A Sense of Doubt blog post #2985 - The Importance of Literary Magazines

The main critiques of literary journals are: that they are too niche, that their readership is too small to remain culturally relevant, and that the state-sponsored funding that props them up is a waste of taxpayer money. If you agree with the above critiques, you are probably missing the point of literary journals. And that point is community.

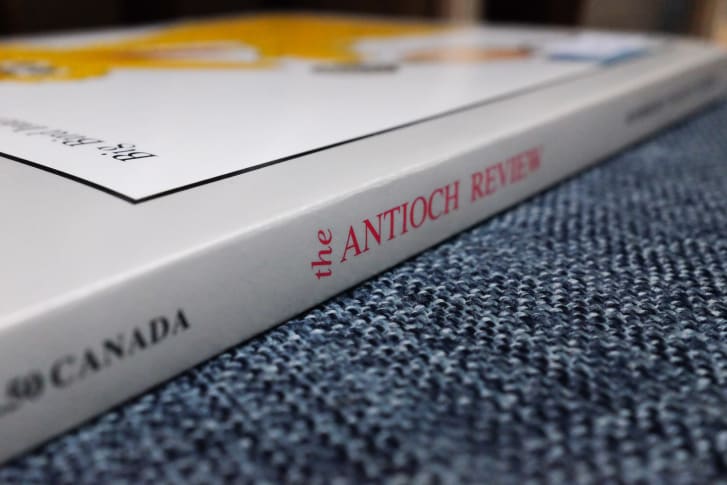

It’s true, sales of Canadian literary journals are so low that their operation relies primarily on financial donations, operating grants, and volunteers. But measuring the value of literary journals by sales alone is like measuring the value of a library simply by how many books are withdrawn. Literary journals, like libraries, offer a whole lot more than casual reading.

For starters, emerging artists rely on them. Literary journals are a writer’s first proving ground. Having work published in a journal means that it has been vetted by professional editors and has risen above the other submissions—a major accomplishment, considering the healthy volume of submissions that literary journals receive. This vetting process is also relevant to many grant applications catering to emerging writers. Typically, grants require applicants to have a minimum number of pieces published by literary journals before applying, meaning that publication in literary journals adds literal value to a writer’s future. And behind all of these facts lies credibility and confidence, qualities vital to the growth of emerging writers. Qualities that literary journals provide.

Granting bodies such as the Ontario Arts Council (OAC) also rely on literary journals for grant distribution. Literary journals, like most magazines, inherently foster editors. With the sheer quantity of submissions that they must sort and vet, these editors have a keen knowledge of writing quality and writing trends. The OAC utilizes this expertise by partnering with literary journals in order to help distribute their Recommender Grants for Writers.

The vetting process is also professionally important for the administrative and professional sides of the literary community. Book publishers, literary agents, festival organizers, anthologizers, and other literary professionals are reading literary journals, scanning for quality, remembering names, and surveilling trends. I’m not saying that publishing in literary journals will get you an agent, a book deal, and a national reading tour. But if you’re hoping for your manuscript to emerge from the slush pile, the exposure of your name and work in a literary journal can increase your chances.

As for the readership of literary journals, yes, it is small. But it is not irrelevant. The readership is largely made up of other writers and academics. These are people connected to artistic and intellectual communities around the world, and literary journals are a means of idea communication within and between these communities.

While the financial arguments for literary journals are admittedly poor, most journals still do pay honorariums to their contributors, and employ one or two managing editors as well. These are people undertaking their dream jobs of working with words every day, even if it is for poverty-line wages.

There is also an argument for the creation of indirect jobs and job training. The creation of a magazine requires submission readers, proofreaders, layout designers, website designers, content editors, and administrative support. Some larger, more financially solvent literary journals pay a team of freelancers to fill these roles. Most small literary journals complete these tasks with a team of volunteers, people passionate about literature and willing to learn these important skills. For this latter group, literary journals exist as a place to learn, and a place to test the publishing industry before dedicating themselves to education programs or careers. They are also a place for learners to make connections with established authors and editors, and acquire references that are essential for job, post-secondary, mentorship, residency, and grant applications.

Lastly, it’s important to note that literary journals don’t just publish an issue and then call it a day. Literary journals are also physically involved in the community. Most host launch parties where authors gather to read and support one another. Some of the larger literary journals sponsor live events like interviews, panels, and festival events with their editors and/or contributors. Many run literary contests. Several of them host regular writing workshops in the local community. Effectively, literary journals create the moments when literary correspondence, friendships, and even future mentorships begin. These are moments that define community.

So yes, literary journals are very important.

Long-standing literary magazines are struggling to stay afloat. Where do they go from here?

Written byLeah Asmelash, CNN

https://www.thepublishingpost.com/post/the-importance-of-literary-magazines

The Importance of Literary Magazines

I’m a lit mag newbie. I stumbled across the world of literary

magazines and journals on Twitter and, as both a reader and hopeful writer, I

was intrigued. The indie lit mag community is a hub of creativity, combining

multiple art forms: poetry, prose, non-fiction, personal essays, book reviews,

graphic design and photography, among others. Such magazines are rarely

discussed in the world of publishing, yet they provide underrepresented voices

with opportunities to find their footing in the literary world.

