|

| https://uberscribbler.com/hireme/social-media/ |

Here's a really long and really great article by Jay Owens, whose @hautepop newsletter

is among my very favorites.

FROM -

https://medium.com/s/story/post-authenticity-and-the-real-truths-of-meme-culture-f98b24d645a0

The Age of Post-Authenticity and the Ironic Truths of Meme Culture

From fake news to our overly curated Instagram feeds, “authenticity” seems to be over. What are our new vectors for talking truth?

1. Media isn’t really real

In the last couple of years, fakery seems to have accelerated.

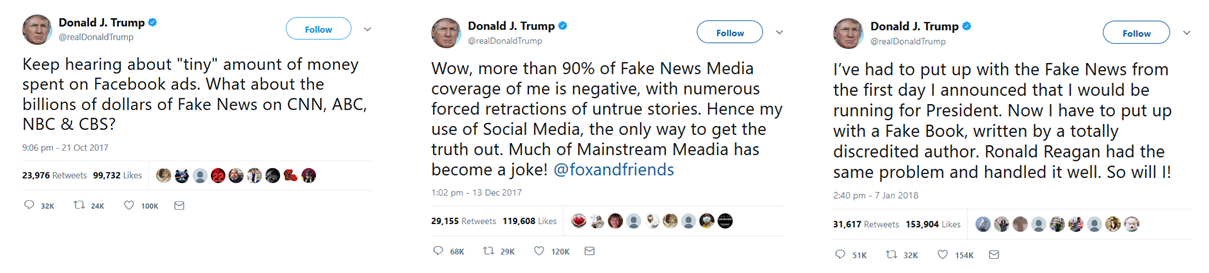

The term “fake news” appeared out of next-to-nowhere in November 2016.

|

| Source: Google Trends |

The press has published myths, falsehoods, and exaggerations for about as long as there has been a press, and even the term “fake news” dates back to the 1890s, the Merriam Webster dictionary reports. Lying is, surely, as old as humanity.

But the term has twisted. Fake news, as its been used in the last 18 months, doesn’t really mean fake in the conventional sense of the word — as in unreal, incorrect, or false news. As used by the President of the United States, the most mainstream and fact-checked of news media is fake if he disagrees with it. The term means something more like troublesome news, or “news I vehemently disagree with, and wish to discredit.”

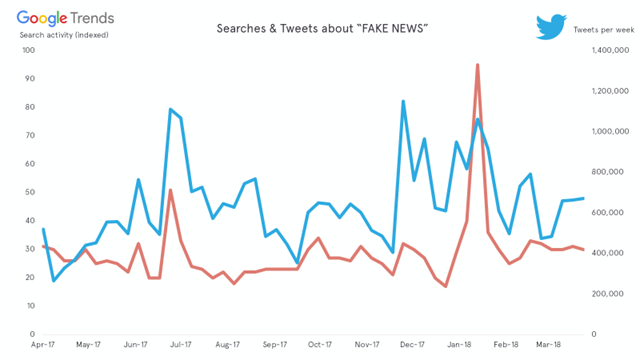

The President helped spur 29 million tweets about fake news in the last year, keeping the topic ever-present in public discourse.

|

| Sources: Google Trends and Pulsar Trends |

Meanwhile, in the U.K., slapping the label of fake news on anything becomes a political point-scoring exercise, as demonstrated in headlines such as: “Theresa May’s ‘fake news unit’ announcement has itself been branded ‘fake news’”. (Your boy Kafka would be proud.)

The work of making real news — the fact-checking and triangulating processes by which news organisations ensure their coverage is accurate and uphold professional principles of integrity — journalists talk about continually on Twitter. Yet is the message getting through?

Public trust both is and isn’t holding up.

Kantar’s 2017 Trust In News survey finds that people still believe in the principle of journalism: Across the U.S., U.K., France, and Brazil, 73 percent of people polled agreed that “quality journalism remains key to a healthy democracy.” The reputational impact of the fake news issue has been predominantly borne by digital and social media channels: 58 percent now trust social media coverage of politics and elections less and 41 percent trust online-only news sources less. Traditional television and print media channels have held up comparatively well.

However, the statistic to remember is that only slightly more than half (56 percent) believe what they read overall is true “most of the time.” The principle of a shared factual reality among the general public has become tenuous, and cannot be taken for granted.

Last month, an anonymous academic posted to Reddit, saying: “I’m a college philosophy professor. Jordan Peterson is making my job impossible.” They report how a minority of students who have been reading & watching “internet outrage merchants” come into class no longer merely disagreeing with some of the ideas taught — remarking “That I’m used to dealing with; it’s the bread and butter of philosophy” — but newly angry, deeply hostile, and believing in complete fabrications about what feminist or postmodernist or Marxist philosophy entails. “To even get to a real discussion of actual texts it takes half the [class] time to just deprogram some of them.”

As technology and society researcher danah boyd pointed out at SXSW Edu this year, attempts to increase media literacy in schools can often backfire. Examining the credibility of a Fox News article in class risks being perceived by working class or evangelical youth as an “elite” attack on their values. Teaching young people to make sense of the information landscape without exacerbating distrust is, boyd fears, very difficult: “When youth are encouraged to be critical of the news media, they come away thinking that the media is lying,” says boyd.

In 2004, a previous Republican presidency seeded the concept of “reality-based community” into the common consciousness,, a term meant as pejorative, to criticize political “opponents for limiting their vision to the way things were, rather than including what the Administration’s actions made possible.”

“We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality,” an unnamed Bush-era official, generally understood to be Karl Rove, said.

So this present state of things isn’t really new. Writer Kurt Andersen dates the rise of this present “truthiness” back to the 1960s, and the rise of a new mode of thinking: “Do your own thing, find your own reality, it’s all relative.” And yet.

