A Sense of Doubt blog post #1264 - Why is Python so slow?

Hi readers,

Once again, a straight share because I have fallen behind schedule.

But this is an interesting article for us programmers, especially those who want to use Python for things in which speed is important. Is it app worthy?

Thank you HACKER NOON and ANTHONY SHAW for this excellent analysis of Python speed (or not so much speed).

FROM -

https://hackernoon.com/why-is-python-so-slow-e5074b6fe55b

Group Director of Talent at Dimension Data, father, Christian, Python Software Foundation Fellow, Apache Foundation Member.

Why is Python so slow?

Python is booming in popularity. It is used in DevOps, Data Science, Web Development and Security.

It does not, however, win any medals for speed.

How does Java compare in terms of speed to C or C++ or C# or Python? The answer depends greatly on the type of application you’re running. No benchmark is perfect, but The Computer Language Benchmarks Game is a good starting point.

I’ve been referring to the Computer Language Benchmarks Game for over a decade; compared with other languages like Java, C#, Go, JavaScript, C++, Python is one of the slowest. This includes JIT (C#, Java) and AOT (C, C++) compilers, as well as interpreted languages like JavaScript.

NB: When I say “Python”, I’m talking about the reference implementation of the language, CPython. I will refer to other runtimes in this article.

I want to answer this question: When Python completes a comparable application 2–10x slower than another language, why is it slow and can’t we make it faster?

Here are the top theories:

- “It’s the GIL (Global Interpreter Lock)”

- “It’s because its interpreted and not compiled”

- “It’s because its a dynamically typed language”

Which one of these reasons has the biggest impact on performance?

“It’s the GIL”

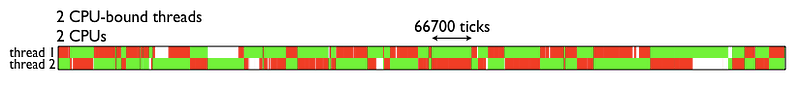

Modern computers come with CPU’s that have multiple cores, and sometimes multiple processors. In order to utilise all this extra processing power, the Operating System defines a low-level structure called a thread, where a process (e.g. Chrome Browser) can spawn multiple threads and have instructions for the system inside. That way if one process is particularly CPU-intensive, that load can be shared across the cores and this effectively makes most applications complete tasks faster.

My Chrome Browser, as I’m writing this article, has 44 threads open. Keep in mind that the structure and API of threading are different between POSIX-based (e.g. Mac OS and Linux) and Windows OS. The operating system also handles the scheduling of threads.

IF you haven’t done multi-threaded programming before, a concept you’ll need to quickly become familiar with locks. Unlike a single-threaded process, you need to ensure that when changing variables in memory, multiple threads don’t try and access/change the same memory address at the same time.

When CPython creates variables, it allocates the memory and then counts how many references to that variable exist, this is a concept known as reference counting. If the number of references is 0, then it frees that piece of memory from the system. This is why creating a “temporary” variable within say, the scope of a for loop, doesn’t blow up the memory consumption of your application.

The challenge then becomes when variables are shared within multiple threads, how CPython locks the reference count. There is a “global interpreter lock” that carefully controls thread execution. The interpreter can only execute one operation at a time, regardless of how many threads it has.

What does this mean to the performance of Python application?

If you have a single-threaded, single interpreter application. It will make no difference to the speed. Removing the GIL would have no impact on the performance of your code.

If you wanted to implement concurrency within a single interpreter (Python process) by using threading, and your threads were IO intensive (e.g. Network IO or Disk IO), you would see the consequences of GIL-contention.

If you have a web-application (e.g. Django) and you’re using WSGI, then each request to your web-app is a separate Python interpreter, so there is only 1 lock per request. Because the Python interpreter is slow to start, some WSGI implementations have a “Daemon Mode” which keep Python process(es) on the go for you.

What about other Python runtimes?

PyPy has a GIL and it is typically >3x faster than CPython.

Jython does not have a GIL because a Python thread in Jython is represented by a Java thread and benefits from the JVM memory-management system.

How does JavaScript do this?

Well, firstly all Javascript engines use mark-and-sweep Garbage Collection. As stated, the primary need for the GIL is CPython’s memory-management algorithm.

JavaScript does not have a GIL, but it’s also single-threaded so it doesn’t require one. JavaScript’s event-loop and Promise/Callback pattern are how asynchronous-programming is achieved in place of concurrency. Python has a similar thing with the asyncio event-loop.

“It’s because its an interpreted language”

I hear this a lot and I find it a gross-simplification of the way CPython actually works. If at a terminal you wrote

python myscript.py then CPython would start a long sequence of reading, lexing, parsing, compiling, interpreting and executing that code.

If you’re interested in how that process works, I’ve written about it before:

An important point in that process is the creation of a

.pyc file, at the compiler stage, the bytecode sequence is written to a file inside __pycache__/on Python 3 or in the same directory in Python 2. This doesn’t just apply to your script, but all of the code you imported, including 3rd party modules.

So most of the time (unless you write code which you only ever run once?), Python is interpreting bytecode and executing it locally. Compare that with Java and C#.NET:

Java compiles to an “Intermediate Language” and the Java Virtual Machine reads the bytecode and just-in-time compiles it to machine code. The .NET CIL is the same, the .NET Common-Language-Runtime, CLR, uses just-in-time compilation to machine code.