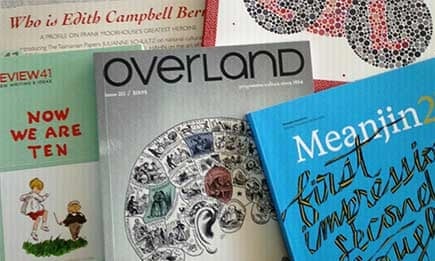

Literary magazines themselves are not new. From the Nouvelles de la republique des lettres in 1684 to the Edinburgh Review in 1802, they’ve been around for centuries. After an increase in the number of journals in the mid 20th century, the late 20th century saw the emergence of online lit mags, thereby revolutionising small presses. Lit mags rely heavily on social media in order to gain submissions, which are often based on a particular theme.

While some lit mags do print runs of each issue, others have a solely online presence, sharing their work for free via a blog or website. Founder and editor of lit mag Opia and member of the editorial team at The Publishing Post, Olga Bialasik believes that magazines and journals “are a really great way of gaining publishing credits, especially for writers whose goal isn’t necessarily to write a full length novel, which is a common assumption.” Being published in a small press brings with it the chance to win the Pushcart prize, honouring the best "poetry, short fiction, essays or literary whatnot” from the previous year, as well as the O Henry Award for short stories. These awards can provide early recognition for writers without the need for book deals or the expense of self-publication in print.

And technology isn’t the only reason that lit mags are a step ahead in terms of accessibility. Independent publications are so often disregarded by the publishing industry in favour of traditional print publishing, where underrepresented writers are consistently overlooked. 2020 saw an examination of the lack of diversity in the publishing industry, with LL McKinney’s #PublishingPaidMe hashtag highlighting the pay disparity between white authors and authors of colour. It saw publishers paying 6-figure advances to white authors, while award-winning Black authors had to fight for such salaries. Olga Bialasik also says that magazines “offer an opportunity to get published that… is a lot more attainable and accessible, particularly for underrepresented writers.” Opia is one of the many magazines dedicated to “elevating marginalised and underrepresented voices, including (but not limited to) BIPOC, LGBTQ+, women, immigrant, disabled, neurodiverse, and working-class writers, artists and creators.” Editors, most of whom work voluntarily while juggling jobs and degrees, are able to cultivate spaces that allow BIPOC, LGBTQ+ and disabled people to tell their stories and share their art in an industry that is 76% white, 74% cis, 81% straight and 89% non-disabled. (Lee and Low Diversity Baseline Survey, 2019).

Journals and small presses can also provide publishing hopefuls with invaluable experience in editing, social media marketing and web design. Many lit mags search for staff via Twitter, and these positions can almost always be carried out remotely, meaning that those living outside of London can still develop skills within a publishing environment. These positions, like so many in the industry, are usually voluntary as lit mags are almost exclusively volunteer run. However, having your name as part of a masthead can be a great addition to your CV and give great insight into the world of digital publishing.

It is clear that literary magazines are a modern medium in publishing, taking steps to carve out spaces that amplify the voices that go unheard in traditional publishing. They bring together art and aesthetic, and create a sense of community for writers of all backgrounds, while also allowing publishing hopefuls a chance to learn more about e-publishing. “The community is wonderful, friendly and extremely supportive… collaborating to make the space more, open, honest and safe for everyone.”

Check out more amazing literary magazines below:

https://www.pw.org/content/game_changers_literary_magazines_as_the_gateway_to_your_career

Game Changers: Literary Magazines as the Gateway to Your Career

A few years ago while I was teaching at a writers conference I met a young woman who wrote poetry but was otherwise unfamiliar with the world of writing and publishing. She tracked me down one afternoon to ask the question shared by so many aspiring writers: “How do I get published?”

It was a broad question, but I was game. I launched into an overview of the literary magazine landscape and submission process, including where to research journals, how to prepare a submission, the inevitability of rejection, and so on. The poet nodded along politely until I paused, at which point she clarified that she wasn’t interested in literary magazines.

“I want to publish a book,” she said. “How do I do that?”

For a moment I was at a loss. I wasn’t sure how to address her question while ignoring the existence of literary magazines and their place in the development of writing careers. That’s not to say that literary magazines absolutely must serve as a proving ground for writers (although in many cases, they do) or that prior publication is a prerequisite for a book contract. But the reality is that submitting to and publishing in literary journals serves as an excellent education for creative writers while offering a sturdy platform upon which to build a promising career. Let’s take a closer look at exactly why and how literary magazines can be so important.

Know Your Rights

First things first: Publishing individual poems, stories, or essays in literary magazines won’t hinder your ability to later include those same pieces in your own book. In fact, establishing a track record of such publication can only help, not hurt, your writing career.

“There are large benefits to publishing in literary magazines,” says Dani Hedlund, editor in chief and art director of F(r)iction, a literary magazine published by the Brink Literacy Project in Denver. “The first is craft—learning how to write incredibly good short form makes you a better long-form author. But it’s also a great way to integrate into the writing world, make connections, learn how to be professional, and build a better platform.”

If you scan the acknowledgements page in a collection of poetry, short stories, or essays, you’ll likely find that at least some of the individual pieces were first published in journals. (The Literary MagNet column in every issue of this magazine focuses on the literary magazines that first published an author’s work that now appears in a book.) While most literary publications accept only unpublished work (meaning the story, poem, or essay has never before been published anywhere, including on personal blogs or social media), after publication the rights to that work should revert back to the author, meaning the author once again has the right to publish it in a book, anthology, or a journal that accepts reprints.

Most contracts for print journals in the United States will require First North American Serial Rights, which grants a journal the right to be the first to publish your work in North America. Online journals may request “first rights” or “worldwide rights,” since work published online can be accessed anywhere. In either case the contract should specify that rights revert to the author after some specified period of time. Some magazines may require a period of exclusivity for a few months after publication to ensure the work doesn’t appear in competing markets at the same time, but that’s common practice so long as the timeframe is clearly defined. Red flags—which are rare, but I have seen a few crop up in my own career—include any contract that asks for “all rights” (this includes everything from reprint to film and audio rights, effectively cutting the author out of the creative decisions and financial compensation for all future deals involving the work), for rights “in perpetuity” (meaning the magazine or publisher will permanently control the rights to your work), or that designates your writing as “work for hire” (which indicates that the publisher will outright own the copyright to your writing).

As Hedlund points out, writers should always retain as many rights to their writing as possible, though in the case of an acceptance from a market splashy enough to alter the course of your career, you might make allowances. Some high-profile publications may require all rights to a piece, and each writer must consider whether the prestige and scope of that publication is worth it. In any case, read your contract carefully, and know that it’s perfectly acceptable to ask questions. If you still have concerns, you can join the Authors Guild, a professional organization that defends authors’ rights, to receive a contract review and legal assistance. (An annual membership starts at $135, or $35 for students.)

“Don’t be afraid of a contract,” Hedlund says. “Take a deep breath, have a cup of coffee, and go through it.”

Building Community

Publishing in a literary magazine is about more than your individual byline—it’s about entering into conversation with editors, other contributors, and potential readers.

“If your larger goal is to have a book published one day, and you’re submitting poems and getting a handful of them published, you can build a readership and promote excitement about the book itself,” says Jason Harris, a poet and editor in chief of Gordon Square Review, an online biannual published by the nonprofit Literary Cleveland.

“Building those networks is vital for selling a book, but it’s also just vital for being a creative,” adds Hedlund. “We’re all introverted weirdos, and we need to be around other introverted weirdos so we don’t become accountants.”

Even if you do work as an accountant by day, building the confidence to persist in the writing world, which is famously rife with rejection, is no small matter.

“I didn’t start submitting until years after the MFA because it was a scary thing. It felt so vulnerable, and it was an emotional hurdle at first,” says Yalitza Ferreras, who is the 2022–2023 Carol Houck Smith Fiction Fellow at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. But when Ferreras got her first story acceptance, from the Colorado Review, the experience was transformative. “I reached at least one person—the editor—with my work, and it felt really great. It felt like, Okay, I am a professional writer now.”

As validating as it is to receive an acceptance from a journal, some writers enjoy the freedom and immediacy of posting their work on a blog, personal website, or social media. How does that fit in with the literary magazine landscape?

“It depends on your goals,” Ferreras says. For writers who seek agents, acclaim, and a larger readership and community, literary magazines are the better path. “But if you’re prolific and have stories to spare and want to put some on your website, then great,” she says.

“Consider the lifespan of what you’re about to publish,” says Harris. “If you’re writing because you have something urgent to say and you don’t care if it gets published by anyone else, that’s what I would reserve the blog platform for—whereas if you’re drafting and redrafting a poem multiple times, and if you believe in it and envision it published at certain places, then think twice before putting it on a personal blog.”

Be advised that posting a piece of creative writing on your blog or social media is considered “previously published,” even if you later take it down. So when in doubt, don’t post.

From Anthologies to Agents

Yalitza Ferreras’s publication in the Colorado Review led to an unexpected windfall when her story, “The Letician Age,” was anthologized in The Best American Short Stories 2016—a career-changing honor available only to writing that first appeared in literary publications.

According to Hedlund, many journal editors will fight for their authors by nominating their work for awards and anthologies. F(r)iction even sends copies of the journal to literary agents and highlights which contributing writers are not yet represented.

For prose writers especially, publishing in literary journals can indeed attract attention from literary agents. Earlier in my career, multiple agents who read my work in journals sought me out. While there’s no guarantee that publishing in journals will be a direct pipeline to your dream agent, it’s a start, and even preliminary conversations with agents about your work can be illuminating. At the least, publishing in magazines helps build your résumé and puts you in a stronger position when you’re ready to query.

“With a really well-run journal, the author is also learning how to be a professional,” Hedlund says. “It’s often the very first time they get edits. So you’re learning your craft, interfacing with an editor, and learning how rights work. That will help you prepare, in a lower-stakes environment, for something with bigger stakes—like a book deal.”

Finally, while it’s not a glamorous benefit, submitting to literary magazines teaches writers how to weather rejection, an essential survival skill in this industry.

“Earlier in my career, I would get really down if I got rejected. I would start to spiral and think, Maybe I’m just not as good as other writers,” Harris says. “I’ve learned that a poem may get rejected thirty times, but that doesn’t change how I value the poem. Rejection has also taught me the importance of revision and being able to see the poem in a different way—but also to see myself in a different way because it builds a tougher skin.”

Practical Tips

Thousands of literary magazines are published today, from glossy print periodicals to niche online journals, with more being launched every year. With such a wide variety of markets available to writers, the submission process can seem daunting. Poets & Writers, NewPages, Duotrope, the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses, and Submittable offer lists of markets, and Harris also recommends chillsubs.com, which offers a search tool, a submission tracker, and an online community for writers. On Twitter, writers can access submission tips, deadline notifications, and other resources directly from editors and fellow writers.

“Social media is a great way to find information [about publishing],” Ferreras says. “The only reason I’m on social media is to learn about some of these things.”

After researching journals, the next step—and definitely don’t skip this one—is to actually read work in these journals to learn what will be a good fit for your own writing. You don’t have to read every issue of every magazine—that would be impossible—but read enough of a selection that you get a taste of the publication’s aesthetic and see how your own work measures up.

“The No. 1 mistake I see from writers is they don’t read the journals they’re submitting to, so they don’t understand whether they’re a good fit,” Hedlund says. F(r)iction gravitates toward “extraordinarily weird” work, she says, which makes it all too clear that the writers submitting grounded-in-reality stories or quiet vignettes have never read the magazine.

Submitting work that isn’t a match might not be a crime, but it wastes your time and the editors’ time. Not only are you more likely to receive an acceptance from a publication you already read and love, it’s also much more meaningful.

“Only submit to places where you actually want to be published,” Ferreras advises. “If you’re not excited about being in there, don’t do it.”

Next, be sure to follow each journal’s specific guidelines. As Harris points out, if a publication requests no more than three poems per submission, don’t send five. To an overworked editor, those extra poems are a burden—and the competition is so steep that it’s best not to give an editor an easy excuse to reject your work. Research appropriate manuscript formatting, submit only in the requested method and during the journal’s open submission period, and be prepared for a potentially lengthy wait. (Submitting to journals also teaches writers the art of patience.)

And when it comes to the cover letter, don’t overthink it. It is simply a place to say who you are, why you are submitting to this journal, and briefly list any relevant publications and honors. Hedlund reminds writers to make sure they spell the editor’s name correctly and be careful not to misgender an editor. Don’t try to be too clever or too familiar in a cover letter. When I worked as an editor, writers sometimes tried to exaggerate a connection we might share, or worse, they’d attempt to cut the queue by tracking down my personal e-mail address and pitching me that way. These tactics might feel a bit desperate at best, intrusive or irritating at worst. Don’t fabricate details in the cover letter, either, whether it’s about your credentials, if you’ve ever actually read the journal, or anything else. Lastly, never explain or summarize your poem, story, or essay in the cover letter. Let the work stand on its own. Most of all, make sure your work is as polished as possible before you hit Submit. Give yourself the best chance of connecting with an editor who just might open the door.

When that happens, celebrate your accomplishment—but then keep submitting new work. Literary publishing is incredibly rewarding artistically and personally, but it won’t bring immediate riches or fame.

Discovering Beauty

While publishing in literary magazines might not be remunerative, the experience can offer broader, more intangible benefits for writers.

“Publishing has taught me about myself and the things I want to write about,” Harris says. “I never would have made some of those connections if other people in the writing community hadn’t said, ‘Hey, I notice you write a lot about trees. Have you read this book? Have you read this writer?’ I started to figure out who I am as a writer and a poet.”

Harris’s words make me think of that poet at the writing conference. I hope she found her own way to engage with poetry and a writing community—whether that’s publishing a collection with a small press, entering chapbook contests, or submitting to literary journals. If she still doesn’t have any publications to list in her cover letter, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, it can be a gift, because editors love publishing new voices.

“It’s pretty much the best high we have as editors,” Hedlund says. “People love to discover something new and beautiful.”

The world of literary magazine publication is all about the new and the beautiful. Literary journals introduce us to up-and-coming authors, allow writers to develop their craft, and, if we’re lucky, swing open the gates to bigger, brighter literary careers.

Laura Maylene Walter is the author of the novel Body of Stars (Dutton, 2021), an Ohioana Book Awards finalist and a U.K. Booksellers Association Fiction Book of the Month selection. She is the Ohio Center for the Book Fellow at Cleveland Public Library, where she hosts Page Count, a literary podcast.

The Persistence of Litmags

July 7, 2015

Why on Earth would you start a literary magazine? You won’t get rich, or even very famous. You’ll have to keep your day job, unless you’re a student or so rich you don’t need a day job. You and your lucky friends and the people you hire—if you can afford to pay them—will use their time and energy on page layouts, bookkeeping, distribution, Web site coding and digital upkeep, and public readings and parties and Kickstarters and ways to wheedle big donors or grant applications so that you can put out issue two, and then three. You’ll lose time you could devote to your own essays or fiction or poems. Once your journal exists, it will wing its way into a world already full of journals, like a paper airplane into a recycling bin, or onto a Web already crowded with literary sites. Why would you do such a thing?

And yet people do, as they have for decades—no, centuries, though cheaper printing in the eighteen-nineties, Ditto machines in the nineteen-sixties and seventies, offset printing and, in the past two decades, Web-based publishing have made it at least seem easier for each new generation. In 1980, the Pushcart Press—known for its annual Pushcart Prizes—published a seven-hundred-and-fifty-page brick of a book, “The Little Magazine in America,” of memoirs and interviews with editors of small journals. “The Little Magazine in Contemporary America,” a much more manageable collection of interviews and essays that was published in April, looks at the years since then, the years that included—so say the book’s editors, Ian Morris and Joanne Diaz— “the end of the ascendancy of print periodicals,” meaning that the best small litmags have moved online.

They have, and no wonder: that’s where the readers are. Ander Monson’s quirky journal DIAGRAM (poetry, essays, and actual diagrams) reported forty thousand unique visitors per month in 2014. No print-only litmag could give a poem the viral power of Patricia Lockwood’s “Rape Joke,” which circled the Internet over and over after its appearance in The Awl_._ Web publications, in Monson’s words, no longer seem like “poems written on dry-erase boards”; they seem “as material, as real, as durable, as professional” as the print magazines that—supported by subscribers or by universities—carry on, from Bitch to the Yale Review. It’s not that we don’t need or read print mags so much as that we might not need many more of them—not when we can get so much (and kill fewer trees) thanks to screens.

The story of how little mags went digital can be found by reading through the first and the last few essays among the twenty-two in Morris and Diaz’s volume. You’ll find other stories, too, some of which Diaz and Morris may not quite realize that their book has told. Read their volume cover to cover, and you could get irked by the Oscar-night-style thank yous, and by the self-praise: “We have continuously brought critical minds and creative imaginations together”; Bitch “has interviewed … people we genuinely admired, love, and want to talk to”; and so on. You might also note the surprisingly weak correlation between operating a literary magazine and writing clear, cliché-free prose. Lee Gutkind, the editor of Creative Nonfiction, says he succeeded by “thinking out of the box with a worldview and marshaling the power of the people” as his journal “moved from idea to reality.” Alaska Quarterly Review, its editor says, “continues to serve as a frontline crucible,” perhaps melting down obsolete infantry.

And yet these aspects of the weaker essays reinforce the point that all of the stronger pieces makes: every issue of every litmag requires people to do “the copyediting, the layout, the negotiation,” as Carolyn Kuebler, of Rain Taxi and New England Review, puts it, “the planning and organizing and get-it-done work.” Such people may or may not write sparkling sentences, but if you yourself write sparkling sentences you have to depend on them—and you ought to respect them—if you want those sentences to get read.

Still, having a crack production team, elegant pages, and a balanced budget isn’t enough to get those sentences in front of readers: for a literary journal to succeed, now as in 1974, when Joyce Carol Oates and Raymond Smith launched Ontario Revie__w—or, for that matter, in 1802, when Francis Jeffrey and three of his friends launched Edinburgh Review, whose famously harsh (and long) review-essays examined the literary production of the day at greater length, and with more seriousness, than the magazines that had come before—you have to do something that hasn’t been done well before. You can use several different measuring sticks to say whether a litmag “succeeds”: longevity, financial stability, influence on new writers, number of readers, number of imitators launching journals very much like your own. But all these kinds of success come down to whether your journal brings something new to its scene.

It helps if you and your friends are actually creating a new kind of verse or prose—something that existing institutions and their standards of taste will not accept. Bruce Andrews calls his magazine L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, which ran from 1978 to 1981, a “mobile bandwagon, not a fortress or a monument.” Thanks to L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, and to its sister journals in D.C. and on the West Coast, anyone who takes contemporary poetry seriously now knows about the “language poets,” whose hard-to-read new styles rejected both capitalism and clear prose sense. Their early poetry—and their theories about it—could never have appeared in The New Yorker or Poetry back then (though they do now): they needed the space their own magazines could provide.

And their success shows why little magazines matter more, and work better, the stranger and newer their goals. A little magazine, as Jonathan Farmer, of At Length, explains, “depends on creating a community,” and that community has to have some raison d'être, aesthetic or ideological or ethnic or geographic or even generational: part of the point of the great online journal Illuminati Girl Gang, run by the alt-lit poet Gabby Bess, is that its poets and artists speak to, for, and about feminists who are barely out of their teens.

What a new litmag should not be is simply a farm team: we already have plenty of those. If you don’t have a particular aesthetic, a way of reading, or a kind of writing you want to promote, you might seek editorial experience or a venue for your design sense. Maybe you just want to boost your friends. (“Art, if it doesn’t start there, at least ends,” W. H. Auden wrote, “In an attempt to entertain our friends.”) Maybe you like having projects to share with friends (they may not be your friends after you fight about the cover for issue four). But why—other than personal acquaintance—would a famous writer with many other possibilities give you her work? Why would a reader who can choose so many other magazines choose yours?

If you do have defined goals or a clear aesthetic, then you’ve got a reason to attract writers and readers and donors who aren’t your friends—though they’re less likely to turn you down if they know you personally, at least a little. Keith Gessen says that n+1 started because “we were in New York, where things can take on a momentum of their own,” but he doesn’t address the source of that momentum; the least convincing of all the propositions in this volume is the idea that, thanks to the Web, it no longer matters where you live. The advantage of life in a cultural center has not vanished, though it has diminished. You can start a Web journal, publish your friends, and ask better-known writers for contributions, but it helps if you’ve met them; and, if you want to meet them, it helps if you live, or used to live, in Toronto or San Francisco or New York.

If you move away, you might end up at a university, teaching students how to run a journal, or at least having them read the submissions. Fiction and poetry magazines that last for more than a few years almost always end up leaning on academia, even if they began by attacking it; the notional sacrifice of independence is a small price to pay in return for a consistent source of interns and apprentices, a desk, an H.R. office, and a mailing address. But this kind of institutional support has been available most often for journals that fit well with one or another academic creative-writing program. Imaginative journals that do not—Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet (science fiction and fantasy), for example, or The Comics Journal (arguments and critiques of comics and graphic novels)—have found other ways to survive.

You can promote a taste or a genre (Creative Nonfiction), or a place or a demographic (Asian American Literary Review), or some combination (Callaloo, at first a venue for “African-American writers in the South”). Rain Taxi publishes almost nothing but book reviews and author interviews; At Length publishes, in its poetry section, only poems too long to fit most magazines. (So does Seattle Review.) These are all good reasons to start your own litmag. And they’re far from the only ones. A new journal needs a reason to exist: a gap that earlier journals failed to fill, a new form of pleasure, a new kind of writing, an alliance with a new or under-chronicled social movement, a constellation of authors for whom the future demand for work exceeds present supply, a program that will actually change some small part of some literary readers’ tastes. None of this has changed with the rise of the Web. Nor has the other big truth about little magazines which emerges from Diaz and Morris’s book, or from a day spent with anybody who runs one: it’s exhausting, albeit exciting, to do it yourself.

Stephanie Burt, a professor of English at Harvard, has written several books of literary criticism and poetry, including “After Callimachus,” with Mark Payne.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/06/whats-the-point-of-literary-magazines

What's the point of literary magazines?

Tuesday Nov. 5 2013It’s true that many cannot survive from sales – but this argument can be made about all art. Meanwhile, a growing enthusiasm for creative writing presents a tremendous opportunity for publishers

ike many people involved with little magazines, I was somewhat taken aback by Robyn Annear’s recent piece about our sector in the Monthly. Her assessment of literary journals felt, on the one hand, uncharacteristically mean-spirited and, on the other, so awkwardly assembled that even now I am still not certain I understand the argument.

Consider the following:

But what of the view, espoused by the Australia Council, that literary magazines are a mark of cultural vitality? Are they really all that stands between us and philistinism? In a word, no. There will always be literary magazines – by that or another name, on paper or in pixels – no matter what.

"Literary magazines do not stand between us and philistinism … because there will always be literary magazines". With the best will in the world, that makes no sense whatsoever.

Then there’s this:

Because there is for poets no equivalent of the Large Hadron Collider – a speculative venture supported by billions of dollars from world governments, with no certainty of outcomes that can be monetised or weaponised – literary magazines exist.

At least, that was my supposition as I assembled a pile of 10 Australian literary magazines for reading. How to account for these oddball miscellanies except as buffered delivery systems for that hardest to swallow of literary art forms? Truly, I still can’t say.

The weird negatives, the clumsy construction of that first line, the metaphors strained past the point of collapse: given these paragraphs introduce a piece chiding "oddball miscellanies" for publishing essays "knockabout enough to be blog-fodder", one wants to mutter something about pots and kettles.

Does this merely vindicate Muphry’s law, the adage warning that critiques of others’ editorial standards will invariably contain howlers of their own (yes, you can point out mine in the comments)? Perhaps so. But I wonder if there’s something else going on. Is it possible that an apprehension about literary journals cannot be argued intelligibly without acknowledging a deeper anxiety about literary culture, one too disturbing to be expressed coherently?

"I’ve dwelt a good deal on what motivates the contributors and funders of literary magazines in print," Annear says. "But what about readers? The fact is, there aren’t a lot of them."

One’s natural inclination is to respond defensively: actually, Overland’s subscriber base stands at a 30 year high; each paper edition of the journal reaches about the same number as most local literary novels; the print readership exists alongside the third of a million people who accessed the Overland website last year.

But that would be disingenuous. Basically, Annear’s right. Literary magazines do not reach a mass readership. Then again, neither does literature.

"To say that no one much likes novels is to exaggerate very little," writes Gore Vidal. "The large public which used to find pleasure in prose fictions prefers movies, television, journalism, and books of 'fact'".

Vidal was arguing that back in the late 1960s, well before the digital revolution presented an array of an entertainment options against which the literary novel – indeed, literary writing of any kind – simply could not compete.

On all sorts of measures, the most significant cultural production this year was not a novel, nor a play, nor even a movie. When Rockstar rolled out the latest instalment of its Grand Theft Auto franchise, it earned a billion dollars after three days on the market. All over the world, people took sick days to play GTAV. What other form inspires that level of devotion?

"Everyone knows that books have been getting the shit kicked out of them by movies and TV for many decades now," argued Todd Hasak-Lowy in the Believer a few months ago. Importantly, he wasn’t talking about sales: his point was that it had been a long time since a novel generated critical debate of the intensity (or, indeed, the calibre) spurred by the show Breaking Bad.

None of this is a secret. Everyone knows literary publishing in Australia rests on a very narrow audience. A famous commissioning editor once told me that her imprint relied more-or-less exclusively on "the three middles" – the middlebrow, the middle-class and the middle-aged. No, not all book buyers fit into those categories but they give you a working description of the readers who regularly attend festivals, keep up with the book pages and reliably buy new literary novels.

The Monthly piece discusses funding at some length, pointing out that many literary journals receive grants from the Australia Council and elsewhere. As Annear puts it in another peculiarly awkward sentence, "depending wholly on sales and subscriptions would seem to be no way for a literary magazine to thrive."

Now, the great bulk of funding received by literary journals goes directly to contributors (with Overland, the figure stands in excess of 70%). Because the journals operate on the smell of an oily rag, they provide a very cheap delivery mechanism for funds allocated to poets, fiction writers and essayists. Without state funding, the older magazines would probably still survive – but they would be far less able to pay their writers even the pittance that they now receive.

But that’s not the important point.

Yes, it’s true that many lit journals cannot survive from sales and subscriptions. But, once more, that’s an argument that can be made much more broadly.

The Age, the Sydney Morning Herald, the Guardian, the New York Times: all of them survive, in one way or another, on subsidies, either from trusts or from other more profitable parts of the corporation that owns them. In his new book Breaking News, Paul Barry quotes one of Murdoch’s editors: ‘There’s only one person in the world who run The Times, the New York Post and The Australian at a massive loss and that’s Rupert. If he died today do you think that News Corp would still own those papers in three years time? No way."

Even those newspapers that do make money have never done so from sales and subscriptions, with the crisis in the newspaper industry less indicative of a loss of readership than a collapse of advertising revenue.

If Murdoch subsidises his papers for personal political gain, quality literary publishing has often depended on proprietors with deep pockets, people prepared to absorb losses in the name of good writing. That, after all, is pretty much the Monthly’s story, with Morry Schwartz bankrolling its launch to the tune of a million dollars or so. Kudos to him for doing so – but it scarcely constitutes a viable funding model for those of us who aren’t real estate magnates.

That’s why, as I have argued elsewhere, writers and the left need to lose their obsession with the market. For a previous generation, it was entirely uncontroversial to argue that state support was necessary if the new technologies of radio and television were to reach their full potential. Such was the genesis of the ABC, now one of the most trusted institutions in the country.

Today, the internet offers extraordinary opportunities for writers and readers. But, in a typically capitalist paradox, its emergence has caused absolute devastation throughout the publishing and news industry. These crises will not be resolved by the market – and that’s why we need to start serious conversations about public models.

Anyway, that’s a debate for another day. Let’s instead look at another point that Annear makes: that "the absence of printed magazines – or literary magazines, full stop – would discommode contributors, and potential contributors, far more than it would readers."

Certainly, it’s true that a large proportion of those who subscribe to lit journals consider themselves writers. But I don’t see that as a problem. On the contrary, it seems to me that the extraordinary and growing enthusiasm for creative writing presents a tremendous opportunity for literary publishers of all sorts.

After all, a recent Australia Council study identified creative writing as a leisure time activity for a remarkable 16% of the population, with 7% working on a novel or short story and 5% writing poetry. In particular, writing courses are booming throughout higher education, in a context where many of the more traditional humanities are struggling. Surely that’s all to the good!

Annear’s concerned that creative writers seek publication for its own end, rather than as a means of communication. As she puts it:

The first step towards emergence as a writer must surely be to find something to say. Groping towards that goal may be what creative writing groups and workshops and university degrees are good for. It is one of the things that writing for yourself is good for. Getting older is good for it, too. But it oughtn’t to be what publication – at least, publication with a cover price – is for.

I quite agree with Annear that championing emergence for emergence’s sake is empty.

Yes, literary magazines must do more than provide space for new authors. They should be places in which writers articulate why they write, where contributors develop the particular aesthetic or political credos they think will take the culture forward – less ‘publish me because it’s my turn’ and more ‘publish me because I have something to say that’s not being heard’.

But, again, surely Annear’s argument applies more broadly.

If you look back through the 20th century, the emergence of the most significant little magazines invariably involved the production of a manifesto – a document in which the journal articulated the aesthetic or political stance that justified its existence. A credo goes with the territory: given the intense difficulty of keeping a lit mag alive, you need some sort of rationale to explain why you bother.

Overland, for instance, possesses a very clear and very recognisable identity. We do orient to emerging writers, with a variety of competitions and other opportunities. At the same time, we present those writers with arguments about the political and cultural context in which they are working, precisely to foster an attitude to writing that goes beyond getting one’s name in print.

In particular, there’s an obvious political orientation to the magazine so that, for better or worse, Overland publishes perspectives that would not otherwise appear. Can other publishers make the same claim? What about, say, the Monthly?

Obviously, the Monthly publishes some talented writers, many of whom express interesting opinions on important subjects. Yet almost all its contributors have regular access to other outlets. If the Monthly ceased tomorrow, what views would be silenced? Does it not, for the most part, present an entirely mainstream liberalism, of the kind you can find daily in the Fairfax press and elsewhere? Yes, Monthly articles can be more extensive. But that’s scarcely much of a manifesto – "we’re like the Age but longer!"

I don’t want this to be misinterpreted. I am not attacking the Monthly or calling for its closure; on the contrary, I am glad that it exists. I am simply saying that the issues Annear raises are equally relevant for those outside the small press sector.

Indeed, precisely because little magazine are little, they tend to have addressed such questions more openly than their bigger counterparts, articulating at least some kind of argument about where they want to take the culture.

With that in mind, consider how that Monthly piece concludes. The final paragraph refers back to a pieceby Simon Tedeschi, a concert pianist recently published in Seizure. Annear writes:

I felt, at the end of [reading all the journals], like Tedeschi leaving a Frenzal Rhomb performance (his first) after just four songs. ‘I know I’m being rude,’ he wrote, ‘but … I desperately need to get back and listen to Bach.’

I haven’t read the Tedeschi essay and would like to think that it’s not as much of a troll as that description makes it sound (asking a classical musician to assess a punk band seems as useful as sending a trance DJ to review Beethoven – or, perhaps, polling some fish as to their views on bicycles).

But let’s leave that aside. Actually, during his lifetime, Bach was recognised primarily as a performer. Why? Precisely because his peers dismissed his compositions as incomprehensible! The church that employed him as an organist reproved him for having made "many curious variations in the chorale, and for having mingled many strange tones in it, and for the fact that the congregation has been confused by it".

One might think, then, that, in a discussion of lit journals (publications that should provide a home for the marginal, the experimental and, yes, the unpopular), Bach makes a pretty good witness for the defence, a salutary reminder that initial responses provide no necessary measure of lasting aesthetic worth. Yet he’s enlisted to make the opposite case. In Annear’s argument, Bach stands for the canon: the classical master against whom the talentless punks contributing to little magazines are judged and found wanting.

This, I would suggest, is not a coincidence.

With its small, ageing and often aesthetically conservative readership, literary publishing faces an obvious pressure to reverse Brecht, to favour the good old things over the bad new ones. The clash between Bach and Frenzel Rhomb illustrates the tendency perfectly: an ideal metaphor for the reassuring assertion of conventional taste and a hostility to the new, the raucous and the unexpected.

If it’s vacuous to simply champion novelty – to publish emerging writers for the sake of publishing emerging writers – it’s equally inane to declare yourself in favour of "quality". Pinning your colours to "new writing" might risk an empty formalism (why should the new be any better than the old?) but if you’re merely presenting "good writing" you’re accepting as given that which you should be seeking to define.

Quite obviously, in the current context, where publishing’s so commercially dependent on such a narrow audience, an untheorised "good" will invariably mean "that which a middlebrow, liberal readership already likes".

For a glimpse of where that ends, we need only consider contemporary classical music, a form in which audiences are more or less overtly hostile to new composers of any kind. "Even before 1900," Alex Ross explains, "people were attending concerts in the expectation that they would be massaged by the lovely sounds of bygone days … The music profession became focused on the manic polishing of a display of masterpieces."

Why should I listen to new music when I could be hearing a composer from the eighteenth century, one I already like? Or, alternatively, why should I buy a new book when I have a perfectly good one at home?

Literature hasn’t reached that point – of course it hasn’t! – but any art form that allows its demographic to slowly narrow runs an obvious risk of cultural stagnation. The Annear piece does, I think, articulate some of the genuine difficulties facing the literary sector, albeit in a confused way. But these are problems that face all of us, not merely literary journals.

The solutions are not obvious. But if little magazines enjoy a certain freedom from market pressures, I’d like to think that makes them a space where we might start looking for answers.

Jeff Sparrow is the editor of Overland, where this piece was first published

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Days ago = 2849 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment