounds, and engaging on this topic is necessary if we are going to achieve the kind of public safety we need. During my 25 years dedicated to police reform, including in places such as Ferguson, Mo., New Orleans and Chicago, it has become clear to me that “reform” is not enough. Making sure that police follow the rule of law is not enough. Even changing the laws is not enough.

To fix policing, we must first recognize how much we have come to over-rely on law enforcement. We turn to the police in situations where years of experience and common sense tell us that their involvement is unnecessary, and can make things worse. We ask police to take accident reports, respond to people who have overdosed and arrest, rather than cite, people who might have intentionally or not passed a counterfeit $20 bill. We call police to roust homeless people from corners and doorsteps, resolve verbal squabbles between family members and strangers alike, and arrest children for behavior that once would have been handled as a school disciplinary issue.

Demonstrators paint the words “defund the police” as they protest near the White House on Saturday. (Jacquelyn Martin/AP)

Police themselves often complain about having to “do too much,” including handling social problems for which they are ill-equipped. Some have been vocal about the need to decriminalize social problems and take police out of the equation. It is clear that we must reimagine the role they play in public safety.

Defunding and abolition probably mean something different from what you are thinking. For most proponents, “defunding the police” does not mean zeroing out budgets for public safety, and police abolition does not mean that police will disappear overnight — or perhaps ever. Defunding the police means shrinking the scope of police responsibilities and shifting most of what government does to keep us safe to entities that are better equipped to meet that need. It means investing more in mental-health care and housing, and expanding the use of community mediation and violence interruption programs.

Police abolition means reducing, with the vision of eventually eliminating, our reliance on policing to secure our public safety. It means recognizing that criminalizing addiction and poverty, making 10 million arrests per year and mass incarceration have not provided the public safety we want and never will. The “abolition” language is important because it reminds us that policing has been the primary vehicle for using violence to perpetuate the unjustified white control over the bodies and lives of black people that has been with us since slavery. That aspect of policing must be literally abolished.

Still, even as we try to shift resources from policing to programs that will better promote fairness and public safety, we must continue the work of police reform. We cannot stop regulating police conduct now because we hope someday to reduce or eliminate our reliance on policing. We must ban chokeholds and curb the use of no-knock warrants; we must train officers how to better respond to people in mental health crises, and we must teach officers to be guardians, not warriors, to intervene to prevent misconduct and to understand and appreciate the communities they serve.

Why must we work on parallel tracks? First, all police will not be defunded or abolished anytime soon, and we cannot wait to make changes that will save lives and reduce policing harm now. Experienced advocates know this. This is why, for example, Campaign Zero just launched the #8cantwait campaign, which urges law enforcement agencies to immediately adopt eight use of force reforms, even as it continues its divest/invest strategy to end police killings.

More fundamentally, we must continue with reforms because abolition doesn’t go far enough. Policing didn’t invent America’s institutionalized racism, social inequity or stereotyped masculinity: Policing harms are a product of these broader pathologies. If we were to get rid of policing tomorrow, those pathologies would remain. And they would continue to be deadly: Race bias in our health-care system has likely killed far more African Americans and Latinx via covid-19 than the police have this year. Successful police reforms help us learn how to identify and mitigate the harms of these structural features, even as we work to remake them.

In this moment, we have a chance to make not just policing, but our entire country, fairer and safer. We must think creatively and educate ourselves. We must ask hard questions and demand answers about public safety budgets.

We should have unflinching debates about when, where and how to seek police reforms instead of defunding. But we should move forward on both tracks so that we can save lives even as we transform the police.

'Globally It's Worsening,' WHO Says of Coronavirus Pandemic (pbs.org)

An anonymous reader quotes a report from PBS NewsHour:The head of the World Health Organization warned that the coronavirus pandemic is worsening globally, even as the situation in Europe is improving. At a press briefing on Monday, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus noted that about 75% of cases reported to the U.N. health agency on Sunday came from 10 countries in the Americas and South Asia. He noted that more than 100,000 cases have been reported on nine of the past 10 days -- and that the 136,000 cases reported Sunday was the biggest number so far. Tedros said most countries in Africa are still seeing an increase in cases, including in new geographic areas even though most countries on the continent have fewer than 1,000 cases. "At the same time, we're encouraged that several countries around the world are seeing positive signs," Tedros said. "In these countries, the biggest threat now is complacency."There was some good news to come from the media briefing. "From the data we have, it still seems to be rare that an asymptomatic person actually transmits onward to a secondary individual," said Maria Van Kerkhove on Monday. "We have a number of reports from countries who are doing very detailed contact tracing. They're following asymptomatic cases, they're following contacts and they're not finding secondary transmission onward. It is very rare -- and much of that is not published in the literature," she said. "We are constantly looking at this data and we're trying to get more information from countries to truly answer this question. It still appears to be rare that an asymptomatic individual actually transmits onward."

Tedros also dedicated time to addressing protests across the globe fighting against police brutality and systemic racism. "WHO fully supports equality and the global movement against racism," Tedros said during the briefing. "We reject discrimination of all kinds. We encourage all those protesting around the world to do so safely."

Tedros also dedicated time to addressing protests across the globe fighting against police brutality and systemic racism. "WHO fully supports equality and the global movement against racism," Tedros said during the briefing. "We reject discrimination of all kinds. We encourage all those protesting around the world to do so safely."

Titan Is Migrating Away From Saturn 100 Times Faster Than Previously Predicted (phys.org)

According to a study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, the orbit of Saturn's moon Titan is expanding at a rate about 100 times faster than expected. "The research suggests that Titan was born much closer to Saturn and migrated out to its current distance of 1.2 million kilometers (about 746,000 miles) over 4.5 billion years," reports Phys.Org. From the report:In the work detailed in the Nature Astronomy paper, two teams of researchers each used a different technique to measure Titan's orbit over a period of 10 years. One technique, called astrometry, produced precise measurements of Titan's position relative to background stars in images taken by the Cassini spacecraft. The other technique, radiometry, measured Cassini's velocity as it was affected by the gravitational influence of Titan. "By using two completely independent data sets -- astrometric and radiometric -- and two different methods of analysis, we obtained results that are in full agreement," says the study's first author, Valery Lainey formerly of JPL (which Caltech manages for NASA), now of Paris Observatory, PSL University. Lainey worked with the astrometry team.

The results are also in agreement with a theory proposed in 2016 by Fuller, who predicted that Titan's migration rate would be much faster than standard tidal theories estimated. His theory notes that Titan is expected to gravitationally squeeze Saturn with a particular frequency that makes the planet oscillate strongly, similarly to how swinging your legs on a swing with the right timing can drive you higher and higher. This process of tidal forcing is called resonance locking. Fuller proposed that the high amplitude of Saturn's oscillation would dissipate a lot of energy, which in turn would cause Titan to migrate outward away from the planet at a faster rate than previously thought. Indeed, the observations both found that Titan is migrating away from Saturn at a rate of 11 centimeters per year, more than 100 times faster than previous theories predicted.

The results are also in agreement with a theory proposed in 2016 by Fuller, who predicted that Titan's migration rate would be much faster than standard tidal theories estimated. His theory notes that Titan is expected to gravitationally squeeze Saturn with a particular frequency that makes the planet oscillate strongly, similarly to how swinging your legs on a swing with the right timing can drive you higher and higher. This process of tidal forcing is called resonance locking. Fuller proposed that the high amplitude of Saturn's oscillation would dissipate a lot of energy, which in turn would cause Titan to migrate outward away from the planet at a faster rate than previously thought. Indeed, the observations both found that Titan is migrating away from Saturn at a rate of 11 centimeters per year, more than 100 times faster than previous theories predicted.

Astronomers have found a planet like Earth orbiting a star like the Sun (technologyreview.com)

Iwastheone writes:Three thousand light-years from Earth sits Kepler 160, a sun-like star that’s already thought to have three planets in its system. Now researchers think they’ve found a fourth. Planet KOI-456.04, as it’s called, appears similar to Earth in size and orbit, raising new hopes we’ve found perhaps the best candidate yet for a habitable exoplanet that resembles our home world. The new findings bolster the case for devoting more time to looking for planets orbiting stars like Kepler-160 and our sun, where there’s a better chance a planet can receive the kind of illumination that’s amenable to life.

Most exoplanet discoveries so far have been made around red dwarf stars. This isn’t totally unexpected; red dwarfs are the most common type of star out there. And our main method for finding exoplanets involves looking for stellar transits—periodic dips in a star’s brightness as an orbiting object passes in front of it. This is much easier to do for dimmer stars like red dwarfs, which are smaller than our sun and emit more of their energy as infrared radiation. The highest-profile discovery of this type is near our closest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri—a red dwarf with a potentially habitable planet called Proxima b (whose existence was, incidentally, confirmed in a new study published this week).

Data on the new exoplanet orbiting Kepler 160, published in Astronomy and Astrophysics on Thursday, points to a different situation entirely. From what researchers can tell, KOI 456.04 looks to be less than twice the size of Earth and is apparently orbiting Kepler-160 at about the same distance from Earth to the sun (one complete orbit is 378 days). Perhaps most important, it receives about 93% as much light as Earth gets from the sun.

This is critical, because one of the biggest obstacles to habitability around red dwarf stars is they can emit a lot of high-energy flares and radiation that could fry a planet and any life on it. By contrast, stars like the sun—and Kepler-160, in theory—are more stable and suitable for the evolution of life.