So, why is Python so much slower than both Java and C# in the benchmarks if they all use a virtual machine and some sort of Bytecode? Firstly, .NET and Java are JIT-Compiled.

JIT or Just-in-time compilation requires an intermediate language to allow the code to be split into chunks (or frames). Ahead of time (AOT) compilers are designed to ensure that the CPU can understand every line in the code before any interaction takes place.

The JIT itself does not make the execution any faster, because it is still executing the same bytecode sequences. However, JIT enables optimizations to be made at runtime. A good JIT optimizer will see which parts of the application are being executed a lot, call these “hot spots”. It will then make optimizations to those bits of code, by replacing them with more efficient versions.

This means that when your application does the same thing again and again, it can be significantly faster. Also, keep in mind that Java and C# are strongly-typed languages so the optimiser can make many more assumptions about the code.

PyPy has a JIT and as mentioned in the previous section, is significantly faster than CPython. This performance benchmark article goes into more detail —

So why doesn’t CPython use a JIT?

There are downsides to JITs: one of those is startup time. CPython startup time is already comparatively slow, PyPy is 2–3x slower to start than CPython. The Java Virtual Machine is notoriously slow to boot. The .NET CLR gets around this by starting at system-startup, but the developers of the CLR also develop the Operating System on which the CLR runs.

If you have a single Python process running for a long time, with code that can be optimized because it contains “hot spots”, then a JIT makes a lot of sense.

However, CPython is a general-purpose implementation. So if you were developing command-line applications using Python, having to wait for a JIT to start every time the CLI was called would be horribly slow.

CPython has to try and serve as many use cases as possible. There was the possibility of plugging a JIT into CPython but this project has largely stalled.

If you want the benefits of a JIT and you have a workload that suits it, use PyPy.

“It’s because its a dynamically typed language”

In a “Statically-Typed” language, you have to specify the type of a variable when it is declared. Those would include C, C++, Java, C#, Go.

In a dynamically-typed language, there are still the concept of types, but the type of a variable is dynamic.

a = 1 a = "foo"

In this toy-example, Python creates a second variable with the same name and a type of

str and deallocates the memory created for the first instance of a

Statically-typed languages aren’t designed as such to make your life hard, they are designed that way because of the way the CPU operates. If everything eventually needs to equate to a simple binary operation, you have to convert objects and types down to a low-level data structure.

Python does this for you, you just never see it, nor do you need to care.

Not having to declare the type isn’t what makes Python slow, the design of the Python language enables you to make almost anything dynamic. You can replace the methods on objects at runtime, you can monkey-patch low-level system calls to a value declared at runtime. Almost anything is possible.

It’s this design that makes it incredibly hard to optimise Python.

To illustrate my point, I’m going to use a syscall tracing tool that works in Mac OS called Dtrace. CPython distributions do not come with DTrace builtin, so you have to recompile CPython. I’m using 3.6.6 for my demo

wget https://github.com/python/cpython/archive/v3.6.6.zip unzip v3.6.6.zip cd v3.6.6 ./configure --with-dtrace make

Now

python.exe will have Dtrace tracers throughout the code. Paul Ross wrote an awesome Lightning Talk on Dtrace. You can download DTrace starter files for Python to measure function calls, execution time, CPU time, syscalls, all sorts of fun. e.g.sudo dtrace -s toolkit/.d -c ‘../cpython/python.exe script.py’

The

py_callflow tracer shows all the function calls in your application

So, does Python’s dynamic typing make it slow?

- Comparing and converting types is costly, every time a variable is read, written to or referenced the type is checked

- It is hard to optimise a language that is so dynamic. The reason many alternatives to Python are so much faster is that they make compromises to flexibility in the name of performance

- Looking at Cython, which combines C-Static Types and Python to optimise code where the types are known can provide an 84x performance improvement.

Conclusion

Python is primarily slow because of its dynamic nature and versatility. It can be used as a tool for all sorts of problems, where more optimised and faster alternatives are probably available.

There are, however, ways of optimising your Python applications by leveraging async, understanding the profiling tools, and consider using multiple-interpreters.

For applications where startup time is unimportant and the code would benefit a JIT, consider PyPy.

For parts of your code where performance is critical and you have more statically-typed variables, consider using Cython.

Further reading

Jake VDP’s excellent article (although slightly dated) https://jakevdp.github.io/blog/2014/05/09/why-python-is-slow/

Dave Beazley’s talk on the GIL http://www.dabeaz.com/python/GIL.pdf

All about JIT compilers https://hacks.mozilla.org/2017/02/a-crash-course-in-just-in-time-jit-compilers/

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

- Bloggery committed by chris tower - 1808.07 - 10:10

- Days ago = 1130 days ago

- New note - On 1807.06, I ceased daily transmission of my Hey Mom feature after three years of daily conversations. I plan to continue Hey Mom posts at least twice per week but will continue to post the days since ("Days Ago") count on my blog each day. The blog entry numbering in the title has changed to reflect total Sense of Doubt posts since I began the blog on 0705.04, which include Hey Mom posts, Daily Bowie posts, and Sense of Doubt posts. Hey Mom posts will still be numbered sequentially. New Hey Mom posts will use the same format as all the other Hey Mom posts; all other posts will feature this format seen here.

No comments:

Post a Comment