2. Technology is warping reality in new ways

The post-authenticity of fake news isn’t solely a technological or media problem, but a social one, symptomatic of declining trust in a shared civic project. Nonetheless, new media technologies really aren’t helping.

In the last year or two…

…Technologies have become available to falsify people’s voices, so that you can make them say anything you want. In 2016, Adobe released a tool, VoCo, which only needed 20 minutes of listening to someone’s voice before being able to co-opt it. In May 2017, Lyrebird, a Montreal-based AI startup, claimed to be able to synthetically mimic any person’s voice based on just 60 seconds of speech.

…Faking video has also become accessible. In March 2016, researchers from the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, the Max Planck Institute for Informatics, and Stanford University presented Face2Face, a novel approach for creating fake videos — e.g., making Putin smile, or George W. Bush appearing to lip sync to ridiculous material. Through capturing the facial expressions of a source actor on a webcam and using facial mapping, they’re able to manipulate and re-render a YouTube video photorealistically.

The Face2Face team note that “computer-generated videos have been part of feature-film movies for over 30 years. […] These results are hard to distinguish from reality and it often goes unnoticed that the content is not real.” What’s new is that the technology is newly mass-accessible: now, “we can edit pre-recorded videos in real-time on a commodity PC.” (Source: Matthias Niessner, YouTube)

…Where video goes, porn is first to take advantage. In December 2017, Samantha Cole of Motherboard reported that “AI-Assisted Fake Porn Is Here and We’re All Fucked.” She reports how a Redditor by the name of deepfakes worked out how to combine celebrity facial images from Google image search, stock photos, and YouTube videos with porn videos, using open-source, neural-network, ‘deep learning’ library Keras and TensorFlow.

A month later deepfakes turned the process into an app and Vice reported that “We Are All Truly Fucked,” as the face-swap porn trend swept Reddit. It got banned, but, you know, that horse had already bolted.

…Various smaller events, too. The ongoing march of fake social media followers and fake “likes,” as reported most recently in the New York Times’ snazzy longreads investigation “The Follower Factory,” a somewhat late-to-the-party, but nonetheless welcome, dig into the entirely fictional world of celebrity and influencer social media metrics. More fake metrics over on TripAdvisor, too, as Oobah Butler of Vice made his garden shed the #1 rated restaurant in London.

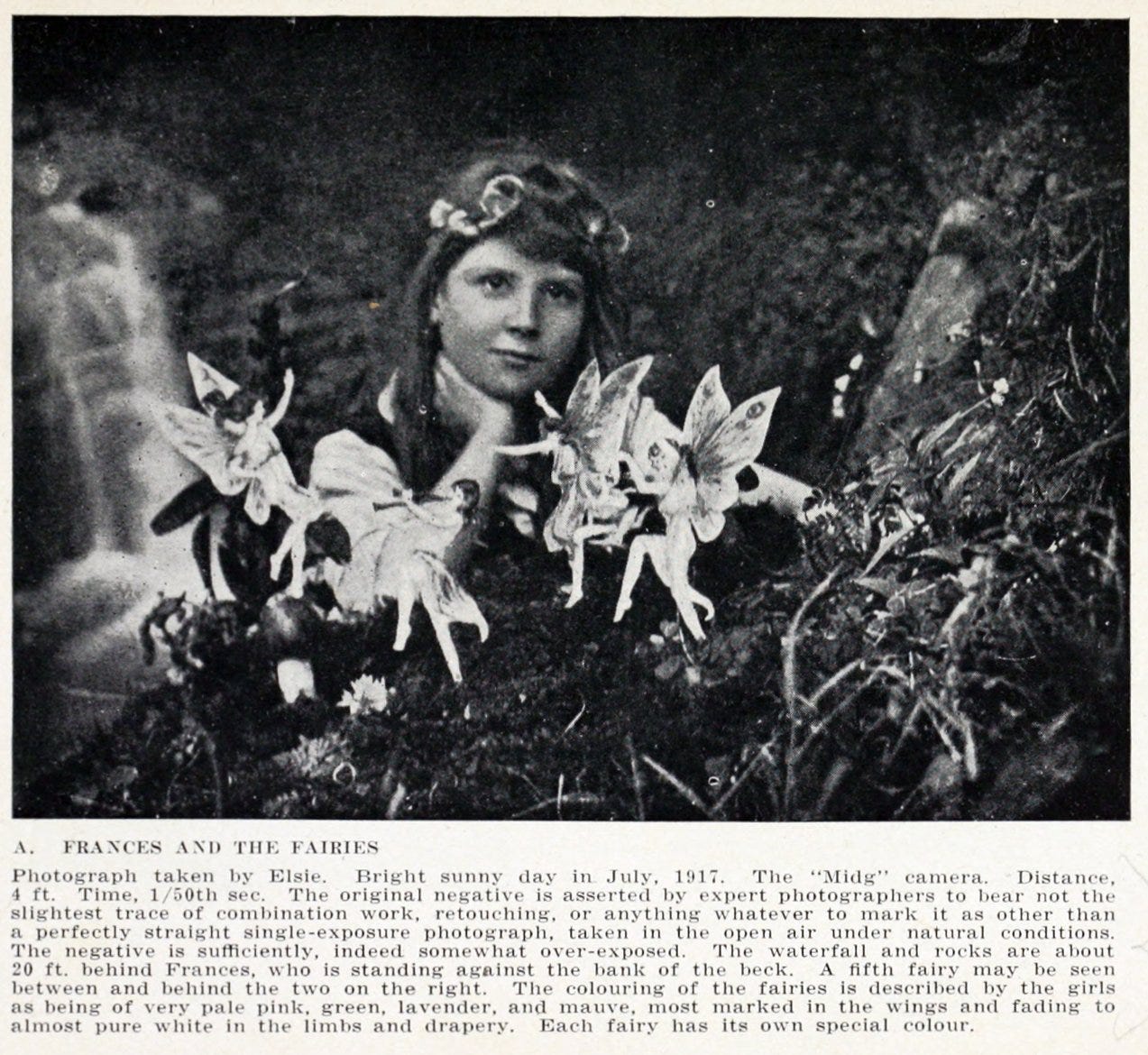

Again, none of this is exactly new: in 1917, two young girls went down to a stream at the bottom of a garden in Cottingley, England, and took some photographs of fairies which then spread across the world as factual evidence that fairies were real.

|

| Fake fairies. Image credit: Kristian Nordestgaard via flickr/CC BY 2.0 |

Yet, something is up. Something in culture has shifted, quite recently, and now the world is different: the pace and extent of fakery has accelerated. It’s not just happening in media; it’s happening in pop culture, too.

3. In the fashion industry, authenticity imploded around 2015.

Authenticity was the defining value of the late-stage hipster.

How the hipster transformed from trucker-cap-clad, 2000s-era, nu-rave machine to bearded, artisanal, flannel shirt connoisseur is recorded in various lifestyle magazines — perhaps best, and most visually, in Paste Magazine.

Though, seeing how as this is my generation we’re talking about, I might feel inclined to comment how we just grew up and slowed down a bit. (Perhaps we can attribute some of this to the British government making mephedrone — the “white powder that smells faintly of cat piss [which] defined the U.K.’s party scene from 2008 to 2010” — illegal.)

Rewind to 2010. It was at this time, as smartphones and digital media took over our lives, that the dominant aesthetic of middle-class consumption — fashion, interior decor, and lifestyle — went the other way: rough-hewn, and wholesome. Authentic. Do you remember the beards? The flannel, the workwear, the artisan everything: coffee, bread, burgers? Ostentatious unpretentiousness abounded: cocktails in mason jars, wine in tumblers, and ridged, deeply-textured wooden tables and walls. Flower crowns and neo-boho festival fashion.

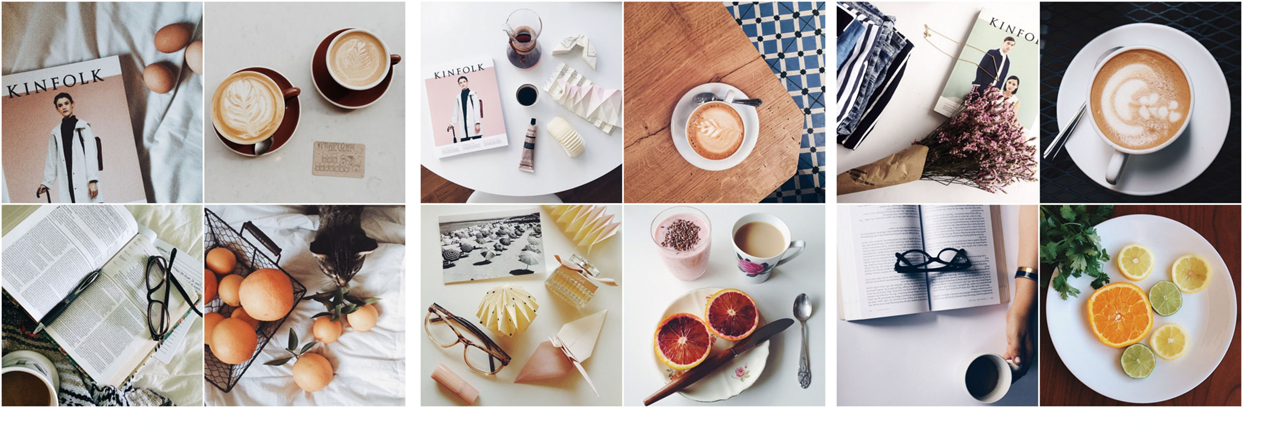

Driving this trend was a small magazine — print, of course, published on heavyweight, matte paper stock — out of Portland, Oregon, called Kinfolk. Its visual aesthetic spread far and wide:

|

| L-R: Instagram users @MaryHoagland, @UpTheWoodenHills, @NuanceAndBubbles Photo coordination credit: Summer Allen. |

Writer Summer Allen noticed just how much of a template this look was becoming, and began to chronicle its spread on her tumblr, The Kinspiracy:

“I started the The Kinspiracy tumblr after I noticed a pattern emerging from dozens of Instagram users — my own personal Beautiful Mind moment. It was suddenly so clear: Every account cultivating that Kinfolk look seemed to follow a specific formula. Every account had a photo (or several) of the following: A latte with a foam leaf design, a fresh piece or two of citrus, a glimpse of a pair of small feet — often in a well-worn pair of boots — an ice cream cone, weather permitting, some glasses here and there, twine, the occasional fixed-gear bike. And always, inevery damn account, Kinfolk.”

— “Wood, Citrus, Lattes, Feet, Twine, Repeat: The Kinfolk Kinspiracy Code” by Summer Allen, Gawker, March 2015

The “authentic” look wasn’t just shaping people’s Instagram feeds, but also real-world spaces and places, too, in a feedback loop between social media and IRL that journalist Kyle Chayka called “AirSpace”:

"It’s marked by an easily recognisable mix of symbols — like reclaimed wood, Edison bulbs, and refurbished industrial lighting — that’s meant to provide familiar, comforting surroundings for a wealthy, mobile elite, who want to feel like they’re visiting somewhere “authentic” while they travel, but who actually just crave more of the same: more rustic interiors and sans-serif logos and splashes of cliche accent colours on rugs and walls.”

— “Same old, same old. How the hipster aesthetic is taking over the world” by Kyle Chayka, The Guardian, August 2016

Later, Chayka was blunter relaying his frustrations — tweeting in October 2017 that “‘authenticity’ is the plague of the 21st century”,” in a thread detailing the cynical falseness of so many of its iterations.

"Authenticity" is the plague of the 21st century— Kyle Chayka (@chaykak) October 17, 2017

The contradictory appeal of AirSpace was best summed up by artist and designer Laurel Shwulst, in another feature by Chayka: “It’s funny how you want these really generic things but also want authenticity, too.”

The authentic aesthetic is too clearly a facsimile, too obviously a template rolled out by the operations directors of VC-funded, millennial pink-branded startups and Airbnb “superhosts” putting the same framed inspirational quotes in every resident-displacing condo. Airbnb rebranded in 2014 with a campaign about how you can “belong anywhere,” a profoundly inauthentic claim that strips belonging of all meaning.

|

| All hipster coffee shops have the same stools (source: Google image search) |

Around 2015, there was a wave of articles about how “the hipster” was, finally, dead as a cultural archetype and authenticity, as a cultural value, expired along with it:

“The typology has become a caricature and the terms once associated with it — craft, artisan, making — have also become cartoonish. When McDonald’s boasts about artisanal chicken (complete with “artisan chicken” and “artisan roll”) you know the message has gone awry.”

— “The hipster is dead, let’s start an anti-authenticity movement” by Daniela Walker, Campaign, Sept 2015

What came next? Minimalism was one answer from marketers , but that mood didn’t last. In Spring 2016, designer Demna Gvasalia shocked the fashion press with bootleg “anti-fashion” at Vetements , selling meta-referential hoodies, DHL-branded T-shirts, and reworked secondhand jeans for hundreds, and some thousands, of Euros. Meanwhile, in the hipper echelons of design, we’re back to postmodernism, with 1980s Memphis Group aesthetics and terrazzo replacing Insta’d-out white marble — if the pages of Elle Decoration and graphic design of Chayka’s journalist co-op, Studyhall, is anything to go by). Authenticity and the desire to focus on the perceived, more-real “essence of things,” is no longer in vogue, and clever references are.

Something similarly playful is happening, in how the post-millennial Generation Z present themselves online.

4. Generation Z are pioneering post-authentic social media

Back in 2010, Mark Zuckerberg made the case for the single, real-name Facebook account as the “authentic” way to do social media, and sought to impose this model of self-presentation on hundreds of millions of users, with Facebook’s controversial (and now partially rolled-back) “real names policy.”

But authenticity became performative, as we started to speak to audiences of hundreds and thousands beyond our “real” pool of friends and family, and likes and follower counts trained us to create the kinds of content that would be most popular, over realistic depictions of our day-to-day. Our Instagram feeds professionalised: the quality of photography improved, the captions were strategically wittier. The relationship to our real lives became more complicated.

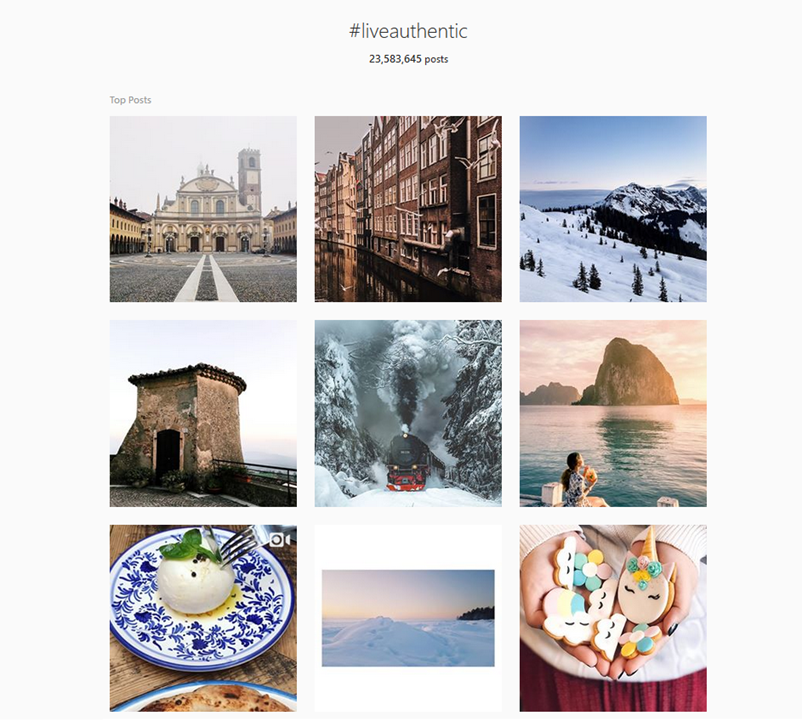

The ur-point of this, for me, is the #liveauthentic hashtag on Instagram: a compendium of the most Kinfolk-perfect depictions of an enviable foodie, travel, Rise-filter-tinted lifestyle complete with ‘golden hour’ glow.

Meanwhile, young people were reporting that looking good on social media was stressing them the hell out.

A survey from the British charity Girlguiding in the U.K. last year found that teenage girls weren’t just seeing the same social media risks as their parents, as a place where they might be threatened by bullying and “stranger danger.” Instead, for girls aged 17 to 21, the second biggest worry online was the pressure of “Comparing myself and my life to others.” Their biggest concern tied for fourth place? “How I look in photos.”

Social media has, after all, dramatically changed the field of social comparison, from operating mostly at the transient, real-world social scale of a few hundred people around you at your school and in your neighbourhood, to one that’s media-scale, global and permanent. Eric Herber, then a 17-year-old in high school, wrote:

“When I post a photo on Instagram I know that just about every person I am connected to in the real life will see my photo, decide whether or not to like it, and then judge me subconsciously.

Because of this, Instagram is seen as a huge stressor for many teenagers.

Your Instagram defines who you are.”

— “Finstagram: The Instagram Revolution” by Eric Herber, Medium, February 2015

Teenagers, being young and adaptable, have modified their social media behaviours to fit this new landscape accordingly.

An 18-year-old American high school student, interviewed by journalist Justine Harman, details the heavily-strategised social media management playbook she and her peers use:

“I would never post twice in one day because if I am expecting to get 200 likes on a picture, I have to post sparingly.

First you have to edit the picture, make sure no one in your friend group is already posting it, send it to your friends for approval, think of a clever caption, and then post it at a time of day that will hopefully afford you the most amount of likes.

Yes, it’s insane. But this is what girls do.”

— “The Crazy Way Teens Are Hiding Their Imperfections Online: Finstagram” by Justine Harman, Elle.com, July 2015

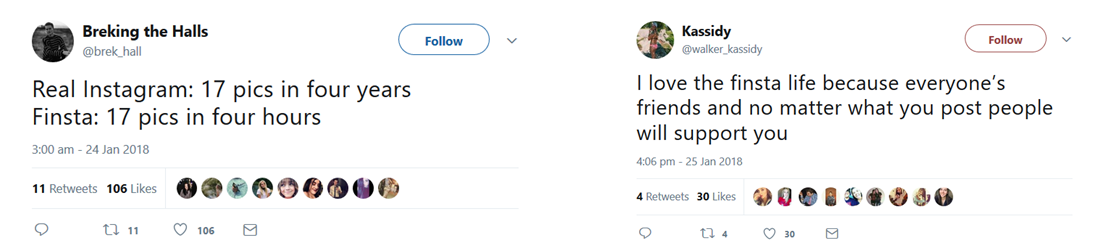

As a result, enter Finstagram.

What is it? It’s fake Instagram, for trash pics and the outtakes reel of your main, hyper-curated Instagram account.

|

| Instagram @HanHoop, via Mic.com |

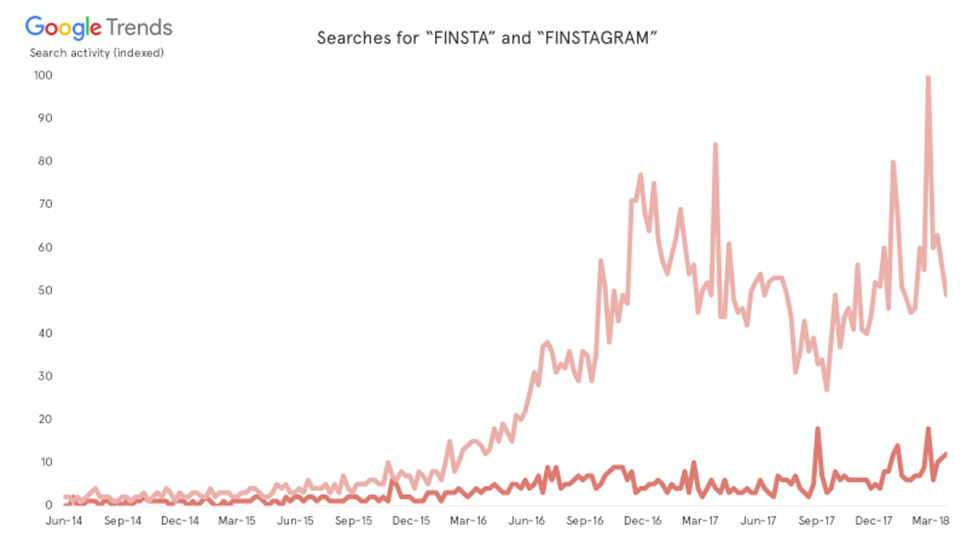

Finstagram has been a thing since, ah yes, January 2016: coincidentally or not, just after hipster “authenticity” died.

|

| Source: Google Trends |

Freed from having to maintain a singular, authentic, official identity, it turns out young people feel they can be a lot more real on their fake accounts.

Snapchat offers the same promise: ephemeral social media. It’s digital “safe space” in the real sense of that concept: setting boundaries and expectations in order to make difficult things — here, your imperfect, unfiltered self — easier to share.

5. The Meme Generation

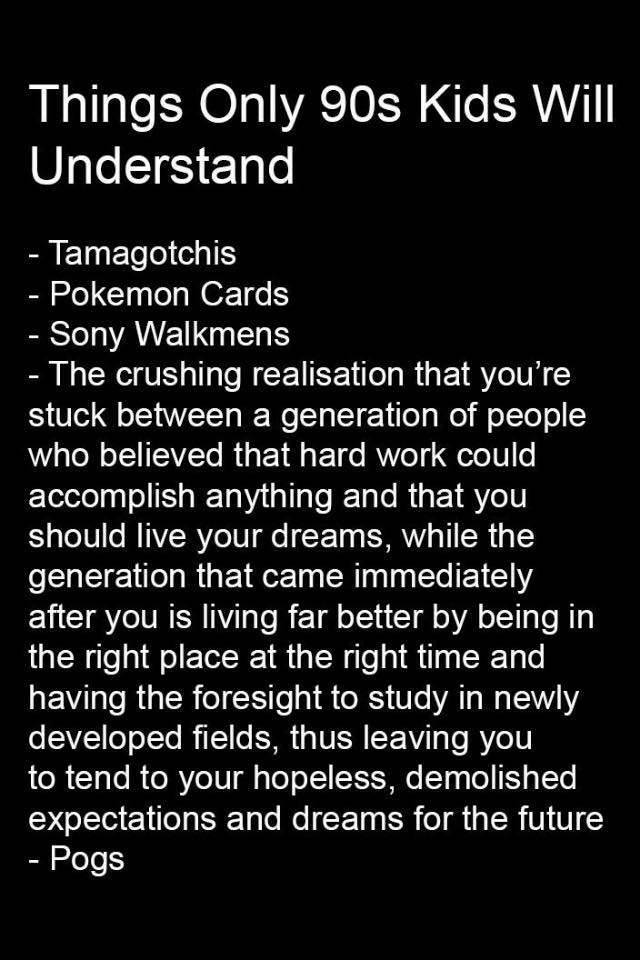

“Generations” are a bullshit marketing concept, right? Except all of us looking at the remarkable teenagers of Parkland High School and their astonishing media campaigning for gun control are also aware that something’s remarkably different about kids today.

For the last two or three years I’ve been doing a bit of work for a tech client in regards to understanding millennials and Generation Z: what are they doing, how are they different, and what makes them tick. For Generation Z — born in 2000 and onward — there are two interesting, seemingly opposite cultural tendencies at play.

On the one hand, they’re the sensible generation. Every measure of risk-taking behaviour is down, across the U.S. and Europe: drinking, smoking, drug use, early sexual activity, and teenage pregnancy. Spurred by the prospect of massive educational debt, they try harder in school and have heartbreakingly modest and, well, sensible aspirations for their future lives.

On the other hand…

Let me introduce you to a cultural goldmine. In September of last year, an AskReddit thread posed a question: “Teens of Reddit, what is considered cool right now?”

The answers are brilliant:

“17 here. The word “lit”, trap music, being “THICC”, Vans, Converse, Gucci flip flops, chokers, crop tops, ripped jeans, bomber jackets, Kendrick Lamar, acrylic nails, going to the gym, athletic clothing, taking aesthetic pics of your dog or yourself or both together, being “relationship goals”, grinding at school dances, prom, being confident, being smart, being artistic, ooh and MEMES!!!!!

idk what else but those are the basics lol.”

— Majestichuman, Reddit.

The most upvoted answers stressed irony as a fundamental orientation:

Youth culture today, in two words: practicality and memes. Seriousness, and also taking nothing seriously.

Teenagers may be shifting away from posting Facebook status updates — partly because Facebook is where your mum and aunties hang out online — but one part of Facebook is thriving: Groups. Zuckerberg emphasised Groups in his “Building Global Community” strategy last year, with a putatively civic-minded goal to “strengthen people’s online and offline connections.” But he probably wasn’t thinking of groups like these:

Frequented mostly by an audience under 25, many of these groups exist as a space to share funny, ironic, meme-y content. Roots lie in what was called Weird Facebook — as documented by Jordan Pedersen in 2014, the group Shit Memes then had 30,000 followers, and was one of the bigger groups around. Prior to that, internet meme culture in the period 2008–2012 was being heavily driven by 4chan /b/ board, as Whitney Philips notes in her 2015 book “This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture.

But in the last couple of years, Facebook’s meme groups really took off. We started seeing articles like “The Rise of Weird Facebook: How the World’s Biggest Social Network Became Cool Again (and Why It Matters)” (Hudson Hongo for New York magazine, February 2016) and “The Future of College Is Facebook Meme Groups” (Paris Martineau for New York magazine, July 2017)

College and university meme groups are particularly interesting spaces, because here the seriousness and the “memeyness” of the present generation of youth culture intersect, to often startling degrees.

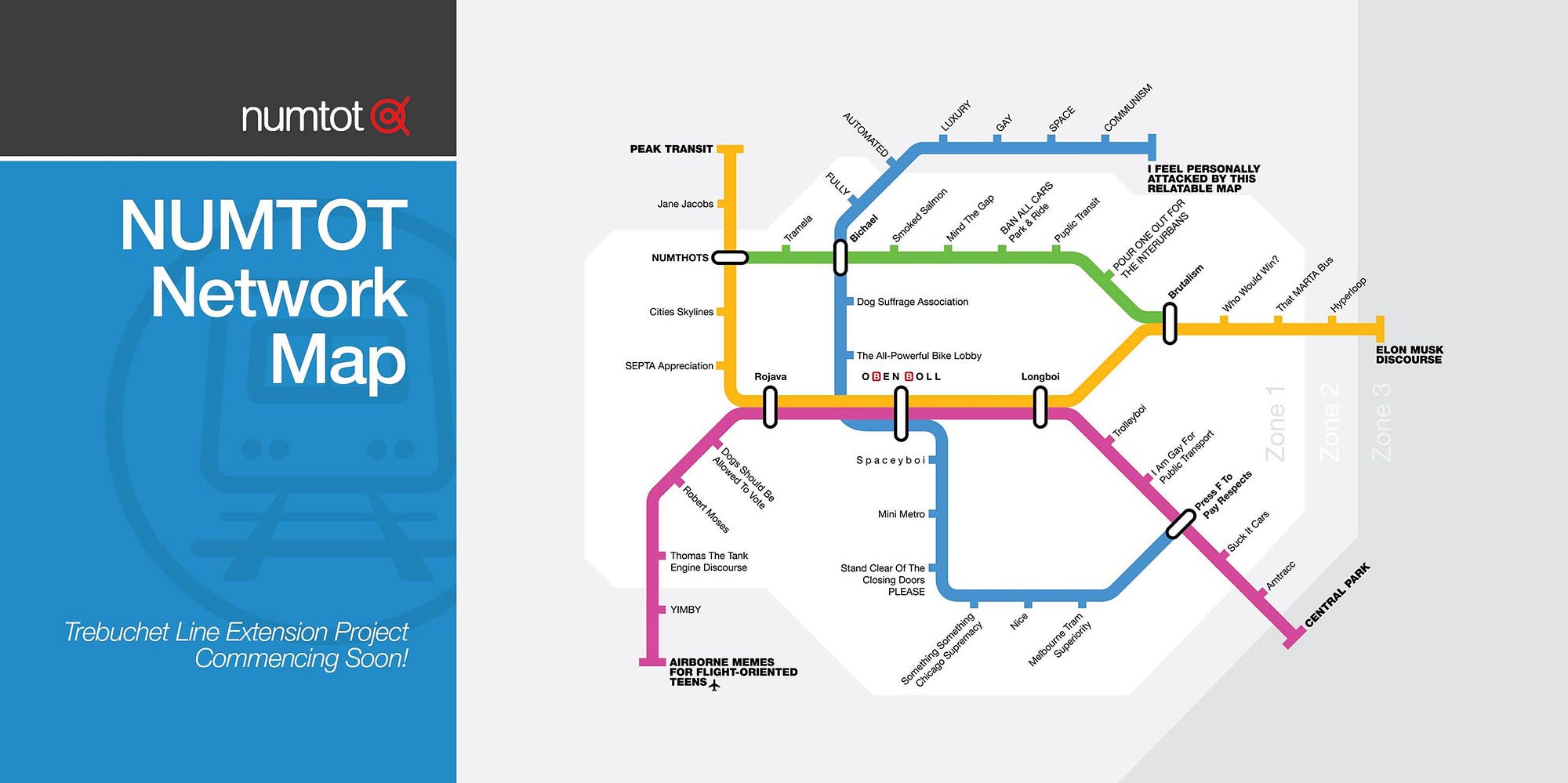

Sometimes it’s simply very educational, such as in groups like NUMTOTs: New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens, which boasts over 70,000K+ members). This group mixes an irrepressible repurposing of other internet meme forms, from dog meme vocabulary where everything is a “boi” — “Sad reaccs only for this r e p l a c e m e n t b o i” for a replacement bus service meme — with contemporary meme formats such as this week’s “American Chopper” meme made into a debate about Shinkansen vs. Maglev trains, alongside serious discussion about the needed reforms to the transportation systems and overall urban planning of American cities.

|

| NUMTOTs’ mapping of their intersecting obsessions, from peak transit to Elon Musk. Design credit Mitchell Sheldrick |

One testimonial notes: “I joined this group expecting memes and all I got was the equivalent of a bachelor’s in urban planning.”

But teenagers are using humour and irony — through memes — to find ways to face and discuss deeper stresses and anxieties, too.

My alma mater, the careers-obsessed cultural desert that is the London School of Economics, has a good line in memes which are almost entirely about the pressures students face in their studies and in trying to secure a good job (read: banking or consultancy) after graduation.

|

| Source: Facebook Group Robust Memes for LSE Teens |

The LSE Memes admin offers barbed benedictions to its anonymous contributors: “May they become one of our top banking lizard overlords,” or“May their hourly consultancy rate collapse a small country’s economy,” and“May she get an unconditional offer from Rothschild so none of this matters.”The irony here is complex, capturing the students’ ambitions, doubts, and critics, all at once.

Meanwhile, groups like Nihilistic Memes (1.9M followers) and Dank Memes(901K followers) are some of the biggest in Facebook, trafficking in — again — a kind of doom-laden empathy:

|

| Source: Facebook Group Nihilist Memes |

Reporter Paris Martineau interviewed some of the founders of college meme groups for New York magazine last year. The admins emphasise the empathetic function of the communities they have created: “My friends and I always say that memes come from a place of stress and anxiety,” notes Ephraim Sutherland, co-founder of Yale Memes for Special Snowflake Teens.

“Before the page, I had never seen anyone get together and talk about these issues,” Tril of UC Berkeley Memes for Edgy Teens recalls. “Now, I feel like people aren’t afraid to talk about them out in the open.”

So through humour, exaggeration, and irony — a truth emerges about how people are actually feeling. A truth that they may not have felt able to express straightforwardly. And there’s just as much, and potentially more, community present in these groups as in many of the more traditional civic-oriented groups Zuckerberg’s strategy may have had in mind.

But why memes?

The formal properties of the meme make it a particularly effective format for delivering an indirect payload of empathy.

A major vector in meme content in the past couple of years has been “relatability” — from the Common White Girl (@girlposts) Twitter account celebrating the small failings of the everyday basic bitch (though she’s now, er, suspended for “fake or artificial interactions”), to reaction GIFs turning particularly expressive gestures (particularly from black female celebrities, Laur Michele Jackson notes) into reusable, quotable forms. In consuming these memes — in liking and sharing — the social media user is participating in a moment of commonality. They’re saying, “I am like this too.” These memes are predicated on a recognition of common human similarities.

Meme formats — from this week’s American Chopper dialectic model to now classics like the “Exploding Brain,” “Distracted Boyfriend,” and “Tag Yourself” templates — are by their very nature iterative and quotable. That is how the meme functions, through reference to the original context and memes that have come before, coupled with creative remixing to speak to a particular audience, topic, or moment. Each new instance of a meme is thereby automatically familiar and recognisable. The format carries a meta-message to the audience: “This is familiar, not weird.” And the audience is prepared to know how to react: you like, you respond with laughter-referencing emoji, you tag your friends in the comments.

The format acts as a kind of Trojan horse, then, for sharing difficult feelings — because the format primes the audience to respond hospitably. There isn’t that moment of feeling stuck over how to respond to a friend’s emotional disclosure, because she hasn’t made the big statement directly, but instead through irony and cultural quotation — distancing herself from the topic through memes, typically by using stock photography (as Leigh Alexander notes) rather than anything as gauche as a picture of oneself. This enables you the viewer to sidestep the full intensity of it in your response, should you choose, but still, crucially, to respond). And also to DM your friend and ask, “Hey, are you alright?” and cut to the realtalk should you so choose to.

And so a space is created, to talk about being stressed and overwhelmed and unsure of the meaning of anything we do — a space which is, I believe, more open than it has been in the past. As the moderator of UC Berkeley Memes for Edgy Teens says, this “gets the conversation going, as I don’t think it would have even started without it.”

Memes help people speak truths.

6. What does authenticity mean, anyway?

“Thrown, in spite of myself, into the great world, without possessing its manners, and unable to acquire or conform to them, I took it into my head to adopt manners of my own, which might enable me to dispense with them.”

— Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Confessions”

The concept of personal authenticity arises as part of Enlightenment rationality and a new, distinctively modern, conception of the self. Rousseau argued that authenticity is diminished by the need for the esteem of others; one’s guide to conduct in life should come not from social pressures or external rules (e.g. the Church), but rather a source within — the sovereign, rational individual.

Twentieth century philosophers — Sartre, Heidegger — recognised that this was perhaps a little more difficult than Rousseau claimed: the external world and its influences is inescapable and not straightforward to slough off, and nature and society shape us just as much as our own choices. And so authenticity must always be negotiated in complex interdependency with its opposite — that is, you were never really authentic in the first place.

That tension is what meme culture is negotiating: these unexpected, witty truths emerging through the most inauthentic, borrowed, or stolen stock content possible.

Because people still want to tell the truth about their lives and the world — absolutely nothing has changed there.

What is changing, I argue, are the cultural formats people are using for discussion — the carrier waves for this signal. This is where “authenticity” isn’t a useful claim any more, having been wholly co-opted and commodified into its opposite. Culture and the way we communicate — shaped by media affordances — have become more complex, ironic, and multi-layered than that.

It turns out, even people who share fake news stories are trying to tell a kind of truth too.

At SXSW Edu this year, technology researcher danah boyd argued that we’ve been rather uncharitable in our analyses of why people share fake news. The assumption is that people really believe the claims they share — that is, they’re ill-informed; that is, they’re stupid. It turns out not to be quite so simple:

“Yet, if you talk with someone who has posted clear, unquestionable misinformation, more often than not, they know it’s bullshit. Or they don’t care whether or not it’s true. Why do they post it then? Because they’re making a statement. The people who posted this meme [shown below] didn’t bother to fact check this claim. They didn’t care. What they wanted to signal loud and clear is that they hated Hillary Clinton. And that message was indeed heard loud and clear. As a result, they are very offended if you tell them that they’ve been duped by Russians into spreading propaganda. They don’t believe you for one second.”

— “You Think You Want Media Literacy… Do You?” by danah boyd, March 2018

|

| Source: Truthfeed.com (lol), November 2016 |

The people sharing this story are seeking to tell a kind of moral truth through metaphor and cultural quotation (the person shown in the picture is in fact performance artist Marina Abramović). Not entirely unlike our meme-ing teens on Facebook.

What I’ve sought to argue in this essay, then, is that we are indeed living in an a strange, surface-centric moment in popular, digital culture right now — where the original “essence of things” has indeed become somewhat unfashionable (or just less entertaining). Social and media technologies, optimised for the diffusion of highly emotive, reaction-generating content, encourage a rapid trade in attention-grabbing ideas over slower-burning systematic, contextualised thinking.

Yet, even as authenticity, both as a claim and an aesthetic feels outdated, deeper forms of realness in our communications still persist. People are still seeking to communicate their deepest personal truths: their values, hopes, and fears with each other. In sharing media, we’re still creating community.

Nonetheless, the kind of truth in play is changing form: emotional and moral truths are in ascendance over straightforward, factual claims. Truth becomes plural, and thereby highly contested: global warming, 9/11, or Obama’s birthplace are all treated as matters of cultural allegiance over fact, as traditionally understood. “By my reckoning, the solidly reality-based are a minority, maybe a third of us but almost certainly fewer than half,” writer Kurt Andersen posits. Electorates in the U.S. and Europe are polarising along value-driven lines — order and authority vs. openness and change. Building the coalitions of support needed to tackle the grand challenges we face this century will require a profound upgrade to our political and cultural leaders’ empathic and reconciliation skills.

So perhaps to say that this post-authentic moment is one of evolving, increasingly nuanced collective communication norms, able to operate with multi-layered recursive meanings and ironies in disposable pop culture content… is kind of cold comfort.

Nonetheless, author Robin Sloan described the genius of the “American Chopper” meme as being that “THIS IS THE ONLY MEME FORMAT THAT ACKNOWLEDGES THE EXISTENCE OF COMPETING INFORMATION, AND AS SUCH IT IS THE ONLY FORMAT SUITED TO THE COMPLEXITY OF OUR WORLD!”

May it yet save us.

ETA 21 April: Follow-up note here, on two things this essay misses with regard to the alt-right and race; I hope to flesh this out more fully shortly. Thoughts & further comments are very welcome. I also want to write about “wholesome memes” as a particular current of sincerity. If you’re interested, holler.

Many thanks to Davide Berretta, Rishi Dashidar & Kyle Chayka for pre-reading and editing. This piece is stronger for your feedback. Thank you also to Marc Brenner, who first invited me to pitch this idea for the Market Research Society Social Media Research Summit (Feb 2018).

Consequently this essay also exists as a talk; do get in touch if this is something you or your event, organisation or company might be interested to hear (hautepop@gmail.com). I’m @hautepop on Twitter, too.

In my other life I write about dust.

WRITTEN BY

Jay Owens

I'm interested in complex systems: media, environment, technology. Research Director at pulsarplatform.com.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 1807.25 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1117 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

1 comment:

nice blog.

Post a Comment