The authors found KOI-456.04 by reanalyzing old data collected by NASA’s Kepler mission. The team employed two new algorithms to analyze the stellar brightness observed from Kepler-160. The algorithms were designed to look at dimming patterns on a more granular and gradual level, rather than seeking the abrupt dips and jumps that had previously been used to identify exoplanets in the star system.

Right now the researchers say it’s 85% probable KOI-456.04 is an actual planet. But it could still be an artifact of Kepler’s instruments or the new analysis—an object needs to pass a threshold of 99% to be a certified exoplanet. Getting that level of certainty will require direct observations. The instruments on NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope are expected to be up to the task, as are those on ESA’s PLATO space telescope, due to launch in 2026

Most exoplanet discoveries so far have been made around red dwarf stars. This isn’t totally unexpected; red dwarfs are the most common type of star out there. And our main method for finding exoplanets involves looking for stellar transits—periodic dips in a star’s brightness as an orbiting object passes in front of it. This is much easier to do for dimmer stars like red dwarfs, which are smaller than our sun and emit more of their energy as infrared radiation. The highest-profile discovery of this type is near our closest neighboring star, Proxima Centauri—a red dwarf with a potentially habitable planet called Proxima b (whose existence was, incidentally, confirmed in a new study published this week).

Data on the new exoplanet orbiting Kepler 160, published in Astronomy and Astrophysics on Thursday, points to a different situation entirely. From what researchers can tell, KOI 456.04 looks to be less than twice the size of Earth and is apparently orbiting Kepler-160 at about the same distance from Earth to the sun (one complete orbit is 378 days). Perhaps most important, it receives about 93% as much light as Earth gets from the sun.

This is critical, because one of the biggest obstacles to habitability around red dwarf stars is they can emit a lot of high-energy flares and radiation that could fry a planet and any life on it. By contrast, stars like the sun—and Kepler-160, in theory—are more stable and suitable for the evolution of life.

The authors found KOI-456.04 by reanalyzing old data collected by NASA’s Kepler mission. The team employed two new algorithms to analyze the stellar brightness observed from Kepler-160. The algorithms were designed to look at dimming patterns on a more granular and gradual level, rather than seeking the abrupt dips and jumps that had previously been used to identify exoplanets in the star system.

Right now the researchers say it’s 85% probable KOI-456.04 is an actual planet. But it could still be an artifact of Kepler’s instruments or the new analysis—an object needs to pass a threshold of 99% to be a certified exoplanet. Getting that level of certainty will require direct observations. The instruments on NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope are expected to be up to the task, as are those on ESA’s PLATO space telescope, due to launch in 2026

Twitter Deletes Over 170,000 Accounts Tied To Chinese Propaganda Efforts (thehill.com)

Twitter announced Thursday that it had deleted more than 170,000 accounts tied to a Chinese state-linked operation that were spreading deceptive information around the COVID-19 virus, political dynamics in Hong Kong, and other issues. The Hill reports:Almost 25,000 of the accounts that were deleted formed what Twitter described as the "core network," while around 150,000 accounts were amplifying messages from the core groups. "In general, this entire network was involved in a range of manipulative and coordinated activities," the company wrote in a blog post. "They were Tweeting predominantly in Chinese languages and spreading geopolitical narratives favorable to the Communist Party of China (CCP), while continuing to push deceptive narratives about the political dynamics in Hong Kong."

According to an analysis of the accounts by the Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO), many of the accounts shut down were tweeting about the COVID-19 pandemic, with activity around this issue beginning in late January and reaching its peak in late March. The accounts primarily praised China's response to the COVID-19 crisis. While most of the accounts had less than 10 followers and no bios, the SIO found that they had tweeted almost 350,000 times before being shut down.

According to an analysis of the accounts by the Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO), many of the accounts shut down were tweeting about the COVID-19 pandemic, with activity around this issue beginning in late January and reaching its peak in late March. The accounts primarily praised China's response to the COVID-19 crisis. While most of the accounts had less than 10 followers and no bios, the SIO found that they had tweeted almost 350,000 times before being shut down.

Scientists Have Discovered Vast Unidentified Structures Deep Inside the Earth (vice.com)

Scientists combed through nearly 30 years of earthquake data to probe huge and mysterious objects near the Earth's core. From a report:Scientists have discovered a vast structure made of dense material occupying the boundary between Earth's liquid outer core and the lower mantle, a zone some 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) beneath our feet. The researchers used a machine learning algorithm that was originally developed to analyze distant galaxies to probe the mysterious phenomenon occurring deep within our own planet, according to a paper published on Thursday in Science. One of these enormous anomalies, located deep under the Marquesas Islands, had never been detected before, while another structure beneath Hawaii was found to be much larger than previously estimated.

Scientists led by Doyeon Kim, a seismologist and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, fed seismograms captured from hundreds of earthquakes that occurred between 1990 to 2018 into an algorithm called Sequencer. While seismological studies tend to focus on relatively small datasets of regional earthquake activity, Sequencer allowed Kim and his colleagues to analyze 7,000 measurements of earthquakes -- each with a magnitude of at least 6.5 -- that shook the subterranean world under the Pacific Ocean within the past three decades. "This study is very special because, for the first time, we get to systematically look at such a large dataset that actually covers more or less the entire Pacific basin," Kim said in a call. Though scientists have previously mapped out structures deep inside Earth, this study presents a rare opportunity to "bring everything in together and try to explain it in a global context," he noted.

Scientists led by Doyeon Kim, a seismologist and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Maryland, fed seismograms captured from hundreds of earthquakes that occurred between 1990 to 2018 into an algorithm called Sequencer. While seismological studies tend to focus on relatively small datasets of regional earthquake activity, Sequencer allowed Kim and his colleagues to analyze 7,000 measurements of earthquakes -- each with a magnitude of at least 6.5 -- that shook the subterranean world under the Pacific Ocean within the past three decades. "This study is very special because, for the first time, we get to systematically look at such a large dataset that actually covers more or less the entire Pacific basin," Kim said in a call. Though scientists have previously mapped out structures deep inside Earth, this study presents a rare opportunity to "bring everything in together and try to explain it in a global context," he noted.

I’ve been getting a lot of questions from my non-Black friends about how to be a better ally to Black people. I suggest unlearning and relearning through literature as just one good jumping off point, and have broken up my anti-racist reading list into sections: pic.twitter.com/gj5uko69OY— Victoria Alexander (@victoriaalxndr) May 30, 2020

Meanwhile, literal Neo-Nazis are radicalizing young white men to join terrorist cells in the exact same way al-Qaeda and ISIS have.— Jared Yates Sexton (@JYSexton) June 14, 2020

What we've done is focus on a problem abroad and completely ignored a growing problem within.

Because of white supremacy.

34/ pic.twitter.com/mil48nrG3B

In addition, on Friday, June 19th, we’re donating 100% of our share of sales to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a racial justice organization with a long history of effectively enacting change through litigation, advocacy, and public education. Please read our statement here.

The recent killings of George Floyd, Tony McDade, Sean Reed, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and the ongoing state-sanctioned violence against black people in the US and around the world are horrific tragedies. We stand with those rightfully demanding justice, equality, and change, and people of color everywhere who live with racism every single day, including many of our fellow employees and artists and fans in the Bandcamp community.

So this coming Juneteenth (June 19, from midnight to midnight PDT) and every Juneteenth hereafter, for any purchase you make on Bandcamp, we will be donating 100% of our share of sales to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a national organization that has a long history of effectively enacting racial justice and change through litigation, advocacy, and public education. We’re also allocating an additional $30,000 per year to partner with organizations that fight for racial justice and create opportunities for people of color.

The current moment is part of a long-standing, widespread, and entrenched system of structural oppression of people of color, and real progress requires a sustained and sincere commitment to political, social, and economic racial justice and change. We’ll continue to promote diversity and opportunity through our mission to support artists, the products we build to empower them, who we promote through the Bandcamp Daily, our relationships with local artists and organizations through our Oakland space, how we operate as a team, and who and how we hire.

Beyond that, we encourage everyone in the Bandcamp community to look for ways to support racial equality in your own local community, and as a company we’ll continue to look for more opportunities to support racial justice, equality and change.

I saw my old colleague Chris Cooper in the news -- some crazy racist woman tried to have him killed by cops in Central Part. I knew Chris when we were both at Marvel. He was a lovely guy, and I enjoyed his company immensely. We definitely got slightly drunk together at a Marvel summit out in Glen Cove. I always liked him a lot. He did one of the funniest things I ever saw at my time at Marvel. Back then, Marvel would release a summer book called the Marvel Swimsuit Issue, which was exactly as awful as you think it is. What they used to call "fan service" and "good girl art."

Except one year Chris Cooper somehow got hold of it. And that year's issue was the gayest thing you ever saw. Like, gaydar installations all over the Northern Hemisphere just straight up burst into flames. Anyone who beheld that book from a distance of twenty feet became, by genetic testing, 3% gayer. It was so fucking funny, it was so not what Marvel did at the time, and it was so well played.

Chris, wherever you are, I hope life is becoming more peaceful.

https://bleedingcool.com/comics/warren-ellis-marvel-illustrated-swimsuit-went-gay/

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 2006.13 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1807 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment